2025_1_Gal

The Administrative Elite of King Louis I in Croatia-Dalmatia

Judit Gál

HUN-REN Research Centre for the Humanities, Institute of History

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Hungarian Historical Review Volume 14 Issue 1 (2025): 30-64 DOI 10.38145/2025.1.30

This study examines the administrative elite that governed Croatia-Dalmatia under King Louis I of Hungary (1342–1382), focusing on the royal officials, urban leadership, and the mechanisms through which the king exercised authority in the region. Following the war between Hungary and Venice (1356–1358), King Louis I asserted control over Dalmatian cities, significantly altering governance structures by reducing urban autonomy and introducing new royal institutions. The study explores the composition of his administrative network, including the bans of Croatia-Dalmatia, royal admirals, municipal leaders, and royal knights drawn from local noble and patrician families. It also considers the fluidity of officeholding, the interplay between local and foreign administrators, and the integration of Italian and Hungarian officials into the region’s political framework. This paper provides insights into the strategies employed by King Louis I to consolidate power, the socio-political mobility within his realm, and the broader implications of Angevin rule in Dalmatia. The findings contribute to our understanding of medieval governance and territorial administration in Central and Southeastern Europe.

Keywords: medieval administration, King Louis I, Croatia-Dalmatia, Kingdom of Hungary, urban governance

During the reign of King Louis I (1342–1382), Hungary was in many respects in its golden era, having expanded its territories to an unprecedented extent. The king of Hungary, also referred to as the knight-king, led almost annual military campaigns, one of the most significant of which was the Hungarian-Venetian war of 1356–1358, which was fought for control of the Adriatic Sea and the possession of Dalmatia. Reclaiming the territories that had fallen into Hungarian hands in the early twelfth century and then had come under the rule of Venice in the first third of the fourteenth century had been one of Louis’ main objectives from the beginning of his reign, but his intrigues and campaigns for the throne in Naples prevented him from being able to take serious action in the 1340s. Between 1356 and 1358, the cities that had been in Hungarian hands in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, during the Árpád era, again were brought under the Hungarian king’s control.1 When King Louis I of Hungary defeated Venice in 1358 and the peace treaty was concluded in Zadar on February 18 of that year, the Kingdom of Hungary not only regained control of the Dalmatian territories previously under Hungarian control, but was also able to expand its territory (compared to the territories held in the Árpád era) to southern Dalmatia.

In the territories occupied by the king of Hungary, the settlement of the relationship between the royal power and the cities, which was sometimes not without conflict, began after the end of the war.2 The main source of tension in the settlement of power relations was the fact that, while in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries the Hungarian royal presence in the region was less noticeable and the cities enjoyed a high degree of autonomy, during the reign of Louis I, the Hungarian king intervened directly in the life and governance of local communities, significantly reducing urban autonomy.3 Louis introduced new royal institutions, hitherto known only in the narrowly defined Hungarian territories, and the presence of the royal power became much more visible, due in part to the officers delegated by the king, including the local, municipal leadership, which he appointed. Whereas in the Árpád era royal power had been represented in the region by practically a single royal official, the ban of Slavonia, and the archbishop of Split and the local prelates had been the most influential representatives of the monarch,4 in the second half of the fourteenth century a new stratum of leadership was formed, which ensured direct control of the region. After 1358, the newly established Hungarian financial administration, the leaders of the Hungarian naval fleet, and the municipal leaders appointed by the Hungarian king were added to the ban in the leadership structure, which ensured the sovereign’s power. Moreover, in the prime of the era of knightly culture, King Louis conferred knighthoods on a number of persons from Croatia and Dalmatia, making them directly part of the his household, the closest circle of the monarch. This paper will examine who constituted this layer of officials, or royal knights, through whom the king governed Croatia-Dalmatia and secured his power. It will focus on the urban communities and consider the overlaps among the various offices and the various forms of mobility between this region and the other territories ruled by the king of Hungary.

Composition of the Croatian-Dalmatian Administrative Leadership of King Louis I

The most important member of king Louis’ Croatian-Dalmatian administrative leadership was the ban of Croatia-Dalmatia, who traditionally governed the territory on behalf of the kings of Hungary from the beginning of their rule in in the region.5 Until the last third of the twelfth century, the power of the bans extended only to the territory of Croatia and Dalmatia, but by the end of the century, almost all of Slavonia was included in the Banate,6 so essentially with a few exceptions the territories beyond the Drava River under the rule of the kings of Hungary belonged to the governance of the bans. While the territory of the bans of Slavonia covered the area beyond the Drava River, for practical reasons, they occasionally appointed deputies who were solely responsible for Croatia-Dalmatia. These deputies were the bans of the Maritime Region.7 The ban’s power had already been divided between Slavonia and Croatia-Dalmatia during the Árpád era,8 and in the mid-fourteenth century, the Trans-Dravanian territory was divided into two banates (Slavonia, Croatia-Dalmatia).9 The bans of Croatia-Dalmatia governed the province in the name of the king, they were in charge of jurisdiction, financial administration, judiciary, military affairs, and they could appoint the local, royal officials. . The title of ban of Croatia-Dalmatia was one of the most important offices in the Kingdom of Hungary, and its holders were mostly Hungarian barons.10 In the period under study, the bans were John Csúz (1357–1358), Nicholas Szécsi, who held the office three times after 1358 (1358–66, 1374–1375, 1376–1380), and Charles of Durazzo, Duke of Slavonia, who also held the office of the ban twice (1372–74, 1376). Kónya Szécsényi (1366–67), Emeric Lackfi (1368), Simon Meggyesi (1369–71), Stephen Lackfi (1371), and Emeric Bebek (1380–83) also held the office at one time during this period.11 The bans of Croatia-Dalmatia, as will be shown in the following analysis, not only held national office in the period under study but also governed certain cities.

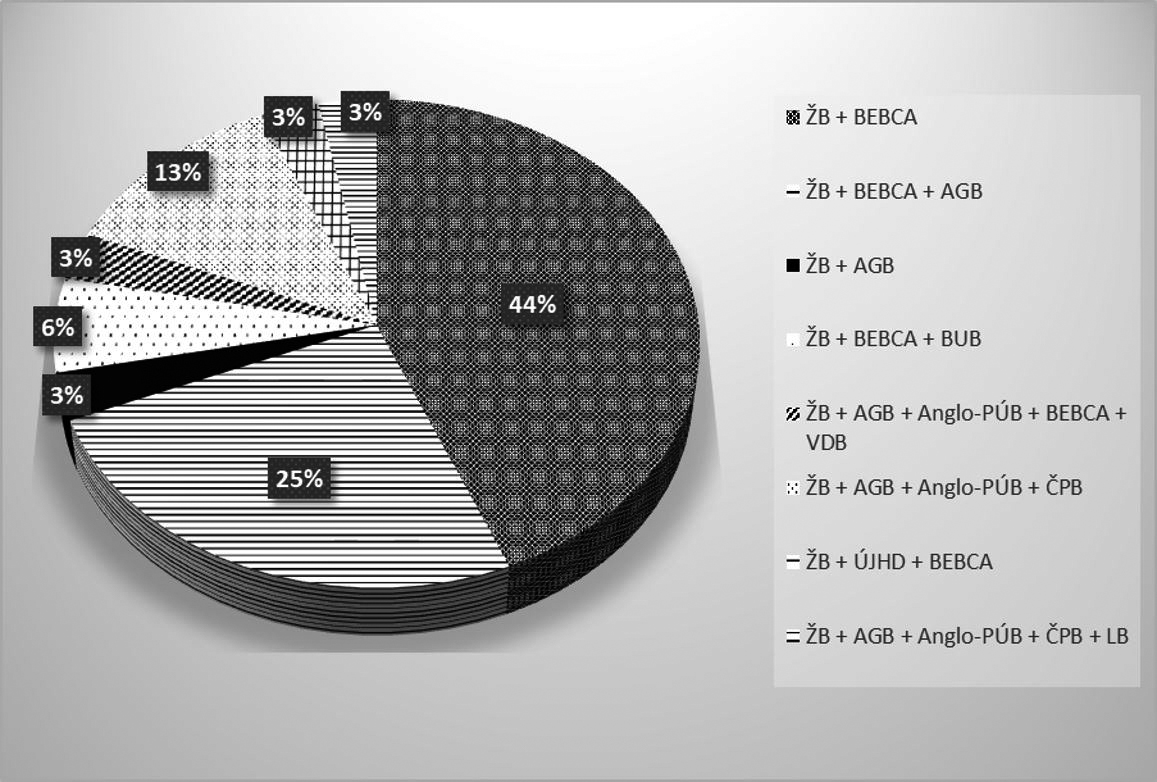

Alongside the bans, new royal officers also appeared in the region due to the establishment of royal institutions after 1358. Immediately after the end of the Hungarian-Venetian war, the Hungarian king assumed the monopoly of the salt trade and introduced a new tax, the tricesima or thirtieth, in Croatia and Dalmatia. The Treaty of Zadar also brought about the establishment of the Dalmatian-Croatian Salt and Thirtieth Tax Chamber. The exact timing of this occurrence remains uncertain due to the lack of sources, but it must have taken place shortly after Hungary took control of the region, since a charter from Trogir dated August 5, 1359 makes clear reference to the payment of the thirtieth and the ways in which salt was traded. The chamber continued to function until the beginning of the fifteenth century, ceasing to operate only with the capture of the city of Zadar by Venice in 1409. It is likely that the chief administrator of the Zadar Chamber was also the chief administrator of the entire Dalmatian-Croatian Salt and Thirtieth Chamber.12 Unfortunately, due to a lack of sources, very little information has survived on its functioning. The royal officials who were the heads of the chambers in the Dalmatian towns often leased out the chambers. The first known chief administrator (exactor) of the chamber was Baldasar de Sorba,13 who held the title in 1366, while also holding another royal office, that of admiral, also created in 1358.14 He was followed by Frison de Protto, the vicar of Senj, in 1367 who served until 1369 when Archdeacon Stephen of

Krk followed him. By 1372, the chamber was headed by George de Zadulino, a patrician from Zadar. However, by the mid-1370s, control of the chambers, particularly the chamber of Zadar had shifted to Florentine merchants,15 who, gradually overtook the positions of the Zadar merchants. They were heavily involved in trade in Dalmatia, particularly in the trade of salt.16

During the war against Venice between 1356 and 1358, the king of Hungary had probably already organized his naval fleet in 1357, and on February 10, 1358, the title of admiral was used for the first time to describe the leader of the king’s naval fleet. The first admiral was Jacob Cesamis, who held the title from 1358 until his death, and he was followed during the reign of Louis by Baldasar de Sorba (1366–1370). Baldasar served King Louis until around 1370, when probably he left the royal court to join King Louis’ ally, Prince Philip II of Taranto17 to serve as his bailli of the Principality of Achaea.18 While he returned to Croatia-Dalmatia after the death of Philip in 1373, but he didn’t become admiral again. In the admiral office, a fellow Genoese, Simon Doria (1373–1384) and Nicolaus Petracha (1373), who was from Split followed him.19 The admirals of the navy also held the title of comes of two islands, Hvar and Brač, from the beginning of the institution, and only later was the title of comes of the island of Korčula added to the offices that went with the title of admiral, presumably because Louis only occupied that island later, during the Hungarian-Venetian War.20

In addition to the aforementioned officers, there was also a completely new layer of high-ranking royal officials compared to the Árpád era through whom King Louis governed the region. After 1358, the heads of the Dalmatian cities, the comes, were formally elected by the cities, but in practice, the king decided the fate of the titles, except in the case of the city of Dubrovnik.21 How did this situation arise in regard to the autonomy of the cities? In the Árpád era, the autonomy of Hungarian cities was guaranteed by royal privileges. In Dalmatia, the Hungarian royal privileges of Trogir and Split were the basis for urban privileges and liberties for the cities in the region. These privileges guaranteed the cities the free election of a secular leader, who was the comes, and, if there was one, of an archbishop or bishop of the city.22 Except for a brief period during the reign of King Béla IV, there is no evidence of any direct interference by kings in the decisions of the cities.23 How did this landscape change during the reign of Louis I? In the course of the Hungarian-Venetian War between 1356 and 1358, the king recaptured a number of Dalmatian cities and cities which had previously been under Hungarian rule and confirmed their privileges at the request of the local cities and cities during the war. In August 1357, after Trogir and Split had come under Hungarian rule, Louis confirmed the former privileges of both cities. In the case of both cities, the confirmation of the privileges was done in a similar way: the representatives of the two cities presented their existing privileges, which the king confirmed without any changes. The privilege of Split was a charter issued on August 8, 1357, requested by a delegation from Split upon the formal submission of the city to the Hungarian king.24 The privilege of Trogir, dated August 30, 1357, can be described in a similar way to the charter of Split.25 The two charters were both clearly issued during the war. It was in the interests of the cities to confirm their privileges, and they sent envoys to King Louis, whose primary aim was to subjugate the cities, and he confirmed their charters without any reservations or qualifications. In 1357, king confirmed the privileges of Šibenik, which differed slightly from those of the two cities mentioned above.26 First, the charter, which was dated December 14, 1357, was issued to the city not by the king but on his behalf by the ban of Croatia-Dalmatia, John Csúz, after an envoy had been sent to the official in Nin. The privilege included confirmation of the privileges already enjoyed by the city, as well as details not seen in the previous Hungarian privileges of Šibenik, which reflected the contemporary needs of the city and included new obligations towards the monarch, such as the obligation to provide accommodation for the king. As the war drew to a close, a royal privilege was granted to Zadar by King Louis I of Hungary on February 10, 1358 guaranteeing, among other things, the preservation of the privileges of the city.27

Although the abovementioned privileges included the right of the cities to freely elect their authorities, in practice, the fate of the comes of the cities, who were the secular leaders of the urban communities, depended on the decisions made by the king, as his approval was required for the elected persons to take office.28 Approval meant that the king had his own candidate for the office, and he refused to support candidates proposed by anyone else. An example of this is the case of Split, where in 1367 the ban of Croatia-Dalmatia was to be elected comes, but the king refused to accept this and instructed the city to make the knight of the court, John de Grisogonis of Zadar, the comes.29 The heads of the cities can therefore be considered local officials of the monarch and can be included in the king’s local leadership layer.

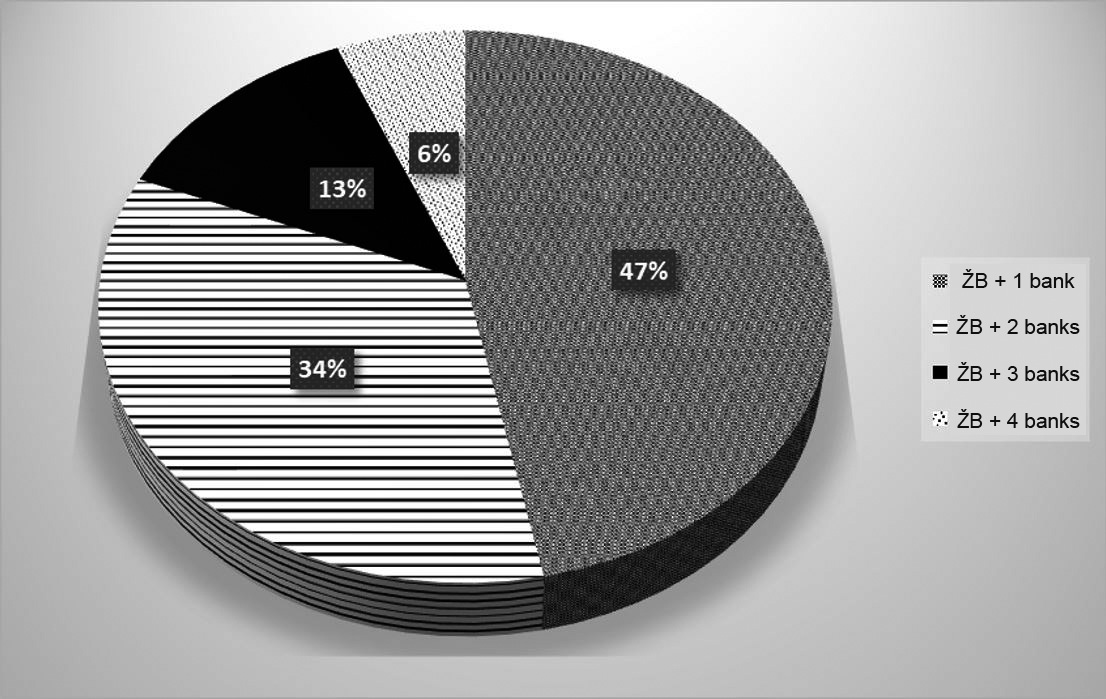

In addition to the royal officers and the leaders of the cities appointed by the king, a special group of Croatian nobles and selected citizens of the cities were formed, who had been granted knighthoods by Louis in the second half of the fourteenth century. The number of knights increased dramatically during Louis’ reign in Hungary, and this was particularly true in Croatia and Dalmatia, where a remarkably large number of Zadar citizens were awarded this distinction.30 The knights were part of the king’s inner circle, and they often accompanied him on military campaigns, having been assigned military or diplomatic duties or serving as ambassadors and liaisons between the Croatian-Dalmatian territories and the royal court. Many of them were citizens of Zadar who, in addition to their ad hoc duties, also held leadership positions in certain Dalmatian cities or other royal offices.

Royal Officials in Charge of Local Administration

The most significant change from the previous Hungarian royal policy, apart from the introduction of new institutions, was the acquisition of direct control over the cities during the reign of Louis I. The king’s influence and will was directly exercised through his officials in the cities of Dalmatia. In Croatia, the Hungarian system of counties had not been established, so the discussion of local administration will focus on the management of the royal castles. In the case of the cities, the analysis will focus on those settlements where adequate sources are available to identify the holders of the title of comes in the period. Those settlements are Zadar, Nin, Šibenik, Trogir, Split, Omiš, Hvar, Brač and Korčula, Rab, and the castles for which we have some information from the period and which were owned by the king.31 Excluded from the study are cities or islands that belonged to another landlord, such as settlements in the hands of the Counts of Krk, such as Senj,32 and the islands of Krk or Pag, which belonged to the city of Zadar, as well as Lastovo, where the election of the comes was the right of Dubrovnik, according to the decision of Louis I. Likewise, I have not considered the settlements, administrative units, or royal castles for which we do not have adequate data from the period. Of the castles, I have examined the royal castles and castles that were under the jurisdiction of the bans for which we have considerable data from the period. These included Klis, Knin, Novigrad, Obrovac, Omiš, two castles in the Croatian-Dalmatian area similarly called Ostrovica, Počitelj, Rmanj, Skradin, Sokol, Srb, Stog, Unac, and Zvonigrad.33

Among the cities, Zadar was the political center of the Dalmatian territories under Hungarian control during the reign of Louis, and already in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, when the territory was under Hungarian rule, the royal court considered this city its primary center.34 During the reign of Louis, Zadar became the economic and commercial center of the Kingdom of Hungary in Dalmatia. After 1358, Zadar became the center of the Dalmatian-Croatian Royal Salt and Thirtieth Tax Chamber, the Hungarian economic institution that was established in Croatia-Dalmatia that was mentioned earlier in this study.35 Then, Louis sought to boost trade between the Dalmatian territories and Hungary by offering privileges and concessions, such as exemptions from customs duties to merchants from Pozsony (Bratislava, Slovakia), Buda, Szeben (Sibiu, Romania), and Brassó (Brasov, Romania) to participate in Dalmatian trade based in Zadar.36 The political centrality of Zadar is attested to not only by the ties between the Hungarian administration and the local administrations but also by the fact that when Charles of Durazzo was granted the title of Duke of Slavonia in 1371, he held his court in Zadar, where his son was born, the future claimant to the Hungarian throne, Ladislas. During the Árpád era, when the city was briefly in Hungarian hands, the local comeses occasionally received the title of ban of the Maritime Region37 and, with it, command of the Hungarian army. After King Louis I took the city, this situation was reversed, and the ban of Croatia-Dalmatia acquired the title of comes of Zadar. As a look at the names of the comes of the period at the beginning make clear, the ban of the given year was at the head of the city. The list of the comeses of Zadar under King Louis begins at the end of November 135838 with Ban Nicholas Szécsi,39 who presumably received both offices at the same time. He was last mentioned as ban of Croatia-Dalmatia on August 9, 1366,40 but he was still listed as comes in the notarial records of Zadar at the end of November 1366.41

He was followed by Kónya Szécsényi, who was first mentioned in the sources as a ban on November 20, 1366,42 and one sources suggests that in December, 1366 he was the comes of Zadar.43 The last time his name appears in the sources in the office of the ban was on November 4, 1367,44 and the last time he appears as a comes of Zadar was in April 1368.45 While Emeric Lackfi was mentioned in the documents as a ban as early as January 30, 1368,46 the first mention of him as a comes of the city occurred only at the beginning of April 1368.47 He held the title of comes until the end of February 1369,48 but he probably left his office as ban of Croatia-Dalmatia at the end of October 1368.49 He was succeeded in both offices by Simon Meggyesi,50 who held the office of ban until around March 1371, when he was probably succeeded by Stephen Lackfi.51 However, Ban Simon was not succeeded as comes of Zadar by Lackfi but rather by Pietro Bellante in April 1371,52 who from 1367 was lord of two royal castles in Croatia, Ostrovica, Počitelj, and later was the lord of Obrovac.53 He became the first comes in Zadar after 1358 not to hold the title of ban. It cannot be ruled out that Stephen Lackfi’s and Pietro Bellante’s connections may have contributed to the granting of the office, since according to the contemporary chronicle of Domenico da Gravina, in the Neapolitan Wars54 Pietro was among the advisers of the commander of the Hungarian army, Voivode Stephen Lackfi of Transylvania, and he probably received the title of comes of Zadar around the same time of Lackfi’s tenure of office as ban of Croatia-Dalmatia in 1371.55

The year of 1371 can be considered a landmark in the history of the territories beyond the Drava River in the era of Louis, as it was then that Charles of Durazzo received the title of Duke of Slavonia (Croatia-Dalmatia) from the Hungarian king, what he held until 1376, and he established his own court in Zadar.56 From that moment on, the intertwining of the office of comes of Zadar and the office of the ban was loosened. During the dukedom of Charles, he himself bore the title of the ban of Croatia-Dalmatia on two occasions as well, and he was the first known ban of the region after the end of Stephen Lackfi’s tenure in 1371. For the first occasion, he was mentioned as the ban of Croatia-Dalmatia between October 1, 1372 and December 21, 1373,57 and he held the title of ban for the second time around between January and May 1376.58 Duke Charles did not hold the office of comes of Zadar during this period, nor was the connection between the office of ban and the title of comes evident in the case of other bans during his dukedom until the end of Louis’ reign. Pietro Bellante, who held the office of comes of Zadar in 1371, was mentioned in the sources as comes until March 1372, and he was not replaced by the ban of Croatia-Dalmatia after the end of his tenure.59

In addition to Charles of Durazzo, who did not hold the title of comes of Zadar during any of his terms of office until the end of his dukedom in Croatia-Dalmatia in 1376, there was one more known ban appointed in the period of his dukedom. Between November 1374 and February 1375, Nicholas Szécsi was mentioned as ban of Croatia-Dalmatia again, when he held the title for the second time, and later between May 1376 and December 1380, he was known to served once again as ban of Croatia-Dalmatia, for the third time (after 1358).60 He was followed by Emeric Bebek, who concluded the list of bans of Croatia-Dalmatia under the reign of Louis I.61 Bebek held the title after the death of the king until June 1383. Of the two, only Bebek held the office of the comes of Zadar during his entire tenure as ban,62 while Nicholas Szécsi was only mentioned as the comes of Zadar after the end of the dukedom of Charles of Durazzo between June 1378 and December 1380.63

After the end of Pietro Bellante’s tenure in office, which came to a close in 1372, for at least six years the bans were not elected as the comes of Zadar. After Bellante, it was not Charles of Durazzo or Nicholas Szécsi who took over the administration of the city but two brothers from Piacenza, Bishop John de Surdis of Vác (1372)64 and Rafael de Surdis (1372–1378).65 With their arrival in Croatia-Dalmatia from Hungary in 1372, a special legal situation arose for a short time in the region, as Charles of Durazzo was the duke Slavonia and the ban of Croatia-Dalmatia, and from 1372 to 1373, there was also a vicarius generalis (governor) authority in Croatia-Dalmatia, due to a mandate issued by the two de Surdis brothers. Shortly after Charles was given the title of Duke of Slavonia, in 1372, Bishop John de Surdis of Vác became vicarius generalis to the duke in the territories beyond the Drava River.66 In the spring of 1373, he was succeeded in this office by his brother Raphael,67 who is listed in the sources in this role until May 7, 1373.68 The vicarius generalis acted as governor of the province, as the ban of Croatia-Dalmatia had before. In the 1350s and 1360s, in (the Banate of) Slavonia, the vicarius generalis sometimes governed the province, but in these periods, there was no bans of Slavonia.69 The situation was different in Dalmatia and Croatia, where after 1372 there was a ban who served alongside the vicarius generalis, but this ban was none other than Charles of Durazzo, so the apparent contradiction between the coexistence of the two governing offices can be resolved, as the vicarious generalis was the deputy of Charles. This could also explain why the de Surdis brothers held the title of the comes of Zadar during their time in office as vicarius generalis. Since the title of comes of Zadar had previously been held by the ban, as primary deputy of the king, during the dukedom of Charles, the office of comes was held by the vicarius generalis, as primary deputy of the duke who governed the region. However, the presence of the office of vicarius generalis ended in the spring of 1373, and from 1374 until 1378, with a short term interruption when Duke Charles held the office of ban in 1376, there was again a ban of Croatia-Dalmatia at the head of the region. Despite the changes, the titleholder of comes of Zadar did not change in 1373, and the office was continuously held by Raphael de Surdis until 1378,70 probably by royal decree.

The city of Nin is located just 15 kilometers to the north of Zadar, and after Louis I took power in 1358, the first comes of the city was a royal knight from Zadar, John de Grisogonis, who held the post between 1359 and 1369.71 After 1369, the Croatian nobleman and royal knight Novak Disislavić of the Mogorović clan, who served the king in several campaigns and gained offices in Croatia, Dalmatia, and Hungary,72 had been given the title of comes of Nin three times by 1382 (1370–1371, 1373, 1381).73 In addition to Novak, John Rosetti (1373),74 John de Surdis (1373),75 and Rafael de Surdis (1375)76 were at the helm of Nin during the reign of Louis I, of whom the latter two both served as comes of Zadar during their tenure in office.

Moving southwards, in the city of Šibenik, like Zadar, the bans of Croatia-Dalmatia also held the title of comes, parallel to their country office after King Louis took over the territory. In the months following the Treaty of Zadar in February 1358, until the first half of 1359, no comes were elected in the city. The sources reveal only the names of the rectors, who were elected from among the local population and rotated on a monthly basis. The first comes during the reign of King Louis was Ban Nicholas Szécsi, who appeared in the sources as the comes of Šibenik between 1359 and 1362.77 He may have held this title throughout his entire term in office, but due to the lack of sources, we cannot confirm this. We have scattered data on other officials of the period, but it is certain that Kónya Szécsényi held the title in 136778 and Simon Meggyesi in 1370,79 both during their tenures in office as bans. Although we do not have such a richly detailed data set as in the case of Zadar, in my opinion, the developments in the case of Šibenik suggest that before 1371 the office of comes in this city also “belonged” to the holder of the office of the ban, as was true in the case of the title of comes in Zadar. This system also disappeared when Charles of Durazzo assumed the position as duke. The first known comes of the city from this period was Galeaz de Surdis from 1375,80 a relative of Raphael de Surdis and John de Surdis, who arrived to Dalmatia with John and Raphael, and was also the judge of the royal court of appeal in the Dalmatian cities in 1373.81 After him, no other is mentioned in the sources on the city until the death of Louis I.

In Trogir, the situation was quite different. After 1358, there was no presence of the bans of Croatia-Dalmatia among the leaders of the city. An almost unprecedented length of tenure in the Dalmatian cities was granted to the citizen and royal knight Francis de Georgiis of Zadar.82 The knight from Zadar was first mentioned in November 1358 as holding the latter office, which he held (with the exception of a one-year hiatus) until his death in 1377.83 When he had to leave office for a short period between 1373 and 1374, the title of comes remained in the family. King Louis had ordered Francis to Zadar because of the war with Venice,84 and in his place, the king appointed Francis’ son Paul, who was also a royal knight.85 After the death of Francis, the office of comes was given to another citizen of Zadar, Jacob de Raduchis, who was close to the royal court and had obtained a doctorate in law in Padua.86 He distinguished himself before the king in the 1370s and was, among other things, Louis I’s envoy at the negotiations concerning the Treaty of Turin in 1381.87 Between 1379 and 1382, the title was held by Baldasar de Sorba of Genoa, who was former admiral of the Hungarian fleet.88

Split was perhaps the most varied in terms of choice of comes compared to the previous cities. After February 1358, there was a transitional period following the Hungarian takeover. A podesta was appointed head of the city first, then from 1359 until 1363, as in Zadar and Šibenik, the office of comes was given to Nicholas Szécsi, the ban of Croatia-Dalmatia,89 who was succeeded by a royal knight from Zadar, John de Grisogonis, who was at the head of Split until from 1363 until 1369.90 He was succeeded in the city office by Raphael de Sorba, a royal knight, citizen of Zadar and son of the former admiral Baldasar. Raphael de Sorba held this position until 1372.91 After the Genoese comes, the title was held for two years by Giberto Cornuto, who is believed to have been related to the priors Peter and Bandon Cornuto of Vrana. 92 In 1374, another royal knight of Zadar, Maffeus Matafaris, became the head of the city,93 followed in 1379 by the then Croatian-Dalmatian ban Nicholas Szécsi for a short period,94 who probably received this title in connection with the war with Venice. In 1382, he was followed in the office by Jacob Szerecsen (Saracenus),95 who was sent as a royal visitor to Dalmatia and Croatia in 1370 and a year later received the islands of Cres and Osor as a royal gift.96

For Rab, we do not as many or as detailed sources from the period after 1358 as we do for the larger cities above.97 The first comes we know of from the reign of Louis is Gregory Banich, who is first mentioned as a comes of Rab in 1363,98 but presumably he could have been given this title as early as 1358.99 Gregory was the youngest son of the former Ban of Croatia, Paul Šubić,100 and he probably held the title until his death in 1374.101 After his death in 1374, Gregory was succeeded by Ban Nicholas Szécsi102 and then, around 1376, by the royal knight John Besenyő of Nezde,103 who from the 1370s onwards was shown to have been given more and more offices in Croatia and Dalmatia.104 He was succeeded that same year by Paul de Georgiis, who held the position until 1378.105 In 1381 and 1382, Count Stephen of Krk held the office.106

The fates of the leadership of the islands of Brač, Hvar, and Korčula were closely linked during the reign of King Louis. It is assumed that at the time of the establishment of the office of admiral or after the two islands had fallen into Hungarian hands the title of comes of Hvar and Brač was attached to the office of the head of the Hungarian fleet. During the reign of Louis, the admirals were systematically at the head of the two islands.107 The destiny of Korčula in the period under study was quite similar to that of the two islands above, with a few differences. After the island fell into Hungarian hands, the title of comes did not immediately pass to the admirals but was held by the royal knight Stephen de Nosdrogna at least in 1358.108 From 1361, the title was held by Jacob Cesamis, royal knight and admiral, recorded until 1364, probably until his death.109 He was succeeded in office by Admiral Baldasar de Sorba from 1366, who held the title until his retirement as admiral in 1370.110 He was briefly succeeded in 1372 by John de Surdis, vicarius generalis,111 and then by Admiral Nicolo de Petracha of Split (1373)112 and, after him, by Admiral Simon Doria of Genoa, who was comes of Korčula until 1384, when he was succeeded in his office as admiral and comes by Matheus de Petracha of Split.113

Less information is available about the leaders of Omiš. Only three comes are known from the reign of Louis I. In 1358, a royal knight from Zadar, Stephen de Nosdrogna,114 became the first to hold this position, followed by two royal admirals, Nicola de Petrache of Split (1373)115 and Baldasar de Sorba from Genoa (1369–1370), who held the office of comes, in addition to similar titles in Korčula, Hvar, and Brač.116 After them, no records of a comes of Omiš are known until the early fifteenth century. In the absence of sources, we can only speculate, but it is striking that two admirals were also comes of Omiš during their tenure, and we cannot rule out the possibility that this was also the case for the other admirals. The assumption of a connection between the office of admiral and the title of comes of Omiš is strengthened by the fact that, as in the case of Korčula, which later became the admirals’ estate, the first known comes of Omiš during the period of Louis’ reign was the royal knight Stephen de Nosdrogna (1358-1360). The connection of the office of admiral with the islands of Korčula, Hvar, and Brač and the city of Omiš is mainly due to the strategic location of this region for transport and trade on the Adriatic Sea, and it is no coincidence that it was the center of piracy on the Adriatic Sea for many centuries. As the area was crucial for safe navigation in the Adriatic, the evidence suggests that the granting of the titles of comes to admirals was a means of ensuring control of the sea.

After the analysis of the cities, we should briefly touch upon the question of the royal estates in Croatia, examining who were the heads of the royal castles. In Croatia, during the reign of Louis I, the royal castles were Knin, Klis, Unac, Srb and Počitelj, Ostrovica (Luka), Ostravica (Bužan), Omiš Castle, and Skradin Castle, Novigrad (after 1358), Zvonigrad (between 1363 and 1377), Amanj, Sokol, Peć (after 1368), and Obrovac (after 1379).117 These castles belonged to the honor of the bans of Croatia-Dalmatia and were therefore mostly headed by the ban’s men and familiars, making this layer less relevant for the study of the local elite of the ruler, since their relationship with the monarch was indirect. However, some names are worth highlighting, namely two individuals who established a strong foothold in Croatia-Dalmatia: Pietro Bellante and John Besenyő of Nezde. Both Bellante and Nezde had impressive careers in the region independent of the bans. They held leading offices in the cities as well as on the royal estates. John Besenyő, who was a royal knight, had an impressive career, though he did not gain influence beyond the Drava River until the late 1360s, after which he held important posts in the Dalmatian cities and Croatian territories. In 1374, for the preparation for Charles of Durazzo’s travel, the king sent Besenyő to Zadar.118 He was castellan of Obrovac in 1379 and comes of Bužan in 1380, but he may have held offices in the region earlier, as he is recorded as comes of Rab already in 1376, but given the lack of sources, we cannot arrive at a more complete picture of his career in Croatia-Dalmatia.119 John Besenyő of Nezde found his place in the region very well, as is indicated by the fact that later, after the death of Louis I, Queen Elizabeth sent him to Zadar and the Dalmatian cities to calm the troubled local society.120 Pietro Bellante was decorated in King Louis’ Neapolitan wars and in other conflicts in which he took part on the side of the king.121 As noted in the discussion above, the first records of Bellante’s presence in Croatia and Dalmatia date from the late 1360s, when he was counts of Bužan and Počitelj between 1367 and 1371, before becoming comes of Zadar. He had a flourishing career in Croatia-Dalmatia and in other parts of the Kingdom of Hungary.

The situation for the deputy heads of cities was similar to that for the heads of royal castles regarding their relevance to the royal administrative elite in Croatia-Dalmatia. The relationship between these deputies and the ruler was most of the time indirect with a few exceptions, since they were not appointed by the king or the duke of Slavonia, and their appointment and the office they held were usually determined by the comes, local political conditions, and practical considerations, and sometimes the comes even leased the office they held.122 Instead of a more detailed examination, it is worth noting a few trends that can be observed in the period between 1358 and 1382 in relation to the deputies regarding how the families of the royal officials were involved in the royal administration on a lower level. In the case of Zadar, the first deputy we know was Nicholas Debrői, a familiar of the Croatian-Dalmatian ban Nicholas Szécsi, whose name is mentioned in the sources in 1359.123 After the beginning of the dukedom of Charles of Durazzo, the records multiplied, and among the vicars, we find Nicolo Aldemarisco,124 who probably came from Naples with Duke Charles in 1371, and Galeazzo de Surdis, a relative of the then comes of Zadar, Raphael de Surdis,125 who took office in 1373, who had settled in Zadar and held other offices in Dalmatia, and Raymundus de Confalonieri, also of Rafael’s circle, who was of Piacenza origin and who was deputy between 1373 and 1375.126 In Split, we also find examples of the deputy role of the relatives of the comes, as Andrew de Grisogonis held this position between 1366 and 1367,127 when John de Grisogonis was the comes of the city. The phenomenon of deputies from among the relatives of the comeses can be traced in almost all the cities. For several years, Francis de Georgiis, who held the office of comes in Trogir for nearly two decades, had his son Paul,128 who himself briefly became the head of the city in 1373, as his deputy. We find examples of similar situations in the case of the royal admirals, with two of Baldasar de Sorba’s relatives replacing him as deputy in the office of the comes of Hvar and Brač, which was administered by the admiral: Raphael Rouere (de Sorba)129 in 1366130 and Nicolo de Sorba in 1367.131 Admiral Simon Doria’s deputy was Thomas Doria on the island of Korčula in 1375–1376,132 and Augustinus Doria was his deputy on Hvar in 1374133 and 1375,134 and the latter held the deputy post on Brač in 1381.135

Royal Knights from Dalmatia and Croatia as Officials of the King

During the reign of Louis, the king’s circle of local leadership was reinforced by a particular group, a narrow circle of people. They were the citizens and nobles from Croatia and Dalmatia who had been knighted by Louis during his reign. The reign of Louis was the heyday of chivalric culture in Hungary,136 and the number of royal knights increased dramatically, even more spectacularly than the national increase in Croatia and especially in Dalmatia, due to the large number of citizens mostly from Zadar who received this honorable title.137 Two members of the de Georgiis family from the city of Zadar were among the knights of the court. The name Francis is mentioned in sources from 1345 as a member of the Zadar delegation that sought military assistance against Venice,138 and his son Paul is first referred to by this title in the sources from 1377.139 Jacob Cesamis’ family was among the first to be given this title by Louis I. He was first mentioned in the sources as a knight of the court in 1358, before the Peace of Zadar, when, together with Daniel de Varicasso and George de Georgio, he came before Louis I as a delegate from Zadar to ask the king to confirm the old privileges the city had enjoyed. 140 Stephen de Nosdrogna is mentioned as royal knight in a source from 1358.141 John de Grisogono was a member of the Zadar delegation that sought out King Louis in 1357 and asked him to put the city under his protection.142 One can plausibly assume that he was granted the title in connection with the role he played as part of this delegation. Paul de Grubogna first appeared before the king as a figure of some influence in 1345, when, together with Francis de Georgio, he too went as part of the aforementioned delegation to the Hungarian king’s court. Unlike his predecessors, Mafej de Matafaris did not catch the attention of the king in the 1340s and 1350s, as he was too young to have done so. He was first mentioned in the sources as a knight in 1376.143 Jacob de Varicasso is first mentioned in the sources from 1357, when he appeared before the king as a member of the aforementioned delegation from Zadar, and presumably, like John de Grisogono, he was knighted at the time, though in the sources, he was only referred to by this title in 1363.144

In addition to the citizens of Zadar, other royal knights from the region are also known. Among them, one of the major players among the royal officials was Novak from Lika, a member of the Mogorović clan.145 While his fellow knights of Zadar served mainly locally, Novak’s name is also found in Hungary in the king’s entourage. He took part in the royal hunt at Zólyom (present day Zvolen) in 1353, where, according to the chronicle of the Anonymus Minorite, his intrigues prevented John Besenyő, who had actually rescued the king, from receiving a reward.146 He is also known for his literary activities. He received titles both in Hungary, as castellan of Salgó,147 and in Croatia-Dalmatia, including the count of Nin multiple times. Novak was rewarded by the Emperor with the title of Royal Knight by 1351 at the latest, and in 1352, he and his two brothers, John and Gregory, were granted land near Počitelj.148 The charter mentioned that his father had fought and fallen on the king’s side against the Venetians, probably in the siege of Zadar in 1345, where Novak himself was seriously wounded, but he was also wounded in the king’s campaign in Naples, and he even marched on the king’s side against the Lithuanians to take the castle of Belz, which was probably the direct reason for the grant.149

To be awarded a knighthood, those who received this honor had to distinguish themselves personally before the king. Most of their achievements were either diplomatic missions or military deeds, therefore it can be assumed that most of the citizens of Zadar were awarded the title for their actions during the siege of Zadar in 1345–1346 and the Hungarian-Venetian war from 1356 to 1358. In 1345, Francis de Georgiis and Paulus Grubogna were members of the Zadar envoy delegation that asked King Louis for help against Venice. Jacob Varicassis and John de Grisogonis were also ambassadors to the royal court in 1357. Jacob Cesamis commanded ships against Venice during the siege of Zadar, and was later imprisoned for a long time. The royal knights, who were drawn from the local burghers and nobles, were also supported the monarch in the management of the local administration and served as a link between the region and the court. In addition to his offices in Hungary, Novak served as comes of Nin three times, John de Grisogonis was comes of Nin (1359–1369) and Split (1363–1369), the latter city being also governed by Mafej de Matafaris (1374–1379), Stephen de Nosdrogna was in charge of Omiš (1358) and Korčula (1358), Francis de Georgiis family was in charge of Trogir (1358–1373, 1374–1377), his son Paul was also comes of Rab (1376–1378) and Trogir (1373), and, as can be seen, their family members and relatives were deputies in the administration of the Dalmatian cities alongside them or alongside other comeses. Examples of this are the cases of Andrew de Grisogonis in Split (1366–1369) and Paul de Georgiis in Trogir (1363–1370). Royal knights were often found as envoys of the king, in times of war and peace. In 1359–1360, Jacob Cesamis and John de Grisogonis acted as ambassadors alongside Nicholas Szécsi in negotiations with Venice.150 In 1368, Stephanus de Nosdrogna was ambassador to Pope Orban V on behalf of the king,151 and Mafej Matafaris and Paulus de Georgio were involved in the conclusion of the war with Venice and the peace of Turin in 1381, as was Jacob Raduchis, who did not hold the title of knight but enjoyed the king’s favor.152 The knights played a liaison role between the region and the court, as exemplified by the request of the rector, councilors, and magistrates of Dubrovnik to Francis de Georgiis to inform the city through their envoys of the details of the king’s visit to Dalmatia and to signal the city when the monarch was on his way to Zadar.153

Mobility between Various Parts of the Country

During the reign of Louis I, the Dalmatian-Croatian the king’s local, administrative leadership consisted basically of two groups: local Croatian nobles and Dalmatian burghers, who were chosen by the king, and others from Hungary and Italy who came from outside Croatia-Dalmatia. The question is the degree of mobility between Croatia-Dalmatia and the rest of the Kingdom of Hungary. In the case of the burghers who belonged to the elite of Louis, the main characteristic we have seen in their careers is that they often played leading roles in the local administration and they were involved in political affairs affecting the region, provided a link between Croatia-Dalmatia and the royal court, but they did not participate in national politics and did not hold country-level offices. There are a number of explanations for this. First, the ruler needed a certain stratum of people who were familiar with local and regional social and political circumstances to govern the newly acquired territories. The nucleus of the king’s local, administrative elite was formed in the 1340s and 1350s, during the siege of Zadar and the Hungarian-Venetian war.154 It consisted of the royal knights of Zadar who, either through their military actions or otherwise, had distinguished themselves personally before the king. Louis’s Croatian-Dalmatian administration was based on the use of reliable, small numbers of local royal knights in the management of the region. The members of this local elite were completed by royal officials coming from Hungary or Italian towns with similar roles compared to the local knights, thus forming the king’s local administrative leadership, among whom were also several royal knights, such as Baldasar and Raphael de Sorba of Genoa, or John Besenyő of Nezde.

This system was not unprecedented. In the Kingdom of Naples in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, almost exclusively knights were employed as district judges (giustiziariato), often sent to the peripheries of the kingdom. The choice of these officers who governed these border areas was made deliberately and combined local members with those from other parts of the country, particularly Provence. These individuals were responsible for representing the king’s interests in the territory and for keeping the peace, and they were also given military, judicial or even financial tasks. The people chosen to govern these areas were expected to be loyal rather than to have special knowledge, and could hold a variety of offices during their term of duty. The royal officers sent to the peripheries were also assigned to various types of duties beyond the country’s borders, mainly military or diplomatic.155 A fundamentally similar phenomenon can be observed during the Angevin rule of the England in the thirteenth century, where royal local royal were trusted with judicial role.156

The officers of local origin of King Louis, whether they were royal knights or other patricians who had not received such recognition, do not appear to have been involved in affairs in other parts of the Kingdom of Hungary, but only in foreign policy matters affecting the region. Only those royal knights who belonged to the local nobility and who were able to support the royal campaigns with soldiers were able to achieve national recognition and were rewarded with offices. Novak was a member of the king’s retinue, and he took part in his wars and campaigns, thereby acquiring his own privileges in Hungary. During the reign of Louis I, there was probably no royal will to bestow offices and privileges on the urban knights in Hungary, and only the period of political turmoil and throne struggles in the later decades gave the opportunity for descendants of former royal knights from Dalmatian cities (and some members of their families) to gain a foothold in Hungary. Among the royal knights of Zadar who had won this title during the reign of Louis, one family managed to gain a foothold among the Hungarian nobility later. The Zubor family of Földvár and Pataj were descendants of the Nassis and Cesamis families from Zadar.157 Jacob Cesamis was the grandson of Admiral Jacob Cesamis and son of the royal knight and admiral Matthew Cesamis. He used the name Jacob Zubor Pataji instead of Cesamis, presumably because of the estate of Pataj (now Dunapataj), which he received as a royal grant.158 Zoilo and John Nassis, who were related to Jacob Zubor of Pataj on their mother’s side, had even more spectacular careers. They established themselves among the Hungarian national elite, but much later, during the reign of King Sigismund.

From Hungary and other provinces of Louis’s kingdom the entrance to Dalmatia and Croatia was open. There were two main groups of people who arrived in the region, those coming directly from Italy and those coming from Hungary. The latter included persons of Hungarian and Italian origin the vast majority of whom belonged to the Italian group, who could easily integrate into an environment, economic structures, and society that was not unfamiliar to them. Among those from Hungary, the Croatian-Dalmatian bans, vicarius generalis, and their familiars were temporary “guests” in the region, since their role in local institutions and their offices lasted as long as they held the high office of the kingdom, but once they had lost it, they did not retain any other offices in Dalmatia. An exception to this was Raphael de Surdis, who was vicarius generalis and also comes of Zadar in the spring of 1373 but who remained in Dalmatia after his mandate as governor had ended and was referred to in the sources as the comes of Zadar and the comes of Nin until 1378. Among the officials of the Hungarian monarch, the admirals of the fleet were in a very different position compared to the bans. They were not from the Hungarian nobility. They were either local men skilled in naval warfare, such as the royal knight Jacob Cesamis or Nicholas de Petracha of Split, or experienced Genoese sailors, such as Baldasar de Sorba and Simon Doria, who settled comfortably in the region.

Among those who arrived from outside of Croatia and Dalmatia, there was a strikingly large number who had come directly from Italy or were of Italian origin but had already had impressive careers in Hungary. Many of them had put down roots in the region, and they were involved in local trade and economic life, in addition to the roles they played in their offices. These people were sometimes the link between the Kingdom of Hungary and the cities of Italy. An excellent example of this is the case of Florence, when in 1365 the city asked Baldasar de Sorba, the officer of the king in Dalmatia, to recommend the Florentines to the favour of the king.159 This tendency could be observed in the management of the Hungarian salt and thirtieth tax chamber offices in Dalmatia, where Florentine merchants and financiers took over the administrative leadership from the 1370s.

Among the leaders of the administration of the Hungarian king in Dalmatia and Croatia of Italian origin, the de Surdis of Piacenza brothers occupied a prominent place, due to the fact that these two men held the office of vicarius generalis successively.160 In addition to John and Raphael de Surdis, who were in charge of the administration of the region, other relatives and presumably also members of their circle from Piacenza arrived with them, such as Galeaz de Surdis and Raymond Confalonieri. We do not know why Louis I entrusted the office of vicarius generalis and other offices in Croatia-Dalmatia to the de Surdis family. John de Surdis, who himself had had a close relationship with the Hungarian king through another bishop from Piacenza, Jacob of Zagreb, was the king’s envoy to the papal court in Avignon on several occasions in the 1360s, so it is clear that he was one of the king’s confidants. To all this we might add that they were not the first members of the de Surdis family to play a significant role in the region. Francis de Surdis, the son of Manfred, had been notary in Zadar from 1349 to 1350161 and then in Split (1356–1358)162 and finally in Dubrovnik in 1360.163 This may not have had any influence on John’s or Raphael’s appointment as vicarius generalis, but it is possible that they were better acquainted with local affairs through their kinship. Although the family had initially settled in Zadar, they eventually won Lipovec as a donation from Louis I, and the donation included his brothers and the son of an unnamed brother. The family’s history was then mainly connected with the county of Zagreb and their estate.164

From among the arrivals from outside of Croatia-Dalmatia, the members of the de Sorba and Doria families of Genoa settled in Dalmatia as well. Baldasar de Sorba and Simon Doria were in command of Louis I’s fleet. The former was also involved in the chamber of salt and thirtieth tax in Dalmatia and Croatia, and both families were active in trade and finance. The emergence of the two Genoese admirals was due to the close alliance between the Hungarian king and Genoa, from where experienced leaders came to head the Hungarian fleet. Baldasar de Sorba may have arrived in Dalmatia in the early 1360s, settling in Zadar, and then becoming a royal shipbuilder, head of the Dalmatian-Croatian salt and thirtieth chamber, and royal admiral from 1366. He left this post around 1370 and was Philip II of Taranto’s governor in the Principality of Achaea during his dukedom until 1373. Baldasar and the de Sorbas were not disconnected from Zadar, as he is believed to have returned to Dalmatia after 1373 and was appointed by the king as comes of Trogir between 1379 and 1381. The de Sorbas became part of the Zadar citizenry, Baldasar was joined in the region in the 1360s by his brother Nicolo, who was Baldasar’s deputy in 1367 on the island of Hvar. Also related to Baldasar was Raphael Rouere (de Sorba), who was the admiral’s deputy on the islands of Hvar and Brač in 1366. Baldasar’s greatest aid and companion in the region was his own son Raphael, who also served as comes of Split during the period, and after the death of Louis he also held the office of comes of Šibenik (1384) and was given offices in Zadar, including being elected rector and judge on several occasions.165

The members of the Genoese families were easily integrated into Dalmatian urban society and local trade, as evidenced by the numerous records of their activities.166 Among the members of the Doria family, in addition to Simon, his brothers Bartol and Hugolin were engaged in trade, and Augustinus Doria is found as the deputy of the admiral in Hvar. The later admiral of the naval fleet of King Sigismund was Hugolin Doria, but he no longer lived in Zadar, as the city was in Venetian hands, and he established his headquarters in Trogir.167 In addition to the royal officers, the Genoese presence in the region was significant during the reign of Louis I. This was due not only to the fact that royal officials from Genoa were present, but also to the fact that Genoese merchants enjoyed trade privileges in Hungary that the Florentines could only have wished for in the 1370s.168 Beside the de Sorbas and Dorias, the Spinola family, which was one of the most important in Genoa at the time,169 was represented in the region thanks to their commercial activities.170

Apart from those from Piacenza and Genoa, the presence of the Neapolitans among Louis I’s Dalmatian-Croatian leaders is most notable. Pietro Bellante, who distinguished himself as an adviser to the Hungarian king in his campaign in Naples in 1349 and acquired a patrimony in Transylvania in the 1360s, then acquired positions of leadership in Počitelj, Bužan, and Obrovac as well as the office of Zadar. Although Nicolo Aldemarisco was not a comes of any Dalmatian city, he was deputy comes of Zadar after 1371, probably due to Charles of Durazzo. His relative Luigi Aldemarisco later became admiral to Charles’ son, Charles of Naples, who was fighting for the Hungarian throne. From among those who came from the Hungarian territories, two are worth mentioning: John Besenyő of Nezde and Jacob Szerecsen of Padova, who were appointed to the leadership of Dalmatian cities without holding a national office in Croatia-Dalmatia. The royal knight Besenyő and Szerecsen, who played the most prominent roles in the management of the Hungarian financial administration in the 1370s, had not only a distinguished career in Hungary in the narrow sense of the word (i.e. not only in the territories of what at the time would have been considered Hungary proper) but also in Croatia-Dalmatia. Besenyő was the only Hungarian nobleman who was comfortably and securely settled in Croatia-Dalmatia, but his example illustrates that there was a door for mobility.

Archival Sources

Nadbiskupski Arhiv u Splitu [Archbishopric Archive in Split] (NAS)

Rukopisna građa Ivana Lučića MS 528, 531–542

Magyar Nemzeti Levéltár Országos Levéltára [Hungarian State Archives] (MNL OL)

Diplomatikai Fényképgyűjtemény [Diplomatic photo collection] (DF)

Diplomatikai Levéltár [Diplomatic archive] (DL)

Državni arhiv u Zadru [State archive in Zadar] (DAZd)

Curia maior ciuilium (CMC)

Korčula (KA)

Spisi zadarskih bilježnika [Documents of Zadar Notaries] (SZB)

Petrus Perençanus (PP)

Vannes condam Bernardi de Firmo (VBF)

Nacionalna i sveučilišna knjižnica, Zagreb [National and University Library, Zagreb] (NSK)

Bibliography

Printed sources

ADE = Magyar diplomácziai emlékek az Anjou-korból. Acta extra Andegavensia I–III [Hungarian diplomatic records from the Angevin era]. Edited by Gusztáv Wenzel. Budapest: MTA, 1874–1876.

Anjou oklt. = Anjou-kori oklevéltár I–XV., XVII–XXXVIII., XL., XLII., XLVI–XLIX., L. [Charters of the Angevine era]. Edited by Gyula Kristó et al. Szeged–Budapest: Szegedi Középkorász Műhely, 1990–2020.

B. Halász, Éva, and Ferenc Piti. Az Erdődy család bécsi levéltárának középkori oklevélregesztái 1001–1387 [The medieval charter registers of the Erdődy family’s Vienna archive 1001–1387]. Budapest–Szeged: Magyar Nemzeti Levéltár Pest Megyei Levéltára, 2019.

CDCr = Codex diplomaticus regni Croatiae, Sclavoniae et Dalmatiae. Vols. 1–18. Edited by Tadija Smičiklas. Zagreb: JAZU, 1904–1934.

Krekich, Antonio. “Documenti per la storia di Spalato (1341–1414).” Atti e memorie della Società Dalmata di Storia Patria 3/4 (1934): 57–86.

Listine = Listine o odnošajih izmedju južnoga Slavenstva i Mletačke Republike [Documents on the relations between the Southern Slavs and the Republic of Venice]. Vols. 1–10. Edited by Šime Ljubić. Zagreb: Albrecht, 1868–1891.

Rački, Franjo. “Notae Joanni Lucii.” Starine JAZU 13 (1881): 83–124.

Serie dei Reggitori di Spalato. Bullettino di archeologia e storia dalmata 10 (1887): 198–99; Bullettino di archeologia e storia dalmata 11 (1888): 62–64, 76–77, 94–96.

Šišić, Ferdo. “Ljetopis Pavla Pavlovića Patricija Zadarskoga.” Vjesnik Kr. Hrvatsko-Slavonsko-Dalmatinskog Zemaljskog Arkiva 6 (1904): 1–59.

Spisi splitskog bilježnika = Grbavac, Branka, and Damir Karbić, and Arijana Kolak Bošnjak. Spisi splitskog bilježnika Albertola Bassanege od 1368. do 1369. godine. Zagreb: Hrvatska akademija znanosti i umjetnosti, 2020.

UGDS = Urkundenbuch zur Geschichte der Deutschen in Siebenbürgen. Vols. 1–7. Edited by Gustav Gündisch et al. Hermannstadt–Bucharest: Franz Michaelis, Georg Olms. 1892–1991.

Varjú, Elemér. Oklevéltár a Tomaj nemzetségbeli Losonczi Bánffy család történetéhez [Charter collection for the history of the Losonczi Bánffy family of the Tomaj clan]. Budapest: Hornyánszky Viktor Könyvnyomdája, 1908.

Velika bilježnica = Karbić, Damir, Maja Katušić, and Ana Pisačić. Srednjovjekovni registri Zadarskog I Splitskog kaptola (Registra Medievalia Capitulorum Iadre et Spalati). Vol. 2, Velika bilježnica Zadarskog kaptola (Quaternus magnus Capituli Iadrensis). Zagreb: Croatian State Archives, 2007.

Vuletić Vukasović, Vid. Catalogo dei Conti, Vicari e Rettori che si succedettero nel governo di Curzola (Dalmazia) dall’ anno 998–1796. Dubrovnik: n.p., 1900.

Secondary literature

Albini, Giuliana. “Piacenza dal XII al XIV secolo: reclutamento ed esportazione dei podestà e capitani del Popolo.” In I podestà dell’Italia comunale: Reclutamento e circolazione degli ufficiali forestieri (fine XII sec.-metà XIV sec.), edited by Jean-Claude Maire Vigueur, 405–45. Rome: École française de Rome, 2000.

B. Halász, Éva. “Generalis congregatiók Szlavóniában a 13–14. században” [General congregations in Slavonia in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries]. Történelmi Szemle 59 (2017): 283–98.

Bartulović, Anita. “Integracija došljaka s Apeninskog poluotoka u zadarskoj komuni (1365.–1374.)” [Integration of immigrants from the Italian peninsula in the Zadar commune (1365–1374)]. Radovi Zavoda za povijesne znanosti HAZU u Zadru 61 (2019): 135–77.

Bećir, Ante. “Plemstvo kasnosrednjovjekovnoga Trogira: politička zajednica, frakcije i dinamika konflikta” [The late medieval nobility of Trogir: political community, fractions and dynamics]. PhD diss., Zagreb, Hrvatsko katoličko sveučilište, 2022.

Bettarini, Francesco. “Notai-cancellieri nella Dubrovnik tardo medievale.” Italian Review of Legal History 7 (2021): 691–718.

Botica, Ivan, and Antun Nekić. “A Feather or a Sword? About Count Novak and His Glagolitic Missal.” Konštantinove Listy 17 (2024): 36–46.

Brătianu, George. “Les Vénitiens dans la mer Noire au XIVe siècle, après la deuxième guerre des Détroits.” Revue des études byzantines 33 (1934): 148–162.

Brković, Milko. “Ugovor o sklopljenom miru u Zadru 1358. između Ludovika I Venecije” [Treaty on peace concluded in Zadar in 1358 between Louis and Venice]. In Humanitas et litterae: Zbornik u čast Franje Šanjeka, edited by Lovorka Ćoralić, and Slavko Slišković, 205–22. Zagreb: Kršćanska sadašnjost, 2009.

C. Tóth, Norbert. A kalocsa-bácsi főegyházmegye káptalanjainak középkori archontológiája [The medieval archontology of the chapters of the Kalocsa-Bács archbishopric]. Kalocsa: KFL, 2019.

C. Tóth, Norbert. Az esztergomi székes- és társaskáptalanok archontológiája 1100–1543 [Archontology of the Cathedral and Collegiate Chapters of Esztergom 1100–1543]. Budapest: MTA, 2019.

Confalonieri, Giuseppe. Monografia della nobile famiglia Confalonieri di Piacenza. Firenze: Stab. Ramella, 1923.

Csákó, Judit. “A padovai krónikák, Nagy Lajos és a guerra dei confine” [The Padua chronicles, Louis the Great, and the guerra dei confini]. Világtörténet 13 (2023): 251–77.

Csukovits, Enikő. Az Anjouk Magyarországon. Vol. 2, I. Nagy Lajos és Mária uralma (1342–1395) [The Angevins in Hungary. Vol. 2, The reign of King Louis I the Great and Queen Mary, 1342–1395]. Budapest: MTA Történettudományi Intézet, 2019.

Dokoza, Serđo, and Mladen Andreis. Zadarsko plemstvo u srednjemu vijeku [The nobility of Zadar in the Middle Ages]. Zadar: Sveučilište u Zadru, 2020.

Draskóczy, István. “András Kapy: Carrière d’un bourgeois de la capitale hongroise au début du XV e siècle.” Acta Historica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 34 (1988): 119–57.

Engel, Pál. Magyarország világi archontológiája 1301–1457. Budapest: História, MTA Történettudományi Intézete, 1996.

Fabijanec, Sabine Florence. “Pojava profesije mercator i podrijetlo trgovaca u Zadru u XIV. i početkom XV. stoljeća.” Zbornik Odsjeka za povijesne znanosti Zavoda za povijesne i društvene znanosti Hrvatske akademije znanosti i umjetnosti 19 (2001): 83–125

Fekete Nagy, Antal: A magyar-dalmát kereskedelem [Hungarian-Dalmatian trade]. Budapest: Egyházmegyei Könyvnyomda, 1926.

Gál, Judit. “The Roles and Loyalties of the Bishops and Archbishops of Dalmatia (1102–1301).” Hungarian Historical Review 3 (2014): 343–73.

Gál, Judit. “Zadar, the Angevin Center of the Kingdom of Croatia and Dalmatia.” Hungarian Historical Review 11, no. 3 (2022): 570–90. doi: 10.38145/2022.3.570

Gál, Judit. “The Changes of Office of Ban of Slavonia after the Mongol Invasion in Hungary (1242–1267).” In Secular Power and Sacral Authority in Medieval East-Central Europe, edited by Suzana Miljan, and Kosana Jovanović, 37–48. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2018.

Gál, Judit. Dalmatia and the Exercise of Royal Authority in the Árpád-Era Kingdom of Hungary. Budapest: Research Centre for the Humanities, 2020.

Gerő, Győző. “II. ker. Fő utca 82–84. sz.” [Budapest, II district, Fő utca 82–84.] Budapest Régiségei 19 (1959): 266.

Grbavac, Branka. “Notari kao posrednici između Italije i Dalmacije: studije, službe, seobe između dvije obale Jadrana.” Acta Histriae 16, no. 4 (2008): 503–26.

Grbavac, Branka. “Prilog proučavanju životopisa đenoveškog i zadarskog plemića Baltazara de Sorbe, kraljevskog admirala” [Contribution to the study of the biography of the Genoese and Zadar Nobleman Baltazar de Sorba, royal admiral] In Humanitas et literae: Zbornik u čast Franje Šanjeka, edited by Lovorka Čoralić, and Slavko Slišković, 227–40. Zagreb: Kršćanska sadašnjost, 2009.

Grbavac, Branka. “Prilog proučavanju životopisa zadarskog plemića Franje Jurjevića, kraljevskog viteza” [Contribution to the study of the biography of the Zadar nobleman Franjo Jurjević, royal knight]. Zbornik Odsjeka za povijesne znanosti Zavoda za povijesne i društvene znanosti Hrvatske akademije znanosti i umjetnosti 22 (2004): 35–54.

Grbavac, Branka. “Zadarski plemići kao kraljevski vitezovi u doba Ludovika I. Anžuvinaca” [Nobles of Zadar as royal knights in the era of Louis I]. Acta Histriae 16 (2008): 89–116.

Györffy, György. “Szlavónia kialakulásának oklevélkritikai vizsgálata” [Source criticism and analysis of the emergence of Slavonia]. Levéltári Közlemények 41 (1970): 223–40.

Jacoby, David. “Rural Exploitation and Market Economy in the Late Medieval Peloponnese.” In Viewing the Morea: Land and People in the Late Medieval Peloponnese, edited by Sharon E.J. Gerstel, 213–76. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 2013.

Janeković-Römer, Zdenka. Višegradski ugovor temelj Dubrovačke Republike [The Visegrád treaty as the foundation of the Republic of Dubrovnik]. Zagreb: Golden Marketing, 2003.

Jékely, Zsombor. “A magyarországi Anjou-kori elit műpártolása” [The patronage of the Angevin elite of Hungary]. In Az Anjou-kor hatalmi elitje, edited by Csukovits Enikő, 291–316. Budapest: Magyar Történelmi Társulat, 2019.

Juhász, Ágnes. “A raguzai tisztségviselők a XIV. század közepén” [Officers of Dubrovnik in the mid-fourteenth century]. In Középkortörténeti tanulmányok 5, edited by Éva Révész, and Miklós Halmágyi, 41–53. Szeged: Szegedi Középkorász Műhely, 2007.

Juhász, Ágnes. A késő Anjou-kori dalmát és magyar tengeri hajózás az 1381 és 1382-ből származó oklevelek alapján [Dalmatian and Hungarian shipping in the late Angevine Era according to charters from 1381 and 1382]. Szeged: JATE, 2006.

Karbić, Damir, and Suzana Miljan. “Knezovi Zrinski u 14. i 15. stoljeću između staroga i novoga teritorijalnog identiteta” [The Zrinski Counts in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries: Between old and new territorial identity]. In Susreti dviju kultura: Obitelj Zrinski u hrvatskoj i mađarskoj povijesti [Encounters of two cultures: The Zrinski family in Croatian and Hungarian history], edited by Sándor Bene, Zoran Ladić, and Gábor Hausner, 15–43. Zagreb: Matica hrvatska, 2012.

Karbić, Damir. “Horvát főurak, nemesek és a Magyar Korona a kései Árpád-korban és az Anjou királyok idején” [Croatian barons, nobles and the Crown of Hungary in the late Árpádian and the Angevin kings]. In A horvát–magyar együttélés fordulópontjai, edited by Pál Fodor, and Dénes Sokcsevits, 119–25. Budapest: MTA Bölcsészettudományi Kutatóközpont, 2016.

Klaić, Nada, and Ivo Petricioli. Zadar u srednjem vijeku do 1409 [Zadar in the Middle Ages until 1409]. Zadar: Filozofski fakultet, 1976.

Klaić, Vjekoslav. “Hrvatski hercezi i bani za Karla Roberta i Ljudevita I. (1301–1382).” Rad Jugoslavenske akademije znanosti i umjetnosti 142 (1900): 126–218.

Klaić, Vjekoslav. “O knezu Novaku (1368)” [On Count Novak]. Vjesnik Arheološkog muzeja u Zagrebu 4 (1900): 177–80.

Klaić, Vjekoslav. “Admirali ratne mornarice hrvatske godine 1358–1413” [The admirals of the Croatian navy 1358–1413]. Vjestnik Kr. hrvatsko-slavonskogdalmatinskog zemaljskog arkiva 2 (1900): 32–40.

Klaić, Vjekoslav. “Hrvatski bani za Arpadovića. (1102–1301.)” [Bans of Croatia under the Árpáds, 1102–1301]. Arhivski vjestnik kraljevsta hrvatsko-slavonsko-dalmatinskog zemaljskog arkiva 1 (1899): 129–38.

Kolanović, Josip. Šibenik u kasnome srednjem vijeku [Šibenik in the late Middle Ages]. Zagreb: Školska knjiga, 1995.

Kosanović, Ozren. “Potknežin i vikar kao službenici knezova Krčkih u Senju (od 1271. do 1469. godine)” [Vicecounts and vicars as officers of the Counts of Krk in Senj from 1271 until 1469]. Zbornik Odsjeka za povijesne znanosti Zavoda za povijesne i društvene znanosti Hrvatske akademije znanosti i umjetnosti 31 (2013): 1–20.

Kristó, Gyula. A feudális széttagolódás Magyarországon [Feudal territorial division in Hungary]. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, 1979.

Kurcz, Ágnes. A lovagi kultúra Magyarországon a 13–14. században [The culture of chivalry in Hungary in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries]. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, 1988.

Ladić, Zoran. “Last Will: Passport to Heaven. Urban Last Wills from Late Medieval Dalmatia with Special Attention to the Legacies pro remedio animae and ad pias causas.” Zagreb: Srednja Europa, 2012.

Lővei, Pál. “Mittelalterliche Grabdenkmäler in Buda.” In Budapest im Mittelalter. Ausstellungskatalog, edited by Gerd Biegel, 351–65, 527–30, 538. Braunschweig: Braunschweigisches Landesmuseum, 1991.

Lővei, Pál. “Oklevelek, jegyzékek, városok, épületek [könyvismertetések]” [Charters, registers, cities and buildings. (book reviews)]. Művészettörténeti Értesítő 59 (2010) 123–35.

Majnarić, Ivan. “Personal Social and Legal Statuses in Eastern Adriatic Cities: Norms and Practices of Zadar in the Mid-14th Century.” In Towns and Cities of the Croatian Middle Ages: The City and the Newcomers, edited by Irena Benyovsky Latin and Zrinka Pešorda Vardić, 127–45. Zagreb: Hrvatski institut za povijest, 2020.

Mályusz Elemér. “Az izmaelita pénzverőjegyek kérdéséhez” [On the issue of Ishmaelite mint marks]. Budapest régiségei 18 (1958): 301–11.

Mlacović, Dušan. Građani plemići: Pad i uspon rapskoga plemstva [Noble citizens: the decline and rise of the Rab nobility]. Zagreb: Leykam International, 2008.

Mladen Ančić. “Rat kao organizirani društveni pothvat: Zadarski mir kao rezultat rata za Zadar” [War as an organized social undertaking: The Treaty of Zadar as a result of the war for Zadar]. In Zadarski mir: Prekretnica anžuvinskog doba, edited by Mladen Ančić, and Antun Nekić, 39–136. Zadar: Sveučilište u Zadru, 2022.

Morelli, Serena. “Társadalom és hivatalok Dél-Itáliában a 13–15. században” [Society and offices in Southern Italy in from the thirteenth until the fifteenth century]. In Az Anjou-kor hatalmi elitje [The elite of the Angevine era], edited by Enikő Csukovits, 15–40. Budapest: Magyar Történelmi Társulat, 2020.

Novak, Grga. Povijest Splita [The history of Split]. Vol. 1. Split: Matica hrvatska, 1957.

Papp, Róbert. “A Raguza város és I. Lajos magyar király között 1358-ban létrejött megállapodás kapcsán keletkezett oklevelek regesztái” [The summaries of the charters that were issued in connection with the agreement between Dubrovnik and King Louis I of Hungary in 1358]. Belvedere Meridionale 29 (2017): 101–8.

Petti Balbi, Giovanna. “Gli Spinola nel 12° secolo. Nascita di un’aristocrazia urbana.” Atti della Società Ligure di Storia Patria 57 (2017): 5–65.

Popić, Tomislav. “Službenici zadarskoga Velikoga sudbenoga dvora građanskih sporova iz druge polovice 14. stoljeća” [The officials of the Zadar high court of civil disputes in the second half of the fourteenth century]. Acta Histriae 22 (2014): 207–24.

Popić, Tomislav. Krojenje pravde: Zadarsko sudstvo u srednjem vijeku (1358.–1458.) [Tailoring justice: the Zadar judiciary in the Middle Ages (1358–1458)]. Zagreb: Plejada, 2014.

Pór, Antal. De Surdis II. János esztergomi érsek [Archbishop John II de Surdis of Esztergom]. Budapest: Szent István Társulat, 1900.

Pór, Antal. Nagy Lajos: 1326–1382 [Louis the Great 1326–1382]. Budapest: Magyar Történelmi Társulat, 1892.

Raukar, Tomislav. “I fiorentini in Dalmazia nel secolo XIV.” Archivio Storico Italiano 153 (1995): 657–80.

Raukar, Tomislav. “Zadarska trgovina solju u XIV i XV stoljeću” [The salt trade of Zadar in the fourteenth and fifteenth century]. Radovi Filozofskog fakulteta: Odsjek za povijest 7–8 (1970): 19–79.

Šišić, Ferdo. Pregled povijesti hrvatskoga naroda [An overview of the history of the Croatian nation]. Zagreb: Matica hrvatska, 1962.

Skorka, Renáta. “Érdekházasságok, kényszermátkaságok: A dinasztikus megállapodások politikai, gazdasági és jogi jellemzői a 14. századi Magyar Királyságban” [Marriages of convenience, forced marriages: Political, economic and legal features of dynastic arrangements in the fourteenth-century Kingdom of Hungary]. Századok 155 (2021): 1181–208.

Spreti, Vittorio. Enciclopedia storico-nobiliare italiana. Vol. 2. Milano: Ed. Enciclopedia Storico-Nobiliare Italiana, 1929.

Stjepović, Stijepo. “Habitatores et forenses Arbi: Identitet stranaca i doseljenika u srednjovjekovlju” [Habitatores et forenses Arbi: identity of foreigners and settlers in the Middle Ages]. Europa Orientalis 37 (2018): 273–87.

Szakálos, Éva. “A százdi templom XIV. századi falképei” [Fourteenth century murals of the church of Százdi]. In Adalékok a szlovákiai magyarok nyelvéhez és kultúrájához [Contributions on the language and culture of the Hungarians in Slovakia], edited by Judit Gasparics, and Gábor Ruda, 201–15. Pilisvörösvár: Argumentum Kiadó, 2016.

Szőcs, Tibor. “Az Anjou elit kormányzati feladatai” [The role of the Angevin elite in the government]. In Az Anjou-kor hatalmi elitje [The elite of the Angevine era], edited by Enikő Csukovits, 165–88. Budapest: BTK TTI, 2020.

Teke, Zsuzsanna. “Firenzei üzletemberek Magyarországon 1373–1403” [Florentine businessmen in Hungary 1373–1403]. Történelmi Szemle 37 (1995): 139–150.

Virágh, Ágnes. “Egy itáliai krónika interpretációs lehetőségei: a magyar hadi vezetők Domenico da Gravina krónikájában” [Possibilities of interpretation of an Italian chronicle: the Hungarian military leaders in Domenico da Gravina’s chronicle]. Hallgatói Műhelytanulmányok 5 (2021): 159–71.

Vitale, Giuliana. “Nobiltà napoletana dell’età durazzesca.” In La noblesse dans les territoires angevins à la fin du Moyen Âge, edited by Noël Coulet, and Jean-Michel Matz, 363–421. Rome: École Française de Rome, 2000.

Weisz Boglárka. “A szerémi és pécsi kamarák története a kezdetektől a XIV. század második feléig” [The history of the Szerém and Pécs chambers from their beginnings to the second half of the 14th century]. Acta Universitatis Szegediensis: acta historica 130 (2009): 33–53.

Weisz, Boglárka. “Ki volt az első kincstartó? – A kincstartói hivatal története a 14. században” [Who was the first royal treasurer? – The history of the office of royal treasurer in the fourteenth century]. Történelmi Szemle 57 (2015): 527–40.

Wertner, Mór. “Földvári és pataji Zuborok.” Turul 26 (1908): 87–89.

Wertner, Mór. “Az Árpádkori bánok” [The bans of the Árpád era], Századok 43 (1909): 378–415.

Wertner, Mór. “Az esztergomi érsekek családi történetéhez” [To the family history of the archbishops of Esztergom]. Turul 30 (1912): 114–23.

Zsoldos, Attila. “’Egész Szlavónia bánja’” [The ban of whole Slavonia]. In Tanulmányok a középkorról, edited by Tibor Neumann, 271–86. Budapest: Argumentum, 2001.

Zsoldos, Attila. Magyarország világi archontológiája 1000–1301 [The secular archontology of Hungary 1000–1301]. Budapest: História, 2011.

-

1 On the war, see Ančić, “Rat kao organizirani društveni pothvat”; Csukovits, I. (Nagy Lajos), 63–69; Pór, Nagy Lajos, 321–35; Brković, “Ugovor.”

-

2 On the social tensions, see Novak, Povijest Splita, 222; Ančić, “Rat kao organizirani društveni pothvat,” 107–8; Bećir, “Plemstvo,” 135–67.

-

3 On the Árpád era royal policy, see Gál, Dalmatia, 98–116.

-

4 On the role of the prelates in the Árpád era royal policy, see Gál, “Roles.”

-

5 On the development of the institution of ban, see Zsoldos, “Egész Szlavónia”; Klaić, “Hrvatski bani za Arpadovića”; Wertner “Az Árpádkori bánok,”; Kristó, A feudális széttagolódás Magyarországon, 88–90;

-

6 Varasd and Verőce Counties, both south of Drava River, were not part of the Banate of Slavonia until the end of the Middle Ages.

-

7 On the bans of the Maritime Region, see Gál, Dalmatia, 132–33; Klaić, “Hrvatski bani za Arpadovića,” 243; Györffy, “Szlavónia kialakulásának oklevélkritikai vizsgálata,” 238; Šišić, Pregled povijesti hrvatskoga naroda, 242; Kristó, A feudális széttagolódás Magyarországon, 126–27.

-

8 In 1275, John, son of Henry of the Héder kindred and Nicholas son of Stephen of Gutkeled clan held the title of ban of Slavonia together, with the latter ruling Croatia and Dalmatia. In 1290, Paul Šubić took the title of ban of Croatia, governing the Croatian-Dalmatian territories. See Zsoldos, Világi archontológia, 48; Karbić, “Horvát főurak,” 122–25.

-

9 Engel, Világi archontológia, 38–39.

-

10 On the social background, power, and roles of the bans of Croatia-Dalmatia (and Slavonia), see Klaić, “Hrvatski hercezi”; Szőcs, “Az Anjou elit,” 174–75.

-

11 Engel, Világi archontológia, 39.

-

12 Raukar, “Zadarska trgovina,” 24.

-

13 It is possible that Baldasar de Sorba came into contact with the Hungarian king in the period of diplomatic contacts in connection with the Hungarian-Genoese alliance of 1352 or later in connection with the Hungarian-Venetian wars. The possible involvement of Baldasar de Sorba in diplomacy may be indicated by the fact that in the mid-1350s he was acting as an envoy between Genoa, the Genoese colony of Tana in the Crimea, and Venice. On his diplomatic mission, see Bratianu, “Les Vénitiens,” 150–151, 160. On Baldasar de Sorba in general, see Grbavac, “Baltazar de Sorba.”

-

14 Raukar, “Zadarska trgovina,” 25–26.

-

15 Ibid., 26–28.

-