2024_3_Bagdi

The Incomes and Expenditures of Agrarian Family Enterprises in Interwar Hungary*

Róbert Bagdi

University of Debrecen

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Hungarian Historical Review Volume 13 Issue 3 (2024): 471-508 DOI 10.38145/2024.3.471

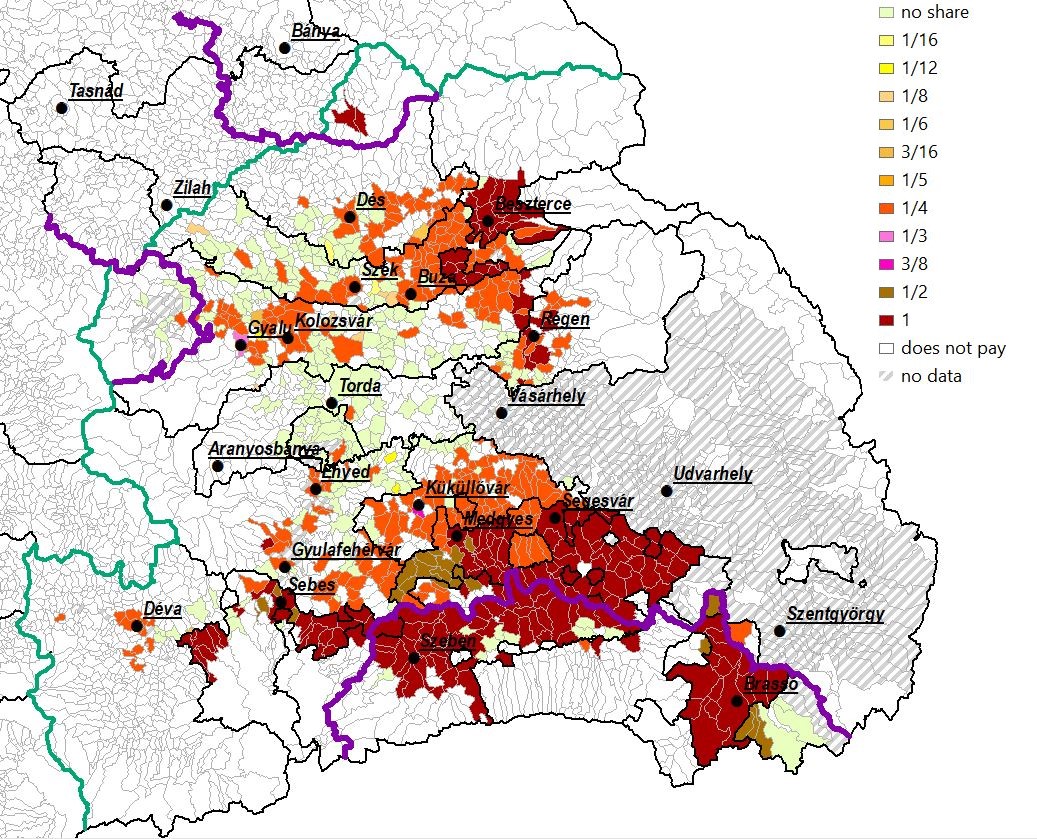

Hungarian statistics in the era of the Dualism and the Interwar period did not go below the settlement level and did not provide any information on the number of livestock and the income from them. Therefore, we do not have exact data on the main problem of the period – whether the large estates or the smallholding showed better yield/ha values, and on the minimum viable size of small farms. Although the movement of ethnographic writers has depicted a dark overview of many settlements, in most cases these do not provide quantifiable data. The surveys organised by the OMGE or the agricultural schools provided statistically relevant quantitative data on certain layers of the peasantry, but the poorest, daily wage-earners remained under-represented in the studies. Therefore, sources that record the incomes and expenditures of these strata in detail (which is the focus of agricultural economists), together with their living conditions (which is the focus of the village researchers’ movement), is particularly valuable. At the University of Debrecen, under the supervision of Rezső Milleker, professor of geography, dozens of theses were written on this topic - though not all of them were conducted according to the professors’ pre-written guidance. In this paper, we try to shed light on the distribution of income and expenditure of the smallholder-peasant class, which was also hit by the recession of the Great Depression, by analysing one of the best, but unpublished work. Beside revenue sources, strategies of survival, techniques of tax-evasion, the profits compared to loan interests are also discussed.

Keywords: smallholders, farm profitability, tax, loans, peasant account books, Interwar Hungary, demographic conditions

Introduction

The events of 1848 can be considered milestones in the development of the Hungarian economy and Hungarian society. Though the war of independence had failed, but dramatic transformations in the legal environment and social relations could no longer be hindered. In the Dualist Era after the Compromise of 1867, the process of modernization accelerated. The transformations also affected the circumstances of those living off agriculture. Serfdom had been abolished, which was a progressive development, but at the same time, the tenants lost most of their leased lands and resources shared with the landlord (common pastures, forests), which fell into the hands of old landlords according to the new laws. The implementation of land redemption in 1848 allowed peasants to become the owners only of their urbarial plots. As a result of this, the multitude of peasants, including those who had not necessarily been poor before, were threatened by impoverishment. Meanwhile, despite general modernization, those who made their living in agriculture continued to live according to the traditional way of life, in some cases even until the mid-twentieth century. As sociologist and former Hungarian Minister of Interior Erdei Ferenc put it, “the peasant social forms remained intact even when the overall structure of society was built on a different principle.”1 According to Erdei, peasants did not adapt to the new market economy in Hungary, because “a peasant farm is not at all a business enterprise designed with commercial rationality, but rather a traditional household farm that operates within traditional frameworks and produces goods. Ultimately, it is incapable of providing surplus for the producer to be sold at the market.”2 This was generally true, though there were exceptions. In the second part of the discussion below, I offer examples of farmers who took the challenges of the new era into account and tried to adapt to a modern (marked-oriented) economy.

On the eve of World War I, most people in Hungary still worked in agriculture. According to István Szabó, based on the data from the 1910 census (recalculated to the postwar area of Hungary), 56 percent were engaged in small-scale farming, including landless agrarian wage laborers and peasants who owned plots of land.3 Due to the polarized estate structure, i.e. the dominance of large estates, the majority of Hungarian society had hardly any land. This threatened the self-subsistence of agrarian families, which had to face the challenge caused by further estate fragmentation.4 These difficulties had accumulated over the decades, and social tensions had intensified. The agrarian movements at the turn of the century, emigration to the United States, and the very limited land reform after World War I were (unsuccessful) responses to these challenges.

The land issue was not resolved between in the interwar period, leaving many questions unanswered. The censuses done by the state and the data gathered in 1941 clearly illustrate the situation of the impoverished who made their living off agriculture. The proportion of those living off agriculture decreased slowly during the interwar period. In 1920, it constituted 55.7 percent of the population. It was still 50 percent in 1940,5 but in absolute terms, the number people working in agriculture had increased.6 In 1930, Hungary’s population density was 93.4 people per km,² making it the eighth most densely populated country in the world at the time.7

According to the censuses, in 1920, 1,212,000 people8 in Hungary lived off agricultural wage labor (meaning that they did not own their own land), and two decades later, their number was still nearly one million (979,000). Considering the general decrease in the number of those living off agriculture, their number as a proportion of the agrarian population did not decrease significantly. Including family members and dependents, this group accounted for nearly two million people. Those with a few hectares of land (a maximum of five hectares, which was the minimum necessary for self-subsistence) were not in a much better position either, and they accounted for nearly one million people.

Another sharp dividing line was drawn between those who owned some amount of land but not enough to subsist on, thus compelling them to search for extra income. In the second half of the twentieth century, historians tried to determine how much land was needed for a family to subsist (this in fact was a key question with political consequences after 1945, when land reforms were initiated to provide plots of a minimum size but still adequate to ensure self-subsistence. Based on Péter Gunst’s work, 9 Gábor Gyáni concluded that a family estate capable of self-sufficiency typically ranged from a minimum of five to ten cadastral acres, depending on the region, crops, and the role of husbandry, and could extend to a maximum of ten to 20 cadastral acres.10 In censuses, however, tracking and defining this thin line between self-subsistence and wage labor is difficult. In the census of 1920, for example, those with ten or fewer cadastral acres were all classified as agricultural laborers, while by 1930, they were referred to as smallholders (likely indicating that they could sustain themselves off their land).11

The work organization of the self-sufficient peasant families fundamentally differed from “wage labor-based capitalist enterprises,”12 as the former’s primary goal was simply to ensure a livelihood. According to Chayanov’s theory of labor-consumption balance,13 the value of the work done by the “self-employed” in self-subsisting peasant economies cannot be expressed in monetary terms, as the results of their productive labor do not enter the market. The peasants only undertook more work when their economic conditions worsened, thus increasing their “self-exploitation” to make a living.14

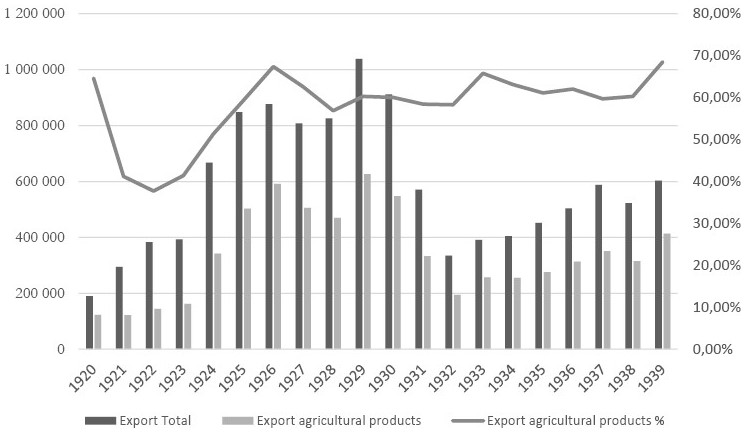

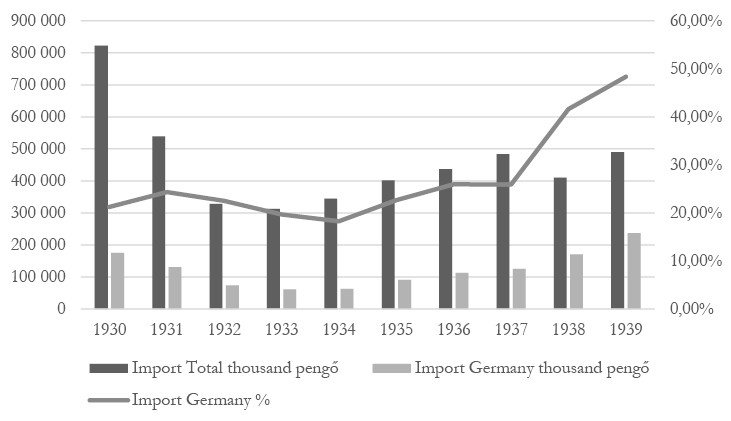

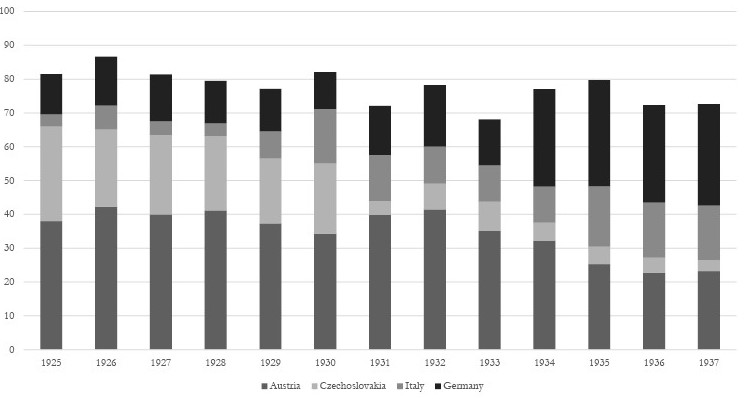

If we look at the macroeconomic environment, during the interwar period, agriculture accounted for about 40 percent of the national income in Hungary.15 At the same time, the difficulties following World War I are well illustrated by the fact that the domestic market consumed only 50–60 percent of agricultural production.16 The rest had to be marketed to foreign countries, which were adopting protectionist tariff policies after the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian common market. In the early 1920s, the agricultural sector ran a debt of 1.3 billion Golden Crowns, which could be estimated at 15 percent of the capital stock. This debt was eliminated with the introduction of the pengő, but in the following years, it reemerged because “the market adaptability of Hungarian agriculture was minimal.”17 The interest rates on loans available to the agricultural sector were around 10 percent, but since “here, the profitability of agriculture only reaches five percent of the invested capital in very exceptional cases, under such circumstances, taking out loans for agriculture can only be unprofitable.”18 The structure of production had hardly changed, as evidenced by the fact that in Hungary, the average yield of wheat had stagnated around 13.8 quintals per hectare even at the outbreak of World War II, while in Germany, there was a 55 percent increase over the course of these two decades.19

Engagement with the “agricultural issue” among experts as well as engagement with marketing problems affecting agriculture began in 1927, when Lajos Juhos20 emphasized in a presentation at the beginning of the year that there was a need for statistical data to formulate future development plans. From December 12, 1927, the National Hungarian Economic Association (Országos Mezőgazdasági Egyesület, OMGE) organized “Farmers’ Days,” when several issues affecting the agricultural sector, generally referred to as the “agricultural crisis,”21 were identified. The decision was made to involve, alongside the Hungarian Royal Central Statistical Office (Központi Statisztikai Hivatal, KSH), the National Hungarian Economic Association and the National Agricultural Business Institute in the collection of agricultural-related data.22 Simultaneously, the examination of peasant farming began along several paths.

At the end of 1927, the OMGE Economic Section was asked to organize data collection. The representative research resulted in a dataset collected from 392 agricultural enterprises, the aggregated results of which were published under the title “The Crisis of Our Agriculture” in 1929 and then reissued in 1930.23 In the 1930s, data collection24 continued, although due to the Great Economic Crisis, the findings were not published for some years.25 I do not provide a detailed overview of the information published by the OMGE regarding the operation of peasant farms. As a single example, let me note that in 1932, the national economic income per cadastral acre on the Hungarian Great Plain for small farms was 85.85 pengő. After deducting labor costs and public charges, a net yield of 9.11 pengő per cadastral acre remained, based on the data from the enterprises examined.26

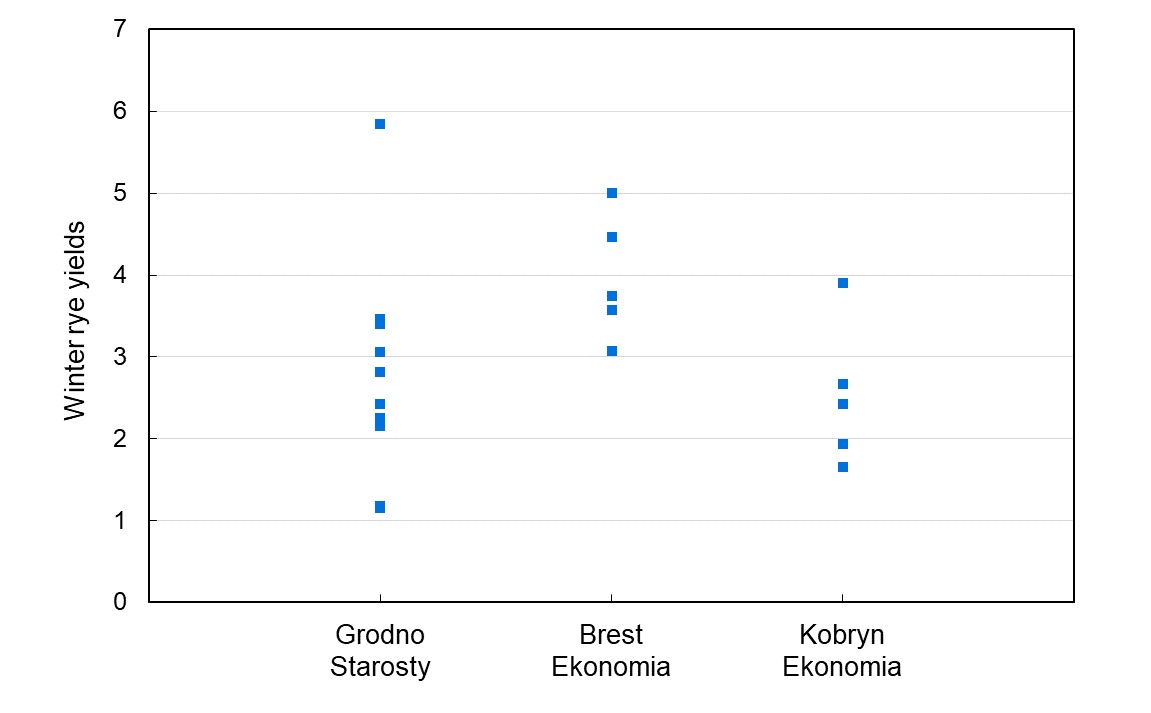

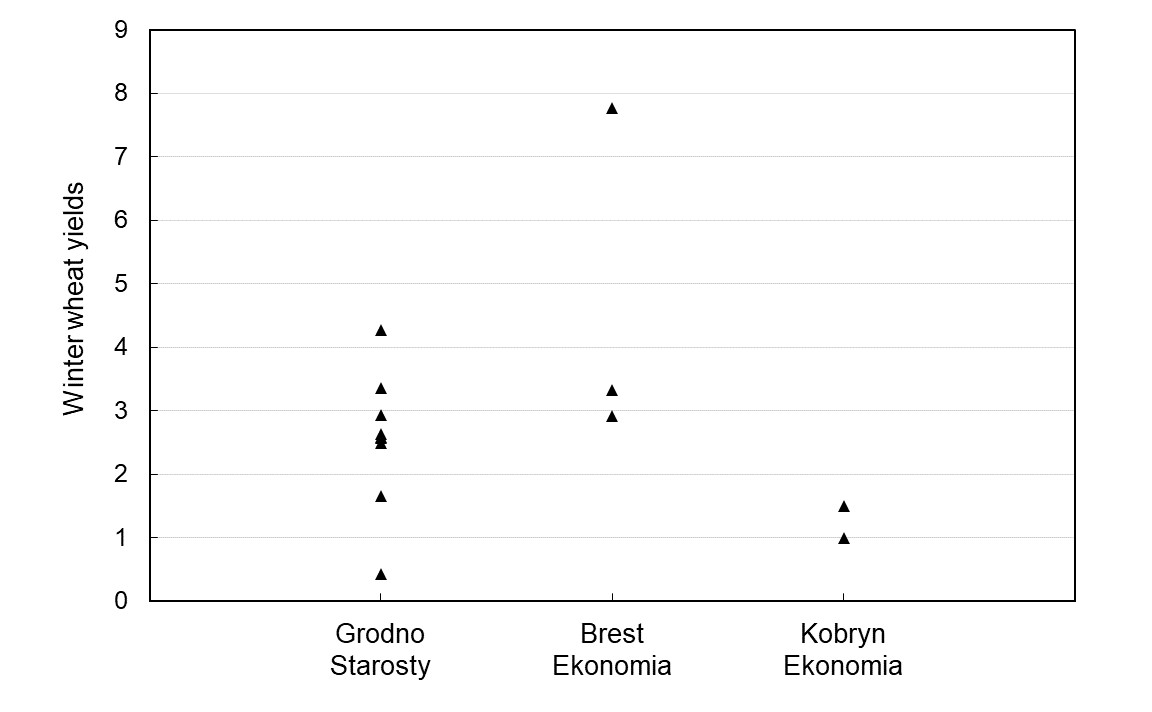

In 1929, the Keszthely Economic Academy was established. The Department of Business Studies of this academy also collected data on “small enterprises.” Of the 126 farms they examined, 60 percent were unprofitable during the crisis years 1931–1932. They could not even cover their operating costs.27 At the Debrecen Economic Academy, Lajos Kesztyűs Sarkadi (1890–1957) prepared detailed statistics concerning the economic results of 100 mainly landowners from the Trans-Tisza region. In in 1931, data from 15 farms (with a size of 50–200 cadastral acres) were processed, while in 1932, data from eight farms were analyzed. In 1931, the focus was on farms with sizes between 50 and 100 cadastral acres, where the rounded net income of 40 pengős corresponded to an interest rate of 3.13 percent. Compared to a bank interest rate of five percent, the interest loss was 1.87 percent. In 1932, typically half of the estates between 100 and 200 cadastral acres ended the year with a net loss based on their operational costs.28 He also noted regarding the farming of smallholders that their average yield of cereals was about two quintals per hectare lower compared to those with 100-200 acres, because they lacked expertise and their soil preparation was weaker. The small landowners were usually mentioned only from a statistical perspective (instead of offering solutions to help them raise yields), which simply meant that those with one or two cadastral acres had very low average yields which negatively impacted the averages of those with less than 100 cadastral acres.29

As a result of the emerging economic crisis, the market positions of agriculture deteriorated. If we consider the price index in 1929 as 100, by 1933, it had decreased to 62.30 In the case of wheat, which was the most important cereal crop, the price index fell from 100 units in 1913 to 77 in 1932, and by 1934, it had dropped to 41 units.31 By 1932, 49 percent of farms and 36 percent of land was indebted, with a debt service consuming 60 percent of revenue.32 In 1931, for properties up to five cadastral acres, the value of debt per acre was 45 pengő.33 Thus, the costs of servicing consumed 88 percent of the profits.34

Ultimately, in the interwar period, the standard of living of the agrarian population stagnated compared to 1913, while during the years of the economic crisis, it declined.35

Research Objectives, Sources, and the Framework of the Investigation

The aim of this study is to illustrate, based on the examples of small farms on the outskirts of Törökszentmiklós during the crisis years of the 1930s, how the economies of smallholder families developed, with particular attention to their financial situation. Relevant sources are scarce, as the census data from the Dualist era did no go below settlement-level to inquire into the financial circumstances of families.36 The aforementioned István Szabó was referring to the decades preceding World War I when he wrote that “based on written sources, it is easier to follow and understand the economic management of a serf from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries than, for example, that of a peasant landowner from the 1860s–80s.”37 We can consider his findings valid for the poor peasant layer in interwar Hungary too, as research focusing on the circumstances of the history of the peasants has hardly dealt with quantitative data at a finer resolution than the settlement level.38 The peasant way of living usually did not include a detailed family “account book” over the course of a year, and statistical data were still not available below settlement level (however, the categorization of land size became more sophisticated).

In the country of “three million beggars” (as interwar Hungary has been called), beside the official statistics and abovementioned institutions and associations, the so-called village research movement also tried to portray the everyday lives of the common people in their numerous publications, but the active members of this movement did so in a qualitative rather than a quantitative way. The ethnographer Edit Fél attempted to use such sources to illustrate the everyday life of an extended family consisting of 14 people in Marcelháza (now in Slovakia), but incomes were not expressed in strictly financial terms.39 None of the village researchers relied on detailed income data or expenditures in their published works when mentioning the problems of village life.

Alongside the well-known works of Géza Féja, Zoltán Szabó, and Imre Kovács, a special yet largely unevaluated series of investigations was initiated by Professor Rezső Milleker (1887–1945),40 the founder of the Geography Institute at the University of Debrecen.41 He encouraged his students “to go into the field” (usually to their birthplaces) to record the circumstances of “typical” families, including financial data and material aspects. For the students’ benefit, a questionnaire was even created, yet despite this, the essays written by the students to complete their degrees had very heterogeneous structures.42 Several of them did not provide any numerical data at all, while others focused on ethnographic or physical and geographical descriptions or merely presented descriptions of the circumstances and lifestyle of a single family. Among the remaining essays, the one that most closely followed Milleker’s written instructions was the work titled “The Types of Economic Farms of Pusztaszakállas” by Károly Molnár, who completed his university studies in 1933.43 After graduation, Molnár taught for a few years (1936–1939) in his native village at the local boys’ school.44 In 1937, a printed version of his speech titled “The Good Student and the Good Pupil” was published in the local school bulletin.

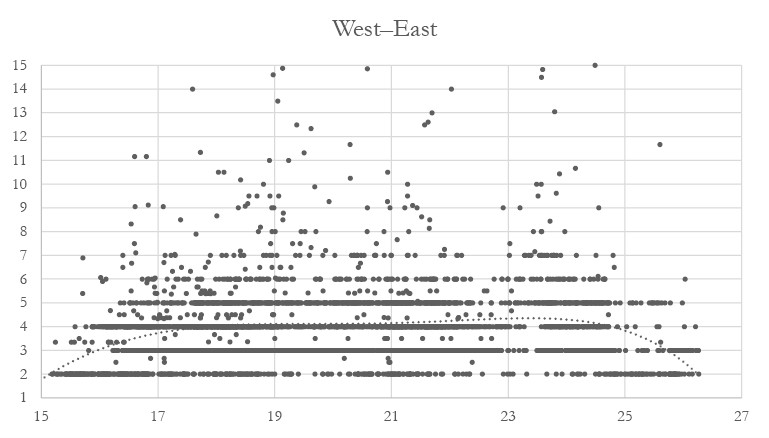

Pusztaszakállas lies on the outskirts of Törökszentmiklós. In 1930, the town had an area of 53,000 cadastral acres, including several outlying inhabited areas (so-called “tanyák” or farmsteads),45 including Pusztaszakállas. The population of Törökszentmiklós in 1930 was 28,503, 12,371 of whom lived on the outskirts, accounting for 43.4 percent of the town’s population.46 According to Molnár, around 1930, Pusztaszakállas47 had a population of only 250 and covered a total area of 3,000 cadastral acres, but half of this was marshlands and swamps along the Tisza River, while the other half consisted of fertile black soil where only potatoes did not thrive.48 In the early 1930s, the settlement consisted of 42 houses (plus a school and a community center) in which 52 families lived.49 The area of the settlement given in cadastral acres was distributed among only 19 landowner families who owned 17 acres, 3.5 acres, 5 acres, 20 acres, 4 acres, 2 acres, 14 acres, 8 acres, 1.5 acres, 4 acres, 2 acres, 13 acres, 30 acres, 6 acres, 1 acres, 5 acres, 1.5 acres, 23 acres, and 180 acres.50 Nine families made a living off fishing, and one person lived in the village as a retired gendarme. A blacksmith, two masons, and three cobblers also lived there, but they too could not make a living solely from their work, so, during the harvest season, they had to take on agricultural wage work.

Land consolidation was not executed in the area. There were no vineyards or orchards at all, and the 750 cadastral acres of pasture was private property and not communal land. In terms of landownership, there was one estate exceeding 500 cadastral acres in Pusztaszakállas, while an additional four individuals owned between 100 and 500 cadastral acres, four individuals had between 50 and 100 cadastral acres, 35 individuals owned between ten and 50 cadastral acres, and 21 individuals had land holdings of less than ten cadastral acres.51

In Törökszentmiklós as a whole, five-sixths of the land was in the hands of large landowners, while “medium and small landowners52 made up a significant portion of the population, but it was rare to find a farmer with 100 acres. The number of veterans’ new plots was five, with 20 acres of land per person.”53 The leadership of Törökszentmiklós consisted of a “representative body made up of 20 large landowners, as well as affluent middle and small landowners and wealthy intellectuals.”54 It is also important to note that Törökszentmiklós had a debt of 1.1 million pengő in the mid-1930s, which significantly affected both sides of the budget.55 In order to balance the municipality’s budget, a 21 percent municipal surtax56 and a three percent emergency surtax were imposed in 1932, and by 1933, the rate of the municipal surtax had risen to 49 percent.57

According to Zsolt Szilágyi’s calculations, Törökszentmiklós was considered a “market sub-center” in the interwar period, as it remained in the “shadow” of Szolnok. In practice, this meant that the town was unable to attract residents from other settlements beyond its own population.58 Lajos Tímár defined the settlement as a “rural market town.”59

Family Types in Pusztaszakállas

1932, the year in which Molnár pursued his research year, represented the economic low point of the ten years between 1929 and 1938.60 In his unpublished thesis, Molnár identified six different family types in Pusztaszakállas, but he did not clarify the criteria he used to select the families presented, thus depriving future generations of the opportunity to determine through further research whether the selected six families represent the local society correctly. It seems that the size of the family, the amount of land they owned (even if only a small amount), their ages, and their farming practices all played a significant role in his classifications.

The families from Pusztaszakállas included by Molnár in his discussion owned a certain amount of land. The average size of the lands owned by the 19 families was 17.9 cadastral acres. If one excludes the landowner with the ‘extreme’ 180 cadastral acres (none of the six different types presented could have owned this much land), the average size decreases to 8.9 cadastral acres. Based on Molnár’s descriptions, we do not need to consider anyone with a landholding larger than ten cadastral acres (when they owned more land than this, farmers tended to employ agricultural labor, at least during the agricultural “high season,” but there is no indication of this in the descriptions). This leaves us with only twelve small landowners, whose average property size was merely 3.6 cadastral acres. The six families under discussion constituted 50 percent of them and thus represent this subgroup.

Demographers evaluate the “developmental cycle” of a family as a process of continuous change, since along with advancing age, births, deaths, and migrations also modify the structure of the family.61 A key factor in Chayanov’s theory regarding peasant economies is the number and composition of the members of a household. He calculated that in the case of marriages, a child reaching adulthood was born every three years, resulting in increasingly deteriorating living conditions during the first 14 years. From the age of 15, the firstborn child could be considered an asset as someone who could be part of the household workforce. Thus, the ratio of dependents began to decrease.62 Molnár very was probably not familiar with this theory, but he did take age into consideration, as he introduced, for example, “young married couples” who were just starting their careers, as well as couples over 70 years of age.

If children who had reached adulthood married but remained on the same property as their father, then multiple generations lived together. It was possible to increase the amount and intensity of labor without employing servants, while young people, on the other hand, did not immediately have to face the full burden of independent life.63 If we consider the long-term changes in household structure, there was a national trend indicating that in the nineteenth century, household sizes increased, followed by a rapid decline starting in the early twentieth century.64 Molnár’s research also confirms Faragó’s general statistical observation that large families were also disappearing in Pusztaszakállas.

A Large Family with a Small Estate (Type I)

Molnár did not provide any supporting points or other references regarding the family he referred to as Type I, nor did he clarify the basis for its classification. Based on the narrative description, it seems that (using Laslett’s typology) the two-generation extended family was the decisive factor here. The 54-year-old farmer had seven children, three of whom were already married when the data was collected. Among them, his 28-year-old son lived with his wife in the same household as his father. Their house had a thatched roof and two rooms and a kitchen, but Molnár was unable to provide the exact floor area of the house. One of the rooms was 6 × 4.5 × 3 meters in size. Five people slept in this room. During the summer, the farmer and his two younger sons slept in the barn. With regards to the buildings used for farm work, there was a stable, a pigsty, a barn, and a beehive. According to Molnár, however, the farmer did not understand beekeeping.65

The family had six cadastral acres of land and one cadastral acre of meadow. The most complex “budget” was provided in this case, so I have organized the data in tables. Molnár paid attention in his essay to high taxes in the case of each family type examined. In the case of the first type, however, even the taxes levied under different titles were given in detail (Table 3).

The family had 46 fruit trees (which bore apples, plums, and walnuts), and they consumed the fruit themselves. Their meals were not regular. They ate what they could produce, typically potatoes. One of their winter dinners, for example, consisted of bread and onions, which they salted or dipped in vinegar. They didn’t engage much with culture. Their “library” consisted of a psalm-book and a calendar, while the source of information (even concerning public affairs) was not newspapers, but rather their neighbor.66

Table 1. Annual incomes of a large family with small holdings in 1932 pengő

|

I. Growth |

Crop |

Amount |

Unit price (P) |

Total (P) |

|||

|

wheat |

15 quintals (q) |

18 |

270 |

||||

|

barley |

6 q |

11 |

66 |

||||

|

cob of corn |

15 q |

767 |

105 |

||||

|

straw |

32 q |

0,45 |

14,4 |

||||

|

crushed straw |

20 q |

0,5 |

10 |

||||

|

scene |

29 q |

6,5 |

188,5 |

||||

|

carrot |

50 q |

1 |

50 |

||||

|

potato |

4 q |

8 |

32 |

||||

|

Total |

735,9 |

||||||

|

II. Vegetables |

common bean |

15 kg |

0,3 |

4,5 |

|||

|

pea |

5 kg |

0,32 |

1,6 |

||||

|

ground sweet peppers |

4 kg |

3,1 |

12,4 |

||||

|

vegetable (cabbage) |

10 kg |

0,15 |

1,5 |

||||

|

cucumber |

10 kg |

0,2 |

3 |

||||

|

onion |

104 kg |

0,28 |

29,12 |

||||

|

garlic |

2,5 kg |

0,5 |

1,25 |

||||

|

poppy seeds |

3 kg |

0,8 |

2,4 |

||||

|

white cabbage |

40 heads |

0,01 |

0,4 |

||||

|

Total |

56,17 |

||||||

|

III. Livestock |

Animal |

Individuals |

Unit price (P) |

Total |

|||

|

pork |

2 |

40 |

80 |

||||

|

goose |

17 |

7 |

119 |

||||

|

chicken |

48 |

1,8 |

76,8 |

||||

|

Total |

275,8 |

||||||

|

IV. Wage |

Work-related |

Subject |

Unit price (P) |

Total |

|||

|

harvest |

9,8 q wheat |

18 |

176,4 |

||||

|

harvest |

0,85 q barley |

11 |

9,35 |

||||

|

harvest |

2 carts of straw |

6 |

12 |

||||

|

Total |

197,75 |

||||||

|

V. Casual work |

Work-related |

Person |

Occasion |

Total |

|||

|

harvesting potatoes |

3 |

12 days |

36 |

||||

|

harvesting onions |

3 |

5 days |

12 |

||||

|

fish transportation |

3 |

12 times |

96 |

||||

|

Total |

|

144 |

|||||

|

Source: Molnár, “Pusztaszakállas gazdaság-formái.” |

|||||||

The family could not make ends meet solely by cultivating their own land, so the head of the family, along with his two oldest sons, took on day labor jobs, which included assisting in the harvesting of onions and potatoes. In total, they earned 144 pengő from the harvest, receiving a daily income of one pengő for potato68 picking, while for onion picking, they were paid only 80 fillér (one-hundredth of a pengő) per person for one day (Table 1). Based on the data, fish transportation was the most profitable, as it provided a daily allowance of three pengő per person. The published data, however, do not indicate what the weight of the fish that had to be carried was. During the harvest, members of the family also took on work for other farmers, but they were paid in kind,69 receiving nearly ten quintals of grain and two carts of straw, which Molnár valued at a total of 197.5 pengő.70 The value of the crops they produced themselves, from wheat to potatoes, amounted to a total of 735.9 pengő, while the garden vegetables represented only 56.17 pengő. The family gained significant income from the livestock, as they were able to sell geese, chickens, and pigs for a total value of 275.8 pengő71 (Table 1). Geese were the most economically viable animals to raise, as they were able to find food in the wet habitats around them. (Half of the territory of Pusztaszakállas was wetland.) According to the figures provided by Molnár, the family’s total income was 1409.62 pengő in the year under consideration, of which 29.8 percent was made in cash (419.8 P), while the rest was in kind.

The goods necessary for the family’s livelihood could be valued at 713.75 pengő, although this was not all spent as cash because they consumed items that they themselves produced (the data are therefore estimates). The amount spent on animal fodder was practically produced by them, but to reach the 300 bundles of corn stalks, it was necessary to purchase 100 bundles.

Table 2. Daily consumption of a large family with smallholdings and expenses necessary for the operation of a farm in 1932 (in pengő)

|

I. Consumption |

Product |

Amount |

Unit price |

Total (P) |

|

flour |

1,050 kg |

0.4 |

420 |

|

|

meat |

60 kg |

1.3 |

78 |

|

|

bacon |

20 kg |

1.8 |

36 |

|

|

fat |

25 kg |

1.8 |

45 |

|

|

sausage |

5 kg |

1.8 |

9 |

|

|

white sausage |

5 kg |

1 |

5 |

|

|

chicken |

30 pieces |

1.6 |

48 |

|

|

fish |

10 kg |

0.8 |

8 |

|

|

egg |

100 units |

0.08 |

8 |

|

|

kitchen garden produce |

56.17 |

|||

|

Total |

713.17 |

|||

|

II. Livestock |

Product |

Amount |

Unit price |

Total |

|

scene |

29 q |

6.5 |

188.5 |

|

|

corn |

15 q |

7 |

105 |

|

|

carrot |

50 q |

1 |

50 |

|

|

miller’s bran |

3.45 q |

13 |

44.85 |

|

|

crushed straw |

20 q |

0.5 |

10 |

|

|

corn stalk |

300 bundles |

0.06 |

18 |

|

|

Total |

|

416.35 |

||

|

III. Economic expenditures |

Value |

|||

|

blacksmith work |

25 |

|||

|

bogging work |

15 |

|||

|

2 large ropes |

8 |

|||

|

1 chain of links |

2 |

|||

|

chimney sweeping |

6 |

|||

|

40 kg of slaked lime |

4 |

|||

|

pasture rent |

46 |

|||

|

40 kg of wheat for the herdsman |

7.2 |

|||

|

to the shepherd |

3.5 |

|||

|

Food for the shepherd for 15 days |

15 |

|||

|

vaccination |

2 |

|||

|

Total |

|

133.7 |

||

|

Source: Molnár, “Pusztaszakállas gazdaság-formái.” |

||||

Their animals were let out to the village’s herd and pigsty, so the herdsman and the swineherd looking after them had to be paid (a total of 25.7 pengő) (Table 2). Several items appeared as expenses for which cash had to be paid, such as sugar, salt, coffee, etc. The salt (Table 3) was not only for meals but also for preserving meat and supplying the livestock’s salt demands. A total of 300 pengő was paid for clothing and footwear. The total amount due for the entire year was 279.58 pengő. The largest item was the tax and loan arrears from the previous year, amounting to 116.56 pengő (41.7 percent), which indicates that tax payments had not been made even in the previous year, and it can be assumed that the figures increased year by year (at least considering the rate of the aforementioned surtax). The land and house tax amounted to 85.39 pengő in 1932 (30.5 percent), while the church tax and the value of public works were both reported as 24 pengő each. This last tax was imposed by the municipality of Törökszentmiklós to finance public works.72

Table 3. Family expenses of a large family with smallholdings in 1932 (in pengő)

|

At Grocer’s |

Product |

Quantity |

Unit price |

Amount |

|

sugar |

10 kg |

1.4 |

14 |

|

|

coffee |

2 kg |

7 |

14 |

|

|

salt |

63 kg |

0.4 |

25.2 |

|

|

pepper |

1.5 kg |

9 |

4.5 |

|

|

acetic acid |

10 liter |

0.4 |

4 |

|

|

lamp glass |

4 pieces |

0.25 |

1 |

|

|

shoe polish |

4 pieces |

0.48 |

1.92 |

|

|

comb |

1 piece |

0.7 |

0.7 |

|

|

kerosene |

26 liter |

0.36 |

9.36 |

|

|

matches |

52 boxes |

0.06 |

3.12 |

|

|

Total |

|

77.8 |

||

|

Clothes |

Product |

Total |

||

|

1 men clothing |

32 |

|||

|

2 pairs men boot |

54 |

|||

|

3 pairs women clothing |

30 |

|||

|

5 pairs women shoes |

75 |

|||

|

2 hats |

12 |

|||

|

1 winter hat |

7 |

|||

|

6 pair men underwear |

36 |

|||

|

6 pair women underwear |

12 |

|||

|

Clothes |

Product |

Total |

||

|

4 pair silk stockings |

12 |

|||

|

4 nightgowns |

7.2 |

|||

|

6 ? scarf? |

15 |

|||

|

12 textile handkerchiefs |

6 |

|||

|

shoes repairs |

2.5 |

|||

|

Total |

|

300.7 |

||

|

Taxes |

Type of taxes |

Amount |

||

|

land and property tax |

85.39 |

|||

|

disability tax |

0.45 |

|||

|

income tax |

19 |

|||

|

road tax |

3.1 |

|||

|

local tax |

2.1 |

|||

|

healthcare tax |

4.98 |

|||

|

public work |

24 |

|||

|

last year’s arrears |

116.56 |

|||

|

church tax |

24 |

|||

|

Total |

|

279.58 |

||

|

Source: Molnár, “Pusztaszakállas gazdaság-formái.” |

||||

Despite the apparent abundance of data, the information available is probably not complete, making it impossible to determine the balance between revenue and expenses accurately. We can assume that the cash actually earned for daily labor and some marketable goods could be used to cover the expenses that had to be paid in cash (e.g. taxes). From the sale of sheep, there was an income of 144 pengő, and the sale of pigs, chickens, and geese generated 275.8 pengő income for the family, totaling 419.8 pengő (Table 1). On the expenditure side, the amount left at the spice shop was 77.8 pengő, and the total spent on clothing was 300.7 pengő, making a combined total of 377.7 pengő. Taxes had to be paid in cash, but their total amount (279.58 pengő) was much higher than the difference between revenues and expenditures, which was just over 40 pengő. This contradiction cannot be definitively resolved based on the available data. The list of agricultural goods produced cannot be considered complete either. The family kept a cow and its calf, but it doesn’t seem likely that they were not able to consume any dairy products over the course of the entire year. The value of the chickens appears in our tables with two different amounts. Those sold were successfully sold at a price of 1.6 pengő each, while for personal consumption their value was determined to be 1.8 pengő. From a consumption perspective, the more than one ton of (reported) flour used annually for baking bread came to less than a half a kilogram of bread per person per day for the eight-member family. This is not much. A hundred eggs per year (i.e. two eggs per family per week), the annual 20 kg of bacon rounded to 7 grams per day, and 8.5 grams of fat were allocated daily per person. Meanwhile, the men spent the summer harvesting and doing other physical work, which required a high daily calory intake. Finally, 63 kg of salt seems excessive for preserving 60 kg of meat. Indeed, it would have been too much for salting the meat, bacon, or the five kg of sausage in the pantry preserved for later consumption. No matter how modest the circumstances of the family were, these low values still seem contradictory or simply implausible.

A Couple without Land (Type II)

It is worth beginning with the summary assessment written by Molnár about an individual classified as Type II: “He does not care much about the past: he did not enjoy better times before, nor will he in the future.” This individual, Molnár implies, lives only for today, and for him, the most important thing is spirits [meaning not holy water but brandy]. He had, at least according to Molnár, neither principles nor culture: “They are the most extreme people in the village and the most uncultured people.”73

A 64-year-old fisherman lived with his wife in their own house, which measured 10 × 3.5 × 2 meters and consisted of three rooms (a living room, a kitchen, and a pantry). The man used a fur coat as a blanket. He did not have an outbuilding for his livestock, so he kept his pig in his room, along with the trough. According to Molnár, the “hygiene was primitive,” as they never bathed and practically never washed themselves and changed their underwear only once a month. Their income situation could be summarized with the simple principle that “[only] God knows what you will live off today and tomorrow,”74 so they ate irregularly and ate whatever they happened to receive or find in the natural world around them. They had few work opportunities. In winter, for example, they sometimes patched socks and repaired shoes for others. Of the labor they performed over the course of the year, only the work they did during the harvest seasons could be quantified, as the man worked 252 hours alongside the threshing machine. However, the time spent on fishing could not be precisely determined. In light of the this, their cash income was low. The largest amount, 128 pengő, came from fishing, but half of the revenue from this had to be paid as a fishing fee. In a year, the man consumed food worth 108 pengő, but this can only be considered a theoretical, calculated value, as he received, exchanged, or “found” most of the products listed here. For food, over the course of the year,75 he paid cash (1.8 pengő) for three kg of mutton. At the spice shop, he spent 11.92 pengő in a year, for example, 3.2 pengő for eight kg of salt, 0.27 pengő a lampshade, and 7.04 pengő for 22 liters of kerosene. He also paid 1.44 pengő for 24 boxes of matches. He carried a debt to the shop of a few pengő all year round. He only spent money on clothing when a given garment was completely worn out. He replaced his shoes every six to seven years, and even then, he only wore them in winter. Thus, over the course of the year, he spent only 10.5 pengő on a total of four pieces of clothing.76

His total income was 123.9 pengő, which he earned from the slaughter and sale of pigs (47.4 P), the sale of 15 chickens (7.5 pengő), patching (5 pengő), and fishing (64 pengő). In total, 116.76 pengő was spent over the year, including rye at 20.9 pengő (17.9 percent), tobacco at 8.84 pengő (7.6 percent), and pálinka (fruit brandy) at 72.8 pengő (62.4 percent), in addition to the items mentioned in the previous paragraph.77

According to the balance published by Molnár, there should have been some pengő left in the farmer’s pocket, but this was not the case in practice, because if he earned any income from patching (which amounted to a total of 5 pengő per year), he immediately bought a larger quantity of fruit brandy. His tax liability amounted to 27.3 pengő, which he tried to manage by paying a third of his annual tax, but he never intended to pay the remaining two-thirds. He did this simply to avoid being harassed by the authorities.

If we want to determine the balance of the revenues and expenditures with scientific rigor, we also encounter contradictions. For example, Molnár did not specify how much the farmer earned from his 252 hours of work next to the threshing machine. We must also assume a lack of information regarding the pig slaughter, as the text mentions an animal weighting 110 kilograms. In the case of pigs, it is necessary to consider that slightly less than half of the live weight should be accounted for as meat. If the owner sold nine kg of bacon, ten kg of fat, and 15 kg of meat, then there must have been at least 30 kg of meat left, which he probably consumed himself with his wife. Thus, he ate not only what he claimed to have found, exchanged, etc. We must assume that the use of eight kg of salt bought from the shop was necessary for the preservation of this amount of meat.

Molnár finally noted that “there are five or six such families with the difference that they are young and have one or two children.”78 The number of children and their ages were not considered decisive factors in determining this type based on this remark. In this context, while the activities of the landowner were listed, the size of the landholding was not mentioned, which is why I consider this couple a possible representative of the class of landless day laborers, even though they were no longer active in the labor market due to their age.

A Couple with a Small Landholding (Type III)

The third type was represented by a 76-year-old farmer regarding whom Molnár remarked that “there are seven families of this type in the village, with the exception that they have children who have already left home.”79 The presence and number of children were therefore not primary factors in the identification of this type. This farmer had five acres of farmland, but he rented them out to someone for half of the harvests, probably due to his age. (The average price of such a smallholding was 853 pengő in the 1930s.)80

The couple lived in a house that was 18 meters long and four meters wide with a ceiling four meters in height. It was built half of stone and half of adobe, with a tiled roof. Several of the surrounding farming buildings were also covered with tiles. Molnár referred to their bathing habits as “rural,” which meant that they washed themselves in cold water every day, while on Sundays they used warm water.81 In terms of their meals, Molnár highlighted caraway seed soup as a frequent item during the day and bread with bacon for dinner. Between 15 and 20 liters of wine were consumed annually, along with an additional five liters of brandy, while tobacco was consumed at a rate of one pack per day, valued at 0.11 pengő per package.

The farmer’s 65-year-old wife cultivated some corn and also kept a vegetable garden measuring a square rod. Molnár was unable to determine the necessary work hours afterwards, but the couple worked on some land for 310 days of the year (but not all day).

Since they did not have children,82 they did not want to adopt a new lifestyle. In terms of their income, the goods obtained from the natural world around them played a significant role.

Table 4. The annual income in pengő in 1932 of a 76-year-old smallholder with five cadastral acres who was no longer actively working

|

Land leased for the half of the products |

Land leased for the third of the products |

|||||||

|

Crop |

Amount |

Unit price (pengő) |

Value (pengő) |

Crop |

Amount |

Unit price (pengő) |

Value (pengő) |

|

|

wheat |

8.1 q |

15 |

121.5 |

corn |

8 q |

4.0 |

32 |

|

|

barley |

4.8 q |

7 |

33.6 |

pumpkin |

24 q |

0.5 |

12 |

|

|

straw |

30.0 q |

1 |

30.0 |

Total |

|

44 |

||

|

Total |

185.1 |

|||||||

|

Source: Molnár, “Pusztaszakállas gazdaság-formái.” |

||||||||

The couple kept poultry (20 hens and 3 roosters) and managed to sell some of the brood and the eggs they produced: 100 chicks for 50 pengő, 70 larger chickens for 74 pengő, and 100 eggs for 28 pengő, for a total of 152 pengő.83 The vegetables grown in the garden were valued at 12.66 pengő, of which only the red onions were sold (two quintals for a total of nine pengő). The cash income was further increased by a calf which the farmer bought and sold on the same day, which generated a profit of 45 pengő.

During the year, items produced by and consumed within the household as internal consumption (flour, meat, bacon, fat, sausage, chicken, eggs) amounted to a total of 352.66 pengő, while at the grocery store, a total of 52.12 pengő was spent on spices, sugar, coffee, salt, pepper, kerosene, etc. Molnár reported a total of 72.2 pengő for clothing expenses, but noted in his list that certain items, such as suits, boots, and hats, were purchased only every two years.84 The clothes were worn until they became unusable, so some pieces of clothing were six or seven years old. For the maintenance of the house, the farmer spent ten pengő in the year examined (three pengő for chimney sweeping, five pengő for plastering and whitewashing, and two pengő for 20 kg of lime)85 (Table 5).

The farmer’s tax book was not available when Molnár visited the community, so the tax amount listed as 20.6 pengő was written into the “accounting records” from memory, but Molnár found the estimated amount to be low. The total cost of pig farming for the entire year was 83.68 pengő for two piglets (their purchase price was 20 pengő, and the rest was spent on feeding them, such as five quintals of barley for 33.6 pengő). Both animals were slaughtered, and their total value was determined to be 140 pengő, although it was not revealed how many kilograms they weighed.86 For the poultry, a cost of 20 pengő was calculated for feeding, while the total value of the day-old chicks, larger chickens, and eggs that were sold was 152 pengő. For personal use, a value of 53 pengő was accounted for from the poultry yard. From the harvested fruit, the farmer was able to sell one and a half hundredweight of apples and plums, which brought in revenue of twelve pengő.

On the income side of the annual revenue, we find 222.76 pengő earned from cultivating the land (185.1 pengő from the farmer’s own land, 34 pengő from a third of the corn, and 3.66 pengő from the vegetable garden). In cash, the actual revenue amounted to 370 pengős (152 pengő from poultry sales; the price of the cow was 140 pengő, “trading” brought in 45 pengő, and the sale of onions, pumpkins, and fruits brought in a total of 33 pengő), which represented 62.4 percent of the total annual revenue.

On the expenditure side, 225.07 pengő were recorded, of which clothing accounted for 72.2 pengő, the total amount spent on purchased tobacco and wine was 46.15 pengő, and taxes were listed as 20.6 pengő87 (Table 5).

Table 5. The balance of annual cash flow in 1932 in pengő for a 76-year-old smallholder with five cadastral acres who was no longer actively working

|

Income |

Value (pengő) |

Rate (percent) |

|

Expenses |

Value (pengő) |

Rate ( percent) |

|

Animal husbandry |

292 |

78.9 |

Clothing |

72.20 |

32.1 |

|

|

Crop production |

33 |

8.9 |

Spices |

56.12 |

24.9 |

|

|

Trade |

45 |

12.2 |

Beverages, for amusement |

46.15 |

20.5 |

|

|

Total |

370 |

100 |

Taxes |

20.6 |

9.2 |

|

|

Animal purchase |

20.0 |

8.9 |

||||

|

Economic expenditures |

10.0 |

4.4 |

||||

|

Total |

225.07 |

100 |

||||

|

Source: Molnár, “Pusztaszakállas gazdaság-formái.” |

||||||

Considering the balance, 144.93 pengő constituted the “remainder.” Behind the seemingly positive balance was the fact that the farmer was saving the money he had brought in by selling the cow because he wanted to buy a new one. Regarding the profit generated by “being the middleman” in the sale of the calf, Molnár noted that the farmer could not make such profits in an average year.

Older Members of Cohabiting Couples from two Generations (“Grandparents”) (Type IV)

Molnár classified a small landowner with four cadastral acres and seven grown children as a member of the fourth type of family. This landowner lived with his wife, and according to “tradition,” the youngest son and his wife lived with him in the same household.88 Molnár provided no textual references that would allow for the identification of other classification criteria. The family members described as type IV lived in a house with a tiled roof measuring 14 × 8 × 3 meters, and they had several outbuildings on their property. We cannot determine the age of the farmer from Molnár’s essay. He probably belonged to an older age group, as his sons were the ones who cultivated the fields.89 He consumed 25 liters of wine at home each year, and he drank about four liters in the pub annually.

The value of the goods produced on their land amounted to a total of 314 pengő. Of the crops, wheat was produced in the largest quantity, 15 quintals valued at 17 pengő each, amounting to a total value of 225 pengő (71.7 percent), of which six quintals were sold (104 pengő). In comparison, the garden vegetables represented a low amount, with the total for vegetables such as green beans, dry beans, peas, cucumbers, red onions, and garlic amounting to 6.05 pengő, and this produce was used by the landowner in the household.

The landowner was only engaged in fishing on a piecework basis. According to Molnár, he devoted 864 hours a year to fishing, which Molnár valued at 140 pengő, calculating it based on 70 days at a rate of 2 pengő per day.90 The family’s total income was 586 pengő, of which 53.6 percent was the value of goods produced in kind, and 46.4 percent was the amount received in cash.

Food items produced and consumed within the household (wheat, corn, fish, potatoes, chicken, eggs and pork) amounted to a value of 297.65 pengő, of which wheat accounted for 119 pengő (40 percent). The landowner spent 27.27 pengő at the spice shop over the course of the year, for example, 4.2 pengő for sugar and twelve pengő for 30 kg of salt. In the list of expenses, Molnár noted that the farmer did not allocate much for clothing, which amounted to the purchase of only two new garments per year: a shirt worth 3.5 pengő and a winter coat worth 70 pengő.91 Among the other costs, taxes were also highlighted, but only the church tax was specifically mentioned, valued at 8.2 pengő, while all other taxes amounted to a total of 80 pengő.92 The landlord owed 150 pengő to the local savings cooperative, which required him to pay 18 pengő annually as “interest.”

In the end, regarding the revenues received in cash, it was possible to report 272 pengő (144 pengő from fishing; 104 pengő from wheat; 24 pengő from poultry), while on the expenditure side, the final amount was similar, 276.44 pengő. Among the cash expenses, the two largest items were taxes, amounting to 95.7 pengő altogether (34.6 percent), and the aforementioned money spent on clothing, which totaled 73.5 pengő (26.6 percent)93 (Table 6).

Table 6. The balance of household cash flow of the older members (“grandparents”) of two-generation cohabiting couples in 1932

|

Revenues |

Value (pengő) |

Rate (percent) |

|

Expenses |

Value (pengő) |

Rate (percent) |

|

Income from fishing |

144 |

52.9 |

Clothing |

73.50 |

29.8 |

|

|

Plant cultivation |

104 |

38.3 |

Taxes |

95.70 |

38.9 |

|

|

Animal husbandry |

24 |

8.8 |

Spice shop |

24.24 |

9.8 |

|

|

Total |

272 |

100 |

Buying a pig |

23.00 |

9.3 |

|

|

Interest on debt |

180 |

7.3 |

||||

|

Radio fee |

120 |

4.9 |

||||

|

Total |

246.44 |

100 |

||||

|

Source: Molnár, “Pusztaszakállas gazdaság-formái.” |

||||||

Nuclear Families Formed by Young Married Couples (Type V)

Type V was represented by a 20-year-old farmer who had two daughters. The farmer was the son of a man described as belonging to the type IV family. Molnár referred to the young age of the farmer twice, so we may assume this was the main aspect of classification.94 He lived with his family in a room measuring 5 × 4 × 2.5 meters, where there was a bed, a mess, and a sofa, but there was no room left for a chair. Molnár noted that their way of life was characterized by “satisfactory hygiene,” as they bathed every day, and in the summer, they swam in the Tisza River. Molnár noted that “they change their underwear weekly.”95 In summer, they ate three times a day, in winter, twice, having some kind of cooked food at noon and bread with bacon in the evening for dinner. They rarely ate fruit. If they did so, it was watermelon that made its way to the table in the summer. The farmer consumed 22 liters of wine in the tavern over the course of the year, along with two liters of brandy. He smoked two packs (at a cost of 0.11 pengő per pack) of tobacco a week. Culture was absent from their lives because “they did not read books or newspapers.”96

In terms of the annual number of hours spent working, the farmer spent 183 hours harvesting, 1200 hours fishing, and 370 hours pressing straw, totaling 1,753 hours of work.97 Molnár specifically noted that from November to March, he engaged in fishing for 112 days and in straw threshing for 42 days, from which he earned 132.8 pengő and 25.2 pengő, respectively. For the work done during the harvest, payment was made in kind, amounting to 5.3 quintals of wheat (valued at 90.1 pengő), 0.24 quintals of barley (3.84 pengő), eight quintals of corn (112 pengő), and 1.5 quintals of potatoes (27 pengő), totaling 232.94 pengő in cash.98 The quantity of cereals was not sufficient for the family, as the farmer had to ask his father-in-law for an additional 270 kilograms of wheat before the harvest. Molnár distinguished the “revenue from livestock” section, where he recorded 30 chickens valued at 60 pengő. Although two lines earlier he noted that some 80–90 chicks had hatched, he only recorded the value in cash for 30. (The remainder were probably consumed by the household). The price was listed as 215 eggs (17.2 pengő), and an additional 300 eggs were used in the household.

The cash income from animal husbandry was 77.2 pengő (the total from selling 215 eggs and 30 chickens at a price of two pengő each). From the garden vegetables (from beans to lettuce), a total value of 23.03 pengő was produced, of which the largest item was one and a half quintals of potatoes, worth 12 pengő.99 A value of 407.83 pengő (for food, such as flour, fat, eggs, bacon, etc.) was consumed (everything was produced on the farm, and he received only 12 kg of fish as a gift). The cost of the feed for the livestock was assessed at 68.88 pengő. In the case of the data provided by Molnár, I would like to point out that the difference between the value of the harvesting wage (232.94 pengő) received in kind and the value of items produced and consumed within the household (407.83 pengő) is represented by the vegetables produced in the garden worth 23.03 pengő, as well as the chicken and eggs consumed, which were worth 141.44 pengő.

In the end, there was a cash income of 248.4 pengő (77.2 pengő from poultry farming; 13.2 pengő from two carts of pumpkins; 132.8 pengő from fishing; and 25.2 pengő from straw pressing). On the expenditure side, a total of 239.2 pengő was spent on spices, clothing, tobacco (13.52 pengő), wine, brandy, and the purchase of a pig (Table 7). At the spice shop, 65.64 pengő was spent, the largest item of which was 30 liters of kerosene, valued at 10.86 pengő.100 The clothing cost a total of 110 pengő in 1931.

Table 7. Annual cash flow of a young married couple (pengő).

|

Revenues |

Value (pengő) |

Rate (percent) |

|

Expenses |

Value (pengő) |

Rate (percent) |

|

Daily wage |

158.0 |

63.6 |

Clothing |

110.0. |

45.9 |

|

|

Animal husbandry |

77.2 |

31.1 |

Spice shop |

65.64 |

27.4 |

|

|

Plant cultivation |

13.2 |

5.3 |

Buying a pig |

31.00 |

13.0 |

|

|

Total |

248.4 |

100 |

Other |

32.72 |

13.7 |

|

|

Total |

239.36 |

100 |

||||

|

Source: Molnár, “Pusztaszakállas gazdaság-formái.” |

||||||

The apparent positive balance is overshadowed by the fact that the farmer owed money to the church (because of the church tax), the amount of which was not even specified. It can be suspected that this amount was higher than the difference between the expenditure and revenue sides of the balance sheet. Despite this, the biggest burden for him was the borrowed wheat he had requested from his father-in-law. As Molnár wrote, “he would want to work more, but job opportunities are quite scarce. … He is generally in a better position than the other poor people in the village, because he knows about fishing and earns quite a bit with it!”101 But Molnár still included the following sobering observation: “They live on a tight budget and rely on parental support.”102

Modern Nuclear Family, Produce Made for the Market (Type VI)

We do not know the age of the farmer described as type VI, only that he participated in World War I and that his son was 18 years old. Molnár stated that he “follows the modern trend,” meaning his goal was to “produce as much as possible in a small space.”103 He began his gardening activities by renting a three-acre floodplain, which he intended to use to grow melons, while planting red onions along the roadside. In the end, it was the onions that brought him profit, which is why he turned to gardening. He was able to start his horticultural business in 1929 by renting eight cadastral acres, and by 1932, he was growing peppers, winter radishes, cabbage, vegetables, and spring onions in hotbeds, where he also implemented motorized irrigation. The family lived a dual life, with the father and son on the land rented on the banks of the Tisza River (in a building they themselves had constructed from clay with a thatched roof), while the female members of the family lived six kilometers away in the village. In Pusztaszakállas, they were essentially the only smallholder family making a profit from farming. According to Molnár, they managed their annual budget data related to horticulture almost perfectly, and this data indicate that they were able to achieve a profit of nearly 2,000 pengő104 (Table 8).

Table 8. The budget of a vegetable producer in Pusztaszakállas in 1932 (pengő)

|

Expenses |

Income |

|||||

|

Item |

Unit price |

Amount |

Item |

Unit price |

Amount |

|

|

8 cad. acres lease |

68 |

544 |

80 q onion |

5.3 |

424 |

|

|

irrigation machine |

800 |

10 carts of cabbage |

15.0 |

150 |

||

|

glass jars (hotbeds) |

154 |

1 cart of radishes |

80 |

|||

|

100 litters of gasoline |

0.24 |

42 |

1 cart of vegetables |

35 |

||

|

8 allocations |

6 |

48 |

85 carts of peppers |

45.0 |

3,825 |

|

|

80 kg onion |

0.5 |

40 |

Total |

4,514 |

||

|

seedlings |

22 |

|||||

|

105 transportation |

3 |

315 |

||||

|

700 casual work |

0.8 |

560 |

||||

|

Total |

2,525 |

|||||

|

Source: Molnár, “Pusztaszakállas gazdaság-formái.” |

||||||

Reviewing the cash flow of the family farm, Molnár noted the costs of transportation (which he estimates to be nearly 400 pengő) and found them high based on the farmer’s account. The irrigation machine represented a greater financial burden, but it was noted that he had three years to pay back the 2,400 pengő expense; and it is likely that this amount had already been paid in the months preceding the data collection. The lease of the land (544 pengő) and the wages of the day laborers also represented significant costs. As a fee, the family paid 0.8 pengő per day. Molnár described this work an easy task that even young girls could handle.105

They made transportation cost-effective by purchasing two horses and transporting their goods to the train station by cart, from where the paprika was sent to Budapest. The vehicle used for transportation was impossible to modify, so they could not even measure how much a shipment weighed. Molnár put it at roughly ten quintals. The family’s success in gardening inspired others in the village, so three people started growing red onions, even though among the vegetable products mentioned so far, onions were the most problematic (for example, harvesting them was considered slow).

The gardener involved in the investigation did not believe that he had to fulfil all his tax obligations, even though he had an annual profit of 2,000 pengő. He chose to declare his activity as arable farming instead of gardening to lower the tax rate.

Summary

How accurate were the data presented by Molnár in his essay? In the 1930s, sociologist Mihály Kerék also dealt with the living conditions of the Hungarian agrarian population. Based on the 96 families living in twelve predominantly lowland working communities he examined in 1932, he found that it was very difficult to make precise determinations concerning their financial situations. The debts were mostly kept track of by the housewives, who were ashamed to declare everything, especially the smaller debts, such as the claims from the grocers. Generally, in the case of occasional jobs as well as for the purchase or sale of smaller items (such as eggs), by the end of the year, they no longer remembered the exact quantities that had been spent.106

Molnár mentions numerous goods (and their monetary values), of which only the price of salt was the same for every family (0.4 pengő per kg). For certain agricultural produce, such as wheat, nearly identical values have been reported (15–18 pengő per quintal). However, there were a few crops or produce items for which the price differences were greater. Barley was valued at 11 pengő per quintal for the Type I family, 7 pengő per quintal for the Type III family, and 16 pengő per quintal for the Type V family. These values were likely determined based on the memories/assessments of the affected families, or there may have been other factors unknown to us. We cannot prove the reasons, but in the case of the mentioned figures, it seems that if someone received half or a third of the crop, its price appears to be low (the mentioned price of barley is 7 pengő per quintal), while the price of the crop received for labour during the harvest seems higher (16 pengő per quintal for barley). For the head of the Type V family, every crop was considered at a high price when he received his payment in kind for his harvesting work: the ear corn was charged at a price of 14 pengő per quintal, and the potatoes at 18 pengő per quintal (the latter, for example, should have cost between five and ten pengő). So there was a great discrepancy between nominal prices and real prices. The difference in the price of red onions is striking: the Type VI family, which produced for the market, received just over 0.05 pengő for each kilogram (this was the wholesale market price, as they were able to sell 80 quintals), while in the case of the Type I family, the more than one quintal produced for personal use was valued at 0.28 pengő per kg (estimated price).

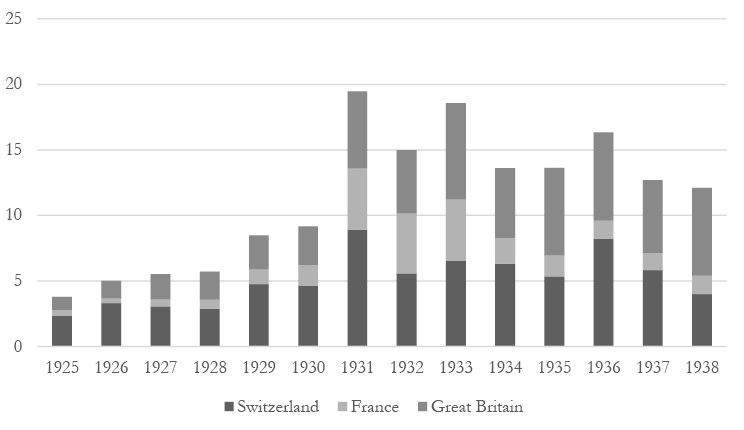

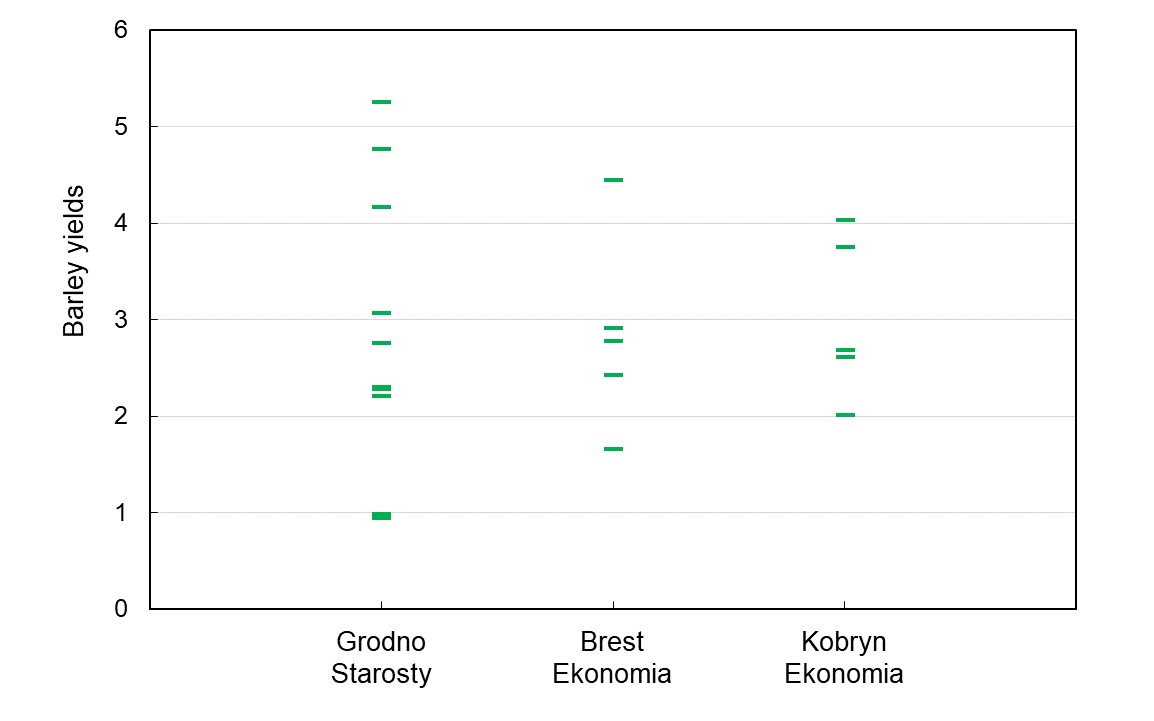

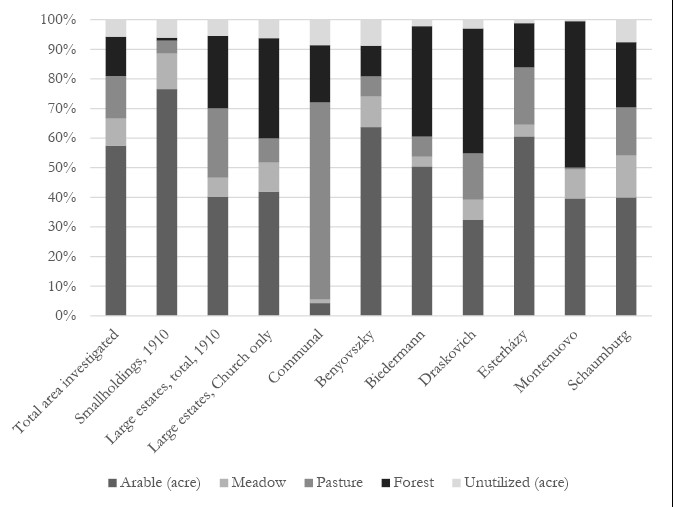

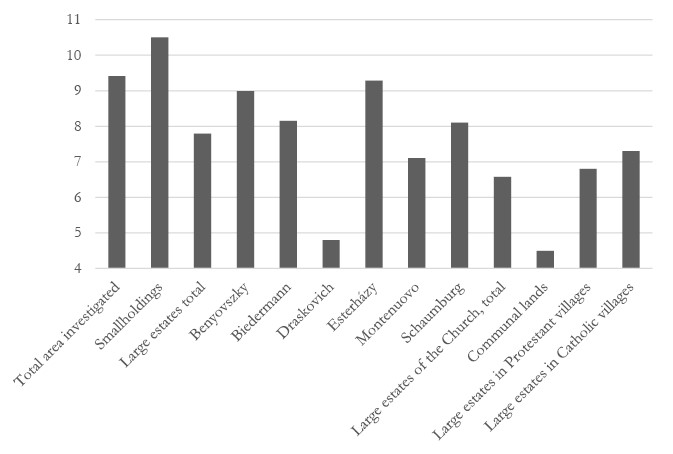

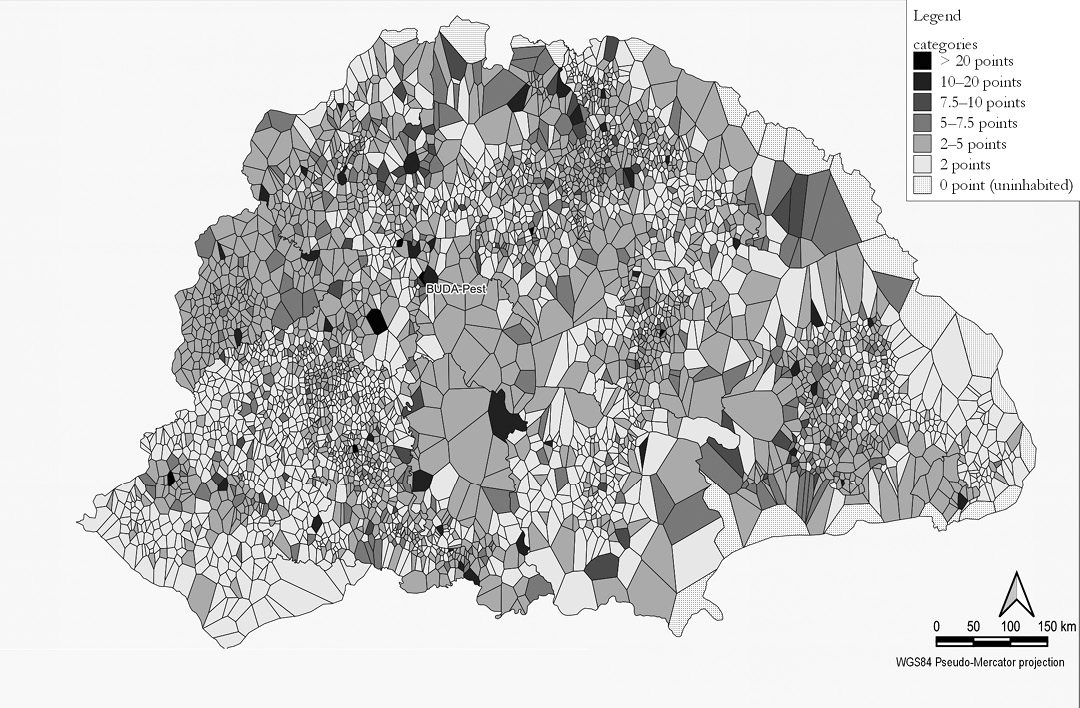

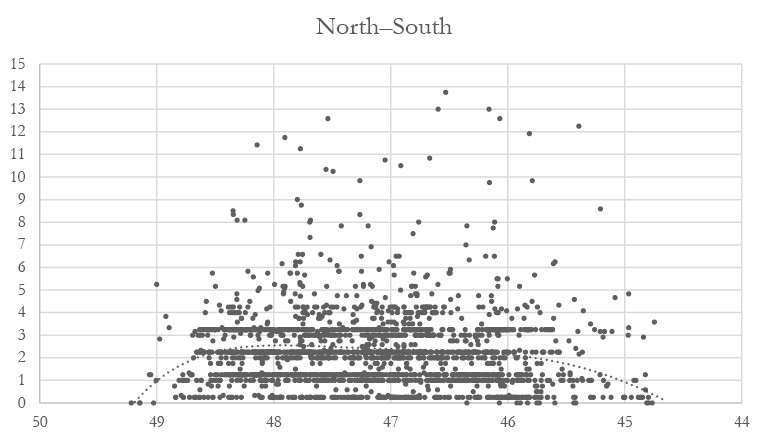

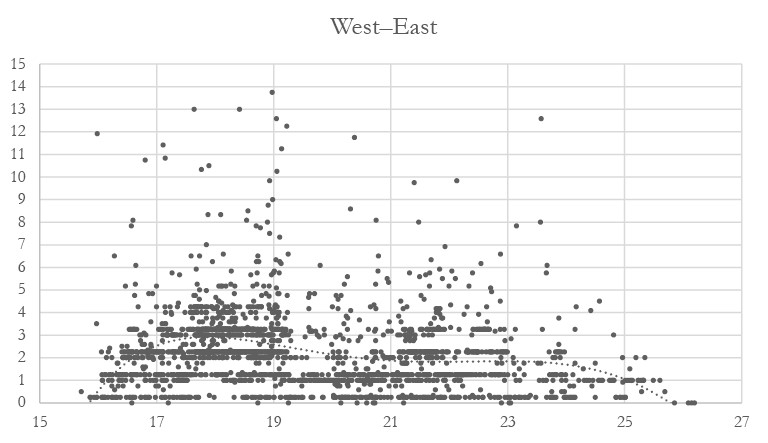

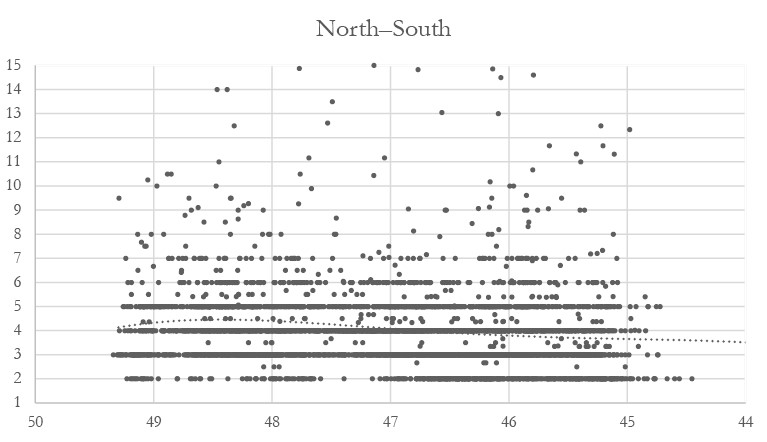

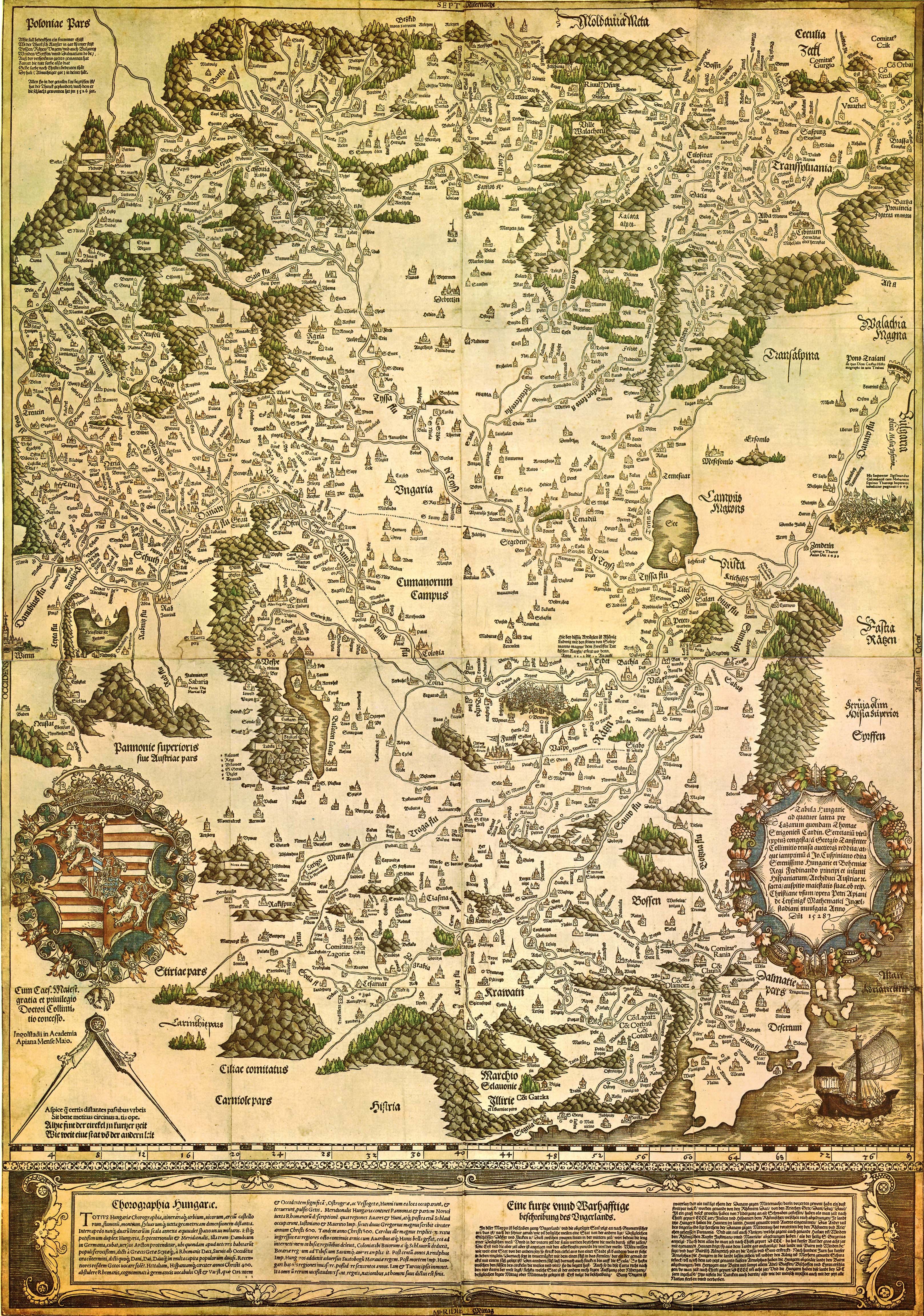

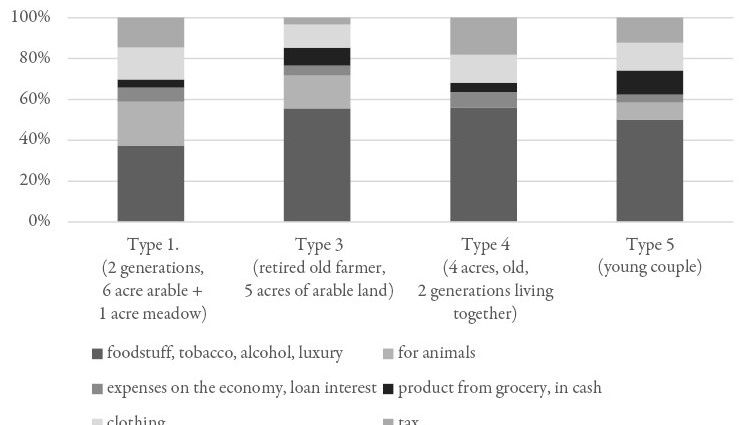

Figure 1. Incomes of different family types in Pusztaszakállas in 1932, as a percentage

In the case of Type I–V families, according to the data, a significant portion of the goods produced was consumed, essentially serving as an example of the independent peasant economy described by Chayanov. If the family’s financial situation required it, they also took on day labor for wages or for a share of the harvest. In the case of the vegetable gardener presented as a Type VI family, there was no mention of the garden vegetables that might have been grown by the family within the area of the settlement, nor was there any mention of what animals they might have kept. For a farm or farmstead producing for the markets, the value of bacon or fat consumed is likely irrelevant. Accordingly, only the costs necessary for the production of vegetables sold at the market have been included on the expenditure side too. The revenue mentioned also included the income made from the sale of vegetables. It is also true that they did not calculate the depreciation of machines and equipment when they calculated profits.

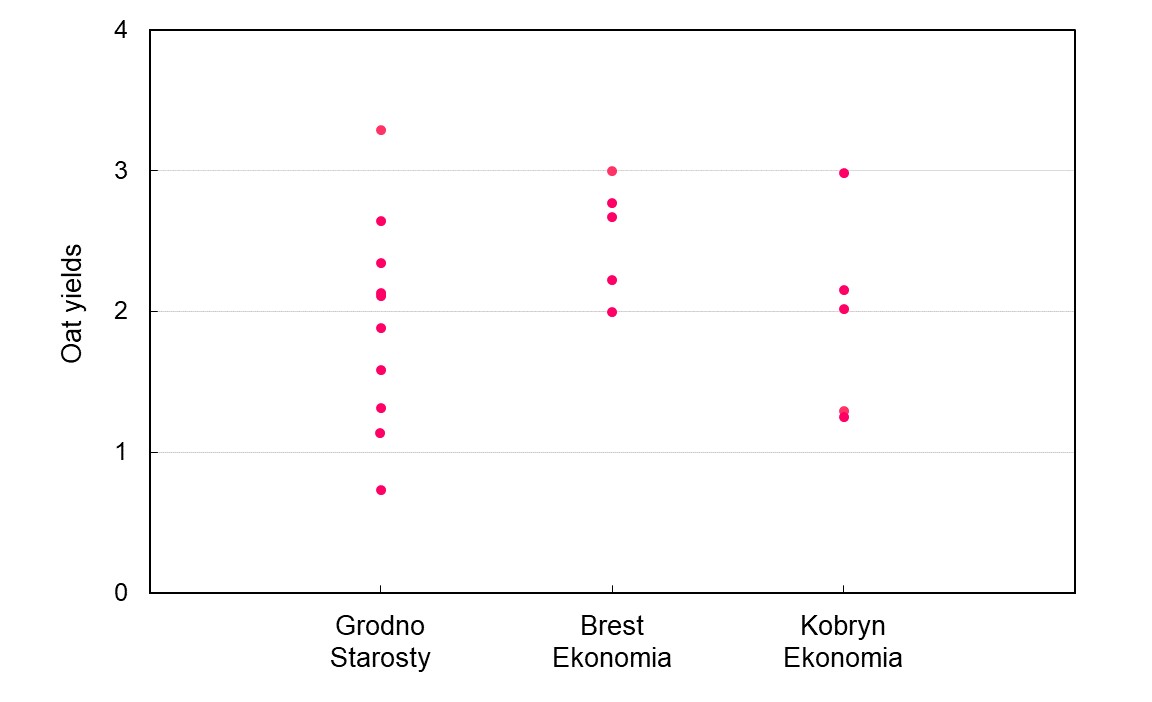

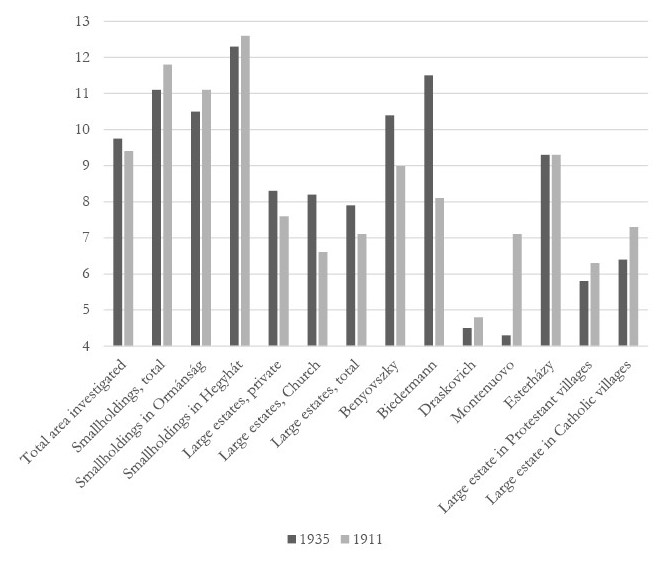

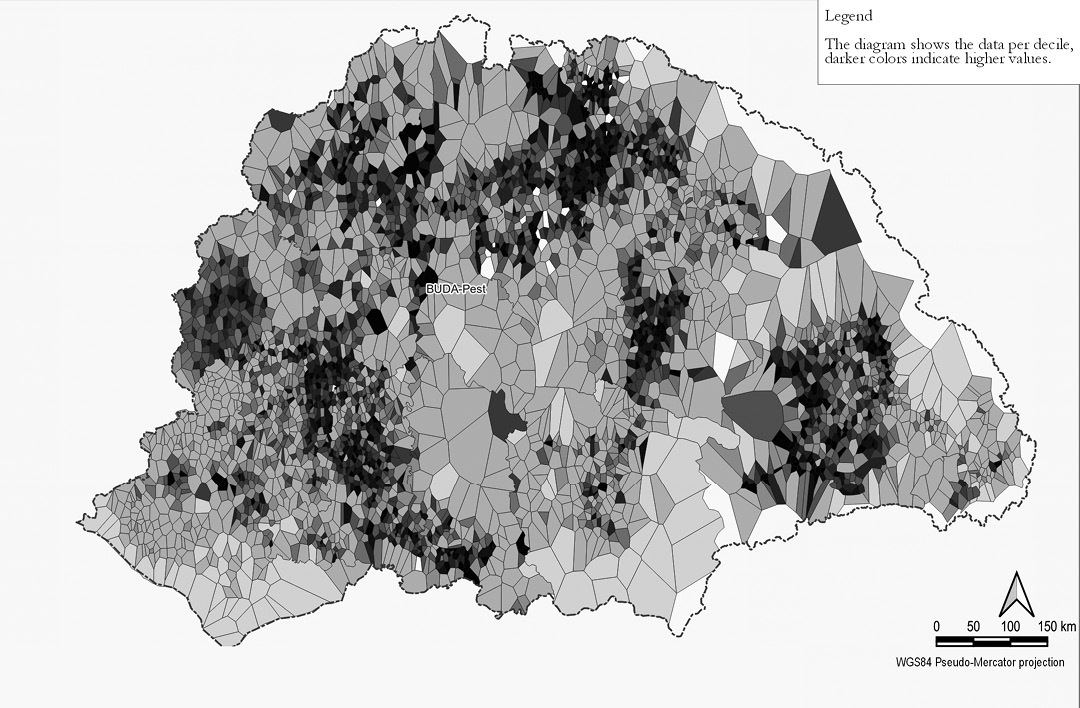

Figure 2. Expenses of different family types in Pusztaszakállas in 1932, as a percentage (in kind and in cash expenditures merged)

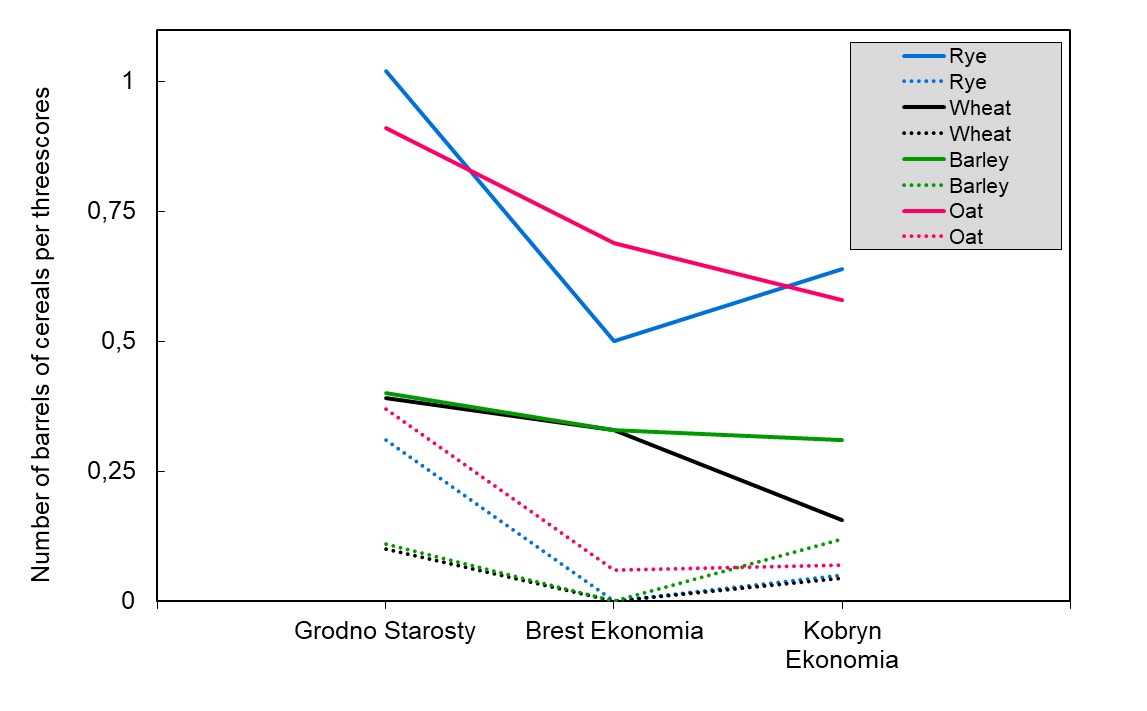

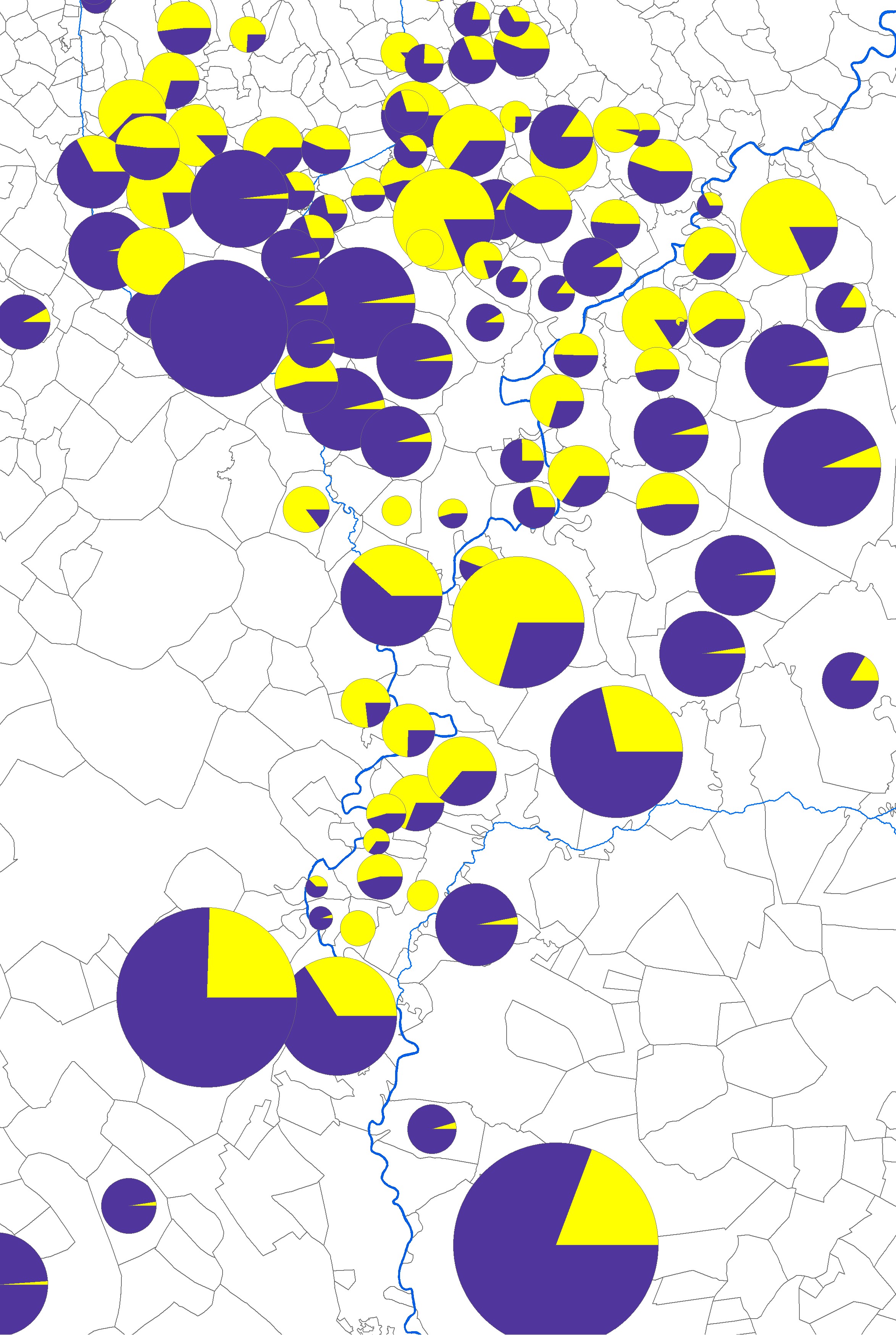

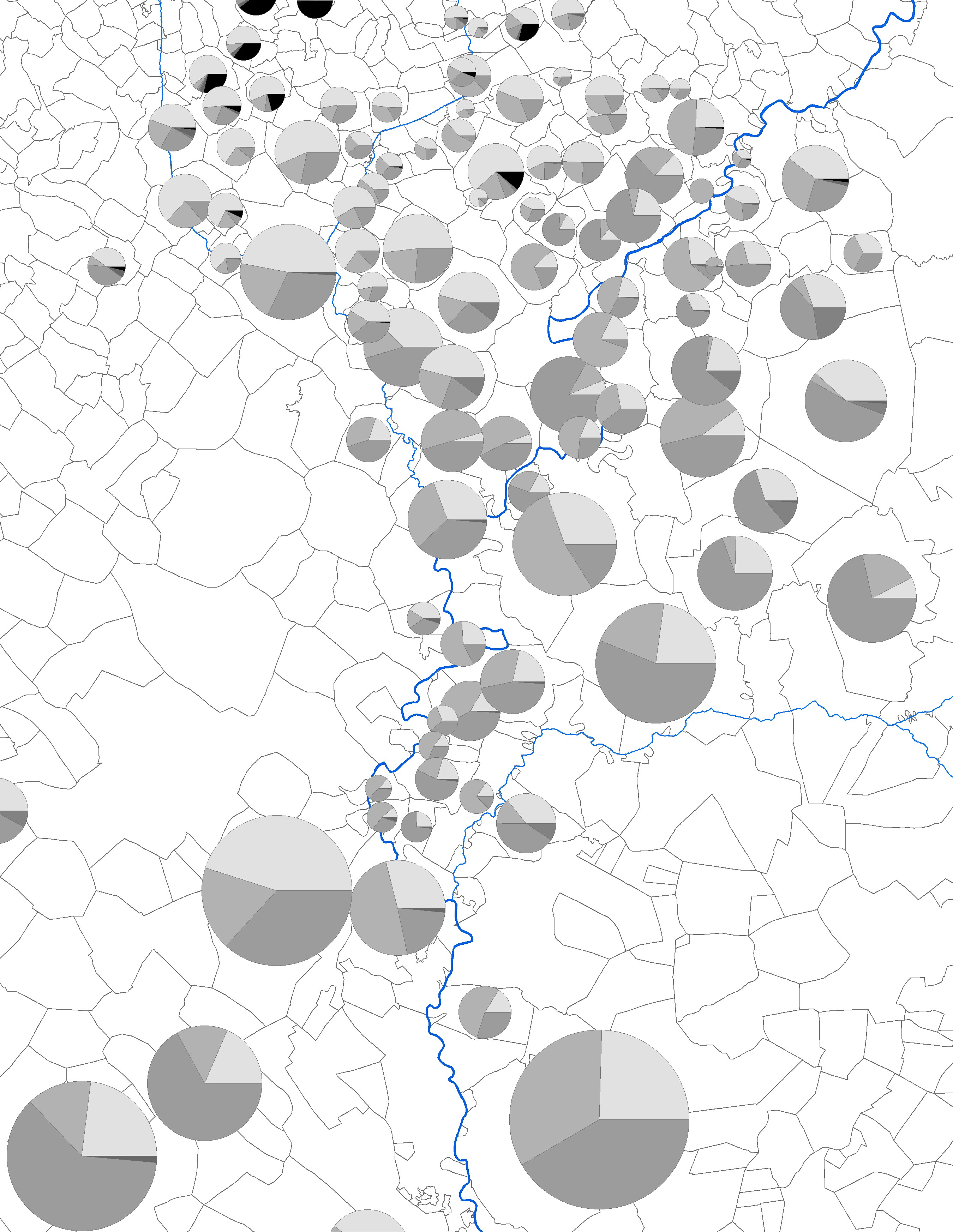

The families presented differed not only according to Laslett’s typology but also according to the sources of income, despite the similarity in field size. Two families earned wages as the main source of income, but there were also differences between them, whether in-kind or cash revenues dominated. In two other types of families (one multi-generational, the other with an elderly head of household), the work outside the farm played a subordinate role. Here, income from livestock or revenues from public goods (fishing) accounted for 30 percent of total income, indicating a major deficit in Hungarian statistics (the general lack of livestock censuses at the settlement level before 1930). The share of income from arable land (whether cash or in-kind) varied between 20 and 60 percent.

The expenditure side (both monetary expenditure and consumption in kind) showed less diversity. Despite the obvious tax evasion (and the significant tax arrears), taxes fluctuated between twelve and 20 percent of expenditures (and income), clothing accounted for a stable ten to 15 percent, while expenditure in grocery shops remained below ten percent, as did economic investments (building maintenance, livestock or land purchase). Self-catering accounted for half of expenditures. This, together with livestock, reached 60 percent for all four families (with complete data sets). Cash income (i.e. the value of products sold) did not exceed 33 percent of the income, and cash expenditure (items bought in addition to consumption produced by the peasant economy) accounted for 38 percent of expenditures. In general, the cash needs of self-sustaining farms not producing for the markets were higher than the annual cash income actually available, often due to rolling tax arrears or loan repayments.

The description of demographic aspects and characteristics in Molnár’s unpublished thesis, which proved significant factors in defining different types of families, has somewhat taken a back seat (unlike in the writings by other villager researchers). The descriptions of the financial circumstances of the families, although not discussed with the depth of public economics (finance-accounting), sought to avoid omitting even a single item (income, expenses, consumption goods produced within the framework of self-sufficiency, and even gifts), assigning a monetary value to each of them. If we look at his work through the lens of economics, then in comparison, the economist-statistician Mátyás Matolcsy considered the same factors as Molnár when determining Hungary’s national income in the 1930s, with one exception: Matolcsy tried to express the value of household work as well, ultimately calculating a total of 350 million workdays nationwide per year.107

The families introduced lived in modest, simple circumstances. Even the expenses of the sixth family presented did not reflect the high annual profit of 2,000 pengő. It is likely that the families presented by Molnár were in a better situation than the 96 families of the lowland working-class community examined by Kerék. The families presented by Kerék had an average of one or two cadastral acres of smallholdings, but Kerék considered the declining presence of pig farming as a sign of material “deterioration,” as only about one-fifth of the households were involved in raising pigs.108 In Pusztaszakállas, however, every family was engaged in pig farming.

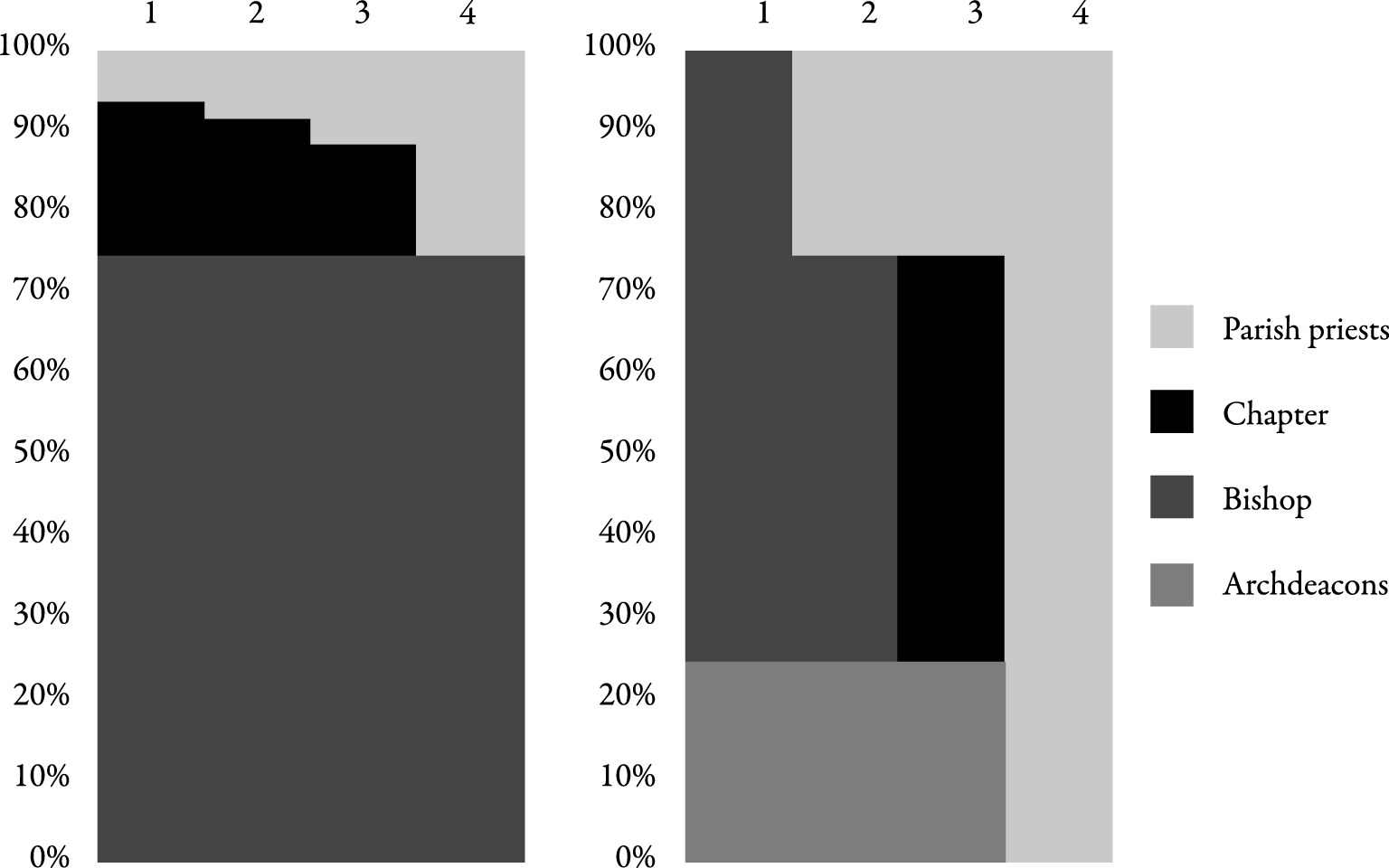

Molnár dealt with taxes in the case of each family, whether as their highest expense to cover in cash or an amount they owed in arrears. Among the taxes, the church tax was a matter of customary law (there was no written law regarding it), but the local population accepted it. In Törökszentmiklós, the church and the local leadership agreed that the local apparatus would collect this tax for a five percent commission, but this amount was left in the hands of the church as a donation.109

In the interwar period, taxes had to be paid based on numerous bases. There were about nine types of state direct taxes (such as the land tax and the house tax), which, on country average, could have accounted for approximately 60 percent of the total tax burden, while local taxes and surtaxes made up the remaining 40 percent.110 According to calculations done at the end of the 1930s, out of the annual direct tax burden of 513 million pengő, approximately 192.5 million pengő (37.5 percent) was allocated to agriculture, which amounted to roughly twelve pengő per cadastral acre.111 However, local conditions could have significantly altered this value. The payable taxes increased further if a municipality raised the burden with an additional surtax in order to increase its revenues for the sake of budgetary balance. We previously mentioned that Törökszentmiklós had a debt of more than a year’s revenue in the 1930s (debt was over one million pengő), so it is no coincidence that supplementary taxes began to rise as well.

Table 9. The theoretical tax burden of smallholders with five cadastral acres in the 1930s (pengő)

|

Type of tax |

Above five cadastral acres |

|

|

Average landowner net income (gold crown/landowner acre) |

13.5 |

|

|

Total net income of all categories (gold crown) |

67.5 |

|

|

Total net income (pengő) |

78.3 |

|

|

1 |

Land tax (20 percent) |

15.66 |

|

2 |

Householder tax (14 percent) |

10.00 |

|

3 |

Income tax (1–1,2 percent) |

0.00 |

|

4 |

Wealth tax (1‰) |

0.00 |

|

5 |

Extra allowance |

0.00 |

|

6 |

Disability support tax |

0.51 |

|

7 |

Public sick leave and childcare allowance supplementary tax |

4.11 |

|

8 |

Road tax (10 percent) |

2.57 |

|

9 |

Public work redemption |

3.70 |

|

10 |

Agricultural Chamber fee |

1.03 |

|

11 |

Water regulation fee |

2.00 |

|

12 |

County supplementary tax (32 percent) |

8.21 |

|

13 |

Municipal supplementary tax (75 percent) |

19.25 |

|

14 |

Dog tax |

2.00 |

|

15 |

Mix tax |

6.06 |

|

16 |

Church tax (10 percent) |

2.57 |

|

Total |

77.67 |

|

|

Land tax reimbursement |

-15.66 |

|

|

Net tax burden |

62.01 |

|

|

A gross tax per cadastal acre (pengő) |

15.53 |

|

|

Net tax burden as a percentage of the net income of the cadastral acres ( percent) |

79.20 |

|

|

Source: My compilation of data provided by Béla Bojkó.112 |

||

Béla Bojkó calculated his data on the share of tax from total incomes for several estate sizes, but he noted that he considered minimum values. If we compare the theoretical values of smallholders who owned five hectares of land (Table 9) with the tax burdens of families classified in Type I by Molnár (Table 3), it can be stated that the actual tax burden was higher in Törökszentmiklós.113 The land tax and house tax together amounted to 85 pengő, rounded off, while Bojkó’s calculations only came to roughly 25 pengő. The church tax was also much higher than the theoretical value in the case of the family in Pusztaszakállas (2.5 pengő versus 24 pengő), which may have been due to the higher number of children. In the case of the family in Pusztaszakállas, the amount to be paid for the exemption from public work was also higher. (3.7 pengő versus 24 pengő). The income tax indicated by Molnár for the Type I family in Pusztaszakállas was 19 pengő, while Bojkó did not take such an item into account at all.

If the result of a “sampling” is that five out of six families had trouble paying their taxes and the sixth, although it was in a much more favorable situation than the others, intentionally reported an incorrect tax base for the sake of more favorable taxation, then this can hardly been seen as a coincidence. According to Lajos Juhos, the problem with agriculture in the interwar period was that a farmer received loans at an interest rate of around ten percent, while the maximum profit that could be made in agriculture was about five percent. The outcome was indebtedness.114 The simplest method of compensating for this was tax evasion. If the farmer did not take out a loan, then an opportunity for modernization was missed, and the farm was self-sufficient at best. In the existing financial condition, it was not obvious for the average farmer that it was worth investing or even possible to invest in modernization.

Archival Sources

Magyar Nemzeti Levéltár Jász-Nagykun-Szolnok Vármegyei Levéltár [Hungarian National Archives Jász-Nagykun-Szolnok County Archives] (MNL JNSZVML)

IV.407. Jász-Nagykun-Szolnok Vármegye alispánjának iratai

Kéziratok gyűjteménye Sz./25.

Szakál, Károlyné. “Törökszentmiklós története 1932-től 1938-ig.” MA thesis, n.d.

Debreceni Egyetem [University of Debrecen], Faculty of Humanities, Dean’s Office

Hallgatói anyakönyvek [Student registers of the Faculty of Humanities, Languages, and History of István Tisza University from 1914 to 1949]

Molnár, Károly. “Pusztaszakállas gazdaság-formái” [The economic forms of Pusztaszakállas]. Geography Thesis, University of Debrecen, 1933.

Bibliography

Printed sources

A Törökszentmiklósi Községi Polgári Fiúiskola Értesítője az 1936/37. tanévről [The notification of the Törökszentmiklós Municipal Civil Boys’ School for the 1936/37 academic year]. Törökszentmiklós: Törökszentmiklósi Községi Polgári Fiúiskola, 1937.

A Törökszentmiklósi Községi Polgári Fiúiskola Értesítője az 1938/39. tanévről [The notification of the Törökszentmiklós Municipal Civil Boys’ School for the 1938/39 academic year]. Törökszentmiklós: Törökszentmiklósi Községi Polgári Fiúiskola, 1939.

Az 1930. évi népszámlálás. Part 2, Foglalkozási adatok községek és külterületi lakotthelyek szerint, továbbá az ipari és kereskedelmi nagyvállalatok [Census of 1930. Part 2, Occupational data by municipalities and rural inhabited areas, as well as industrial and commercial large enterprises.] Magyar Statisztikai Közlemények. Új sorozat, 86. Budapest: KSH, 1934.

Mezőgazdaságunk válsága számokban: A magyar mezőgazdaság jövedelmezőségének kimutatása számtartási eredmények alapján az 1927. évben [The crisis of our agriculture in numbers: The demonstration of the profitability of Hungarian agriculture based on accounting results in the year 1927]. Budapest: Országos Magyar Gazdasági Egyesület Üzem Statisztikai Bizottsága, 1930.

Mezőgazdaságunk üzemi eredményei 1933. évben: Az országos számtartás-statisztikai adatgyűjtés alapján [The operational results of our agriculture in the year 1933: Based on the national census statistical data collection] Budapest: Országos Magyar Gazdasági Egyesület Üzemstatisztikai Bizottsága, 1935.

Newspapers

Köztelek, 1927.

Secondary literature

Bagdi, Róbert. “Statisztikai módszerekkel mért fejlettség és szociográfiai valóság az 1930-as évek vidéki Magyarországán” [The development measured by statistical methods and the sociographic reality in rural Hungary in the 1930s]. In Magyar Gazdaságtörténeti Évkönyv, edited by Gábor Demeter, György Kövér, Ágnes Pogány, and Boglárka Weisz 199–227. Budapest: Bölcsészettudományi Kutatóközpont, 2022.

Bernát, Gyula. “A mezőgazdasági termelés jövedelmezőségéhez” [On the profitability of agricultural production]. Budapesti Szemle 208, no. 602 (1928): 372–84.

Bojkó, Béla. Magyar adórendszer és adópolitika (1919–1945) [Hungarian tax system and tax policy, 1919–1945]. Budapest: Püski Kiadó, 1997.

Botka, János, ed. “Törökszentmiklós.” In Adatok Szolnok megye történetéből [Data from the history of Szolnok County], vol. 2, 743–79. Szolnok: Szolnok Megyei Levéltár, 1989.