2025_2_Muradyan

Fourteenth-Century Developments in Armenian Grammatical Theory through  Borrowing and Translation: Contexts and Models of Yovhannes K‘ṛnets‘i’s1

Borrowing and Translation: Contexts and Models of Yovhannes K‘ṛnets‘i’s1

Grammar Book

Gohar Muradyan

Mesrop Mashtots Institute of Ancient Manuscripts, Yerevan

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Hungarian Historical Review Volume 14 Issue 2 (2025): 214-246 DOI 10.38145/2025.2.214

The description of Armenian grammar has a long history. Several decades after the invention of the alphabet by Mesrop Mashtots, probably in the second half of the fifth century, Dionysius Thrax’ Ars grammatica was translated from Greek. Until the fourteenth century, eleven commentaries were composed on Thrax’s work. The Ars created the bulk of the Armenian grammatical terminology and artificially ascribed some peculiarities of the Greek language to Armenian. In the 1340s Yovhannēs K‘ṛnets‘i‘i wrote a work entitled On Grammar. He was the head of the Catholic K‘ṛna monastery in Nakhijewan which was founded by Catholic missionaries sent to Eastern Armenia and by their Armenian collaborators, the fratres unitores. K‘ṛnets‘i’s grammar survived in a single manuscript copied in 1350.

In K‘ṛnets‘i’s work, the section on phonetics, the names of the parts of speech and many grammatical categories follow Dionysius’ Ars grammatica. K‘ṛnets‘i also used Latin sources, introducing two sections on syntax, mentioning Priscian, and borrowing definitions from Petrus Helias’ Summa super Priscianum and other commentaries. This resulted in distinguishing substantive and adjective in the section on nouns, in a more realistic characterization of Armenian verbal tenses and voices and the introduction of notions and terms for sentences, their kinds, case government and agreement.

Keywords: Fratres unitores, Yovhannēs K‘ṛnets‘i, Priscianus, Petrus Helias, syntax

What influence did Greek and Latin models exercise on fourteenth-century Armenian grammatical theory? Did Latin models become more authoritative with the arrival of Catholic missionaries in late medieval Armenia? After offering a brief overview of the activities of the fratres unitores, this paper focuses on Yovhannēs K‘ṛnets‘i’s Book on Grammar as a case study which shows how textual imports enriched Armenian grammatical theory and the Armenian language.

Based on the works of Levon Kachikyan and Suren Avagyan, the essay shows that Yovhannēs K‘ṛnets‘i relied on the early Armenian translation of Dionysius Thrax and Dionysius’ commentaries and wrote his section on syntax based on the Latin grammarian Priscianus and also on the works of Priscianus’ commentators. Other scholars, such as Tigran Sirunyan and Peter Cowe, substantialized Avagyan’s and Khachikyan’s speculations on Yovhannēs K‘ṛnets‘i’s Latin sources. Sirunyan in particular showed a series of borrowings from these sources. The paper brings substantial new evidence concerning K‘ṛnets‘i’s reliance on the works of Priscianus and his commentators, namely Petrus Helias. It shows that with the help of Latin grammarians, K‘ṛnets‘i elaborated a more subtle Armenian grammatical theory compared to the Armenian grammatical tradition that had preceded K‘ṛnets‘i, which had been overwhelmingly influenced by Dionysius Thrax’s Greek grammar book.

1 Fratres Unitores: Knowledge Hubs, Cultural Impact, and Translations

In the early fourteenth century, Armenia was under Mongol rule. After proselytising in the Armenian kingdom of Cilicia, Pope John XXII (1316–1334) sent first Franciscan and later Dominican Catholic missionaries to Eastern Armenia. They founded centers for the spread of Catholicism among Armenians in Armenia, such as Artaz and Ernjak (in the Nakhijewan2 province3) and also in neighbouring regions, such as Maragha and the capital of the Mongol Ilkhanate Sult‘aniē in northern Iran and also in Tiflis. The goal of this mission was to convert the Ilkhans of Persia and other khans to Christianity, but these efforts ultimately failed, since the khans embraced Islam and the conditions for Christians deteriorated. The special attitude of Ilkhan Abu Said towards the “Latin friars,” whom he put under his protection in 1320, encouraged local Christians to turn their mind towards the missionaries.4

The Catholic mission was headed by Bartholomew of Podio,5 bishop of Maragha between 1318 and 1330, and his fellow friars, Peter of Aragon and John the Englishman of Swineford.6 Bartholomew was known as an engaging preacher who had gathered around him many young Armenians. Part of the local clergy converted to the new faith. They assisted the missionaries and were called “fratres unitores.”7 They were preceded by the Franciscan Tsortsor monastery founded in the early fourteenth century by Zak‘aria Tsortsorets‘i, aided by Yovhannēs Tsortsorets‘i, vardapet Israyēl, and Fra Pontius.8 The leaders of the Armenian Apostolic Church, in their zeal to preserve its independence, resisted the missionaries and their Armenian adherents and wrote several letters defending the doctrines and rites of the Armenian Apostolic Church.9 Esayi Nch‘ets‘i, the head of the famous Gladzor monastic school, and in particular Nch‘ets‘i’s student Yovhannēs Orotnets‘i and Maghak‘ia Ghrimets‘i in the subsequent generation, as well as Yovhannēs Orotnets‘i’s student, the famous theologian and philosopher Grigor Tat‘ewats‘i (1344–1409), were particularly active in these resistance efforts.10 In the course of this controversy, the pro-Latin faction also produced documents, but few of them have survived.11

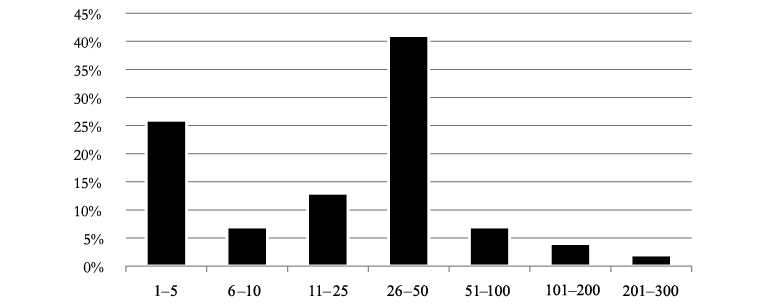

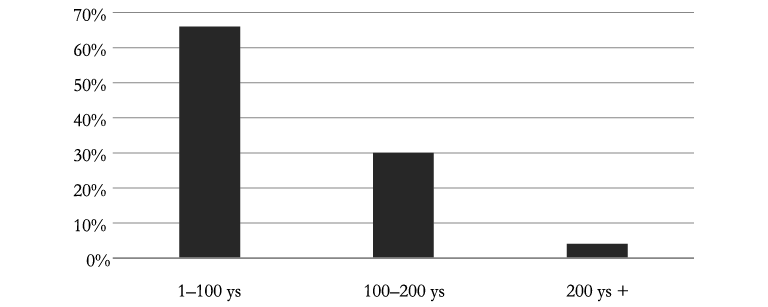

The fratres unitores founded several monastic centers. After his arrival to Maragha in 1318, Bartholomew moved to the monastery of K‘ṛna. This monastery was founded by Yovhannēs K‘ṛnets‘i in 1330 in the village of the same name in the historical Armenian province Nakhijewan.12 After Bartholomew died in 1333, the monastery was led by Yovhannēs K‘ṛnets‘i (until his death in 1347).13 K‘ṛnets‘i cooperated extensively with Yakob K‘ṛnets‘i, Peter of Aragon and John of Swineford (Joannes Anglus14), who made good progress in learning Armenian. The K‘ṛna monastery was named “New Athens” (նոր Աթենք), and it remained active until 1766.15 Another center for the fratres unitores was the St. Nicholas monastery in Kaffa (Crimea).16 As a whole, the congregation consisted of about 14 monasteries at its zenith.17 In 1356, the community of the unitors reached its heyday, running 50 monasteries with about 700 monks. By 1374, the community had declined substantially.18

The fratres unitores translated from Latin Catholic ritual books and Western scholastic authors’ writings, and they also wrote original philosophical, logical, and theological works.19 As a result of their activities, the most important Roman liturgical books became accessible in Armenian.20 Another example, showing the importance of the fratres unitores’ cultural contributions was Bartholomew of Bologna’s On Hexaemeron (Ms M1659, copied in the fourteenth century). It contains considerable information on celestial bodies, plants, and animals based on the writings of several ancient Greek philosophers, medieval theologians, and scholars.21

Most of the translated and original works of the unitor brothers have not yet been published.22 It should be also noted that Marcus van den Oudenrijn’s bibliographic work lists are largely based on the holdings of Western collections.23 At the same time, the largest collection of Armenian manuscripts in Matenadaran (Mesrop Mashtots Institute of Ancient Manuscripts in Yerevan) includes early manuscripts, which contain the bulk of the works listed by Oudenrijn.

The unitors’ intellectual achievements seem to have aroused interest among their adversaries. Although little research has been done on this, it has been stated that the works created in the milieu of the unitors soon reached Armenian intellectual circles, despite the fact that the unitors themselves were trying to ban their spread among their adversaries.24 In a colophon to Bartholomew’s Sermonary, Yakob K‘ṛnets‘i (the most prolific translator of the K‘ṛna school)25 threatens to anathematize and excommunicate anyone who gives it to them.26 In 1363, at the request of Yovhannēs Orotnets‘i, Grigor Tat‘ewats‘i copied Ms M2382 containing Bartholomew’s Dialectics, Gilbertus Porretanus’ Liber sex rerum principiis, and its commentary by Peter of Aragon. In 1389, Yakob Ghrimets‘i, a renowned scholar, copied Ms M3487, a codex encompassing the works of John of Swineford. Yovhannēs Orotnets‘i’s commentaries on Aristotle’s Categories and On Interpretation, on Pophyry’s Isagoge to Aristotle’s Categories and on Philo of Alexandria’s De Providentia witness to his awareness of European methodology applied in philosophical and logical writings.27 It was Grigor Tat‘ewats‘i, the most prominent theologian of the Armenian Church, on whose writings Western philosophy and theology had exerted the strongest influence, and he passes this influence on in his work.28

The language of the texts produced by the unitorian brothers bears Latin influence. This influence resembles the use of the artificial grammatical forms and neologisms in the translations of the so-called Hellenizing school, which was a literary trend in old Armenian literature marked by extreme adherence to the literal translation method and by Greek influence on vocabulary, syntax, and even morphology.29 The tendency to copy Latin words and grammatical features gathered further impetus in the so-called Latinizing (լատինաբան) translations and original works produced in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries by the Catholic preachers, who were alumni of the Collegium Urbanum.30 This collegium was founded in 1627 in Rome and belonged to the Congregation “De propagande fide” founded in 1622 to promote the Catholic faith in eastern Christian countries. Works of the alumni of the Collegium Urbanum included a series of Armenian grammars. Scholars held different views on whether the fourteenth-century and seventeenth- and eighteenth-century texts should be viewed as two separate groups31 of Latinizing Armenian literature or it is one and the same trend which regressed for some time and was revived in the seventeenth century.32

After these introductory remarks on the fratres unitores, I now turn my focus to Yovhannēs K‘ṛnets‘i’s grammatical work.

2.1 Yovhannēs K‘ṛnets‘i and His Grammatical Work: The Circumstances

of its Composition and the Influence of Dionysius Thrax

Yovhannēs K‘ṛnets‘i (ca. 1290–1347) was a student of the abovementioned Esayi Nch‘ets‘i, an outstanding scholar himself and one of the most ardent adversaries of the Catholic faith. In 1328, Esayi sent K‘ṛnets‘i to Maragha to explore the curriculum taught there by Bartholomew of Podio. There, K‘ṛnets‘i adopted Catholicism,33 learned Latin, and taught Armenian to Bartholomew (before learning Armenian, the latter communicated with the Armenian brothers in Persian). In 1330, Yovhannēs K‘ṛnets‘i returned to K‘r. na and persuaded the feudal lord of the village (who was his uncle) and his wife to convert to Catholicism. With their financial aid, K‘ṛnets‘i built a new church on the territory of the local Surb Astuatsatsin (Holy Theotokos) monastery and donated it to the Dominican order. Yovhannēs K‘ṛnets‘i was the head of the K‘r. na monastery between 1333 and 1347. Peter Cowe refers to him as the leading figure among the Armenian scholars who joined the Dominican congregation.34 In 1342, K‘ṛnets‘i traveled to the papal see in Avignon to discuss his future efforts towards the union of the Armenian and Roman Churches.35 One of the colophons of Ms M327636 reads:

In the upper monastery of K‘ṛna, under the protection of the Holy Theotokos, headed by doctor Yovhannēs nicknamed K‘ṛnets‘i, in whose name pious lord Gorg (sic!) and his wife lady Ēlt‘ik founded the holy congregation. And those three, doctor Yohan and Lord Gēorg and lady Ēlt‘ik, willingly donated the monastery to the Order of Preachers of Saint Dominic, an eternal gift. This Yovhannēs caused much benefit; he collected here doctors from Latins and Armenians, taking care of all concerning their soul and body, and he translated and is translating many salutary and enlightening writings… and he brought the redeeming tidings to the Armenian people and led those worthy to the obedience to the high throne of Rome…37

Only one of Yovhannēs K‘ṛnets‘i’s translations survives: Bartholomew’s Liber de inferno, probably translated between 1328 and 1330 in Maragha.38 Alberto Casella summarized information concerning three other translations from Yovhannēs’ quill:39 Bartholomew’s Liber de judiciis, translated in 1328–1330 in Maragha;40 the Regula S. Augustini episcopi de vita religiosorum, translated either by Yovhannēs or by Bartholomew,41 and the Constitutiones ordinis Fratrum Praedicatorum, probably translated by Yovhannēs, from which two lines are cited by Clemens Galanus.42

Marcus Van Oudenrijn contends that another treatise entitled Disputatio de duabus naturis et de una persona in Christo, composed, according to the colophon “by Yovhannēs K‘ṛnets‘i and bishop Bartholomew” (MS M3640, 14th c., 121r–150v), was written by Bartholomew and translated by Yovhannēs.43 In contrast, Arevshatyan claims that they wrote it together in Armenian before Bartholomew moved from Maragha to K‘ṛna.44

As to original works by Yovhannēs K‘ṛnets‘i, his grammatical work and a letter addressed to the fratres unitores have survived. In the letter, Yovhannēs explains his motifs for conversion to the Catholic faith and ascribes 19 “unforgivable errors” to the adherents of the Armenian Apostolic Church.45

Yovhannēs K‘ṛnets‘i probably wrote his Grammar (Յաղագս քերականին)46 in the 1340s. The text has survived in a single manuscript kept in the Mekhitharist congregation in Vienna (Ms W293, 2r–29r).47 It was copied in 1350, three years after the author’s death in Kaffa (Crimea). Marcus van den Oudenrijn, judging by the short information on this text in the catalogue,48 wrote, “Est commentarius in antiquam versionem Artis Grammaticae Dionysii Thracis.”49

However, the colophon at the end reads:

I, fra Yohan K‘ṛna, called by the nickname K‘ṛnets‘i, have made a short compendium from Armenians and Latins, [small] bits from many authors and grammarians, giving a door and a road for the novices to enter the cities of wisdom, to ascend from practice to knowledge, and with this minor art to the art of arts which is the mother and dwelling and abode for those who are directed towards wit and wisdom (as if aroused by a goad and awakened from the vacillation of drowsiness), so that they arrive at the knowledge of the truth and good, which is the perfection of logic.50

K‘ṛnets‘i did indeed write a “short compendium,” and he combined grammatical knowledge from different sources.51 He used the Armenian version of Ars grammatica by Dionysius Thrax,52 translated from Greek in the second half of the fifth century.53 In addition, K‘ṛnets‘i used some of the several commentaries on Dionysius Thrax’s work, which Armenian authors wrote between the sixth and fourteenth centuries, in particular, the commentary written by his teacher in the Gladzor monastery Esayi Nchets‘i.54 Yovhannēs also included information on syntax that he borrowed from Latin grammatical works. Yovhannēs’ work bears some influence of the sections on the noun and verb in Bartholomew’s Dialectics, as has been noticed.55 The grammar book is written in Grabar (Classical Armenian), but some examples are in Middle Armenian (appearing most apparently in the verbal forms with the prepositive particle կու – ku).

Yovhannēs K‘ṛnets‘i applied most of the terms which Dionysius Thrax’ Armenian translator coined, such as the names of the parts of speech and the main grammatical categories. In this respect, K‘ṛnets‘i followed Dionysius’ abovementioned commentators. At the same time, he also created some new terms, especially those about syntax.

In the introduction to the edition of Yovhannēs K‘ṛnets‘i’s grammatical work, Suren Avagyan has pointed out that some parts had been influenced by (sometimes cited from) the work of Dionysius Thax, whom K‘ṛnets‘i mentioned as “the grammarian” (Քերթող, 220).56 Most affected by the Dionysian Grammar are the phonetic sections of the first and longest part, titled “Part One, on the Simple Knowledge,” which contains the following sections: “[1] On the letter,” “[2] On syllables,” “[3] On long syllables,” “[4] On short syllables,” and “[5] On common syllables” (K‘ṛnets‘i also reflects some real features of Classical Armenian,57 in contrast with the Armenian version of Dionysius58). The last short “philological” chapters also show the influence of Dionysius’ Grammar, which are “Part Four, on Prosody,” “Part Five, on Metric Elements,”59 and “Part Six, on Reading.” In the description of the parts of speech (sections 6–14 of “Part One”), K‘ṛnets‘i combines details found in Dionysius’ Grammar and Dionysius’ Armenian commentaries with Latin sources and his observations.

Like Dionysius Thrax, Yovhannēs K‘ṛnets‘i also discussed some grammatical categories which are not characteristic of the Armenian language.60 One of these features is the gender of nouns. He writes: սերք անուանց... արական է իք – այր, իգական է էք – կին, չեզոք է օք – երկին (168, “the gender of nouns… masculine is ik‘ – man, feminine is ēk‘ – woman, neuter is ok‘ – sky”). The strange ik‘, ēk‘, ok‘ forms are transliterations of the Latin pronoun hic, haec, hoc,61 indicating the gender of the related nouns (cf. Petrus 323–327),62 and are called articula (Petrus 326). The same pronoun with various nouns figures in Priscianus’ section “De generibus” (Pr. 141–144).63 Later, Yovhannēs K‘ṛnets‘i cautions that one should “be aware that there is difference of genders… in the Greek and Latin languages, but not in the Armenian speech [where it occurs] just scattered and at random.”64

Yovhannēs K‘ṛnets‘i applied a considerable number of grammatical terms, drawing their origins from Dionysius Thrax’s Ars grammatica, which became common in Armenian grammatical works. The following are the main terms, followed by the corresponding Latin terms in Priscianus’ work65:

անուն (163–72) = Dion. 12–2266 – ὄνoμα (23.1, 24.3, 6, 29.1, 5, 36.1, 5,67 etc.), “nomen;”

թուական (165–6, 198) = Dion. 18.7, 21.22 – ἀριθμετικόν (33.5, 44.4), “numerale;”

բայ (176–81) = Dion. 12.4, 22.11, 15, 24.10, 25.20, etc. – ῥῆμα (23.1, 29.3, 46.4, 53.5, 54.1, 57.5, etc), “verbum;”

ընդունելութիւն (183–6) = Dion. 12.14, 26.23, 24 – μετοχή (23.1, 60.1), “participium;”

մակբայ (181–3) = Dion. 12.16, 31.1, 2, 5 – ἐπίρρημα (23.2, 72.3, 73.1), “adverbium;”

դերանուն (172–6) = Dion. 12.5, 30.1 – ἀντωνυμία (23.2, 63.1), “pronomen;”

նախդիր (189–90), cf. Dion. 12.15, 30.7 նախադրութիւն68 – πρόθεσις (23.2, 70.2), “praepositio;”

յօդ (190–1) = Dion. 12.15, 27.2 – ἄρθρoν (23.2, 66.1), “articulum;”

շաղկապ (186–9) = Dion. 12.6, 35.7, 11 – σύνδεσμoς (23.2, 86.2, 87.1), “conjunctio.”

Among specific terms designating grammatical categories,69 the following are worth mentioning:

սեր մակաւասար … երկբայական (168) – Dion. 13.10 = ἐπίκοινον (25.1), “genus epichenum70 et dubium” (Petrus 325);

գերադրական (167) = Dion. 13.24, 15.12 – ὑπερθετικὸν (25.7, 28.3), “superlativus” (Pr. III.86);

հրամական (177), cf. Dion. 22.21 հրամայական – προστακτική (47.3), “imperativus” (Pr. VIII.406);

ըղձական (177) = Dion. 22.21– εὐκτική (47.3), “optativus” (Pr. VIII.407);

ստորադասական (178) = Dion. 22.21 – ὑποτακτική (47.3), “subjunctivus” (Pr. VIII.408);

բայածական (197) = Dion. 13.25, 16.3 – ῥηματικόν (25.7, 29.3), “verbalium” (Petrus 1026);

աներևոյթ (178) = Dion. 22.20 – ἀπαρέμφατος (47.4), “infinitivus” (Petrus 202).

2.2 The Influence of Priscianus and His Commentators

on Yovhannēs K‘ṛnets‘i Grammar Book: Findings in the Scholarship

The first and last sections of K‘ṛnets‘i’s grammatical work, therefore, are indebted to Dionysius Thrax and his Armenian commentators. In contrast, the second section, titled “Part Two, on the Knowledge of Combination, that is of the Utterance,” and the third section, titled “Part Three, on Syntactic Links,” deal with syntax. These chapters offered something new, since neither the text of Dionysius nor of his commentators had included sections on syntax. The only name Yovhannēs K‘ṛnets‘i mentioned in these parts on syntax71 was Priscianus (Պրիսիանոս) of Caesarea, the sixth-century author of the Institutiones Grammaticae, a systematic Latin grammar. Priscianus’ grammar book became the most influential work during the Middle Ages (especially books XVII and XVIII, the so-called Priscianus minor).

In a recent article, Tigran Sirunyan has demonstrated a considerable number of textual parallels, literal translations, or paraphrases in Yovhannēs K‘ṛnets‘i’s work from Priscianus’ Institutiones grammaticae.72 Sirunyan has also shown that some passages in K‘ṛnets‘i’s grammar can be traced back to Petrus Helias’ Summa super Priscianum (ca. 1150)73 and to Sponcius Provincialis’ commentary on Priscian’s work (from the thirteenth-century).

Sirunyan is convinced that Yovhannēs drew information heavily from Priscianus’ grammar book when describing morphology, though without referring to Priscianus. Sirunyan also contends that in the sections on syntax Yovhannēs relied to Priscianus’ commentator(s). Such remarks as “Priscianus says”74 are borrowed from Priscianus’ commentators.75 For instance, Petrus Helias often used phrases such as “dicit Priscianus” (246), “tractat” (passim, e.g. 258), and “ponit” (passim, e.g. 244). I provide below the main parallels that Sirunyan offered:

Վանկ է պարառութիւն տառից ի ներքո միո ձայնի և միո շնչո անբաժանելի արտաբերեալ (161), “Syllable is a combination of letters pronounced indivisibly in one sound and in one breath” – “Syllaba est comprehensio literarum consequens sub uno accentu et uno spiritu prolata” (Pr. I.44).

The features գոյացութիւն և որակութիւն (164 = “substantia et qualitas,” Pr. I.55) are added to the Dionysian definition of the noun (Dion. 12.22).

Դերանուն է մասն բանի յոլովական, եդեալ փոխանակ յատուկ անուանն և նշանակէ զյատուկ իմն անձն (172), “Pronoun is a declinable part of speech put in the place of a proper noun and shows a certain person”), cf. “Pronomen est pars orationis, quae pro nomine proprio uniuscuiusque accipitur personasque finitas recipit” (Pr., XII.577).

Բայ է մասն բանի հոլովական76, թարց անգման, հանդերձ ամանակաւ և դիմօք, որ նշանակէ ներգործութիւն և կիր կամ զերկոսեանն (176), “Verb is a declinable part of speech, without case, with tense and person, which shows activity and passivity or both”) – “Proprium est verbi actionem sive passionem sive utrumque cum modis et formis et temporibus sine casu significare” (Pr. I.55); “Verbum est pars orationis cum temporibus et modis, sine casu, agendi vel patiendi significativum” (Pr. VIII.369).

Կերպ բային է ձայն, որ ցուցանէ զախորժակ սրտին (177), “Verbal mood is an expression (lit. voice) showing the inclination of the heart” – “Modi sunt diversae inclinationes animi, varios eius affectus demonstrantes” (Pr. VIII.421).

Մակբայ է մասն բանի անհոլովական, որո նշանակութիւնն յաւելեալ լինի բային, որպէս մակադրական անուանքն գոյականացն, քանզի որպէս ասեմք «խոհեմ մարդ», այսպէս և ասեմք, թէ՝ «խոհեմաբար առնէ» (181), “Adverb is an indeclinable part of speech the meaning of which is added to the verb, as the adjectives to the nouns, for as we say ‘prudent man,’ likewise we say ‘he acts prudently’ ” – “Adverbium est pars orationis indeclinabilis, cuius significatio verbis adicitur… quod adjectiva nomina… nominibus, ut ‘prudens homo prudenter agit’ ” (Pr. XV.61).

The following kinds of adverbs correspond to the Latin ones: երդմնական (182) – “jurativa” (Pr. XV.85), ըղձականք (182) – “optativa” (86), կարծողականք (182) – “dubitativa” (86), որպիսականք (182) – “qualitatis” (86), ժամանակականք (182) – “temporales” (81), տեղականք (182) – “locales” (83), հաստատականք (182) – “confirmativa” (85), յորդորականք (182) – “hortativa” (86), քանակականք (182) – “quantitatis” (86), ժողովականք (182) – “congregativa” (87), որոշականք (182) – “discretiva” (87), նմանականք (182) –“similitudinis” (87):

Շաղկապ է մասն բանի անհոլովական, շաղկապական կամ տարալուծական այլոց մասանց բանին՝ ընդ որս նշանակէ կարգաւորեալ զմիտս բանին, ցուցանելով զօրութիւն կամ զկարգ իրաց (186), “Conjunction is an indeclinable part of speech, connective or disjunctive of other parts of speech, with which it manifests the ordered meaning of the utterance, showing the sense (lit. power) or the order of things” – “Conjunctio est pars orationis indeclinabilis, conjunctiva aliarum partium orationis, quibus consignificat, vim vel ordinationem demonstrans” (Pr. XVI.93).

Զօրութիւն, որպէս թէ ասել. «այս անուն էր գթած և խոհեմ» (186), “Sense (lit. power) – as if [one may] say: ‘so-and-so was merciful and prudent’ ” – “vim, quando simul esse res aliquas significant, ut et ‘pius et fortis fuit Aeneas’ ”77 (Pr. XVI.93); զկարգն, յորժամ ցուցանէ զհետևումն իրաց (186, “order, when he shows the sequence of events”) – “ordinem, quando consequentiam aliquarum demonstrat rerum” (Pr. XVI.93).

The following kinds of conjunctions correspond to the Latin ones: բաղհիւսական – “copulativa,” շարադրական – “continuativa” (Pr. XVI.94), ենթաշարադրական – “subcontinuativa,” շարայարադրական – “adjunctiva” (Pr. XVI.95), փաստաբանական (the same in Dion. 36.14 – αἰτιολογικός, 88.1) – “causalis” (Pr. XVI.96), հաստատական – “approbativa” (Pr. XVI.97), տարալուծական – “disjunctiva, ենթատարալուծական – “subdisjunctiva” (Pr. XVI.98), ընտրողական – “electiva,” դիմադրական – “adversativa” (Pr. XVI.99), բաղբանական (= Dion. 37.1 – συλλογιστικός, 88.2) – “collectiva” (Pr. XVI.100), տարակուսական (= Dion. 36.22 – ἀπορρηματικός, 94.2) – “dubitativa” (Pr. XVI.101), թարմատար (187 = Dion. 37.8 –παραπληρωματικός, 96.3) – “completiva” (Pr. XVI.102).

Նախդիր է մասն բանի ոչ հոլովական, որ նախադասի այլոց մասանց բանին յաւելմամբ կամ բաղբանութեամբ (189, “Preposition is an indeclinable part of speech, which is placed before other parts of speech by addition or connection”) – “Est igitur praepositio pars orationis indeclinabilis, quae praeponitur aliis partibus vel appositione vel compositione” (Pr. XIV.24).

Բանն է պատշաճաւոր շարակարգութիւն ասութեանց (191, “Utterance is a suitable order of phrases”) – “Oratio est ordinatio dictionum congrua” (Pr. II.53).

Փրօլեմսիս, սէլէմսիս, սիմթոսիս, զէօմայ, անտիթոզիս (206, transliterated terms: “P‘rolemsis, sēlēmsis simt‘osis, zēōmay, antit‘osis”) – prolemsis et silemsis et zeuma (Petrus 1003), antitosis (Petrus 1005).

Արծիւքն թռեան, այս արևելից, և այն արևմտից (207, “The eagles flew, this one form the east, and that one from the west”) – “Aquilae devolaverunt, haec ab oriente, ille ab occidente” (Pr. XVII.125).

Վերբերականութիւն է նախասացեալ իրին վերստին յիշեցումն (209, “Relation is reminding anew of the thing said before”) – “Relatio est, ut ait Priscianus, antelate rei repetitio” (Sponcius Provincialis).78

Իսկ վերբերականացն ոմն է պակասական և ոմն ոչ պակասական։ Պակասական է՝ «այն, որ կու ընթեռնու», ի յո դնի վերբերականն առանց նախադասութեանց, հիբար՝ «այն, որ կու ընթեռնու, կու տրամաբանէ». զի այն և որն է վերբերական և ոչ ունի նախադասեալ։ Ոչ պակասական է այն, ի յոր դնի վերբերականն և նախադասեալն, հիկէն՝ «մարդն, որ կու ընթեռնու, կու տրամաբանէ»։ Եւ գիտելի է, զի վերբերականս այս՝ «որ», կարէ դնիլ ընդ ամենայն անգմունս իւր, առանց նախադասելոյն (209, “Of relatives some are defective and others non-defective. Defective is: ‘the one who reads’ (in which the relative is put without antecedent,79 as ‘the one who reads, reasons’), since ‘the one’ and ‘who’ is relative and has no antecedent. And not defective is that in which the relative and the antecedent are put, as ‘the man who reads, reasons.’ And it should be known that this relative, ‘who’ may be put in all its cases without antecedent”) – “Relationum alia est ecleptica, et alia non ecleptica. Ecleptica est illa quando relativum ponitur per defectum antecedentis, ut ‘qui legit disputat’. Non ecleptica est, quando relativum et antecedens ponuntur in locutione, ut ‘homo, qui legit, disputat’. Et notandum quod hoc relativum ‘qui’ potest poni per omnes suos casus per defectum antecedentis” (ibid.).

Համրն է, յորժամ մի վերբերական վերաբերի առ միւսն, որպակ «այն, որ կու ընթեռնու, կու տրամաբանէ» (209, “[A relation] is mute80 when one relative relates to another, as: ‘he who reads, reasons’ ”) – “Mutua relatio est illa, quando unum relativum tenetur alteri relativo, ut ‘ille qui legit, disputat’ ” (ibid.).

Անձնական է, յորժամ նախադասեալն և վերբերականն ենթադրին վասն նոյնին, որգոն «մարդ, որ կու ընթեռնու, կու գրէ»։ Պարզ է... յորժամ նախադասեալն ենթադրէ վասն միո և վերբերականն վասն այլո, որգունակ «կինն, որ դատապարտեաց, փրկեաց» (210–211, “[A relation] is personal when the antecedent and the relative are supposed for the same, as ‘the man who reads, writes.’ [A relation] is simple… when the antecedent supposes one and the relative another, as ‘the woman who condemned, saved’.”) – “Personalis relatio est, quando antecedens supponit pro uno appellativo et relativum pro eodem, ut ‘P. legit, qui disputat’. Simplex est, quando antecedens supponit pro uno appellativo et relativum pro alio, ut in theologia ‘mulier quae damnavit, salvavit’81 ” (ibid. 358).

Sirunyan concludes that K‘r. nets‘i is an innovator of Armenian grammatical thought who complemented the Hellenizing Armenian tradition with excerpts from Latin sources.

In addition to Sirunyan, Peter Cowe dedicated an article to K‘ṛnets‘i’s grammar book. Cowe called attention to K‘ṛnets‘i’s reference to the seven liberal arts in the introduction82 and noted that K‘ṛnets‘i had modified the order of his grammatical material compared to Dionysius.

Yovhannēs K‘ṛnets‘i discussed the parts of speech so that the pronoun immediately follows the noun, and the participle follows the verb, and he moved Dionysius’ “philological” chapters from the beginning to the end.83 Cowe also analyzed some aspects of his treatment of the verb (the definition of the verb, the imperative mood, the subjunctive mood) and of the pronoun,84 and he made some remarks on the parts of the book devoted to syntax.85 Cowe mainly collated passages from K‘ṛnets‘i’s text with those of Priscianus. He examined the role of Middle Armenian examples in the grammatical book in question and concluded it with the assertion that its author’s “motive was rather one of enlightened pedagogy to facilitate his pupil’s entry through the door of learning rather than embarking on path of obscurum per obscurius.”86 This means that some of K‘ṛnets‘i’s examples were not taken from the “obscure” literary language but from the living language of his time. Cowe also cited K‘ṛnets‘i’s ideas concerning the grammatical gender peculiar to Greek and Latin and the dual number in Greek and Arabic, which are absent from Armenian. Cowe highlighted K‘ṛnets‘i’s combination of two cases of Armenian under one denomination (see the “sending” case below) and K‘ṛnets‘i’s comments concerning the absence of short and long syllables in Armenian.87

2.3 Further Borrowings from Priscianus and his Commentators

A close reading of K‘ṛnets‘i’s grammar reveals further parallels with the works of Priscianus and Petrus Helias that escaped the attention of the scholars mentioned above. These parallels can be grouped into the following categories.

2.3.1 Terms Created by Yovhannēs by Calquing them from Latin

1. մակդրական (165) – “adjectivum” (Pr. II.60, Petrus 219, 220, 833, 1031)88;

2. գոյացական (165) – “substantivum” (Petrus 766);

3. սեր հաւասար (168) – “genus commune” (Petrus 325);

4. ցուցական դերանուն (173) – “pronomen demonstrativum” (Pr. XII.577, Petrus 629);

5. վերաբերական դերանուն (173) – “pronomen relativum” (Pr. XII.577, Petrus 641)89;

6. ազգական դերանուն (173) – “pronomen gentile” (Petrus 641);

7. ստացական դերանուն (173) = cf. Dion. 29.16–17 – κτητική (68.4) – “pronomen possessivum” (Pr. XII.581, Petrus 629);

8. բայածականք (խնդրեն տրական անգումն… «ինձ գովելի» (197), “verbal [noun]s require the dative case… ‘praiseworthy for me’ ” – “verbalia (… construuntur cum dativo casu... ‘laudabilis’)” (Petrus 1026)90;

9. անցեալ անկատար, անցեալ կատարեալ, անցեալ գերակատար (177), “past imperfect, past perfect, past pluperfect” – “praeteritum imperfectum, praeteritum perfectum, praeteritum plusquamperfectum” (Pr. VIII.405, Petrus 488)91;

10. կերպ բային (177) – “modus verbi” (Pr. VIII.406, Petrus 451)92;

11. սեր բային (176) – “genus verbi” (Petrus 455)93;

12. ցուցական (177) – “indicativus” (Pr. VIII.406, Petrus 523)94;

13. բայք առնողականք (179) – “verbum activum” (Petrus 505), cf. Dion. 22.24 ներգործական = ἐνέργητικός (45.1);

14. անձնական բայք (180) – “personale verbum” (Petrus 874);

15. անանձնական բայք (180) – “impersonale verbum” (Petrus 505);

16. գոյացական բայք (200, 206, 208) – “verbum substantivum” (Pr. VIII.414, Petrus, 1017);

17. կոչնական բայք (200, 208) – “verbum vocativum” (Petrus 507);

18. անգումն (passim) – “casus” (Pr. 57, Petrus passim)95;

19. խնդրել զսեռական / զտրական / զհայցական / զառաքական անգումն (179–180, 195, 197), “to require the genitive/dative/accusative/ ‘sending’ case” – “verba… genetivum exigunt casum” (Pr. 159), “casum exigere” (Petrus passim, e.g. 963, 1055, 1056), the “sending” (առաքական) case was added by the translator of Dionysius after the dative (Dion. 17.18) for the Armenian instrumental case,96 since the Greek dative has such a function. In K‘r. nets‘i’s work, the “sending” case combines the Armenian ablative and instrumental cases, and he offers examples of both (197–198);

20. կառավարել զանգումն (189), “to govern a case,” կառավարութիւն անգմանց (195), “government of cases” – “nomen regit adiectivum… adiectivum regitur a substantivo… substantivum regit adiectivum” (Petrus 1051);

21. կատարեալ շարամանութիւն (198), “perfect construction” – “perfecta constructio” (Pr. XVIII.270, Petrus 648);

22. անկատար բան (198), “imperfect utterance” – “imperfecta oratio” (Pr. XVII.116, Petrus 220);

23. ոչ անցողաբար (199) – “intransitive” (Petrus 874);

24. ձևական շարամանութիւն (206) – “constructio figurativa” (Petrus 902).

2.3.2 Terms Transliterated by Yovhannēs

In addition to փրօլեմսիս, սէլէմսիս, սիմթոսիս, զէօմայ, and անտիթոզիս (examples mentioned above), the following words are also transliterated: “gerundium” (Pr. VIII.410, Petrus 497) – ջերունիդական (178), “supinum” (Pr. VIII.410, Petrus 503) – ջերունդիական (178), “dialecticus” (Petrus 859) – դիալեկտիկոս (193).

2.3.3. Passages More or less Accurately Translated from Latin

1. Հետևին անուանն վեց՝ տեսակք, սերք, թիւք, ձևք, հոլովք, անկումն (164, “Six (accidents) accompany (lit. follow) the noun: species, genders, numbers, forms, declensions, and cases”) – “Accidunt igitur nomini quinque: species, genus, numerus, figura, casus” (Pr. II.57).

2. Մակդրական է, որ յաւելեալ լինի ի վերայ իսկականին (165), “Adjective is what is added to the essential” – “Adiectivum est, quod adicitur propriis…” (Pr. II.60).

3. Գերադրական... Աքիլևս է զօրաւորագոյն ևս յունաց, այսինքն վերադրի քան զամենայն յոյնս (167–8), “Superlative… Achilles is the strongest of Greeks, that is he is put higher than all Greeks” – “Fortissimus Graiorum Achilles… sed superlativus multo alios excellere significat” (Pr. III.86).

4. Հետևին բային ութ, այսինքն՝ սերք, ժամանակ, կերպ, տեսակ, ձևք, լծորդութիւն, դէմք, թիւք (176), “Eight (accidents) accompany (lit. follow) the verb,97 that is voices, tense, mood, species, forms, conjugation, person, numbers”) – “Verbo accidunt octo: significatio sive genus, tempus, modus, species, figura, coniugatio et persona cum numero” (Pr. VIII.369).

5. Արդ սերք բային է որակութիւն իմն կազմեալ ի ձայնական աւարտմանէն և ի բնական նշանակութենէն (176), “Now the voices of the verb are a certain quality fashioned by a word (lit. sound) ending and natural meaning” – “Est igitur genus verbi qualitas verborum contracta ex terminatione et significatione (Petrus 455).

6. Են սերք բային հինգ՝ առնողական, կրողական, չեզոքական, հաւասարական, չեզոքական-կրողական (176), “The voices of the verb are five: active, passive, neutral, common (lit. equal), neutral-passive”) – “Nam cum quinque sint significationes, id est activa, neutra, passiva, communis, deponens” (Pr. XI.564).

7. Չեզոքական է, որոյ գործն նշանակէ առնողական կերպիւ, այլ ոչ անցողական (176), “The neutral [voice] is which signifies action in an active form, but not transitive” – “Neutrum vero genus est qualitas desinendi in o et significandi aliquid quod non sit actio transiens in homines” (Petrus 456).

8. Հաւասարական է, որ միով ձայնիւ նշանակէ զառնելն և զկրելն (176), “The common [voice] is which signifies activity and passivity with the same word” – “Commune vero genus est qualitas desinendi in or et significandi utrumque, scilicet, actionem et passionem” (Petrus 456).

9. Ցուցականք են, որ ցուցանեն զժամանակ, զդէմս և զթիւ (177), “The indicative [verbs] are those which indicate tense, person and number” – “Modi, primus quorum dicitur indicativus, quo, scilicet, indicamus temporum varietatem… vel ab aliis quod fit voces secunde et tercie persone” (Petrus 523–524).

10. Ըղձական կերպ... մակար թէ կու սիրէի (177–8), “Optative mood… would that I loved!” – “Optativus… utinam…” (Pr. VIII.407). The interjection makar in Middle Armenian was borrowed from the late Greek μακάρι.98

11. Տեսակ բայից են երկու՝ նախագաղափար և ածանցական99։ Նախագաղափար, հիզան կարդամ, և ածանցական, որպէս կարդացնեմ, վազեմ-վազեցնեմ, դատեմ-ենթադատեմ (178), “There are two species of the verb: primitive and derivative; primitive, as ‘I read,’ and derivative, as ‘I cause to read,’ ‘I run – I cause to run, I judge – I express’100” – “Species sunt verborum duae, primitiva et derivativa… est igitur primitiva, quae primam positionem ab ipsa natura accepit, ut lego, ferveo…; derivativa, quae a positivis derivantur, ut lecturio, fervesco…” (Pr. VIII.427).

12. Ձևք բային են երեք՝ պարզ, բարդ, յարաբարդ։ Պարզ՝ որկէն եմ, բարդ հիկէն գրեմ, յարաբարդ որբար սրբագրեմ (178), “There are three forms of the verb: simple, compound and super-compound. Simple, as ‘I am,’ compound, as ‘I write,’ super-compound, as ‘I correct (lit. write clean)’101” – “Figura quoque accidit verbo, quomodo nomini. Alia enim verborum sunt simplicia, ut cupio, taceo, alia composita, ut concupio, conticeo, alia decomposita, id est a compositis derivata, ut concupisco, conticesco” (Pr. VIII.434).

13. Առաջին [դէմք] որ խօսի, երկրորդ է, ընդ որում խօսի, երրորդ է, յորմէ խօսի (179), “The first person is the one who speaks, the second is to whom one speaks, the third is of whom one speaks” – “Prima persona praeponitur aliis, quia ipsa loquitur et per eam ostenditur et secunda, ad quam loquitur, et tertia, de qua loquitur” (Pr. VIII.423).

14. Բայք ոմանք անկանոնք (179), “Some verbs are irregular.” An example of a suppletive verb is offered: կու ուտեմ, “I eat” (Middle Armenian present form), կերա “I ate” – “Irregularium vel inequalium declinatio” (Petrus 514, with the example “fero… tuli”).

15. Ընդունելութիւն է մասն բանի հոլովական, որ լինի առեալ փոխանակ բայի, ուստի և ածանցի իսկ, ունելով սերք և անգումն ըստ օրինակի անուան, զժամանակս և զնշանակութիւնս ի բայէն (183), “Participle is a declinable part of speech, which is taken instead of the verb, from which it derives, having gender and case like the noun, tense and significance102 from the verb” – “Participium est igitur pars orationis, quae pro verbo accipitur, ex quo et derivatur naturaliter, genus et casum habens ad similitudinem nominis et accidentia verbo absque discretione personarum et modorum... accidunt autem participio sex: genus, casus, significatio, tempus, numerus, figura” (Pr. XI.552).

16. Ասէ Պրիսիանոս, թէ ոչինչ բան է կատարեալ թարց բայի (191), “Priscianus says that no utterance is complete without a verb” – “Primo loco nomen, secundo verbum posuerunt, quippe cum nulla oratio sine iis completur” (Pr. XVII.116).

17. Գոյացականքն և մակադրականքն պարտին համաձայնիլ103 ի յերիս պատահմունս, այսինքն ի սերս, ի թիւս և ի յանկմունս (192), “Substantives and adjectives must agree in three accidents, that is in gender, in number and in case” – “Dicuntur accidentia nomini casus et numerus” (Petrus 211).

18. Շարամանութիւն է յարմար շարակարգութիւն ասութեանց (198), “Construction is the fitting arrangement of phrases” – “Constructio itaque est congrua dictionum ordinatio” (Petrus 832).

19. Ի կատարեալ շարամանութեանց ոմն է անցողական և ոմն ոչ անցողական, և ոմն անդրայշրջական (199), “Of complete constructions, one is transitive, one intransitive, and one reciprocal” – “Constructionum autem alia transitiva, alia intransitiva, alia recirpoca” (Petrus 897).

20. Արդ անցողական շարամանութիւն է, ի յոր առնումն և կրումն բանին անցանէ ի մի դիմէն ի միւսն, հիպէս «Պետրոս ընթեռնու զԵսային» (199), “Now transitive construction is [that] in which the activity and passivity of the utterance passes from one person to another, as ‘Peter reads Isaiah’ ” – “Transitiva vero constructio est quando fit transitus de una persona in aliam, ut ‘Socrates legit Vergilium’ ” (Petrus 898).

21. Ոչ անցողական շարամանութիւն է, որ առնումն և կրումն ոչ անցանի ի մի դիմէն ի միւսն, որզան «Սոկրատէս ընթեռնու» (199), “Intransitive construction is [that] in which the activity and passivity does not pass from one person to another, as ‘Socrates reads’ ” – Intransitiva constructio est in qua non fit transitus de una persona in aliam, ut ‘Priscianus legit’ (Petrus 898).

22. Իսկ անդրանցական շարամանութիւն է այն, ի յոր նոյն անձն ցուցանէ առնել և կրել, հիզան «ես կու սիրեմ զիս, դու կու սիրես զքեզ, նա կու սիրէ զինքն» (199), “While reciprocal construction is in which the same person shows activity and passivity, as ‘I love myself, you love yourself, he loves himself’ ” – “Reciproca vero constructio est in qua ostenditur aliqua res in se ipsam agere, ut ‘Socrates diligit se’ ” (Petrus 899).

23. Բաղադրեալ բանիցն մին մասն կոչի նախընթաց, և միւսն հետևեալ (199, “One part of compound utterances is called antecedent, the other consequent”) – “Relatio quandoque fit ad antecedens, quandoque ad consequens” (Petrus 910).

24. Բայք կոչնականք... ես կու կոչիմ արդար (200), “Vocative verbs… I am called just” – “Vocativa, ut Priscianus: vocor, nominor, nuncupor, appellor” (Pr. VIII.144).

25. Սիլեմսիս է զանազան ասութեանց միով բայիւ համազոյգ յղութիւն (207), “The syllempsis is a collecting of different phrases united with one verb” – “Silemsis vero est diversarum clausularum per unum verbum conglutinata conceptio” (Petrus 1004). Here յղութիւն, “conception, pregnancy,” is used as a semantic calque of “conceptio” in the sense of “grasp, collecting.”

26. Առաջին դէմն յղանա զառաջին և զերկրորդ դէմն, հիպէս «ես և դու և նա ընթեռնումք»… երկրորդ դէմն յղանա զերրորդ դէմն ներքո բայի երկրորդ դիմացն, որ այսպէս. «դու և նա ընթեռնոյք» (207), “The first person collects (lit. conceives) the first and the second and the third person, as ‘I and you and he [we] read’... the second person collects (lit. conceives) the third person under the verb in second person, as ‘you and he [you] read’ ” – “Concipit autem prima persona secundam et terciam... Prima concipit secundam ut ‘Ego et tu legimus’… prima persona concipit terciam ut ‘Ego et ille legimus’… ‘Tu et ille legitis’. Potest enim secunda persona concipere terciam” (Petrus 998).

These passages listed above are the moments in K‘r. nets‘i’s grammatical work that I could trace to Priscianus’ and Petrus Helias’ grammatical works. Based on these passages, I can make the following observations:

a) All the 24 grammatical terms (2.3.1) calqued by Yovhannēs from Priscianus are also found in Petrus Helias’ text. As far as the phrases translated from Latin are concerned, the origins of twelve of them are found in Priscianus and 14 in Petrus Helias. So K‘ṛnets‘i’s dependence on Petrus Helias is stronger than had been previously noticed, but this does not mean that he used Priscianus through the mediation of Petrus, as Levon Khachikyan has argued.104

Taking into consideration the parallels with Sponcius Provincialis (section 2.2), one can assume that Yovhannēs drew information from various sources, as he himself writes in his colophon cited above: “from Armenians and Latins, [small] bits from many authors and grammarians.”105 Bartholomew of Podio could have brought a book from Italy containing excerpts from Priscianus and other grammarians, and Yovhannēs could have used it as a source.

b) K‘ṛnets‘i’s dependence on Latin sources is more extensive than noted by previous scholarship. The influence of Latin grammarians promoted Armenian grammatical theory to a more advanced stage in comparison to the Dionysian tradition. K‘ṛnets‘i covered more aspects of the language and drew a more realistic picture of Classical Armenian, while also reflecting some elements of Middle Armenian. K‘ṛnets‘i singled out substantives and adjectives from the general notion of “noun” (2.3.1.1–2), introduced the categories of transitive and intransitive verbs (2.3.1.12–13), irregular verbs (2.3.3.14), case government (2.3.1.19–20) and agreement (2.3.3.17), of complex sentences (2.3.3.23), the notion that the participle shares features both with the noun and the verb (2.3.3.15), and the explanation of the three persons of the verb (2.3.3.13).

c) Some grammatical terms used by K‘ṛnets‘i are still in use today and are common in the modern Armenian grammatical works.106 To give examples, the terms for “verbal nouns”107 (2.3.1.8), “past imperfect” and “past perfect” (2.3.1.9), verbal “modes” (2.3.11.10) and “voices” (2.3.1.11), the “neutral voice” (2.3.3.6–7), “derivative verbs” (containing prefixes and suffixes – 2.3.3.11), “irregular verbs” (2.3.3.14) go back to K‘r. nets‘i’s grammar book.

3. The Afterlife of Yovhannēs K‘ṛnets‘i’s Grammatical Work

For a long time, Yovhannēs K‘ṛnets‘i’s grammatical work remained inside the milieu of Armenian unitors and was unknown to wider learned circles. This explains why later grammarians, such as Ar. ak‘el Siwnets‘i in the first quarter of the fifteenth century and Dawit‘ Zeyt‘unts‘i in late sixteenth century were not aware of K‘ṛnets‘i’s work and wrote new commentaries on the grammar book of Dionysius Thrax. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, many grammatical works appeared that show acquaintance with K‘ṛnets‘i’s work.108 Avagyan contends that Priscianus’ work and its commentaries were K‘ṛnets‘i’s sources, especially regarding questions of syntax. In this respect, K‘r. nets‘i’s grammar is close to several so-called “Grecizing-Latinizing grammars” (հունա-լատինատիպ) written in the eighteenth century.109 Avagyan mentions K‘ṛnets‘i’s influence on the description of nominal and pronominal declensions, the semantic categories of pronouns and the detailed conception of the verbal voices and the Middle Armenian passive suffix ui (ուի/վի). Avagyan has also singled out K‘ṛnets‘i’s influence, to name but a few, on the conjugations of the verb, the more detailed characterization of the participle, the conception of verbs governing certain cases, and other syntactic features.110 The recurrence of K‘ṛnets‘i’s views on grammar in the eighteenth century is a research topic which could be fruitfully studied in the future.

Conclusion

The Armenian Catholic convert Yovhannēs K‘ṛnets‘i, head of the unitorian K‘ṛna monastery in Nakhijewan between 1333 and 1347, became an active agent of the monastery’s cultural activity. He wrote a work On Grammar probably in the 1340s. It partly continues the Armenian grammatical tradition which originated in the late fifth century with the translation of Dionysius Thrax’s Art of Grammar from Greek and also shows the influence of the Latin tradition. As has been illustrated with new evidence, K‘ṛnets‘i’s grammar shows numerous verbal parallels with Priscian’s sixth-century Institutiones grammaticae and Petrus Helias’ twelfth-century commentary Summa super Priscianum on Priscian’s work. The main bulk of new terms and concepts, as well as whole definitions, goes back to these sources. A comparison with other Latin sources might reveal more parallels. Compared to the Armenian version of Dionysius Thrax and its Armenian commentaries, K‘ṛnets‘i’s grammar book shows more “real” features of the Armenian language, i.e. categories that were not artificially borrowed from Greek and were non-existent in Armenian. The most important novelty of K‘ṛnets‘i’s grammar is the sections on syntax. Yovhannēs K‘ṛnets‘i’s grammatical work exerted a considerable influence on several grammars of Latinizing Armenian composed in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Adonts‘, Nikolaos. Дионисий Фракийский и армянские толкователи [Dionysius the Thrax and his Armenian commentators]. Petrograd: Imperial Academy of Sciences Press, 1915. = Idem, Երկեր հինգ հատորով Գ` Հայերենագիտական ուսումնասիրություններ [Works in five volumes. vol. 3, Armenological Studies). Yerevan: Yerevan State University Press, 2008, ix–clxxxiii, 1–305 (the Armenian translation of the study by Olga Vardazaryan and the reproduction of the texts).

Alpi, Federico. “Il dibattito sul primato di Pietro in Armenia fra XIV e XV secolo: la testimonianza del «Girk‘ Ułłap‘ar. ac‘» di Mxit‘arič‘ Aparanec‘i.” Cristianesimo nella storia 41 (2020): 43–137.

Bartholomew of Bologna. «Յաղագս հնգից ընդհանրից» (“De quinque communibus vocibus”). In Arevshatyan, Sen. Բարդուղիմեոս Բոլոնիացու հայկական ժառանգությունը (The Armenian Legacy of Bartholomew of Bologna), 75–106. Yerevan: “Limuš SPЭ” Press, 2014.

Clemens Galanus. Conciliationis ecclesiae Armenae cum Romana prima pars historialis. Rome: Typis Sacrae Congregationis de Propaganda Fide, 1650.

Dionysius Thrax. Ars grammatica. Edited by Gustav Uhlig. Leipzig: Teubner, 1965.

Ioannes Agop sacerdos Armenus. Puritas linguae Armenicae. Rome: Ex Typographia Sacrae Congregationis de Propaganda Fide, 1674.

Ioannes Agop sacerdos Armenus. Puritas Haigica seu Grammatica Armenica. Rome: Typis Sacrae Congregationis de Propaganda Fide, 1675.

Ioannes Agop sacerdos Armenus Constantipolitanus. Grammatica Latina. Rome: Typis Sacrae Congregationis de Propaganda Fide, 1675.

Petrus Helias. Summa super Priscianum. Edited by Leo Relly. Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Medieval Studies, 1993.

Prisciani Institutionum Grammaticarum libri I–XII. Eduited by Henrich Keil. Leipzig: Teubner, 1855.

Prisciani Institutionum Grammaticarum libri XIII–XVIII. Edited by Heinrich Keil. Leipzig: Teubner, 1859.

Thurot, Charles. Extraits des divers manuscrits Latins pour server a l’histoire des doctrines grammaticales au moyen age. Paris: imprimerie impériale, 1869.

Yovhannes K‘ṛnets‘i. Յաղագս քերականին [On grammar]. Edited by Levon Khachikyan, introduction by L. Khachikyan (3–51, historical sketch), and Suren Avagyan (52–153). Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences Press, 1977.

Secondary Literature

Abeghyan, Manuk. Երկեր [Works]. Vol. IV, Հայոց հին գրականության պատմություն, երկրորդ շրջան [History of old Armenian literature, second period]. Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences Press, 1970.

Achaṛyan, Hrach‘ya. Հայոց լեզվի պատմություն [History of Armenian language]. Vol. 2. Yerevan: Haypethrat, 1951.

Anasyan, Hakob. Հայկական մատենագիտություն, V–XVII դդ. [Armenian bibliography, V–XVII cc.]. Vols. 1–2. Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences Press, 1950, 1976.

Arevshatyan, Sen. “Գրիգոր Տաթևացին և նրա «Հարցմանց գիրքը» [Grigor Tat‘ewats‘i and his Book of Questions]. In Grigor Tat‘ewats‘i, Գիրք հարցմանց [Book of questions]. Jerusalem: St. James Press, 1993, I–XII.

Calzolari, Valentina. “L’école hellenisante. Les circonstances.” In Ages et usages de la langue arménienne, edited by Marc Nichanian, 110–30. Paris: Editions Entente, 1989.

Calzolari, Valentina. “Les traductions Arméniennes de l’École hellénizante et l’intorduction des arts du trivium en Arménie.” In Les arts libéraux et les sciences dans l’Arménie ancienne et médiévale, edited by Valentina Calzolari, 19–52. Paris: Vrin, 2022.

Casella, Alberto. Bartolomeo de Podio (da Bologna) e la Scuola teologica tomista dei “Fratres Unitores” in Armenia. Armenia tra il XIV e il XV secolo. Un caso di interculturazione. Bologna: Edizioni Studio Domenicano, 2024.

Cowe, Peter. “The Role of Priscian’s Institutiones Grammaticae in Informing Yovhannēs K‘r. nec‘i’s Innovative Account of Armenian Grammar with regard to Terminology, Classification, and Organization with Special Focus on his Investigation of Syntax.” Revue des études arméniennes 39 (2020): 91–121. doi: 10.2143/REA.39.0.3288967

Ghazaryan, Ruben, Avetisyan, Henrik. Միջին հայերենի բառարան [Dictionary of Middle Armenian]. Yerevan, 2009.

Khаch‘ikyan, Levon. “Արտազի հայկական իշխանությունը և Ծործորի դպրոցը” [The Armenian Princedom of Artaz and the School of Tsortsor]. Բանբեր Մատենադարանի [Bulletin of Matenadaran] 11 (1973): 125–210. Reprint in Khаch‘ikyan, Levon, Works, vol. 2, 51–156. Yerevan: Nairi, 2107. References are given to this edition.

Khachikyan, Levon. Քռնայի հոգևոր-մշակութային կենտրոնը և Հովհաննես Քռնեցու գիտական գործունեությունը [The religious and cultural center of K‘ṛna and the scholarly activities of Yovhannēs K‘ṛnets‘i]. Introduction to Yovhannēs K‘r. nets‘i, Յաղագս քերականին [On the grammar]. Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences, 1977 (reprint in Khachikyan, Levon. Works, vol. 2, 449–83.Yerevan: Nairi, 2017).

Khachikyan, Levon, Artashes Matevosyan, Arpenik Ghazarosyan. Հայերեն ձեռագրերի հիշատակարաններ, ԺԴ դար, Մասն Բ, 1326–1350 թթ. [Colophons of Armenian manuscripts, XIV century. Part two, 1326–1350]. Yerevan: Matenadaran, 2020.

Hambardzumyan, Vazgen. Լատինաբան հայերենի պատմություն [History of Latinizing Armenian]. Yerevan: Nairi, 2010.

J̌ ahukyan, Gevorg. Քերականական և ուղղագրական աշխատությունները միջնադարյան Հայաստանում [Grammatical and orthographical works in ancient and medieval Armenia]. Yerevan: Armenian State University, 1954.

J̌ ahukyan, Gevorg. Գրաբարի քերականության պատմություն [History of the grammar of ancient Armenian]. Erevan: Armenian State University Press, 1974.

Kneepkens, Onno C. H. “‘Mulier qui damnavit, salvavit’. A Note on the Early Development of Relatio Simplex.” Vivarium 14, no. 1 (1976): 1–25.

La Porta, Sergio. “Armeno-Latin Intellectual Exchange in the Fourteenth Century: Scholarly Traditions in Conversation and Competition.” Medieval Encounters 21 (2015): 269–94.

Minasyan, “Yovhannēs Orotnets‘i, Life and Works.” Bulletin of Yerevan University. Armenian Studies 17, no. 2 (2015): 3–19.

Muradyan, Arusyak. Հունաբան դպրոցը և նրա դերը հայ քերականական տերմինաբանության ստեղծման գործոմ [The Hellenizing school and its role in the creation of the Armenian grammatical terminology). Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences Press, 1971.

Muradyan, Gohar. “The Reflection of Foreign Proper Names, Theonyms and Mythological Creatures in the Ancient Armenian Translations from Greek.” Revue des Études Arméniennes 25 (1994–1995): 63–76.

Muradyan, Gohar. Grecisms in Ancient Armenian, Leuven–Paris–Dudley, MA: Peeters, 2012.

Muradyan, Gohar, Topchyan, Aram. “The Anonymous Armenian Commentaries on Aristotle’s Categories and on Interpretation. Translations or Original Works?” Le Muséon 137, no. 3–4 (2024): 435–47.

Oudenrijn, Marcus Antonius van den. Linguae haicanae scriptores ordinis praedicationis fratrum unitorum eff. armenorum ord. S. Basilii citra mare consistentium quotquot huc usque innotuerunt. Bern: A. Francke Ag. Verlag, 1960.

Oudenrijn, Marcus Antonius van den. “L’Etude de la philosophie dans le couvent de K‘ṛna.” Bazmavep, Revue d’étude arméniennes 140 (1982): 53–67.

Seidler, Martin. Römische Liturgien in Armenischen Ordensgemeinschaften. Münster: LIT Verlag, 2022.

Seidler, Martin. “Medieval Armenian Congregations in Union with Rome.” In Monastic Life in the Armenian Church: Glorious Past. Ecumenical Reconsideration, edited by Jasmin Dum Tragut, and Dietmar Winkler, 148–57. Münster: LIT Verlag, 2019.

Sophocles, Evangelinus Apostolides. Greek Lexicon of Roman and Byzantine Periods. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1900.

Sirunyan, Tigran. “Հովհաննես Քռնեցու քերականական երկի սահմանումների լատիներեն նախօրինակները” [The Latin archetypes of the definitions in the grammatical work by Yovhannēs K‘ṛnets‘i]. Բանբեր Մատենադարանի [Bulletin of Matenadaran] 24 (2017): 122–40.

Stopka, Krzysztof. Armenia Christiana: Armenian Religious Identity and the Churches of Constantinople and Rome (4th–15th Centuries). Krakow: Jagiellonian University Press, 2017.

Tashean (Dashian), P. Jakobus. Catalog der Armenischen Handschriften in der Mechitharisten-Bibliothek zu Wien. Vienna: Mechitharisten Buch, 1895.

Ter-Vardanyan, Gevorg. “Ունիթորություն” (The Unitorian movement). In Քրիստոնյա Հայաստան հանրագիտարան [Encyclopaedia Christian Armenia], 1038–1039. Yerevan: Editorial board of the Armenian Encyclopaedia, 2002.

Tinti, Irene. “Problematizing the Greek Influence on Armenian Texts.” Rhesis, International Journal of Linguistics, Philology and Literature 7, no. 1 (2016): 28–43. doi: 10.13125/rhesis/5592

Tsaghikyan, Diana. “From the History of Catholic Preaching in Armenia in the 14th Century with Special Reference to Yovhannēs Krnetsi.” In Etchmiadzin (2022): Appendix, 45–61. doi: 10.56737/2953-7843-2022.13-45

Zarphanalean, Garegin. Պատմութիւն հայերէն դպրութեանց [History of Armenian literature]. Vol. 2, Նոր մատենագրություն [Modern literature]. Venice: Mxit‘arean, 1878.

Weitenberg, Jos. “Hellenophile Syntactic Elements in Armenian Texts.” In Actes du Sixième Colloque international de Linguistique arménienne: INALCO, Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres, 5–9 juillet 1999 (Slovo 26–27, 2001–2002), edited by Anaid Donabédian, Agnès Ouzounian, 64–72. Paris: INALCO, 2003.

Weitenberg, Jos. “Greek Influence in Early Armenian Linguistics.” In History of the Language Sciences: An International Handbook on the Evolution of the Study of Language from the Beginnings to the Present, edited by Sylvain Auroix et al., vol. 1, 447–50. Berlin–New York: Walter de Gruyter, 2000.

APPENDIX

Works and Translations by the fratres unitores: Published Texts

1. Ritual Books

Պրէվիար որ է ժամագիրք սրբազան կարգին Եղբարց Քարոզողաց [Breviarium sacri ordinis ff. praedicatorum]. Venice: Antonio Bortoli, 1714.

Ժամագիրք սրբուհւոյ կուսին Մարիամու Աստուածածնին [Officium sanctae virginis Mariae]. Venice: Antonio Bortoli, 1706.

Van Den Oudenrijn Marcus Antonius, ed. Կանոն սրբոյ Դօմինիկոսի խոսփովանոդին [Das Offizium des heiligen Dominicus des Bekenners im Brevier des “Fratres Unitores” von Ostarmenien. Ein Beitrag zur Missions und Liturgiegeschichte desvierzehnten]. Rome: Institutum Historicum FF. Praedicatorum, 1935.

2. Canon Law

Oudenrijn, Marcus Antonius van den, ed. Les Constitutions des Frères Arméniens de S. Basile en Italie. Rome: Instituto Orientale, 1940.

3. Works by Thomas Aquinas

Oudenrijn, Marcus Antonius van den, ed. Eine alte armenische Übersetzung der Tertia Pars der Theologischen Summa des Hl. Thomas von Aquin: Einleitung nebst Textproben aus den Hss Paris Bibl. Naz. Arm. Bern: A. Francke Ag. Verlag, 1955.

Oudenrijn, Marcus Antonius van den, ed., John of Swineford, compiler. Der Traktat Jalags arakinoutheanc hogiojn. Von den Tugenden der Seele: ein armenisches Exzerpt aus der Prima Secundae der Summa Theologica des Hlg. Thomas von Aquin. Fribourg: Librairie de I’Universite, 1942.

Oudenrijn, Marcus Antonius van den. “La version arménienne du supplementum ad tertiam partem Summae Theologicae.” Angelicum 10, no. 1 (1933): 3–23.

Oudenrijn, Marcus Antonius van den. “Traductions arménienne du la Somme Théologique.” Mekhitar, numéro special de la Revue arménienne Pazmaveb (1949): 313–55.

4. A Work Attributed to Albert the Great

Համառօտութիւն աստուածաբանութեան Մեծին Ալպերտի [Compendium theologiae Alberti Magni]. Venice: Antonio Bortoli, 1715.111

Oudenrijn, Marcus Antonius van den. “Un florilège arménien de sentences attribuées à Albert le Grand.” Orientalia 7 (1938): 118–26.

5. Works by Peter of Aragon

Վասն եւթն մահու չափ մեղացն [De septem peccatibus mortalibus]. In Bartholomew and Peter, Խրատականք և հոգեշահք քարոզք [Instructive and salutary sermons]. Venice: publisher not indicated, 1704, 142–270.

Գիրք առաքինութեանց [Liber de virtutibus]. In Peter of Aragon, Book of Virtues, 1–643. Venice: Demetrios T‘eodoseants‘, 1772.

Յաղագս ութից երանութեանց [De octo beatudinibus]. In Peter of Aragon, Book of Virtues, 644–714. Venice: Demetrios T‘eodoseants‘, 1772.

Գիրք մոլութեանց [De vitiis]. In Peter of Aragon, Book of Vices, 1–456. Venice: Demetrios T‘eodoseants‘, 1773.

Յաղագս պահպանութեան հինգ զգայութեանց [De quinque sensum custodia]. In Peter of Aragon, Book of Vices, 457–66. Venice: Demetrios T‘eodoseants‘, 1773.

Յաղագս պահպանման լեզուի [De custodia linguae]. In Peter of Aragon, Book of Vices, 467–73. Venice: Demetrios T‘eodoseants‘, 1773.

Հաւաքումն յաղագս տասն պատուիրանացն [Compilatio de decem praeceptis]. In Peter of Aragon, Book of Vices, 474–518. Venice: Demeter T‘eodoseants‘, 1773.

6. Works by Bartholomew of Podio

Յաղագս հնգից ընդհանրից [De quinque communibus vocibus]. In Arevshatyan, The Armenian Legacy of Bartholomew of Bologna, 73–110.

Sermons on Confession. In Խրատականք և հոգեշահք քարոզք [Instructive and salutary sermons]. Venice: publisher not indicated, 1704, 9–141.

Bartholomew of Bologna, Dialectica, critical text by Tigran Sirunyan (forthcoming).

-

1 The transliteration of Armenian names follows the Library of Congress Armenian Romanization Table (https://www.loc.gov/catdir/cpso/romanization/armenian.pdf, last accessed Jan 10, 2025). The Mss I refer to from the collection of Matenadaran (Mesrop Mashtots Institute of Ancient Manuscripts in Yerevan) start with M followed by shelf numbers. The numbers of Armenian manuscripts in the collections of the congregation of Mekhitharists are preceded by the acronyms V (Venice, San Lazzaro) and W (Vienna). The acronym J represents the collection in the Saint James monastery in Jerusalem.

-

2 In 1921, this Armenian province was annexed to Azerbaijan.

-

3 The majority of the inhabitants of several villages in this province adopted the Catholic faith, Khachikyan, “The Armenian Princedom of Artaz,” 83, footnote 2.

-

4 Stopka, Armenia Christiana, 205–6.

-

5 In the fifteenth century, he also began to be referred to as Bartholomew of Bologna or Parvus as a result of a confusion with his namesake, see Casella, Bartolomeo de Podio (da Bologna), 75, n. 3. In Armenian manuscripts he figures as “bishop of Maragha” (Ms M3372, copied in 1761, fol. 356r), “Frank bishop” (M2515, copied in 1323, fol. 82r), “Frank bishop of Maragha” (Ms W312, copied in 1329, fol. 13r), “Latin bishop” (Ms J815, copied in 1325), “saint bishop Lord Bartholomew” (Ms V12, copied in 1332, fol. 188r). Frank/Fr. ank is the denomination of Westerners, especially Catholic French and Italians. In Armenian scholarly literature, he is usually called Bartholomew of Maragha.

-

6 Joannes Anglus, according to Oudenrijn, Linguae haicanae scriptores, 24, 194, 195.

-

7 Khachikyan, Introduction to Yovhannēs K‘ṛnets‘i On Grammar, 16–51.

-

8 Khachikyan, “The Armenian Princedom of Artaz,” 204–7.

-

9 Tsaghikyan, “Catholic Preaching in Armenia,” 51–53.

-

10 La Porta, “Armeno-Latin Intellectual Exchange in the Fourteenth Century,” 274, 285–93.

-

11 Chapter 33 of one of such documents, the Գիրք ուղղափառաց (Libro dei Ortodossi) by Mkhit‘ar Aperanec‘i written in 1410, was recently published, with a study and Italian translation, see Alpi, “Il dibattito.”

-

12 Bartholomew’s activity in Maragha, including the founding of the school of K‘ṛna and the related events, are known from the work of an unitorian author Mkhit‘ar Aperanec‘i, Oudenrijn, Linguae haicanae scriptores, 216–28.

-

13 On his life, see Tsaghikyan, “Catholic Preaching in Armenia,” 53–57.

-

14 Oudenrijn, Linguae haicanae scriptores, 195.

-

15 Zarphanalean, History of Armenian Literature, 194–212: «Միաբանասիրաց դպրոց» (The School of the Union Supporters); Abeghyan, Երկեր (Works), vol. IV, 403–4: «Ունիթոռական գրականություն և լատինաբան աղճատ հայերեն» (The Literature of the Unitors and the Distorted Latinizing Armenian); Ter-Vardanyan, «Ունիթորություն» (The Unitorian Movement); Oudenrijn, Linguae haicanae scriptores. This book contains a brief history of the fratres unitores (19–72) and a comprehensive bibliography (mentioning editions and manuscripts) of their literary production: Armenian-Dominican sacred books (73–122), sermons and sermonaries (123–72), theological writings (173–244), and “De fratribus armenis citra Mare consistentibus” (245–95). A bibliography (manuscripts and editions) of writings by Albert the Great and Bartholomew of Bologna can be found in Anasyan, Armenian Bibliography, 5th-17th cc., vol. 1, 388–402, vol. 2, 1284–1320.

-

16 Seidler, “Medieval Armenian Congregations in Union with Rome,” 153. A considerable Armenian population lived in Kaffa, which was under Genoese rule at the time. For this reason, the unitores not only built monasteries in Armenia and Georgia but also crossed the Black Sea and founded a public university (“universale studiorum collegium”) in Kaffa, Khachikyan, Introduction to Yovhannēs K‘r. nets‘i, On Grammar, 42. The source for this is Clemens Galanus, Conciliatio, vol. 1, 523. The chapters “De progressibus fratrum praedicatorum in reducendis ad Catholicam fidem Armenis” (508–26) and “De Armeniorum episcopis ex Ordine fratrum praedicatorum assumptis” (527–531) are important sources for the fratres unitores.

-

17 Seidler, “Medieval Armenian Congregations in Union with Rome,” 152.

-

18 La Porta, “Armeno-Latin Intellectual Exchange in the Fourteenth Century,” 281.

-

19 For an overview of the translations in chronological order see Stopka, Armenia Christiana, 215–21.

-

20 See in detail, Seidler, Römische Liturgien.

-

21 Khachikyan, Introduction to Yovhannēs K‘ṛnets‘i, On Grammar, 35–38.

-

22 For the existing editions, see Appendix.

-

23 Oudenrijn, Linguae haicanae scriptores.

-

24 Khachikyan, Introduction to Yovhannēs K‘ṛnets‘i, On Grammar, 33.

-

25 Manuscript colophons mention him as the translator of Bartholomew’s, Peter of Aragon’s and John of Swinford’s works. On the other hand, some translations are attributed to Peter of Aragon and to Bartholomew. Peter and Yakob cooperated in translating other texts.

-

26 Oudenrijn, Linguae haicanae scriptores, 130 (Armenian text), 133 (Latin translation).

-

27 Minasyan, “Yovhannēs Orotnets‘i,” 16.

-

28 His Book of Questions is characterized as a real Summa, see Arevshatyan, “Grigor Tat‘ewats‘i and his Book of Questions,” 1.

-

29 The Hellenizing school’s translations of mainly scholarly and theological works were made roughly speaking from the late fifth to the early eighth centuries, and they bear considerable Greek influence. Many new words (among them terms) were coined, especially words with newly invented prefixes which corresponded to the Greek ἀντι-, συν-, περι, προσ-, etc. The use of such prefixes is the most striking feature of the Hellenizing translations, see Weitenberg, “Hellenophile Syntactic Elements in Armenian Texts”; Calzolari, “L’école hellenisante. Les circonstances”; Calzolari, “Les traductions Arméniennes de l’École hellénizante”; Tinti, “Problematizing the Greek Influence on Armenian Texts”; Muradyan, Grecisms in Ancient Armenian, 215–24, and Appendix 3: “Latinizing Armenian and its Relation to Hellenizing Armenian.”

-

30 Many of them were published in Europe, especially in Venice, Rome, Amsterdam, Marseille, Livorno and elsewhere.

-

31 Achaṛyan, History of Armenian Language, 311; J̌ ahukyan, History of the Grammar of Grabar, 8.

-

32 Zarphanalean, History of Armenian Literature, 45–55; Hambardzumyan, History of Latinizing Armenian, 27, 85.

-

33 Many of Esayi Nch‘ets‘i’s students, after attending classes in monasteries in which Latin bishops resided, became Franciscans or Dominicans, Stopka, Armenia Christiana, 212–13.

-

34 Cowe, “The Role of Priscian’s Institutiones Grammaticae,” 96.

-

35 La Porta, “Armeno-Latin Intellectual Exchange in the Fourteenth Century,” 280; Stopka, Armenia Christiana, 214.

-

36 It reveals that in 1337 fra Juan (John), the Englishman from the village of Swinford and a member of the order of Dominical Preachers, copied a compendium of works on the soul and its virtues and abilities, which was translated by Yakob the Armenian.

-

37 Khachikyan et al., Colophons of Armenian Manuscripts, 283: ի Վերին վանքս Քռնոյ, ընդ հովանեաւ Սուրբ Աստուածածնին, որոյ առաջնորդ էր՝ հոգաբարձու Յոհան վարդապետն, որ մականուն կոչի Քռնեցի, որոյ անուն շինեցին զսուրբ ուխտս աստուածասէր եւ բարեպաշտ պարոն Գորգն եւ ամուսինն իւր՝ տիկին Էլթիկն: Եւ սոքայ երեքեանն Յոհան վարդապետն եւ պարոն Գէորգն եւ տիկին Էլթիկն ինքնայօժար կամօք նուիրեցին զվանս կարգին քարոզողաց Սրբոյն Դօմինկիոսի՝ տուրք յաւիտենական։ Արդ, վերոյասացեալ վարդապետն Յոհան եղեւ պատճառ բազում օգտութեան եւ ժողովեաց աստ վարդապետք ի լատինացւոց եւ ի հայոց, տածելով զանմենեսեան ըստ հոգւոյ եւ ըստ մարմնոյ եւ թարգմանեաց եւ թարգմանէ գիրս բազումս ոգեշահս եւ լուսաւորիչս... եւ եբեր ազգիս Հայոց զփրկական համբաւն եւ առաջնորդեաց արժանաւորացն մտանել ի հնազանդութիւն գերադրական Աթոռոյն Հռօմա.

-

38 Oudenrijn, Linguae haicanae scriptores, 186. In addition to the MSs kept in Venice (V244, V681), Vienna (W263, W507) and Bzommar (90, 96) mentioned here, recently Sen Arevshatyan pointed to two MSs of Matenadaran, M5097 (14th c., 196r–213v) and M2183 (copied in 1662, fols. 433v–461r), see Arevshatyan, The Armenian Legacy of Bartholomew of Bologna, 25. The work also exists in MSs M3640 (14th c., 121r–150r), M842 (copied in 1738, 1r–142r) and M5375 (copied in 1841, 143v–164r).

-

39 Casella, Bartolomeo de Podio (da Bologna), 124–25.

-

40 Clemens Galanus, Conciliatio, vol. I, 510; Oudenrijn, Linguae haicanae scriptores, 177.

-

41 Clemens Galanus, Conciliatio, vol. I, 509; Oudenrijn, Linguae haicanae scriptores, 191.

-

42 Clemens Galanus, Conciliatio, vol. I, 522; Oudenrijn, Linguae haicanae scriptores, 192.

-

43 Oudenrijn, Linguae haicanae scriptores, 189. He also mentions MSs M842 (1738, the whole MSs), J486 (undated, 320–442), J574 (copied in 1718, 505–78r) and J1357 (copied in 1735, the whole MS). According to catalogues, all these MSs contain the same colophon, as the MS M3640.

-

44 Arevshatyan, The Armenian Legacy of Bartholomew of Bologna, 25.

-

45 Cited in Clemens Galanus, Conciliatio, vol. I, 513–22: “Epistola ad fratres unitos Armeniae,” Oudenrijn, Linguae haicanae scriptores, 203. Another letter written by Bartholomew in Armenian and stylistically revised by Yovhannēs is mentioned by Clemens Galanus (ibid., 510), see also Oudenrijn, Linguae haicanae scriptores, 176: “Epistola convocatoria ad synodum in conventu Qr. nayensi habendam (1330)”; Casella, Bartolomeo de Podio (da Bologna), 122.

-

46 This title is on the title-page of the edition. A longer title preceding the text reads: Համառօտ հաւաքումն յաղագս քերականին (A Short Compendium on Grammar), Yovhannēs K‘ṛnets‘i, On Grammar, 157.

-

47 This MS contains logical works of other unitores, but also David the Invincible’s Definitions of Philosophy, a Neoplatonic work translated from Greek in the late 6th c.

-

48 Dashian, Catalog, 719.

-

49 Oudenrijn, Linguae haicanae scriptores, 205. Oudenrijn’s opinion is repeated by Stopka with the following addition: “using examples from Armenian and Latin authors,” Armenia Christiana, 216–17. Casella too is unaware of the edition and the study of the grammatical work and repeats the same information, Bartolomeo de Podio (da Bologna), 123 (although a reference to the edition is found ibid., 231).

-

50 Yovhannēs K‘ṛnets‘i, On Grammar, 221: Ես Ֆրա Յոհան՝ մականուն կոչեցեալ Քռնեցի, համառօտ հաւաքեցի ի հայոց և լատինացոց զսակաւս ի բազում շարագրաց և ի քերթողաց, տալով դուռն և ճանապարհ նորամարզիցն՝ մտանել և ընթանալ ի քաղաքս իմաստից, զի ի հմտութենէ ելանել ի մակացութիւնս, և փոքրագունակ արուեստիւս՝ առ արհեստից արհեստն, որ է մայր և օթևանք և հանգիստ ընթերցելոցն առ խելս և իմաստութիւնս, իբր խթանաւ ընդոստեալ և ի դանդաչմանէ թմրութեանցն զարդեալ, զի ի ճանաչումն ճշմարտին և բարոյն եկեսցեն, որ է կատարումն բանականին.

-

51 So Cowe calls it “eclectic hybrid,” Cowe, “The Role of Priscian’s Institutiones Grammaticae,” 96.

-

52 Adonts‘, Dionysius the Thrax. This is regarded as the first translation of the so-called Hellenizing School in old Armenian literature (see above and footnote 29). More importantly, the translation of the Dionysian Ars grammatica initiated the Armenian literature on grammar. This translation created the bulk of the grammatical terminology which was used over the course of centuries and remains in use today. This translation also established the principles of how to coin an abstract and scientific lexicon in general. The most important Armenian grammatical terms (like their Latin counterparts) were calqued from Greek. The Armenian version of Dionysius’ grammatical work followed the word-order and syntax of the Greek original, Weitenberg, “Greek Influence in Early Armenian Linguistics.”

-

53 More precisely, between ca. 450 and the early 480s. There is also a later dating, namely the first half of the sixth century. The controversy concerning the process of dating the earliest translations is summarized in Muradyan, The Creation of the Armenian Grammatical Terminology, 76–111.

-

54 Avagyan, Introduction to Yovhannēs K‘ṛnets‘i On Grammar, 53, 69, 77, 79.

-

55 Khachikyan, Introduction to Yovhannēs K‘ṛnets‘i On Grammar, 48; Avagyan, Introduction to Yovhannēs K‘ṛnets‘i On Grammar, 114.

-

56 The citations from the text in question are followed by the page numbers of Yovhannēs K‘ṛnets‘i, On Grammar, which is the only edition of the work.

-

57 Avagyan, Introduction to Yovhannēs K‘ṛnets‘i On Grammar, 58. Avagyan argues that K‘ṛnets‘i’s classification of the types of syllables resembles Priscian’s classification into six categories (ibid., 67–68).

-

58 The anonymous translator of that work also adapted the Greek model to Armenian grammar, e.g. by introducing phonetical features and grammatical categories alien to Armenian (short and long vowels, short and long syllables, grammatical gender, dual number). He created whole paradigms of artificial verbal forms for verbal tenses non-existent in Armenian, etc. He did, however, also manage to reflect some features of Classical Armenian.

-

59 In Dionysius this title differs: “On Feet,” see Adonc‘, Dionysius the Thrax, 43.

-

60 See the underlying theory in Alessandro Orengo’s paper in this Special Issue.

-

61 Avagyan, Introduction to Yovhannēs K‘ṛnets‘i, On Grammar, 69.

-

62 The citations from Petrus’ commentary on Priscianus are followed by “Petrus” and the page numbers of Petrus Helias, Summa.

-

63 The citations from Priscianus are followed by “Pr.” and the book and page numbers of Prisciani Institutionum I–XII & XIII–XVIII.

-

64 Yovhannēs K‘ṛnets‘i, On Grammar, 169.

-

65 Most of them are used throughout the text, so references to pages do not seem reasonable.

-

66 The references to Armenian Dionysius are “Dion.” followed by page and line numbers of Adonts‘, Dionysius the Thrax.

-

67 The references to Greek Dionysius are indications of page and line numbers in Dionysius Thrax. Ars grammatica.

-

68 This term is made of the same components as նախդիր (prefix նախ- and root դիր/դր), with the addition of the suffix -ութիւն.

-

69 Those meaning “gender” (սեր), “masculine” (արական), “feminine” (իգական), “neuter (gender)” (չեզոք), “number” (թիւ), “nominative” (ուղղական), “genitive” (սեռական), “dative” (տրական), “accusative” (հայցական) “person” (դէմք), “tense” (ամանակ/ժամանակ), “present” (ներկայ), “future” (ապառնի), “past” (անցեալ) are the same.

-

70 This term is borrowed from the Greek ἐπίκοινον.

-

71 Yovhannes K‘ṛnets‘i, On Grammar, pp. 191 and 209.

-

72 Sirunyan, “The Latin Archetypes.”

-

73 Khachikyan had opined that the Armenian author either made use of both Priscianus and the commentary of Petrus Helias or even that he may have known Priscianus through the mediation Petrus, Khachikyan, Introduction to Yovhannēs K‘ṛnets‘i, On Grammar, 48.

-

74 Yovhannes K‘r. nets‘i, On Grammar, pp. 191 and 209.

-

75 Sirunyan, “The Latin Archetypes,” 135.

-

76 Corrected by the editor to անհոլով (“indeclinable”). Cf. the arguments against this correction, Sirunyan, “The Latin Archetypes,” 125–26.

-

77 The replacement of “Aeneas” by “so-and-so” and “Virgil” and “Socrates” by biblical names (section 2.3.3, example 22) is consonant with the common practice in earlier Armenian translations from Greek, e.g. Ἀλέξανδρος ὁ καὶ Πάρις (38.1), replaced by “Eleazar, who is also Avaran” (Dion. 19.19–20). For more examples see Muradyan, “The Reflection of Foreign Proper Names.” This wasn’t an absolute rule; in example 3 (2.3.3) Achilles’ name is preserved in the Armenian text. As to “Socrates” in example 21 (instead of “Priscianus”), his name was used by Aristotle in logical examples both in the Categories and in On Interpretation, which were accurately translated into Armenian in the sixth century and incorporated into commentaries on them, see Muradyan, Topchyan, “Commentaries on Aristotle’s Categories and On Interpretation.” Such use of Socrates’ name is also found in other Armenian commentaries on Aristotle.

-

78 Thurot, Extraits des manuscrits Latins, 357.

-

79 առանց նախադասութեանց; the related նախադասելով (instrumental of the infinitive) was calqued from προτασσόμενα (Dion. 5.14). Above նախադասի was rendered with praeponitur.

-

80 The translator confused the Latin adjective mutuus (the Latin phrase speaks of a “reciprocal relation”) and mutus (“mute”).

-

81 Such syntax is explained by the influence of the twelfth-century logical theories; the woman is both Eve and Mary. Кneepkens, “‘Mulier qui damnavit’,” 3.

-

82 Yovhannēs K‘ṛnets‘i On Grammar, 157–58; Cowe, “The Role of Priscian’s Institutiones Grammaticae,” 98.

-

83 Ibid., 99–100.

-

84 Ibid., 101–8.

-

85 Ibid., 110–12.

-

86 Cowe, “The Role of Priscian’s Institutiones Grammaticae,” 110.

-

87 Ibid., 114–17.

-