The Export Potential of Hungarian Agriculture and the Issue of Added Value between the two World Wars

the two World Wars

András Schlett

Pázmány Péter Catholic University

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Hungarian Historical Review Volume 13 Issue 3 (2024): 446-470 DOI 10.38145/2024.3.446

This study presents developments concerning Hungarian agricultural exports during a period when the production structure changed significantly and the international agricultural market changed fundamentally. As a result of the Treaty of Trianon, the market and logistic networks developed over the previous centuries had changed significantly, and new actors came to play increasingly prominent roles in trade relations in the Danubian Basin. Hungary, with its small consumer market but significant agricultural potential, had been fundamentally dependent on the value of its agriculture produce on foreign markets. However, the reorganization of the international market quickly brought to the surface the contradictions and structural imbalances of Hungary’s massive agricultural production. Analyses of the agricultural history of the past century repeatedly revealed the problematic nature of the low value-added production of Hungarian agriculture.

Keywords: Hungary, agriculture, trade, export potential, added value

Introduction

The evolution of a country’s export activity is mainly determined by two broad sets of factors. The first is the country’s internal economic conditions, and the second is the country’s interactions with the world around it. By analyzing developments involving Hungarian agricultural exports between 1929 and 1937, Miklós Siegescu shows in detail how domestic economic factors, such as production surpluses and price levels, and international economic conditions influenced Hungarian agricultural exports. His study also discusses the development of Hungarian foreign trade relations, especially with Austria, Germany, Italy, and Czechoslovakia and the effects of trade policy measures. It also provides detailed statistical data on the evolution of Hungarian foreign trade and agricultural exports, with emphasis on the role of the world market and international trade policy in the economic outcomes.1The interwar period bore witness to major changes in both areas.

Based on these considerations, the present study examines the challenges faced by Hungary in its trade policy and the results of its attempts to respond to these challenges. The situation in Hungary was aggravated by the fact that nearby East European countries also produced massive agricultural exports, and West European industrial states granted significant advantages to overseas agricultural products compared to Hungarian goods. These factors made Hungary’s export markets unstable and difficult to predict.

Against a backdrop of restructuring and a fundamental lack of confidence in Hungary among its trade partners (in part since Hungary had been an enemy country for many of them during the war), the country had to seize every opportunity to find external markets for its agricultural products. Thus, the interwar period bore witness to an intensive search for foreign markets from the postwar crisis through an economic boom (peaking in 1929) and the Great Depression (1930–1934) to a new phase of prosperity (from 1935) marked by an economic policy of continuously increasingly military investments.

Hungary needed to increase its exports and achieve a positive trade balance to secure enough gold standard currencies to finance its massive prewar and postwar foreign debts. However, the demand for Hungarian export goods (mainly low added-value products which were easily found elsewhere) was volatile, and the prices of agricultural produce were generally going down. This resulted in a usually passive balance of trade and increasing financial (and political) indebtedness.

In the discussion below, I examine the evolution of the structure of Hungarian agricultural exports, with particular emphasis on the proportions of lower and higher value-added products and attempts at diversification.

Agriculture after the Treaty of Trianon

Agricultural lands in Trianon Hungary were put to various uses in proportions that differed significantly from the ways in which they had been used when the country had been part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. While the share (but not net amount) of arable land significantly expanded (from 43.9 percent to 60.3 percent), the forested area drastically decreased, from 27 percent to 12 percent. Only a fraction of the gardens (25.2 percent), meadows (25.2 percent), and pastures (30.6 percent) and a larger share of vineyards (68.9 percent) that had been within the borders of the country when it had been part of the Dual Monarchy remained within the new borders.2

In the new national territory, the distribution of land ownership showed a different structure compared to the pre-Trianon situation. Due to the land reforms, the imbalance in land distribution slightly decreased. The proportion of small and large estates changed, reflecting the distinct characteristics of the areas which had been made part of the neighboring states and the territory which remained to Hungary, rather than a worsening of the overall imbalance.

The proportion of small farms decreased, and many peasants found it increasingly difficult to live off their land. While 70.1 percent of farms over 1,000 cadastral yokes (1 yoke equals 0.58 hectares) remained within the new boundaries, the country lost 70 percent of small farms under 10 yokes. Additionally, Hungary retained 40.1 percent of farms between 10 and 50 yokes, 46.1 percent of those between 50 and 100 yokes, 46.7 percent of farms between 100 and 200 yokes, and 57.8 percent of farms between 200 and 500 yokes.3

The proportion of large landholdings did not change drastically. In terms of land ownership, before Trianon, 30 percent of the arable land was owned by large landholders with more than 1,000 cadastral yokes. In the new borders, this figure increased to 44 percent. However, it is important to distinguish between landholdings and landholders when analyzing these figures.

As a result of the territorial changes, the structure of the agricultural labor force differed in post-Trianon Hungary. The ratio of agricultural wage laborers to smallholders increased.If we consider smallholders with less than five cadastral holds of land as part of the agrarian proletariat, the proportion of the population involved was significant. However, these proportions depend on how ownership is defined. Different approaches to measuring land ownership, either through occupational classification or cadastral records, lead to varying results. For example, some agricultural laborers owned small plots of land, while others, who leased land, did not appear as owners in the statistics. The labor market situation was somewhat alleviated by the loss of regions such as Upper Hungary, which traditionally employed large numbers of seasonal workers, thus reducing the pressure on Hungary’s agricultural workforce.4

Table 1. Different types of agricultural producers (as a percentage)

|

Before Trianon |

After Trianon |

|

|

Owner and tenant |

35.2 |

31.4 |

|

Other independent |

0.5 |

0.7 |

|

Family worker (unpaid) |

31.1 |

21.9 |

|

Administrative manager (gazdasági tisztviselő) |

0.2 |

0.3 |

|

Farm hand (cseléd) |

9.9 |

14.7 |

|

Agricultural laborer |

23.1 |

31 |

|

Source: “A háború előtti Magyarország,” 292–93. |

||

Exposure to External Markets

As a consequence of the Treaty of Trianon, Hungary became heavily dependent on foreign trade. The country lost the secure markets it had had access to under the Monarchy. The former single market was replaced by countries with independent economic policies, new customs borders, tariffs, and independent currency zones. Distrust among the successor states contributed to the strengthening of exclusionary policies, as many of the newly emerging states interpreted the post-Trianon situation as requiring a restructuring of old economic relations and a partial or complete reorganization of traditional market and capital relations.5 However, the economic interdependence of the countries in the region is well illustrated by the fact some 20 years later, the Little Entente had not been able to eliminate export-import trade with Hungary. In fact, a significant share of the trade in goods among the states of the Little Entente was routed through Hungary by rail and water. Almost only arms shipments avoided Hungary.

Before 1918, most of Hungary’s agricultural exports did not go beyond the borders of the Monarchy, i.e. agricultural produce was exported to a protected market of 52 million people, where prices were significantly higher than on the global market. Hungary had been in a customs and monetary union with the Austrian hereditary provinces for centuries and with Bosnia and Herzegovina for decades. Austria was able to absorb Hungarian agricultural produce, thus protecting the prices. With the breakup of the Monarchy, Hungary lost this advantage. The limited domestic market made agricultural exports especially vital, but the opportunities to sell products and produce became increasingly limited.6 The country could only sell its surpluses at world market prices and was vulnerable to external market and political changes.7 Moreover, this happened at a time when Hungarian agriculture, which had high costs, could only achieve low export prices. Whereas before 1918 Hungarian agriculture had benefited from the protection of high tariffs, it now faced open competition on the world market.8

In 1920, many of the territories that were ceded were heavily dependent on agricultural imports, as their own agricultural production had not been sufficient to meet the needs of their population even before 1919. Since the remaining territory had already produced the largest share of agricultural surpluses, the relative surplus of agricultural production increased significantly after the signing of the Treaty of Trianon. There was no demand within the country for a significant portion of the agricultural produce, so this surplus had to be sold on foreign markets. Between 1924 and 1938, 55–70 percent of the agricultural produce brought to market was sold abroad, as was 55 percent of cereals, 38–40 percent of sugar and sugar beet production, 25–30 percent of tobacco, and 20 percent of the potato crops. And this list includes only the items that were exported in large quantities during the period in question. One could add to it to include items that were only occasionally exported in large quantities.9

The division of labor that had developed over the course of centuries in the Carpathian Basin and the forms of cooperation among specialized areas of production and consumption that had been consolidated under the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy were greatly hindered by the new postwar frontiers, and this was only aggravated by the political rivalry and nation-building programs initiated by the successor states, including the creation of unified, protected national markets. No state in the region was an exception. Hungary, Romania, and the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes all focused on industrial development, while Austria and Czechoslovakia strove for agricultural self-sufficiency. These tendencies put the theory and practice of comparative advantage into a kind of parenthesis, and, in a spirit of mutual mistrust, the states of the region strove to build complex national economies, i.e. economies that provided strategic security. All this created an economic structure in the Danube basin in which several parallel capacities operated at an unnecessarily high cost but which, in the event of war, was less economically vulnerable to the need to import items of strategic importance. Economic cooperation among the nations of the former Monarchy was thus hampered not only by higher tariffs but increasingly by politically motivated economic policies, leading in the longer term to a decline in foreign trade relations. In the years following the war, however, autarchic ambitions were less prevalent for a time, and traditional specialization and cooperation continued for a while.10

This economic cooperation was encouraged by Article 205 of the Treaty of Trianon (identical to article 222 of the Austrian peace treaty), which called for a regional customs agreement among Austria, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia within five years of the signing of the treaty. However, these states were unable to conclude such a treaty and instead maintained the obsolete tariff system inherited from the Monarchy, supplemented by special provisions and import restrictions. Hungary, however, paid considerable attention to promoting foreign trade relations through bilateral and multilateral trade treaties and the application of the so-called most-favored-nation principle. Hungary needed these advantages because its relatively costly agricultural sector and less developed industry were the only way to compete on export markets.

In the early 1920s, in the absence of a general customs agreement, the region’s foreign trade relations were facilitated by bilateral treaties. An important consideration in the setting of tariffs was to blunt the differences between the producer groups involved in agricultural exports and the industrialists wishing to protect domestic industry. Agricultural import tariffs were therefore set at low levels, since they posed little threat to domestic sales, while the high import tariffs on industrial products were used both to protect the nascent industrial sector in Hungary and to provide indirect support for the marketing of agricultural produce, in so far as promises to reduce industrial import duties could be used to obtain more favorable terms in trade agreements.

These tariffs and agreements alone could hardly have affected the structure of Hungarian exports and imports. In Trianon Hungary, agricultural surplus production was a fundamental characteristic due to the higher proportion of land suitable for cereal production. After 1920, the country was dependent on the income brought in through agricultural exports, mainly of grain and flour. Whereas immediately before the war, in years of particularly poor harvests, Hungary had had hardly any surpluses crossing customs borders, after the war, economic prosperity depended mainly on these agricultural exports.

Austria and Czechoslovakia remained important partners, but the Hungarian agricultural sector faced unprecedented difficulties in the face of general international oversupply and competition in transport and tariffs, as well as world market prices. Its low productivity and relatively high production costs made sales difficult, even though Hungary had a vital need for export earnings. It had to meet its international payment obligations, make up for an increasingly pressing shortage of capital, and cover the large costs of imports of raw materials and consumer goods by Hungarian industry. Hungarian agriculture was unable to meet these demands as part of the new international constellation, and the trade balance showed a significant deficit until the end of the 1920s.11

Gyula Balkányi paints a vivid picture of the loss of markets and its effects in Közgazdasági Szemle (Economic Review):

Today’s generation grew up in a nursery, used to an economic milieu where the “market” was the internal consumption of a large economic area in a customs union with our country. “Our market,” as we remember it, is an area to which producers from competing countries do not have equal access. The market for Hungarian grain, flour, cattle, pigs, fat, bacon, fruit, and wine was, as we remember it, Austria. Not in the way that we were allowed to export goods there. But in the way that others were not allowed to export there. The market, in this exclusive sense, was lost to us. (…) While we were in Greater Hungary and in a customs union with Austria, we did not have to worry about competition from overseas countries. Our goods were known in Austria, our production was adapted to this market. And if there was a threat to our markets—competition by Italian or Spanish wines, frozen meat from Argentina—we could always help by raising customs duties or banning imports. (…) Now, however, we are on a market where our competitors also operate, where we must strictly align our prices with the pricing demands of our rivals, and where we must strive to offer the quality that consumers’ desire. If we provide a better product than our competitors, we must use the most extensive promotion to convince buyers of the superiority and excellence of our prices. The notion that even such a market can be ours must become deeply ingrained in the mindset of today’s generation.12

The Collapse of Agro-Vertical Integration

Following the Treaty of Trianon, there was a serious imbalance between agricultural raw material resources and processing capacity. It soon became apparent that the highly productive milling, sugar, beer, and leather industries which had previously been designed to supply the Monarchy were unable to utilize their existing capacities. While a significant proportion of the raw material base, including the most important grain-producing areas (South Bačka, Banat, Grosse Schütt), was detached from Hungary, the processing capacities of the Budapest mills were concentrated in the remaining territory of the country.13

The situation in the timber industry was similar after Hungary’s loss of most of its forestlands to the neighboring countries. The redundancies were soon followed by factory closures: mills became warehouses and breweries became chocolate and sugar factories and textile mills.

The milling industry was hit hardest, losing a significant proportion of its natural raw material base and a significant part of its upstream markets along the River Danube. Budapest mills also lost Serbian and Romanian wheat as the milling trade ceased.14 Previously, the milling industry in Budapest sourced 50–60 percent of its raw materials from the detached territories. The mills were able to grind 64.5 million quintals of grain, whereas the country’s grain production in the early 1920s averaged 24.2 million quintals. In 1913, 13 mills were working in Budapest, compared with only 9 in 1921. The rest were idle. The mills were also operating at a reduced capacity.15

The situation was made critical by the customs policy pursued by Austria and Czechoslovakia, the only countries of the one-time Monarchy which still imported substantial quantities of Hungarian flour in the 1920s. Both countries were keen to support their own milling industries and therefore preferred grain imports to flour imports. The autonomous Austrian agricultural tariffs of 1925 and the Czechoslovak agricultural tariffs of 1926 greatly reduced Hungarian flour exports and increased grain exports. As a result, Hungarian mills were able to use only 20-25 percent of their capacity, and thus the production costs were far higher than the costs incurred by their competitors. This led to a crisis in the milling industry.16

By the end of the decade, the circumstances had improved, and the domestic milling industry was functioning at about 40 percent of its prewar capacity. This improvement was due to the increased demand for Hungarian flour, which can be partly explained by the stabilization of the international economic situation and the restoration of trade relations. Still, the importance of the milling industry after Trianon is shown by the fact that it accounted for 13–15 percent of the total industrial output in the 1930s, topping all other branches/categories except for textiles and the iron and metal industries.

As a result of the Treaty of Trianon, twelve of the 30 sugar factories in operation at that time remained in Hungary, accounting for 41 percent of the beet processing capacity in 1914. The neighboring countries acquired 48.1 percent of the territories which had been used for sugar beet production.

The remaining factories represented 43 percent of the beet processing capacity in 1912. The industry had to cope with serious external and internal problems. As with the milling industry, it had lost part of its natural raw material base (especially to Czechoslovakia) and a significant part of its upstream markets. The decline in sugar exports is illustrated by the fact that, whereas in 1913 they amounted to 68.9 million gold crowns, in 1926 they were only 23.9 million. Underutilization of capacity and low production volumes due to low domestic consumption resulted in higher unit costs.17

By 1923, sugar production was already covering domestic consumption, and exports also began. By 1928–29, production reached 82 percent of the prewar (proportional to territory) production level. As a result of the 1929 crisis, production significantly declined, and at the lowest point of the crisis in 1932–33, it fell to 42 percent of the pre-crisis level. The 60 percent share of exports in 1929 had fallen to 4 percent by 1938 as a result of the fall in international sugar prices. Even with cheap exports at dumped prices of eight to ten pengős (1.4–1.75 dollars) per quintal, sugar factories were still making minimal profits, but they were threatened by financial collapse. They asked the Government to reduce the high taxes on sugar (sugar tax, treasury share, sales tax), amounting to 52 percent of the 1.27 pengő (0.22 dollar) retail price, but in vain.18

The New Customs System

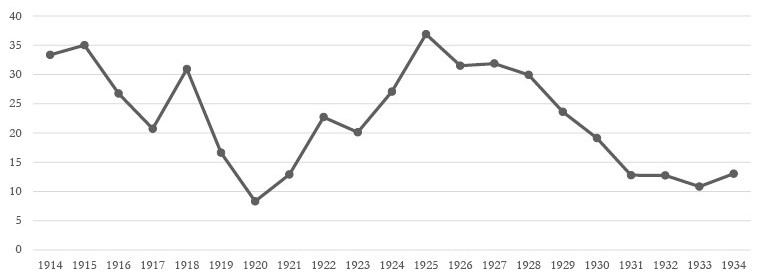

With the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, the previous customs system became obsolete, and establishing the country’s economic independence became a pressing task. The creation of a new customs tariff system was an essential means with which to strengthen the Hungarian economy. However, the rapid introduction of the new tariffs was made more difficult both by certain clauses of the peace treaty (which required most-favored-nation concessions for the Allied and Associated Powers) and by the conflicting interests of the domestic industrial and agricultural lobbies. According to the those working in agriculture, the reestablishment of free trade within the former Monarchy would be the ideal solution when building new regional trade relations, while those in industry favored the creation of a strong system of protective tariffs. The former did not reckon with the fact that Austria and the Czech Republic how already begun to pursue policies designed to protect and support the farms created by the postwar land distribution and that autarkic agricultural policies were being strengthened on the former export markets. This made it impossible for a reciprocal trade policy to develop, and the surplus production of cereals in the early 1920s also provided these industrialized countries with cheaper import opportunities. Contemporaries realized that the war had shattered the quasi-equilibrium on the agricultural market of the previous decades. The increase in demand for food and raw materials and the drastic drop in production in some areas (or the drop in exports due to the war) encouraged the United States and other countries less affected by the war (e.g. South American countries) to increase their output in agriculture and food products. During the postwar economic recovery, when production began to reach prewar levels anyway, these surpluses resulted in a significant oversupply and caused a drop in world prices (Fig. 1). Austria bought one-third of its cereals from the United States, and Czechoslovakia bought half of its flour from the United States.19 This was an awkward consequence of the foreign trade struggles and regional “self-isolation” policies among the small states of Central Europe.

Figure 1. The average annual price of wheat between 1914 and 1934 (Pengő per 100 kilograms). The low prices from 1915 to 1921 for all grains (wheat, rye, barley, oats, corn) were government-regulated maximum prices aimed at curbing speculation and inflation.

Source: Rege, “Magyarország búzatermelésének,” 463, 471, 474; Szőnyi, “Gabonaárak,” 204.

Customs policy debates were most heated over the 1923 tariff bill, which was strongly protective of industry and was intended to further rapid and far-reaching industrialization. Critics emphasized that Hungary, as an agricultural country, should be cautious when offering strong protections to industry as a means of developing the national economy. The new tariffs would foster industrial development only if they did not endanger the interests of the agricultural sector and consumers.20

Finally, the new customs regime introduced in January 1925 included more and higher import tariffs (30 percent on average). While tariffs on light industry products reached 50 percent, certain agricultural equipment and major raw materials were allowed to enter the domestic market duty-free. The new system also fueled the hope that a reduction in certain tariffs based on reciprocity could serve as a basis for negotiating easier placement of Hungarian agricultural exports.

Foreign Trade Agreements

In the interwar period, every small Central European country sought to protect its domestic market from foreign competition while also aiming to secure export opportunities for its domestic producers. However, this dual objective posed significant challenges during international trade negotiations, as protectionist tariff policies and efforts to promote exports often represented conflicting interests. As a result, the formation of customs and trade agreements between various countries was often prolonged and required compromises.

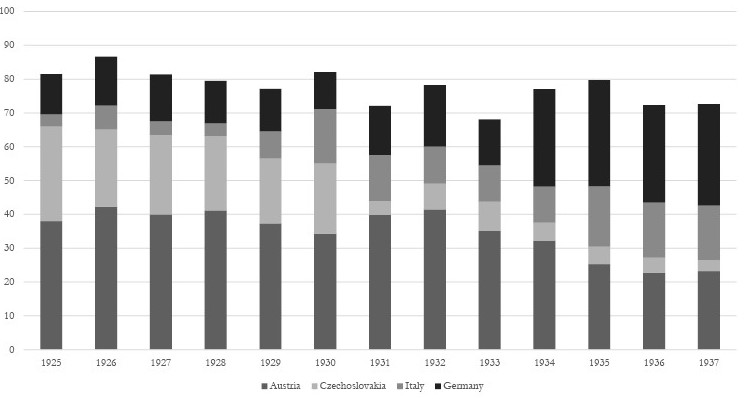

In the period between 1925 and 1929, the main objective of Hungarian trade policy was the negotiation and adoption of bilateral agreements. The principal aim was to secure favorable conditions, especially low tariffs, for Hungarian agricultural and food exports. The strategic importance of this is also shown by the fact that agriculture provided 60 to 65 percent of Hungary’s total exports throughout the period. In order to minimize the deficit in the foreign trade balance, every effort had to be made to ensure that agricultural products could reach the markets of potential importing countries.

The most important trade partner, of course, was Austria. Its share of Hungary’s exports declined significantly in the 1920s, from 60 percent before the war to 34 percent by the end of the decade, but it still remained Hungary’s most important trade partner. The central issue of the Austro-Hungarian negotiations was the level of Austrian tariffs on Hungarian agricultural goods and Hungarian tariffs on Austrian industrial goods. After lengthy negotiations lasting some 14 months, the treaty regulating trade between the two countries and the supplementary tariff agreement were concluded on May 9, 1926.

Significantly, the reduction of import duties on wine and flour was the most contentious issue in the Hungarian proposals and the one on which the Austrians were least willing to make concessions. In the end, the agreement was concluded, which was regarded in economic circles as the first significant step toward boosting foreign trade. However, the protectionist spirit that prevailed was illustrated by the fact that in December 1926, a Christian Socialist representative, speaking for the agricultural representatives, called for a review of the recent agreement and an increase in the tariff rate for agricultural products.

In the end, the agreement was concluded. In economic circles, it was regarded as the first significant step towards boosting foreign trade.

In the spring of 1927, a similar treaty was concluded between Hungary and Czechoslovakia after difficult diplomatic negotiations. This treaty was all the more important, because a previous agreement between the two countries, reached in 1923, had not contained a tariff section and had not specified the meaning of the “particularly favorable treatment” that the two parties had pledged to accord each other. Thus, the 1923 agreement did not substantially further the expansion of Hungarian agricultural exports to Czechoslovakia, and it also did not prevent Czechoslovak agricultural protectionist measures. From time to time, the Prague Government issued bans on the import of Hungarian flour and increased tariffs on certain agricultural products.

Thus, following the political disintegration of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, previous trade relations also began to deteriorate. Although Czechoslovak industrialists and Hungarian landowners would have been interested in establishing relations, both had lost political influence in their respective domestic contexts.

In Hungary, the lobbying power of industrial capitalists increased, while in Czechoslovakia, those involved in agriculture gained influence, and they were opposed to any compromise. Although negotiations for a trade treaty were underway, they progressed very slowly and the establishment of relations on a new basis was hampered by political differences. Finally, the introduction of new Hungarian tariffs made it imperative to normalize trade relations. A trade agreement was concluded on May 5, 1927, based on the principles of most-favored-nation treatment and parity.

The agreement reflected stronger agricultural protectionism in Hungary and industrial protectionism in Czechoslovakia. When the agreement was reached, trade between the two countries was already in decline, and the decrease was particularly marked in exports from Czechoslovakia to Hungary. Imports of raw materials from Czechoslovakia continued to increase, but textile imports fell, very much in line with the intentions of Hungarian industrial policy. While in 1924 textiles still accounted for half of Czechoslovak exports to Hungary, in 1929 they accounted for just over a third. The Czechoslovak government, however, welcomed the decline in Hungarian agricultural exports and intensified its trade relations, if only for political reasons, with the two other Little Entente states.21

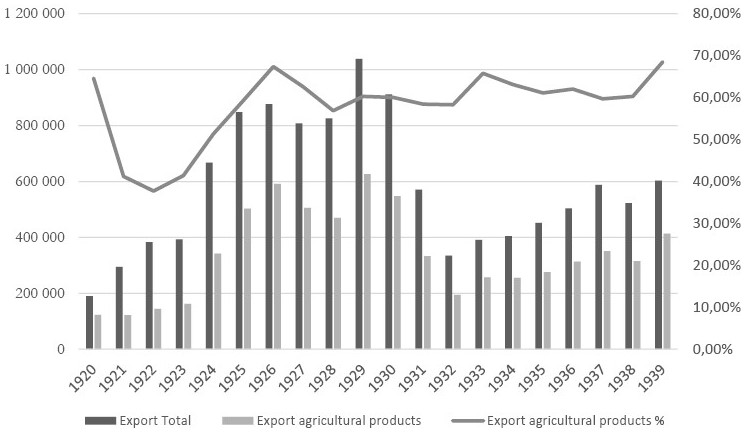

The Great Depression

The global economic crisis immediately disrupted the slowly developing trade relations and significantly worsened the sales position of Hungarian agriculture. In addition to the decline in export volume, the price drop of export goods also had a detrimental effect on Hungary’s foreign trade balance. The fall of agricultural prices alone between 1929 and 1931 caused a 100 million pengő (17.4 million dollars) drop in Hungary’s trade balance. The dramatic fall of the ratio of agricultural prices to industrial prices dealt a particularly strong blow to the trade balance, since Hungary exported mainly agricultural produce and imported mainly industrial goods. As a result, in 1932 imports fell by 39.1 percent and exports by 41.4 percent.22

Figure 2. Changes in exports between 1920 and 1939 (thousand pengő)

Source: Based on the data from the MSK, New Series, vols. 75, 77, 78, 80, 81, 82, 84, 85, 95, 98, 101, 106, 109, 111.

As countries sought to balance their trade, they responded to the crisis by strengthening their protectionism. The culmination of this process was Czechoslovakia’s withdrawal from the trade agreement with Hungary in 1930. Czechoslovakia intended to strengthen its economic ties with the other two Little Entente states by significantly reducing trade with Hungary. In the non-treaty situation, as of 1930, Hungary’s exports to Czechoslovakia fell from 16.8 percent of total exports to 4.2 percent the following year. Between 1929 and 1931, Hungary’s total exports fell by 45.1, while exports to Czechoslovakia fell by 86 percent. As a result of the crisis, Hungarian agricultural exports fell sharply both in volume and especially in price. The maximum agricultural export of 626 million pengős in 1929 fell to a minimum of 195 million pengős in 1932.23

Hungarian agricultural policy reacted with the introduction of the boletta system (July 1930) and the price premium system (July 1931) as an immediacy measure for the sale of agricultural produce, as well as intervention buying. Long-term solutions also had to be introduced without sacrificing the farmers’ free choice of production. Károly Ihrig, a prominent agricultural economist of the era, saw the key to expanding sales opportunities in improving the marketability of products and establishing cooperatives that would ensure greater organization and profitability for small farms.24 Kálmán Ruffy-Varga was of a similar opinion, stressing the need for official certificates issued by the state for each type of Hungarian wheat in response to the quality requirements of foreign countries, which allowed only the highest quality wheat to be exported.25

Foreign Trade Agreements in the 1930s

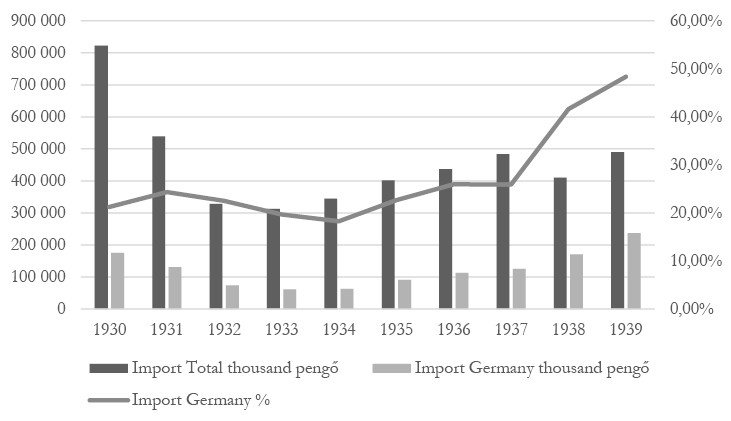

For Hungary, finding the way out of the struggles it faced with agricultural exports was facilitated by the opening of the German, Italian, and Austrian markets. In the 1930s, the agreements made with these countries became the foundation of Hungary’s foreign trade. Under an agreement concluded in Rome in May 1934, Italy and Austria undertook to purchase Hungary’s surplus wheat at a profitable price. By this time, Germany had also realized that it was a mistake to use agricultural tariffs to hinder agricultural imports from countries in which Germany also sought to sell its industrial products.

From the onset of the economic crisis, German foreign trade policy increasingly reflected the effort to make concessions to the agricultural exports of the countries in Central and Southeastern Europe to secure markets for German industrial goods. Through bilateral trade agreements, Germany committed to purchasing agricultural products from Hungary.26

This was influenced by the realization that the Südostraum, “abandoned” by the Western powers, could easily be tied to Germany by bilateral trade agreements which would serve long-term German geopolitical aims. However, there was also a simple economic and financial reason to open towards the markets to the east. Germany had lost its previous overseas sources of raw materials due to currency difficulties. Furthermore, the German agricultural market could provide a solution to the most serious problems faced by the countries of this region, especially Hungary, after the breakup of the Monarchy: the permanent crisis of overproduction caused by the loss of agricultural export markets. In 1934, a bilateral agreement was reached between the two countries, a supplement to the 1931 trade treaty, allowing Hungary to sell substantial quantities of grain, livestock, fat, meat, and bacon in Germany. Within one year (in 1934), Germany’s share in Hungary’s exports doubled (from 11.2 to 22.2 percent) and then continued to increase until 1938, when, because of the Anschluss, Hungarian exports to Germany nearly doubled again (from 24.0 to 45.7 percent). Meanwhile, Hungarian imports from Germany rose from 14.9 percent (in 1933) to 24.9 percent (in 1937) and then to 43.9 percent in the year of the Anschluss. By the mid-1930’s Germany had become Hungary’s most important foreign trade partner, and by the end of the decade, half of Hungary’s foreign trade was directed to and received from Germany.

Figure 3. Changes in export between 1930 and 1939

Source: Based on the data from the MSK, New Series, vols. 81, 82, 84, 85, 95, 98, 101, 106, 109, and 111.

One of the consequences of the boom in exports to Germany, however, was that the Hungarian agricultural sector became a major creditor to the German economy due to the surplus in foreign trade caused by Germany’s reluctance to balance the clearing bill and, in fact, to pay its debts. The clearing imbalance was due to the fact that Germany significantly limited its exports of raw materials, as domestic demand increased in preparation for the war. While its share of Hungarian imports of raw materials and semi-finished goods averaged 26 percent between 1927 and 1933, it was only 12.9 percent in 1937.27

Figure 4. Changes in import between 1930 and 1939

Source: Based on the data from the MSK, New Series, vols. 81, 82, 84, 85, 95, 98, 101,

106, 109, and 111.

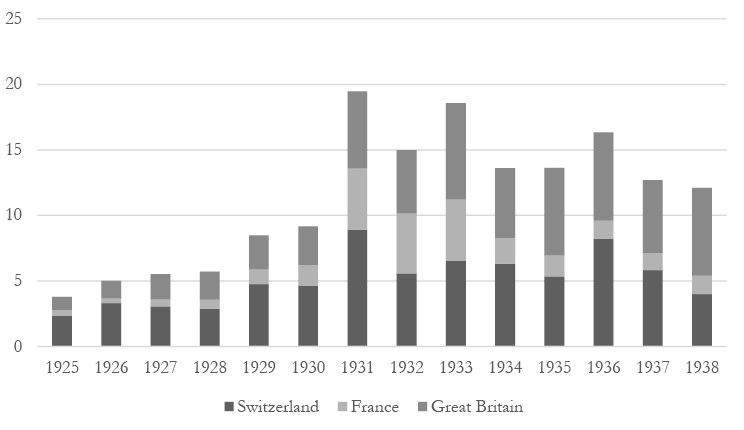

Figure 5. Distribution of agricultural exports to the most important countries between 1925 and 1937 as a percentage)

Source: Buzás, “Magyarország külkereskedelme,” 148.

The “missing” German products had to be imported from countries with freely transferrable currencies. This prevented exports to countries that would not have paid with hard currency. The Hungarian Governmentordered export companies to sell their products amounting to at least 20 percent of the value of their exports towards Germany in countries which made their payments in gold or hard, freely transferrable currencies. In order to achieve this aim, the government also provided proportional export subsidies to these companies. Export earnings had to be transferred to the Hungarian National Bank, which paid the companies the equivalent in pengős at the official exchange rate, while the Treasury added different premiums (according to each country and product), thus providing a considerable incentive for exporting companies. In 1935, premiums were set at 38 percent for “franc” exports (Belgium, France, Switzerland) and 50 percent for exports in a convertible foreign currency, irrespective of the nature of the products.

In 1936, the Price Compensation Fund (Árkiegyenlítő Alap) was created to support agricultural exports, and in its first year, 1.75 million pengős (306 thousand dollars) were allocated from the state budget and a further 1.228.315 pengős (215 thousand dollars) were made available thanks to the extra revenues from the high prices of exports to Germany. This enabled foreign exchange earnings of 10,891,504 pengős (1.9 million dollars) in 1936. This scheme also helped increase Hungarian exports to Great Britain and the United States in the second half of the 1930s.28 Exports to the United States increased in both 1936 and 1937 but then declined, while exports to Great Britain only rose until 1936, after which they started to decrease, with a dramatic drop by 1939.29

In the case of Hungary, the importance of agricultural exports in exchange for hard currency stemmed from the desire to reach an equilibrium in the balance of trade but even more so from the indebted country’s need to produce enough hard currency to finance the regular repayments of capital and interest. It is hardly a mere coincidence that the intentions of creditor countries began to appear behind the increase of sterling and dollar-based Hungarian exports. Thus, from the beginning of the Great Depression until the outbreak of World War II, important agricultural trade relations were established with countries that had previously functioned not as agricultural markets but as creditors for the Hungarian economy. Thus, Hungarian agricultural products with low added value could also help improve the country’s unstable financial situation (Fig. 6).30

Figure 6. Agricultural exports to Switzerland, France, and Great Britain (as a percentage).

Source: Gunst, “A magyar mezőgazdaság piacviszonyai,” 529.

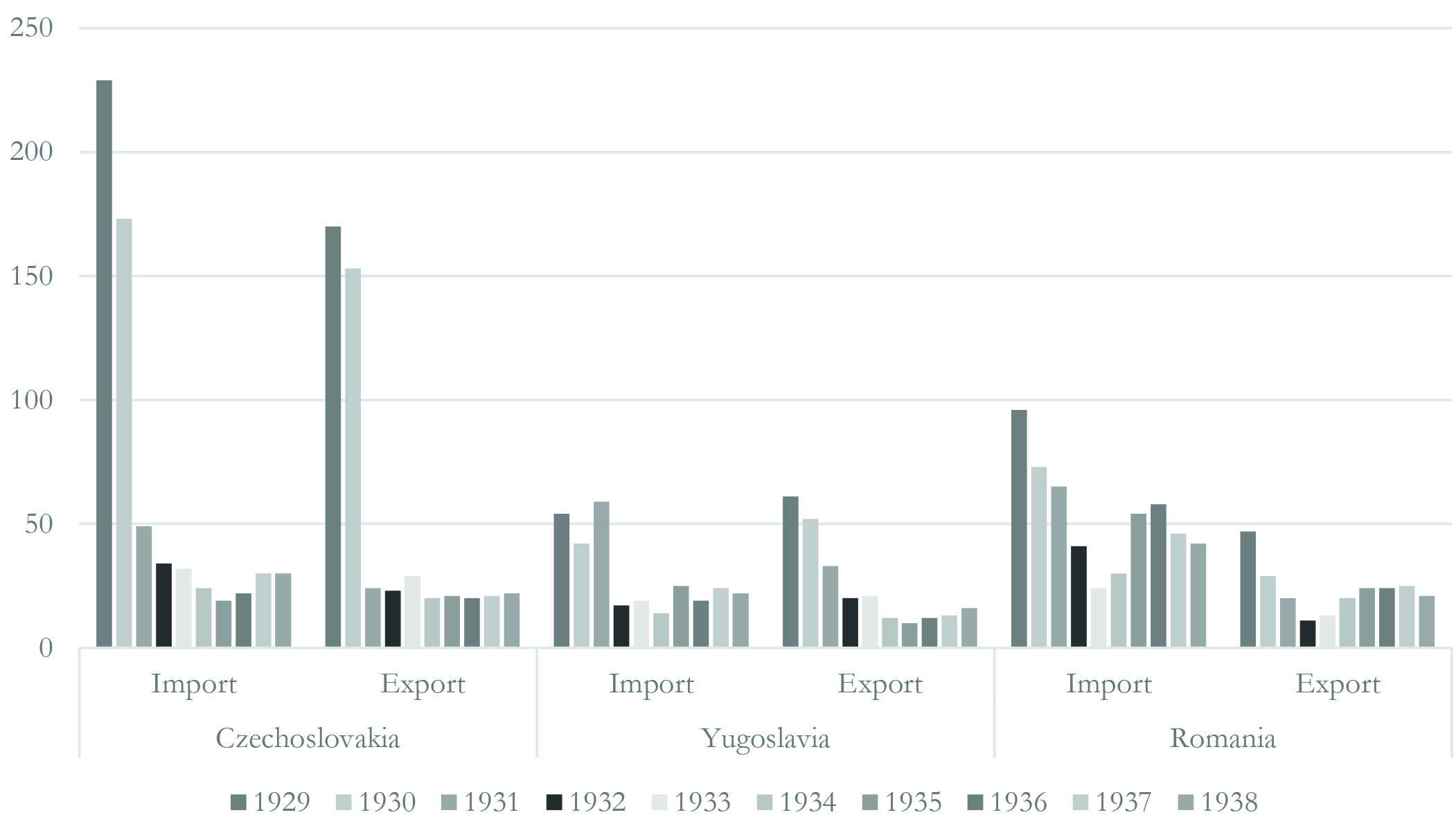

Figure 7. Hungary’s foreign trade with the Little Entente countries (in millions of pengő)

Source: Statisztikai Tudósító, March 29, 1939. 4.

When analyzing the changes in agricultural exports, one should note that after the sharp decline during the economic crisis, the country was able to increase its agricultural exports significantly, but there was a significant concentration of the markets, which led to increased dependence on the German Empire.

The decreasing diversification of the destination of Hungarian agricultural exports is reflected in the drastic decline of trade with the Little Ententecountries. In addition, the balance of Hungarian foreign trade with these countries ran deficits almost every year.

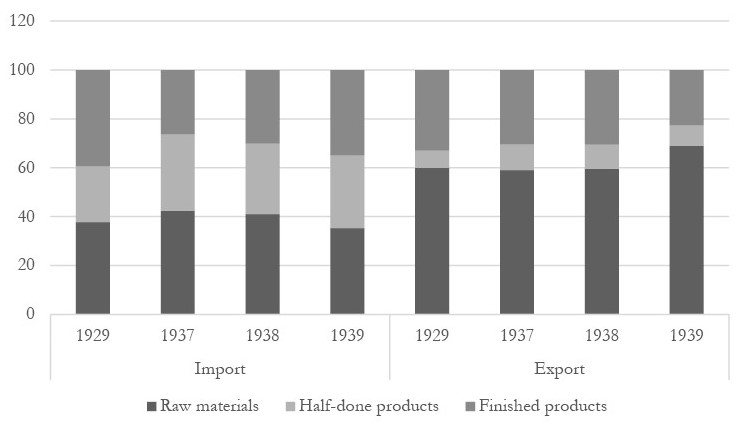

The Issue of Added Value

Another key explanation for the specificities of Hungarian exports lies in the product structure. If we look at the distribution of external trade by economic sector and by the degree of processing of goods,31 it is striking that between 1935 and 1939 the share of raw materials in Hungarian imports declined significantly (from 47.7 to 35.5 percent), while the share of finished goods continued to rise (from 25.5 to 35.4 percent).32

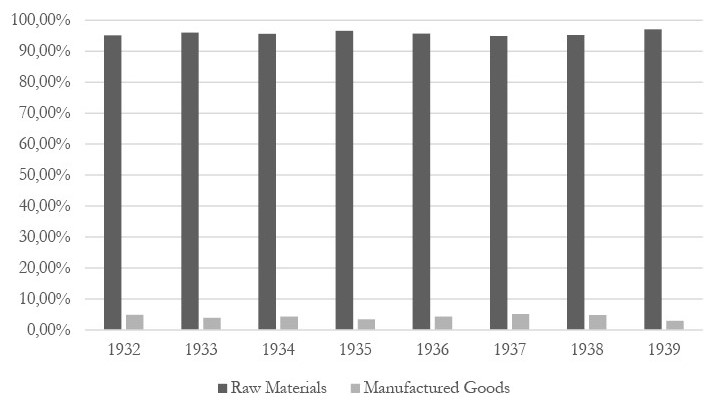

In the second half of the 1930s, the proportion of raw agricultural products in agricultural exports continued to rise from an already high level, while the share of processed food products declined (see Fig. 9). Exports of cereals and livestock increased, whereas higher value-added products, such as meat and meat products, as well as dairy products, experienced stagnation or decline.33

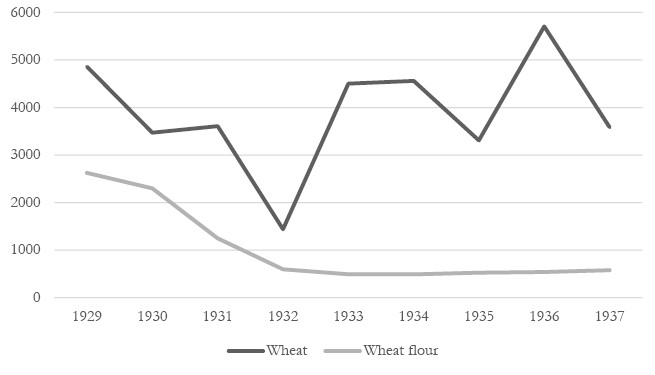

The changes in agricultural trade are even more noticeable when we break down the volume of exports by product group according to the degree of processing. The most important products in total exports were wheat and wheat flour.

One of the most striking changes in the 1930s was the sharp downward trend in flour exports. It also shows the profound changes that had taken place in international agricultural trade. These adverse changes cannot be attributed solely to the failings of Hungarian agricultural policy, as they also reflected the aspirations of the traditionally agricultural importing countries of the period. Namely, in an uncertain international environment, importing countries, motivated by growing protectionism, sought to reduce absolute exposure to strategic commodities by limiting their imports to the most profitable form possible. Thus, of course, they also secured the economic benefits of processing for their own country.

Figure 8. The distribution of foreign trade according to the degree of processing of the products (as a percentage)

Source: Based on Kereskedelmünk és iparunk az 1939. évben, 34.

Figure 9. Ratio of agricultural raw materials and manufactured goods in exports (as a percentage)

Source: MSK, New Series, vol. 81, 417; 82, MSK, New Series, vol. 81, 417; vol. 82, 406; vol. 84, 376; vol. 85, 374; vol. 95, 377; vol. 98, 371; vol. 101, 360; vol. 106, 305; vol. 109, 301; vol. 111, 291.

Figure 10. Development of wheat and wheat flour exports (in thousands of quintals)

Source: Own compilation based on Siegescu, “A magyar mezőgazdasági kiviteli tevékenység,” 551.

Summary

With the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, the traditional markets for Hungarian agricultural produce became less accessible. This in turn triggered a transformation in Hungarian trade policy. The disintegration of the single customs area, the lack of competitiveness, and the political tensions among the countries of the Danube Basin created permanent difficulties for Hungary in its efforts to bring its agricultural produce to international markets. Meanwhile, Hungary’s more industrialized neighbors, Austria and Czechoslovakia, fulfilled their import demands with lower-cost goods from overseas. In this period, the Hungarian milling industry, which in 1910 was still the second largest supplier of flour to the world market after the United States, had to dismantle much of its infrastructure because of market losses and underutilization.

These structural problems did not end until Germany, which had previously satisfied its immense demand for agricultural and food products with cheaper American goods, opened its vastly expanding markets to Hungarian agricultural products for economic and geopolitical reasons. However, due to clearing settlements, Germany’s increasing military preparedness, and the dominant party’s ability to assert its interests, Hungary, with its agricultural trade surplus, increasingly became a financial backer of the German Reich. Meanwhile, the financial pressure of repaying and servicing loans taken out in the 1920s, primarily from sources in Great Britain and the United States made agricultural exports to creditor countries necessary due to the lack of foreign currency. As a result, the role of agricultural exports in this trade relationship also became more significant, as creditors were eager to recover the funds they had previously lent their debtors. The government was ready to pay export premiums, which also contributed to maintaining the balance of Hungary’s payment situation.

The most important lesson of the period is that export-driven agriculture faced increasingly shifting and unpredictable demands. After the Great Depression this led to the realization that foreign market expansion could only be achieved within “imperial” relationships. It was the (geo)political (imperial) rationality of Germany on one hand and the financial rationality of Hungary’s creditors on the other which were able to provide an adequate market for Hungarian agricultural produce.

Bibliography

Primary sources

“A háború előtti Magyarország statisztikai adatai a megmaradt és elvesztett területek szerint részletezve” [Statistical data of pre-war Hungary broken down by remaining and lost territories]. Magyar Statisztikai Szemle,no. 7–8 (1923): 288–306.

Bende, István, ed. Magyar külkereskedelmi zsebkönyv [Hungarian foreign trade handbook], IV. Budapest: A M. Kir. Külkereskedelmi hivatal, 1938.

Kereskedelmünk és iparunk az 1939. évben [Hungarian trade and industry in 1939]. Budapest: Budapesti Kereskedelmi és Iparkamara, 1940.

Közgazdasági Értesítő, March 7, 1929.

Magyar Statisztikai Évkönyv. Új folyam 44, 1936[Hungarian statistical yearbook. New series 44. 1936]. Budapest: Athenaeum, 1937.

Magyar Statisztikai Évkönyv. Új folyam 47, 1939 [Hungarian statistical yearbook. New series 47. 1939]. Budapest: Athenaeum, 1940.

Mike, Gyula, ed. Magyar statisztikai zsebkönyv. VIII. évfolyam [Hungarian statistical handbook]. Budapest: A M. Kir. Külkereskedelmi hivatal, 1939.

MSK = Magyar Statisztikai Közlemények. Új sorozat [Hungarian Statistical Bulletin. New Series]. Budapest: Magyar Királyi Központi Statisztikai Hivatal, 1902—1942.

Secondary literature

Balkányi, Béla. “Magyarország mezőgazdasági kivitele” [Agricultural exports from Hungary]. Közgazdasági Szemle 7, no. 2 (1928): 134–57.

Buday, László. Magyarország küzdelmes évei [Hungary’s years of struggle]. Published privately. Budapest, 1923.

Buzás, József. Magyarország külkereskedelme 1919–1945 [Hungary’s foreign trade, 1919–1938]. Budapest: Közgazdasági és Jogi Könyvkiadó, 1961.

Eckhart, Ferenc. A magyar közgazdaság száz éve 1841–1941 [One hundred years of Hungarian economics, 1841–1941]. Budapest, 1941.

Fejes, Judit. “A magyar–német gazdasági és politikai kapcsolatok kérdéséhez az 1920-as–1930-as évek fordulóján” [Hungarian-German economic and political relations at the turn of the 1920s and 1930s]. Történelmi Szemle 19, no. 3 (1976): 361–84.

Föglein, Gizella. “Tradíció és modernizáció a magyar mezőgazdaság utóbbi másfél évszázadában” [Tradition and modernization in the last 150 years of Hungarian Agriculture]. Múltunk 49, no. 3 (2004): 256–63.

Gunst, Péter. “A magyar mezőgazdaság piacviszonyai és a német piac az 1920–30-as években” [Market relations of Hungarian agriculture and the German market in the 1920s and 1930s]. Századok 118, no. 3 (1984): 513–30.

Gunst, Péter. Magyarország gazdaságtörténete (1914–1989) [An economic history of Hungary, 1914–1989]. Budapest: Nemzeti Tankönyvkiadó, 1996.

Ihrig, Károly. Szövetkezetek a közgazdaságban [Cooperatives in economics]. Budapest, 1937.

Klement, Judit. “Budapest és a malmok, 1841–2008” [Budapest and the mills]. Történelmi Szemle 65, no. 1 (2023): 155–67.

Matlekovits, Sándor. Vámpolitika és vámtarifa [Customs policy and customs tariffs]. Budapest, 1923.

Mózes, Mihály. Agrárfejlődés Erdélyben, 1867–1918. Eger: Eszterházy Károly Főiskola Líceum Kiadó, 2009.

[Niederhauser, Emil.] “A Magyar–Csehszlovák Történész Vegyesbizottság tudományos ülésszaka” [Report on the scientific session of the Hungarian-Czechoslovak Joint Committee of Historians]. Századok 110, no. 6 (1970): 1106–20.

Orosz, István. “A modernizációs kísérletek főbb szakaszai a magyar mezőgazdaságban a XIX–XX. században” [The main phases of modernization experiments in Hungarian agriculture in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries]. Múltunk 48, no. 2 (2003): 231–58.

Pál, György, and István Salánki. “A cukoripar fejlődése” [The development of the sugar industry]. Élelmezési Ipar 40, no. 9 (1986): 327–33.

Rege, Károly. “Magyarország búzatermelésének 100 éves áralakulása és termelési költsége” [100-year price evolution and the costs of production of wheat in Hungary]. Magyar Statisztikai Szemle no. 6 (1934): 460–78.

Siegescu, Miklós. “A magyar mezőgazdasági kiviteli tevékenység az 1929–1937. években” [Hungarian agricultural exports in 1929–1937]. Magyar Gazdák Szemléje 43, no. 12 (1938): 539–52.

Schlett, András. “Agrár-közgazdaságtan a két világháború között” [Agricultural economics in the interwar period]. Heller Farkas Füzetek 1, no. 1 (2003): 17–28.

Schlett, András. “Megkésettség – nyitottság – kettős erőtér: Közgazdászok az agrárpolitika szolgálatában a két világháború közötti Magyarországon” [Belatedness – Openness – Converging Influences: Economists in the service of agricultural policy in interwar Hungary]. Agrártörténeti Szemle 50, no. 1–4 (2009): 217–30.

Szegő, Sándor. “A magyar cukoripar gazdaságtörténetéből VII.” [The economic history of the Hungarian sugar industry]. Cukoripar 28, no. 1 (1975): 31–33.

Szőnyi, Gyula. “Gabonaárak a XVIII. század vége óta” [Cereal prices since the end of the eighteenth century]. Magyar Statisztikai Szemle, no. 3 (1935): 123–54.

Szuhay, Miklós. Állami beavatkozás és a magyar mezőgazdaság az 1930-as években [State intervention and Hungarian agriculture in the 1930s]. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, 1962.

Vajda, Ödön. “Cukoripar” [The sugar industry]. Magyar Statisztikai Szemle 17, no. 6(1939): 667–71.

Zeidler, Miklós. “Társadalom és gazdaság Trianon után” [Society and economy after Trianon]. Limes – Tudományos Szemle 15, no. 2 (2002): 5–25.

1 Siegescu, “A magyar mezőgazdasági kiviteli,” 538.

2 Buday, Magyarország küzdelmes évei, 12.

3 Based on the data from MSK, New Series, vol. 56.

4 Zeidler, “Társadalom és gazdaság,” 11; Gunst, Magyarország gazdaságtörténete, 40.

5 Mózes, Agrárfejlődés, 185.

6 Föglein, “Tradíció és modernizáció,” 259.

7 Schlett, “Agrár-közgazdaságtan,” 18–19.

8 Orosz, “A modernizációs kísérletek,” 248.

9 Gunst, “A magyar mezőgazdaság piacviszonyai,” 517–18.

10 Zeidler, “Társadalom és gazdaság,” 13–14.

11 Ibid.

12 Balkányi, “Magyarország mezőgazdasági kivitele,” 138–39.

13 See Klement, “Budapest és a malmok.”

14 The milling trade in the milling industry refers to the practice where mills process foreign raw materials, such as grain imported from abroad, and then export the resulting flour or other processed products. This process was common in Central Europe, particularly in countries like Hungary, where the milling industry played a significant role in the economy. One of the main advantages of the milling trade is that it allows the country to export processed products with greater added value instead of raw grain. This practice previously contributed to the development of the milling industry, and also played an important role in international trade.

15 Közgazdasági Értesítő, March 7, 1929, 2–3.

16 Eckhart, A magyar közgazdaság száz éve, 274.

17 Szegő, “A magyar cukoripar,” 31; Vajda, “Cukoripar,” 667.

18 Pál and Salánki, “A cukoripar fejlődése,” 328.

19 Buzás, “Magyarország külkereskedelme,” 148.

20 Matlekovits, Vámpolitika és vámtarifa, 51.

21 “A Magyar–Csehszlovák Vegyesbizottság,” 1107.

22 MSK, New Series, vol. 84, 21.

23 MSK, New Series, vol. 82, 51.

24 Ihrig, A szövetkezetek, part 4, chapter 4.

25 Schlett, “Megkésettség,” 219.

26 Fejes, “A magyar–német gazdasági,” 370–71.

27 Bende, Magyar Külkereskedelmi Zsebkönyv, 1938, 72.

28 Szuhay, Állami beavatkozás.

29 Based on the data from MSK, New Series, vols. 85, 95, 98, 101, 106, 109, and 111.

30 Siegescu, “A magyar mezőgazdasági kiviteli,” 548.

31 It is important to note that the Hungarian Central Statistical Office (KSH) applies two different approaches in classifying raw materials, semi-finished products, and finished goods: one based on production and the other on usage. In this article, I follow the production-based approach and categorize the products accordingly.

32 Kereskedelmünk és iparunk az 1939. évben, 34.

33 Bede, Magyar Külkereskedelmi Zsebkönyv, 1938, 26, 32–33.