Agricultural Productivity in the Western Borderlands of the Grand Duchy of

Lithuania (Second Half of the Sixteenth Century)

Maciej Kwiatkowski

University of Bialystok

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

ORCID: 0000–0001–8889–8086

Hungarian Historical Review Volume 13 Issue 3 (2024): 431-445 DOI 10.38145/2024.3.431

The purpose of this article is to determine the grain yields in the royal manors of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in the 16th and 17th centuries. The manorial system in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania appeared with the land reform in the mid-16th century (Volok Reform), when the three-field system was introduced here. However, there were far fewer manor farms in Lithuania than in Poland, but they were very large. Most of them produced grain for export based on peasant labor force. The inventories of the royal estates give account on the seed demand and yields of the most important cereals: rye, oats and wheat. The analysis of more than a dozen manors showed varying yields in Lithuanian estates (Grodno Starosty, Brest Ekonomy and Kobrin Ekonomy), which were due to natural environmental conditions, as well as elemental disasters or human activity.

Keywords: grain yield, productivity, 16–17th-century Lithuania, volok reform, manors

Introduction: State of Research

Studies on crop yields in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth have a deep tradition. The most extensive analysis of the productivity of peasant and manorial farms was done by Alina Wawrzyńczyk1 and Leonid Żytkowicz2 over 50 years ago, focusing mainly on royal and church estates in early modern Poland. Other prominent scholars of the economy of early modern Poland have also paid attention to agricultural productivity, including Jerzy Topolski, Andrzej Wyczański, and Stefan Cackowski.3 Piotr Guzowski and Monika Kozłowska-Szyc are also currently pursuing research on the subject.4 The conditions of the agricultural economy in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania have also long remained at the center of research by historians. Most of the scholarship has been devoted to the period of the Volok Reform5 in the second half of the sixteenth century, in particular to the layout of manors and the lists of the duties of serfs.6 Several works also dealt with the efficiency of agriculture in medieval Lithuania. The economics of the Roch demesne (Novogrudok province) and the Trotsinski estate (Brest–Lithuanian province) were analyzed by Rożycka-Glassowa.7 Jozef Ochmanski wrote about the efficiency of the grand ducal economy in the Kobrin ducal estate.8 Also, Stanislaw Kosciałkowski examined the significance of Lithuanian yields, supported by yield estimates made by Antoni Żabko-Potopowicz in selected grand ducal estates in the eighteenth century.9 Thus, the scholarship on the agricultural economy of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and its efficiency are for the most part several decades old. A recent summary of the research was presented by Alina Czapiuk in the 1990s,10 but this research and the various works of secondary literature mentioned by Czapiuk are in need of an update, urging for some comparative focus on similar questions in other regions.

Case Studies: Selection of the Analyzed Area

Though numerous shorter works of secondary literature have been published on the subject, there is still a lack of a more complete work focused on the study of the functioning of the agricultural economy in the second half of the sixteenth century. I neither intend nor claim, in the discussion below, to discuss all aspects of the productivity of Lithuanian agriculture in the Renaissance. I present my findings primarily with the aim of furthering a more nuanced interpretation of the findings of research focusing on regions to the east of the (quite thoroughly studied) Kingdom of Poland. This will make it possible to include further areas in the analysis of the manorial system.

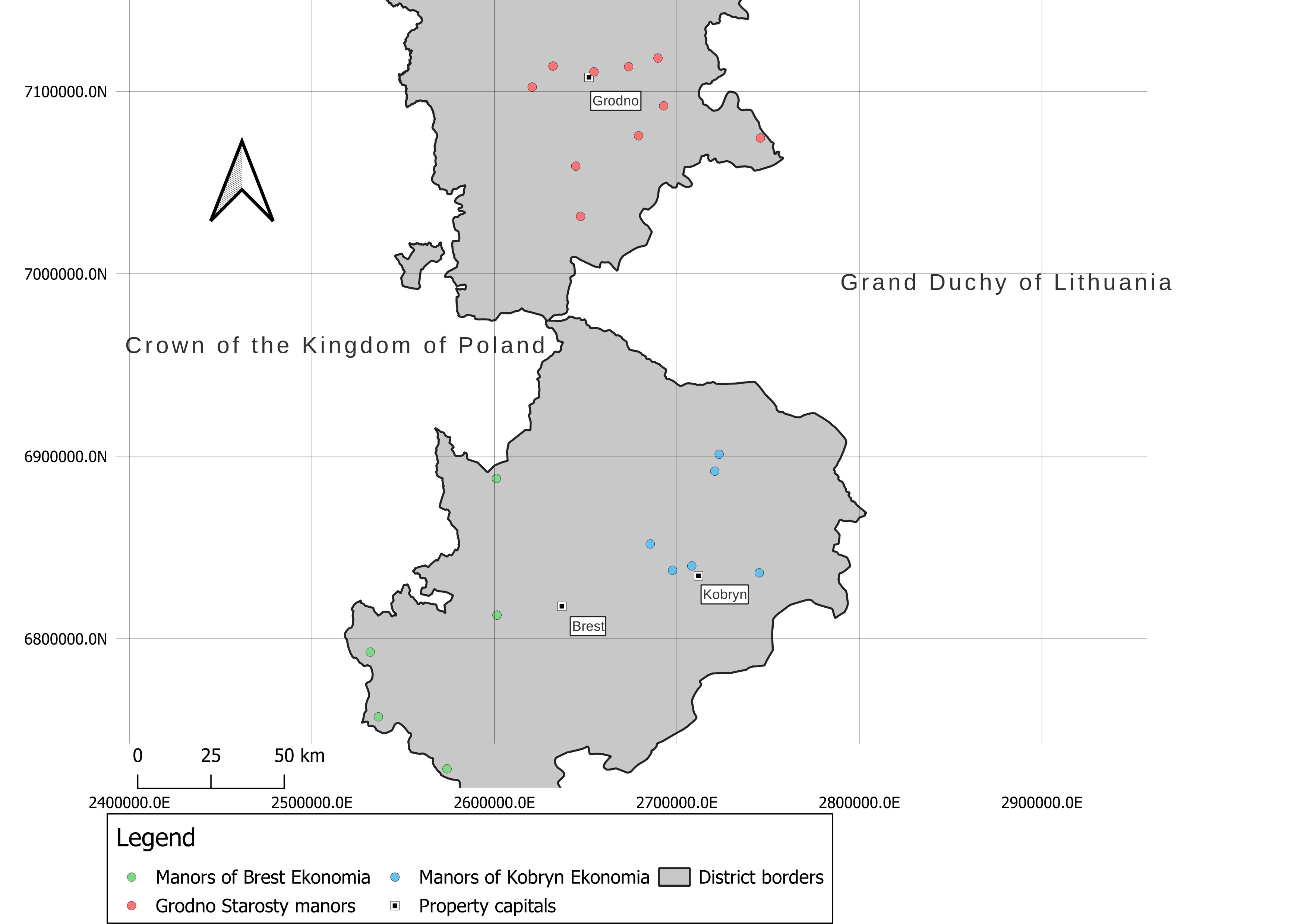

In order to discuss agricultural production in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania from the perspectives of total yield and quality, I focused on three estates as case studies: the Grodno royal estates (1578),11 the Brest royal estates(1588), and the Kobrin royal estates(1597). This selection was not random. In accordance with the 1588 Privilege of Counties on the Table of His Majesty the King, some of the Lithuanian royal (state) properties were transformed into ekonomias, or in other words, they put under the control of the monarch and generated a significant share of the income of the court treasury.12 The existence of Lithuanian ekonomias was confirmed in 1589, and in 1590, in accordance with legislation passed by the parliament the royal table estates in Poland were also separated.13 Ekonomias were usually large estates which included several towns, several manors, and dozens or even hundreds of villages. Sejm acts mention 11 ekonomias. Five of them (Tczew, Malbork, Rogozin, Sandomierz, and Sambor) belonged to Poland, as did the Cracow grand-government and a number of regalia. Another six ekonomias (Brest, Grodno, Kobrin, Mogilev, Olitsa, and Šiauliai) were within Lithuania. Our goal, therefore, was to select relatively extensive areas for the study of relationships on the landlords’ estates.

Map 1. Location of farms in the Grodno Starosty (1578), Brest ekonomia (1588),

and Kobrin ekonomia (1597)

Source: Own compilation based on, AGAD, AK, sign. I/10, pp. 23, 97, 127, 171, 194, 238, 266, 296–297; AGAD, ASK LVI, sign. 11, k. 16, 21v, 24–24v, 28v, 32v–35v; AGAD,

The so-called Lithuanian Metryka, sign. 29, pp. 28, 34–36, 51–52, 71–73, 89–90, 101.

Characteristics of the Sources

Most of the court estates have well-preserved treasury sources from the second half of the sixteenth century. The documents which were drawn up during the period of the Volok Reform, are widely known among scholars.14 The documents offer detailed descriptions of the land, the boundaries of the manors, towns, and villages, and the duties of the serfs, but they reveal little concerning the extent of production on the grand ducal farms. Only inventories from the 1570s and 1590s make it possible to analyze the productivity of manorial farms, in addition to examining a number of duties of the populations living on the estates. The inventories of the Brest and Grodno estates were compiled after the deaths of the previous possessors.15 This is not true in the case of the source on Kobrin’s ekonomia, which was created at the express order of King Sigismund III Vasa, who did not give any specific reason for his command.16 The estates included in this study were found in the western stretches of Lithuania, in Grodno and Brest-Litovsk Counties.

The Crop Yields

There are two basic methods for examining a farmer’s harvest. The first method involves taking the number of threshed crops and dividing the harvest by the size of the previously sown crop (which gives the yield ratio). Thus, we talk about the ratio of one seed sown to one grain harvested. The methodology requires following rules:

1. The study of the proportion of seeds sown to grain harvested must be limited to individual crop species. Thus, we do not deal with the combined yields of rye and wheat unless, for example, we are interested in the yield of winter cereals, which, however, requires appropriate separation of the data.

2. Analysis must be based on standardized units of bulk measures. If a source only offers information concerning seeds sown counted in threescores17 and information about the harvest as measured in barrels, we are not able to give the yield of a particular crop. However, if we were to break this data down (for instance, to arrive at an approximation of the number of grains in a barrel), then the source might contain useful information concerning the yield per threescore.

The above method has been widely used in historical and contemporary scholarship on agriculture in the Polish and Lithuanian lands. Certainly, one of the great advantages of this methodology is its comparative simplicity, assuming we have reliable data in consistent units of measurement.

Another strategy is to indicate crop yields by presenting yield efficiencies in terms of the number of quintals per hectare. This method forces the historian to calculate older units of bulk and area measurements into modern ones. It is thus more time-consuming, as it requires knowledge of several conversion factors. Unfortunately, it is sometimes completely unreliable if the sources do not indicate the size of a given farm. The aforementioned method is used by scientists analyzing agriculture in Western Europe (for instance), but Polish researchers also do not shy away from using the method of estimating yields in quintals per single hectare.18 Due to the difficulty of determining the acreage of old manor farms, we chose the first method of analysis, showing the yields as a ration of seeds down to grains harvested.

For the analysis, we chose all the manors on each estate: ten on the Grodno Starosty, five on the Brest estate, and six on the Kobrin ekonomia. In the sources provided precise data on crops sown, harvests counted in threescores, and threescore efficiency rates. In accordance with the Volok Law regulating relations on the grand ducal estates, all estates used the system of a barrel of brine, equal to four Cracow bushels.19

Table 1. Average crop values on the Grodno Starosty, Brest and Kobrin ekonomias (1578–97) (yield measured to sown seed)

|

Property |

Winter rye |

Spring rye |

Winter wheat |

Spring wheat |

Barley |

Oats |

Peas |

Buckwheat |

|

Grodno Starosty |

2.7 |

1.2 |

2.5 |

4.6 |

2.8 |

1.9 |

2.6 |

2.0 |

|

Brest Ekonomia |

3.9 |

2.6 |

4.6 |

2.9 |

2.8 |

2.5 |

3 |

1.8 |

|

Kobrin Ekonomia |

2.5 |

1.6 |

1.2 |

0.3 |

2.7 |

2.1 |

2.6 |

2.5 |

|

Source: Own compilation based on, AGAD, AK, sign. I/10, pp. 23, 97, 127, 171, 194, 238, 266, 296–297; AGAD, ASK LVI, sign. 11, k. 16, 21v, 24–24v, 28v, 32v–35v; AGAD, |

||||||||

The Table 1 shows the arithmetic average yield on the Grodno Starosty and the manors on the Brest and Kobrin estates in the second half of the sixteenth century. The data suggests that spring wheat was one of the most successful crops on the Grodno estate. In practice, however, this crop was grown on only one grange of the Grodno estate, which in principle excludes the sense of including data on average yields. The data for winter wheat on the Brest estate were identical, although this crop was only grown the farms belonging to three landlords. Quite good values were generated by winter rye on the Brest ekonomia, which usually boasted the best indicators of manor management efficiency. The weakest yield parameters were obtained by spring rye and oats, the average figures for which, as a ratio of grains harvested to seeds sown, ranged from 1.2 to 2.6 and from 1.9 to 2.5, respectively. A comparison of average yield values on these estates to average yields shows that in most cases the Lithuanian estates were not nearly as productive or efficient as the estates in Poland, for example, where the corresponding figures were 3.2–5 for rye, 4.3–7.6 for wheat, 4.5–8 for barley and 1.8–7 for oat.. The averages for the harvests on the grand ducal estates better resemble the yields obtained in Ducal Prussia (rye: 3.5; wheat: 5; barley: 4; oats: 2.8). 20 In comparison with Poland and Prussia, wheat did not fare nearly as well, achieving a similar average only on the Brest economy. Yields were much lower on the other estates, reaching just over one to about 2.5 grains per seed sown.

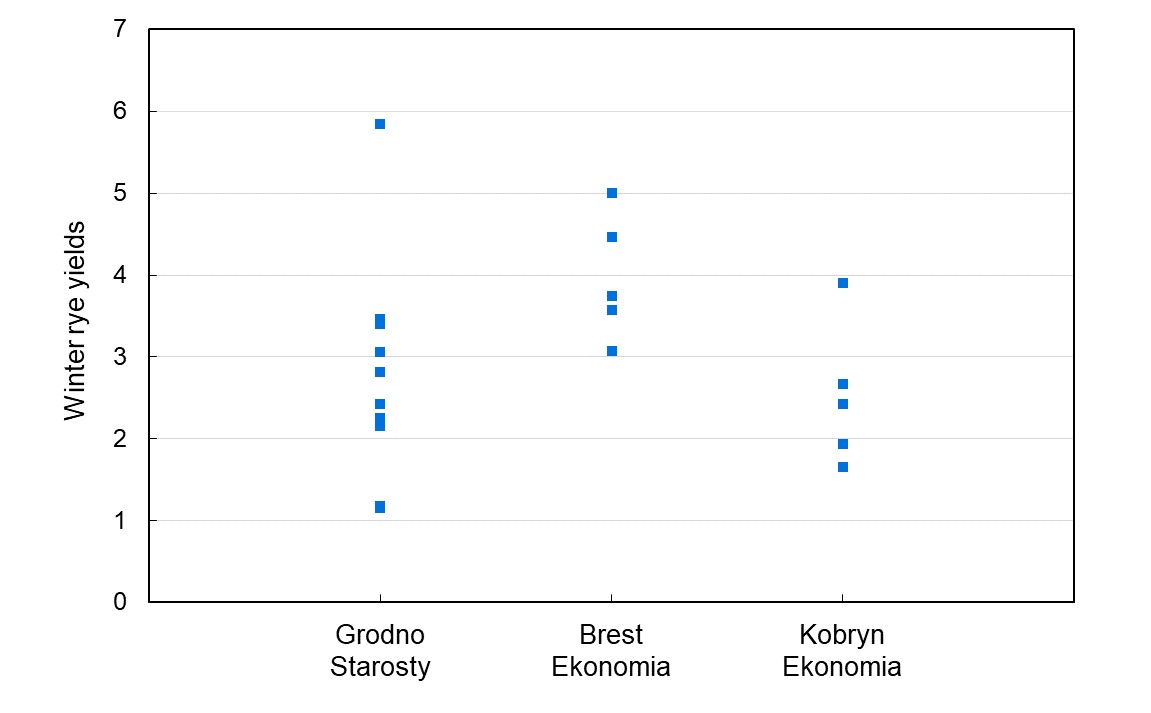

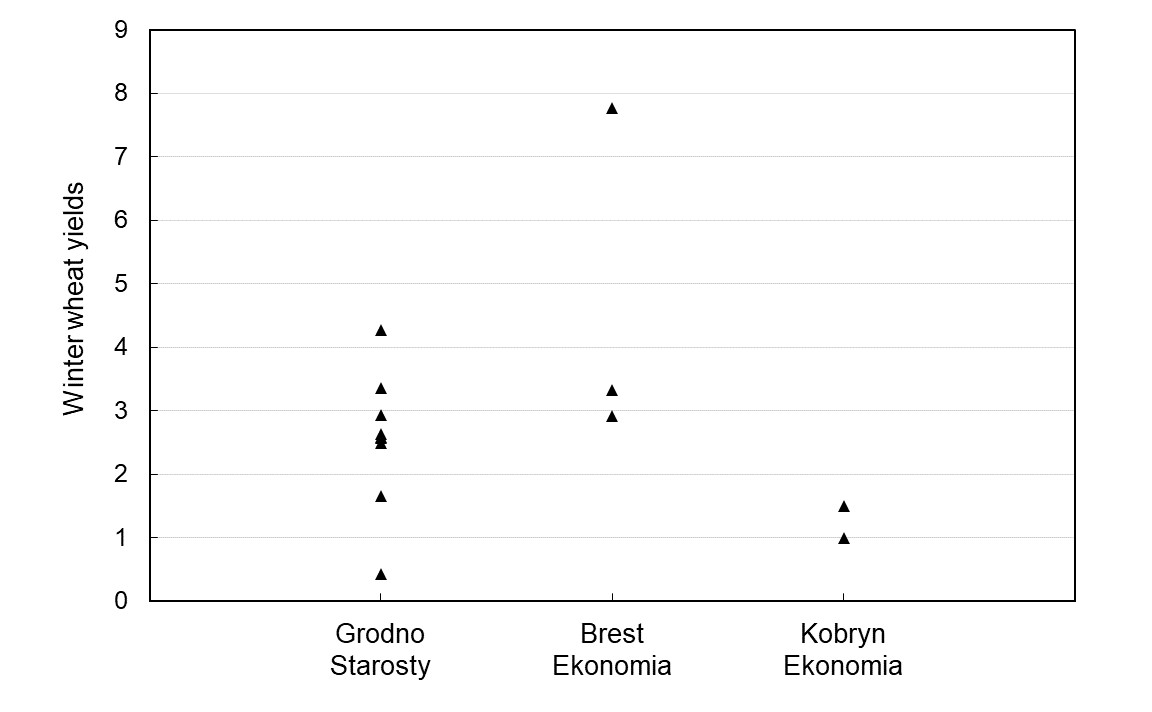

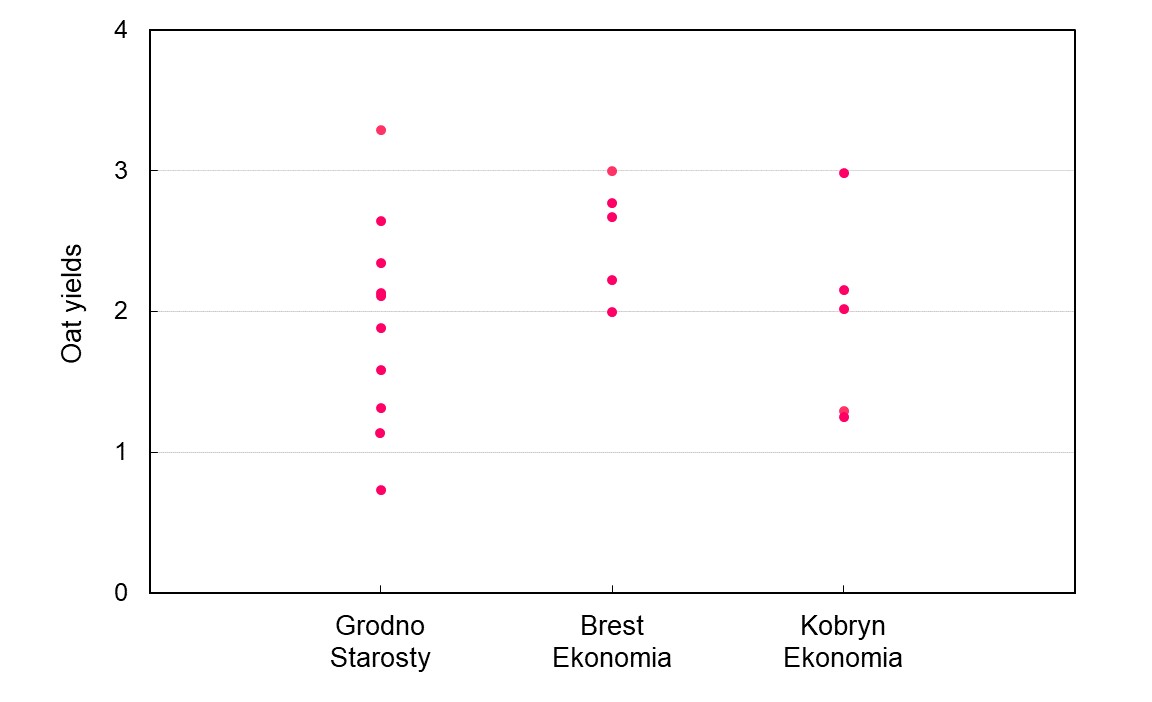

Figure 1. Variability of yields of winter rye, winter wheat, barley, and oats on the Grodno Starosty, Brest ekonomia and Kobrin ekonomia (1578–97)

Source: Own compilation based on, AGAD, AK, sign. I/10, pp. 23, 97, 127, 171, 194, 238, 266, 296–297; AGAD, ASK LVI, sign. 11, k. 16, 21v, 24–24v, 28v, 32v–35v; AGAD,

The so-called Lithuanian Metryka, sign. 29, pp. 28, 34–36, 51–52, 71–73, 89–90, 101.

In addition to indicating the average yield, it would be worth considering the variety of parameters obtained. To this end, one could approach the issue from a comparative discussion of data concerning the yields of four of the most important crops: winter rye, winter wheat, barley, and oats. The focus on these four crops is dictated by two factors: they achieved the highest yields among grains and these regularly appeared in the farm accounts.

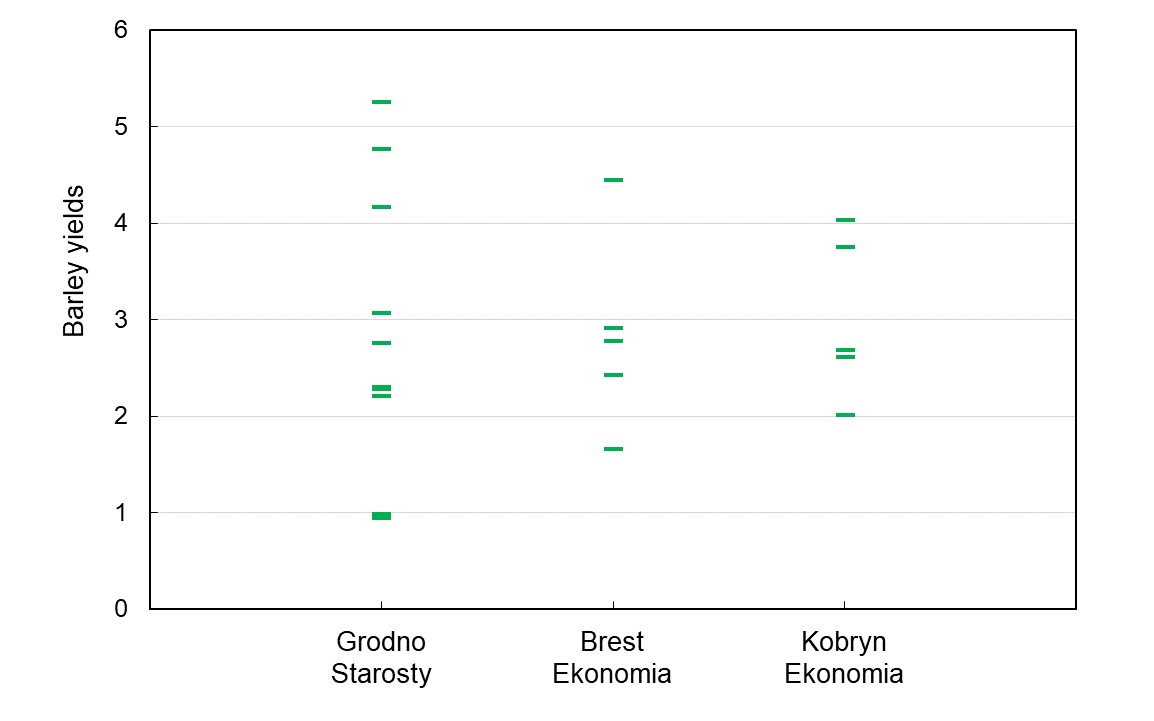

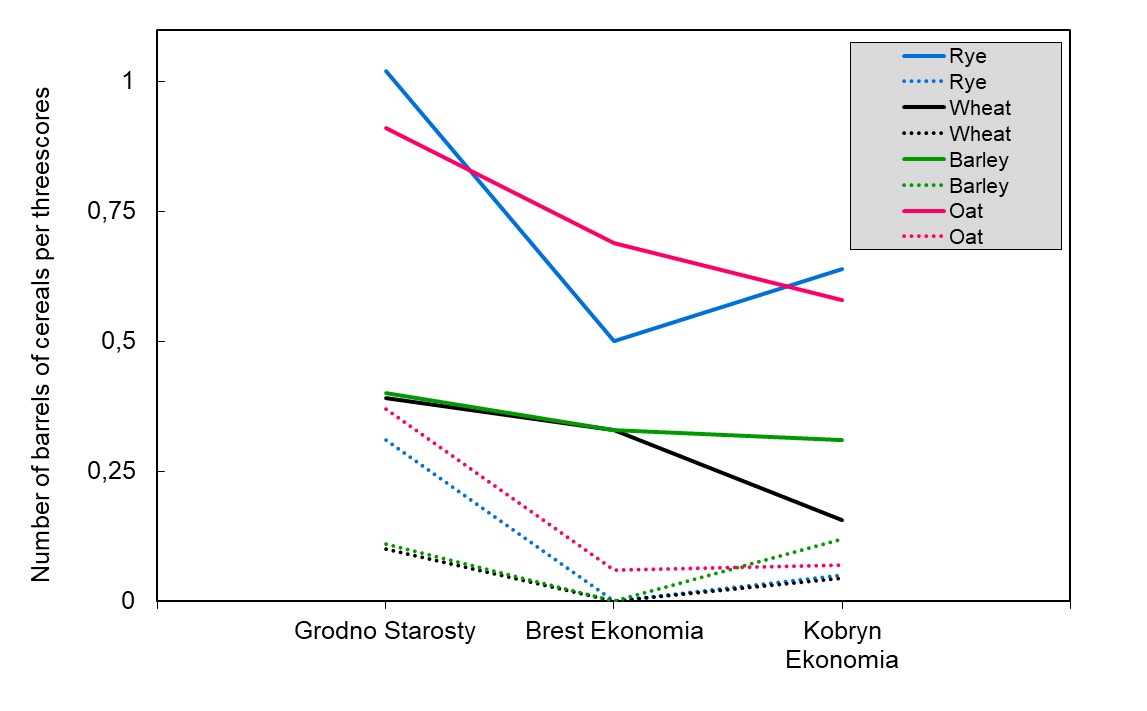

Figure 2. Productivity of crops on the farms of Grodno Starosty and the Brest and Kobrin ekonomias (1578–97) in barrels/threescore. Average values are indicated by a solid line, and the standard deviation by a dashed line.

Source: Own compilation based on, AGAD, AK, sign. I/10, pp. 23, 97, 127, 171, 194, 238, 266, 296–297; AGAD, ASK LVI, sign. 11, k. 16, 21v, 24–24v, 28v, 32v–35v; AGAD,

The so-called Lithuanian Metryka, sign. 29, pp. 28, 34–36, 51–52, 71–73, 89–90, 101.

Fluctuations in yields are evident throughout the study of any selected crops. Only some manors achieved similar yield values, which clearly escape us when focusing only on average grain yields. We see the greatest differences in yields in the case of the manors of Grodno Starosty, which could be due to the larger number of farms owned by lords and not the king. The condition of crops on some of the grand ducal farms presents a remarkably unfavorable picture. This is evident in the case of particularly poor yields of spring and winter wheat, where the yields sometimes approached the lower limit of profitability.

The reasons for the unevenness of the harvest are quite well explained by an analysis of the treasury sources. In 1578, the Grodno Starosty was plagued by hailstorms and fires in selected villages. It is likely that the recorded drought was indirectly responsible for the fires, such under such circumstances, a moment of carelessness with fire would have been enough for buildings to start burning quite quickly.21 The mention in the records of uprooted garden crops also suggest drought conditions (though it is not known whether these crops were uprooted as a result of human activity), but there are other direct references to the disastrous yields too. Usually, lower yields occurred on manors where the records also indicate unfavourable weather events (Horodnica, Mosty).22

Let us take a look at how the efficiency of a single, threshed threescore of crops presented itself. As with the first chart, the target of the analysis will be winter varieties of rye, wheat, barley, and oats.

As the survey of the west-Lithuanian estates indicates, the maximum results were obtained for winter rye and oat crops. If we look at the average yield of a single mound of individual crops, it becomes clear that the highest yields were obtained on the Grodno estate. Simultaneously, the Grodno estate had the most varied crop threshing parameters. The average threshing rates per threescore oscillated around one barrel of brine. The crop yields were smaller on the Brest and Kobrin ekonomias. Barley and oat yields were similar. On average, barley and oat yields were noticeably better ion the Grodno estates and worse on the other estates. The threescore yield on the Brest ekonomia showed variation only in the case of oats. The poor values of threescore of wheat are confirmed in the source dedicated to the Kobrin property, where a very bad wheat yield is mentioned.23 The accounts of the Kobrin ekonomia were also inaccurately kept, since in the case of the Horodec manor we have no data at all on the threshing or yields of rye or oats.24

The agricultural conditions on the estates under discussion were certainly also influenced by the number of livestock. Livestock breeding made it possible not only to obtain meat, hides, and dairy products. Livestock were also used in the fields, for instance in ploughing. In addition, livestock produced a certain amount of fertilizer, which made it possible to achieve higher yields of grain crops. As the sources do not always give a precise record of all the animals on a given manor, I consider only the presence of cows, as the records concerning cows on the estates are more precise.

Table 2. Number of milking cows and heifers on the farms of Grodno Starosty and the Brest and Kobrin ekonomias (1578–96)

|

Estate |

Manor farm |

Number of cows |

Number of cows per |

|

Grodno Starosty |

Horodnica |

6 |

0.6 |

|

Nowy Dwór |

12 |

0.3 |

|

|

Kotra |

11 |

2.7 |

|

|

Odelsk |

0 |

0.0 |

|

|

Skidel |

0 |

0.0 |

|

|

Łabno |

6 |

0.2 |

|

|

Jeziory |

4 |

0.3 |

|

|

Sałaty |

0 |

0.0 |

|

|

Mosty |

5 |

0.3 |

|

|

Wiercieliszki |

18 |

1.5 |

|

|

Milkowszczyzna |

0 |

0.0 |

|

|

Krynki |

0 |

0.0 |

|

|

Świsłocz |

16 |

1.7 |

|

|

Brestekonomia |

Woin (Wohyń) |

0 |

026 |

|

Kodeniec |

0 |

027 |

|

|

Połowce |

– |

– |

|

|

Kijowiec |

11 |

0.9 |

|

|

Rzeczyca |

– |

– |

|

|

Kobrinekonomia |

Kobryń |

5 |

1.0 |

|

Czerwaczyce |

13 |

2.3 |

|

|

Wieżece (Wieżki) |

6 |

0.2 |

|

|

Prużany |

16 |

0.5 |

|

|

Czachec |

– |

– |

|

|

Horodec |

5 |

1.6 |

|

|

Source: Own work on the basis of AGAD, AK, sygn. I/10, 22, 51, 94, 170, 193, 237, 264, 294, 297; AGAD, ASK LVI, sign. 11, 16, 27; AGAD, Metryka Litewska, sign. 29, 28, 33–36, 50–53, 70, 73, 89–90, 101. |

|||

The recommendations of the Volok Law of 1557, which regulated relations on the estates surveyed, said that each manor should have at least 20 cows. If a lord’s farm did not have that many animals, he was ordered to obtain more by purchase.28 The sources indicate that already by the late 1570s the Grand Duke of Lithuania’s instructions were not being followed. A survey of estates with a certain number of cattle shows that the Grodno estate had an average of 8.5, the Brest ekonomia 3.6, and the Kobrin ekonomia 9 mature cows per farm (Table 2). We should approach the above data with a great deal of caution. The Milkovshchyna, Odelsk, and Skidel manors, which were on the Grodno estate and were leased by the widow of the late Grodno starost and the Vilna voivode, were not included in the survey.29 This certainly contributed to lower average numbers of livestock in the records. Similarly, we should not trust the information from the Brest ekonomia, where we know the number of livestock for only one lord’s farm. However, the number of livestock on the Lithuanian estates was much lower than, for example, on the estates in the neighboring Knyszyn Starosty (Podlasie), where there was an average of 41 cows (milking and barren) per single manor.30 Recalculation of the number of milking and barren cows per Lithuanian volok shows considerable diversity in cattle. Values varied the most on the Grodno Starosty, but because of the single census of the cowshed in the Brest ekonomia, we cannot make a full comparison of livestock on the estates under study.

Conclusion

The above observations call attention to the differences in the crop yields on the farms of the Grodno Starosty and the Brest and Kobrin ekonomias. The best yields were generated by the crops of the Brest property, which usually had better agricultural conditions. Typically, Kobrin’s ekonomia had the least productive harvests. This was probably related to the generally inferior conditions of the estate, as evidenced by the few mentions of wheat fertility or the poor condition of agriculture in 1597. The Grodno Starosty was also plagued by unfavorable natural events that reduced the quality of manor crops. However, there is no need to overestimate the negative effects of weather phenomena that periodically afflicted societies in modern Europe. In the case of some estates, it is likely that crop yields were only recorded in the wake of adverse weather events. However, the results of the study show primarily the inferior efficiency of the manor economy on the estates of Western Lithuania, which clearly differed from the situation in the neighboring Kingdom of Poland. The comparatively low crop yields on the estates discussed above were certainly affected by the low numbers of livestock, resulting not only from robberies suffered by the nobility during the interregnum, but probably also from real shortages in the number of livestock. It would certainly be worthwhile to undertake further research on the efficiency of agriculture on the Grodno Starosty and the Brest and Kobrin ekonomias, as this research would show (at least, the discussion above suggests so) that the farms owned by the landlords continued to produce comparatively poor crop yields.

Archival Sources

Archiwum Główne Akt Dawnych w Warszawie [Central Archives of Historical Records in Warsaw] (AGAD)

Archiwum Kameralne [Chamber Archive] (AK)

Archiwum Skarbu Koronnego [Crown Treasury Archive] (ASK)

Inwentarze starostw [Starost inventories]

Metryka Litewska [Lithuanian Metryka]

Bibliography

Printed sources

Pistsovaia kniga byvshago Pinskago starostva. Sostavlennaia po poveleniiu korolia Sigizmunda Avgusta v 1561–1566 godakh Pinskim i Kobrinskim starostoi Lavrinom Voinoiu (s perevodom na russkii iazyk). Published by Ia. Golovatskiy et al. Vilnius: Syrkina, 1874. = Писцовая книга бывшаго Пинскаго староства. Cоставленная по повелению короля Сигизмунда Августа в 1561–1566 годах Пинским и Кобринским старостой Лаврином Войною (с переводом на русский язык), часть 1, ред. Я. Головацкий et al., Вильна: Топография А. Г. Сыркина, 1874.

Pistsovaia kniga Grodnenskoi ekonomii s pribavleniiami, izdannaia Vilenskoi Komissiei dlia razbora drevnikh aktov. Part 1, published by Ia. Golovatskiy et al. Vilnius: Syrkina, 1881. = Писцовая книга Гродненской экономии с прибавлениями, изданная Виленской Комиссией для разбора древних актов, часть 1, ред. Я. Головацкий et al. Вильна: Топография А. Г. Сыркина, 1881.

Pistsovaia kniga Grodnenskoi ekonomii s pribavleniiami, izdannaia Vilenskoi Komissiei dlia razbora drevnikh aktov. Part 2. Published by Ia. Golovatskiy et al. Vilnius: Syrkina, 1882. = Писцовая книга Гродненской экономии с прибавлениями, изданная Виленской Комиссией для разбора древних актов, част 2, пед. Я. Головацкий et al. Вильна: Топография А. Г. Сыркина, 1882.

Ustawa na wołoki Hospodara Korola Jeho Milosti [Volok law of His Highness, Governor Karol] in Obraz Litwy pod względem jej cywilizacji od czasów najdawniejszych do końca wieku XVIII, edited by J. Jaroszewicz, vol. 2, 229–71. Vilnius: Printing House M. Romm 1844.

Volumina Constitutionum. Vol. 1, 1550–1609. Vol. 2, 1587–1609. Published by Stanisław Grodziski, and Wacław Uruszczak. Warsaw: Sejm Publishing House, 2008.

Secondary literature

Boroda, Krzysztof. Pojemność miar nasypnych w XVI-wiecznej Polsce [Capacity of bulk measures in 16th-century Poland]. Bialystok: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu w Białymstoku, 2023.

Cackowski, Stefan. Gospodarstwo wiejskie w dobrach biskupstwa i kapituły chełmińskiej w XVII–XVIII w. Vol. 2, Gospodarstwo folwarczne i stosunki rynkowe [Rural farming in the estates of the bishopric and the Chełmno Chapter in the 17th–18th centuries. Vol. 2, Farmstead and market relations]. Torun: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, 1963.

Campbell, Bruce M. S., and Overton Mark. “A New Perspective on Medieval and Early Modern Agriculture: Six Centuries of Norfolk Farming c.1250–c.1850.” Past & Present 141, no. 1 (1993): 38–105. doi: 10.1093/past/141.1.38

Cerman, Markus. Villagers and Lords in Eastern Europe, 1300–1800. Basingstoke–New York: Palgrave Macmillian, 2012.

Czapiuk, Anna. “O plonach zbóż w Polsce i Wielkim Księstwie Litewskim w XVI i XVII wieku” [On grain yields in Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in the 16th and 17th centuries]. In Miedzy kulturą a polityką, edited by C. Kuklo, 233–48. Warszaw: Wydawnictwo PWN, 1999.

Czapiuk, Anna. “Uwagi o gospodarce folwarcznej w starostwie knyszyńskim w drugiej połowie XVI.” [Notes on the manor economy in the Knyszyn starosty in the second half of the 16th]. In Studia nad gospodarką, społeczeństwem i rodziną w Europie późnofeudalnej, edited by Jerzy Topolski, and Cezary Kuklo, 131–37. Lublin: Wydawnictwo Lubelskie, 1987.

Czapiuk, Anna. “Reformy agrarne w dobrach królewskich na Podlasiu w XVI wieku na tle ich funkcjonowania” [Agrarian reforms in the royal estates in Podlasie in the 16th century against the background of their functioning]. PhD diss., university, year.

Daunar-Zapolski, Mitrofan. Dzyaystvennaya gazpadarka Velikaga Knyazhestva Litouskago zapy pry Jagelonach. = Даунар-Запольски, Миторфан. Дзяйственная газпадарка Великага Княжества Литоускаго запы пры Ягелонах [Economies of the Grand Duchy Lithuania under Jagiellons]. 2nd ed. Minsk: Беларуская навука, 2009.

Mączak, Antoni. Encyklopedia Historii Gospodarczej Polski do 1945 roku [Encyclopedia of Polish Economic History to 1945]. Vol. 1. Warsaw: Wiedza Powszechna, 1981.

Guzowski, Piotr, and Monika Kozłowska. “Wysokość plonów jako wskaźnik zmian klimatu w okresie staropolskim” [Yields as an indicator of climate change in the old Polish period]. In Natura Homines. Studia z historii środowiskowej, vol 1, Historia-klimat-przyroda: Perspektywa antropocentryczna, edited by Piotr Oliński, Wojciech Piasek, 35–47. Toruń: Wydawnictwo Naukowe UMK 2018.

Jezierski, Andrzej, and Andrzej Wyczański. Historia Polski w liczbach. Vol. 2, Gospodarka [Polish history in numbers. Vol. 2, Economy]. Warsaw: Zakład Wydawnictw Statystycznych, 2006.

Jurkiewicz, Jan. “Czynsz i pańszczyzna w ekonomiach królewskich w Wielkim Księstwie Litewskim w XVII– pierwszej połowie XVIII w.” [Rent and serfdom in royal economies in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in the 17th– first half of the 18th century].In Przemiany w Polsce, Rosji, na Ukrainie, Białorusi i Litwie (druga połowa XVII–pierwsza XVIII w.), edited by Juliusz Bardach, 22–51. Wroclaw: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich, 1991.

Kościałkowski, Stanisław. Antoni Tyzenhauz: Podskarbi nadworny litewski [Antoni Tyzenhauz: Court Treasurer of Lithuania]. Vol. 2. London: Publisher Academic Community of the Stefan Batory University of London, 1971.

Kozłowska-Szyc, Monika. “Wysokość plonów rolnych w dobrach królewskich dawnej Polski w latach 1564–1665” [The amount of agricultural yields in the royal estates of old Poland in the years 1564–1665]. Studia Geohistorica 7 (2019): 17–29. doi: 10.12775/SG.2019.02.

Łożyński, Krzysztof. “Stan gospodarczy włości wielkoksiążęcych w świetle Писковой книги Гродненской экономики” [The economic condition of the grand duke’s domains in light of the Писковой книги Гродненской экономики]. In Kintančios Lietuvos visuomenė: struktūros, veikėjai, idėjos, edited by Olga Mastianica, Virgilijus Pugačiauskas, and Vilma Žaltauskaitė, 96–117. Vilnius: Lietuvos istorijos institutas, 2015.

Ochmański, Jerzy. “Gospodarka folwarczna w dobrach hospodarskich na Kobryńszczyźnie” [Manor economy in the hospodar’s estates in the Kobrin region]. Kwartalnik Historii Kultury Materialnej 6, no. 3 (1958): 365–94.

Picheta, Uladzimer I. Belorussiia I Litva v 15–16 vv. Issledovana po istorii sotsialno-ekonomicheskaia politicheskaia I kulturnaia razvitiia = Пичета, Уладзімер I. Белоруссия и Литва 15–16 вв. Исследована по истории Социально-экономическая Политическая и культурная развития [Belorussia and Lithuania, 15–16th centuries: Studies on the social and economic history, political and cultural development]. Moscow: Издатилетво Академии наук ССР, 1961.

Rożycka-Glassowa, Maria. Gospodarka rolna wielkiej własności w Polsce XVIII wieku [Agricultural economy of large property in Poland of the 18th century]. Wroclaw: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich–Wydawnictwo Polskiej Akademii Nauk, 1964.

Santiago-Caballero, Carlos. “Provincial grain yields in Spain, 1750–2009.” Working Papers in Economic History 12, no. 4 (2012): 1–36.

Topolski, Jerzy. Gospodarstwo wiejskie w dobrach arcybiskupstwa gnieźnieńskiego od XVI do XVIII wieku [Rural household in the estates of the Archbishopric of Gniezno from the 16th to the 18th century]. Poznan: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, 1958.

Wawrzyńczyk, Alina. Gospodarstwo chłopskie w dobrach królewskich na Mazowszu w XVI i na początku XVII wieku [Peasant farm in the royal estates of Mazovia in the 16th and early 17th centuries]. Warsaw: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1962.

Wawrzyńczyk, Alina. “Próba ustalenia wysokości plonu w królewszczyznach województwa sandomierskiego w drugiej połowie XVI i początkach XVII wieku” [An attempt to determine the amount of yield in the royal lands of Sandomierz Province in the second half of the 16th and early 17th centuries]. In Studia z Dziejów Gospodarstwa Wiejskiego, vol. 1, edited by Janina Leskiewicz, 94–178. Wroclaw: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1957.

Wawrzyńczyk, Alina. Studia nad wydajnością produkcji rolnej dóbr królewskich w drugiej połowie XVI wieku [Studies on the agricultural productivity of the royal estates in the second half of the 16th century]. Wrocław: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1974.

Wyczański, Andrzej. “O badaniu plonów zbóż w dawnej Polsce” [On the study of cereal yields in old Poland]. Kwartalnik Historii Kultury Materialnej 16, no 2 (1968): 251–71.

Wyczański, Andrzej. Studia nad gospodarką starostwa korczyńskiego 1500–1660 [Studies on the economy of Korczyna starosty 1500–1660]. Warsaw: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1964.

Żabko-Potopowicz, Antoni. Praca i najemnik w rolnictwie w Wielkim Księstwie Litewskim w wieku osiemnastym na tle ewolucji stosunków w rolnictwie [Labor and mercenary in agriculture in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in the eighteenth century against the background of the evolution of relations in agriculture]. Warsaw: Dom Książki Polskiej, 1929.

Żytkowicz, Leonid. “Plony zbóż w Polsce, Czechach, Na Węgrzech i Słowacji w XI–XVIII w.” [Cereal yields in Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Slovakia in the 11th–18th centuries]. Kwartalnik Historii Kultury Materialnej 18 (1970): 227–53.

Żytkowicz, Leonid. Studia nad wydajnością gospodarstwa wiejskiego na Mazowszu w XVII wieku [Studies on rural farm productivity in Mazovia in the 17th century]. Warsaw: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1969.

-

1 Wawrzyńczyk, “Próba”; Wawrzyńczyk, Gospodarstwo chłopskie; Wawrzyńczyk, Studia nad wydajnością;

-

2 Żytkowicz, Studia; Żytkowicz, “Plony zbóż.”

-

3 Wyczański, Studia nad gospodarką; Wyczański, “O badaniu plonów”; Topolski, Gospodarstwo wiejskie; Cackowski, Gospodarstwo wiejskie.

-

4 Guzowski and Kozłowska, “Wysokość plonów”; Kozłowska-Szyc, “Wysokość.”

-

5 A 16th-century land reform in parts of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (Lithuania proper, Duchy of Samogitia and parts of White Ruthenia). The private initiative was copied by other nobles and the Church, because the reform increased effectiveness of agriculture by establishing a strict three-field system for crop rotation. The land was measured, registered in a cadastre, and divided into voloks (21.38 hectares or 52.8 acres). Volok became the measurement of feudal services (like sessio in the Kingdom of Hungary). The reform was a success in terms of the annual state revenue that quadrupled. In social terms, the reform promoted development of manorialism and fully established serfdom in Lithuania, limiting social mobility. (Remark of the editor)

-

6 Daunar-Zapolski, Dzyastvennaya gazpadarka; Picheta, Belorussiya i Litva; Jurkiewicz, “Czynsz i pańszczyzna”; Łożyński, “Stan gospodarczy.”

-

7 Rożycka-Glassowa, Gospodarka rolna.

-

8 Ochmański, “Gospodarka folwarczna.”

-

9 Żabko-Potopowicz, Praca i najemnik; Kościałkowski, Antoni Tyzenhauz, vol. 2, 62–68. Primarily it concerns the fact that the sources referring to the grand ducal estates form the 1780s provide just lucrum ziaren do intraty, so only the crops that were sold and not all the crops that were harvested.

-

10 Czapiuk, “Uwagi,” 131–37; Czapiuk, “Reformy”; Czapiuk O plonach.”

-

11 The ambiguity of the Grodno estate’s name results from the differences in the printed and archival sources, where both names appear, as well as voloshci grodzieńskie. For the purposes of the discussion here, I use the name of Grodno Starosty, which I presume on the basis of several sources to have been in use in 1578. Golovatskiy et al., Pistsovaya kniga Grodnenskoy, vol. 1, III, 3; Golovatskiy et al., Pistsovaya kniga Grodnenskoy, vol. 2, 25–26; AGAD, AK, sign. I/10, p. 1–3.

-

12 AGAD, AK, sign. I/7, pp. 1–3.

-

13 Volumina Constitutionum, vol. 2,106, 116, 148.

-

14 Golovatskiy et al., Pistsovaya kniga byvshago Pinskago starostva; Golovatskiy et al., Pistsovaya kniga Grodnenskoy, vol. 1, III, 588; Golovatskiy et al., Pistsovaya kniga Grodnenskoy, vol. 2, 25–166.

-

15 AGAD, AK, sign. I/10; AGAD, ASK, LVI, sign. 11.

-

16 AGAD, Metryka Litewska, sign. 29.

-

17 A conversion unit of about 60 sheaves of a given crop.

-

18 Historia Polski w liczbach, 78, 215, 218; Santiago-Caballero, “Provincial grain yields in Spain”; Cerman, Villagers and lords, 101. There are other methods of presenting data on yields, e.g. in bushels per acre. Campbell and Overton, A New Perspective, 70.

-

19 Jaroszewicz, Ustawa na wołoki, 238–39; Encyklopedia Historii Gospodarczej, vol. 1, 344; Boroda, Pojemność miar nasypnych, 24.

-

20 Cerman, Villagers and lords, 96. Rye crop yields were also much lower than in the collations referring to the relatively close Knyszyn Starosty in Podlasie. Czapiuk, “Uwagi,” 135–36.

-

21 AGAD, AK, sign. I/10, p. 27, 28, 31, 97, 180, 239, 258, 299.

-

22 AGAD, AK, sign. I/10, p. 20, 97.

-

23 AGAD, Metryka Litewska, sign. 29, 72.

-

24 AGAD, Metryka Litewska, sign. 29, 101.

-

25 One Lithuanian volok is roughly 21.3 hectares, Ochmański, “Gospodarka folwarczna,” 372.

-

26 The cowshed was ravaged and probably emptied by Mielnik Chamberlain Kasper Dembinski during the 1588 interregnum, AGAD, ASK LVI, sign. 11, 27.

-

27 This property was also ravaged by the Mielnik Chamberlain. AGAD, ASK LVI, sign. 11, 24

-

28 Jaroszewicz, Ustawa na wołoki, 243.

-

29 AGAD, AK, sign. I/10, 1.

-

30 Czapiuk, “Uwagi,” 136–37.