HHR_2025_4_Toncich

“We Cannot See Ourselves Reflected in All Italian Institutions”: Reform Psychiatry, Habsburg Legacies, and Identity-Making in the Upper Adriatic Area*

Francesco Toncich

Department of Humanities, University of Trieste

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Hungarian Historical Review Volume 14 Issue 4 (2025): 615-654 DOI 10.38145/2025.4.615

This article analyses the development of criticisms of psychiatric institutions and restraint-based treatments for psychiatric and neurological patients as a foundation for identity-making processes in the Upper Adriatic from a long-term perspective. Between the 1960s and 1980s, the region, which was once part of the Habsburg Empire but was by then divided between Italy and Yugoslavia, became a hub for the deinstitutionalization of a psychiatric system still burdened by its Fascist legacy. This reform fostered renewed identity-making within local society, rooted in early Habsburg-era psychiatry. As early as the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Austrian psychiatry in this region had embraced non-restraint and outpatient therapies based on the liberal idea of modernity, which exerted a lasting influence on the psychiatric institutions in Trieste and Gorizia. World War I and the dissolution of the Habsburg Monarchy brought Italian rule, under which Fascism transformed psychiatry into a tool of repression, eradicating alternative treatments and creating a clash between psychiatric cultures. This clash became foundational to the development of an identitarian model, rooted in Habsburg nostalgia and a presumed local “tradition” of alternative psychiatry during periods of profound crisis and transformation, particularly the reforms in the institutional world of psychiatry in the 1960s–70s.

Keywords: deinstitutionalization of psychiatry, non-restraint, Upper Adriatic region, Habsburg psychiatry, Fascist psychiatry

Introduction

Can psychiatry and criticism of psychiatry contribute to shaping forms of social, political, and cultural self-identification over the long term? This article explores this question by examining the history of psychiatry and reforms in the field of psychiatry within the context of the Upper Adriatic from the mid-nineteenth to the twentieth century, focusing on the region’s two principal psychiatric hospitals in Trieste and Gorizia.

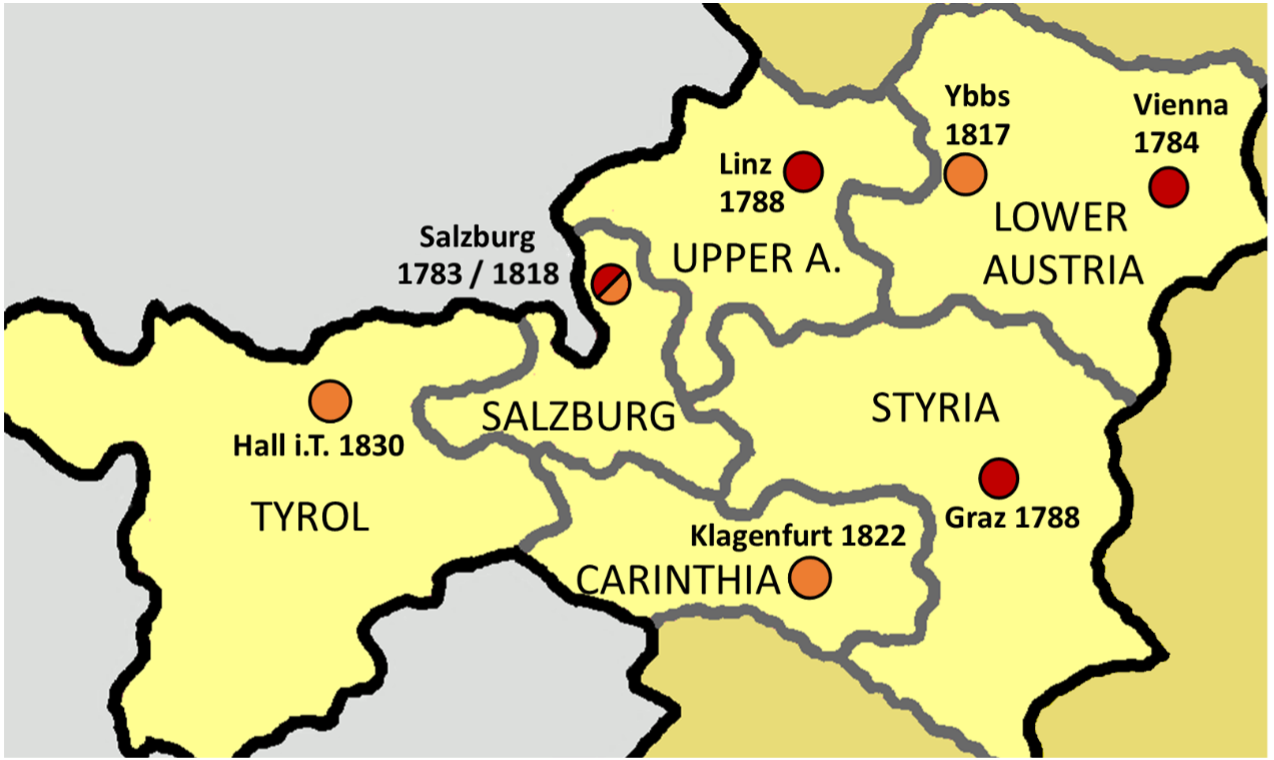

A long-term perspective has proven valuable in international psychiatric historiography, particularly in revealing the interplay between continuity and disruption in institutional practices, especially concerning the balance between constraint and non-restraint psychiatry.1 Following this approach, this study aims to investigate a largely overlooked aspect of the region’s psychiatric history, situating it within the broader debate on the “Habsburg legacies” after World War I.2 Established in the early twentieth century by Habsburg authorities, both asylums were among the most progressive in the Austrian network, promoting outpatient care and non-restraint therapies.3 The collapse of the Habsburg Empire marked a traumatic transition, as psychiatric institutions were absorbed into the Italian (from 1922, Fascist) system, dismantling the experimental foundations of the practice and relegating these institutions to the margins of a centralized national model. After World War II, however, they reemerged as pioneering sites of radical deinstitutionalizing reforms of psychiatric care in the 1960s and 1970s.4 These radical transformations unfolded in a porous borderland, shaped by a multilingual, cross-border society during a period of détente and the gradual fall of the Iron Curtain.5

Historiography has largely focused on the repeated geopolitical upheavals within this macro-region. Since the end of World War I, the Upper Adriatic has been a complex geopolitical, cultural, and ideological borderland. Formerly part of the Habsburg Empire’s Littoral (Küstenland), it encompassed Trieste, Gorizia, and the Margraviate of Istria. The region was multilingual and multicultural, with Italian, Slovenian, Croatian, and German widely spoken, and it was marked by socioeconomic contrasts between rural areas and urban centers.6 The Great War and the collapse of the empire ushered in a prolonged period of instability, with shifting borders and statehoods from 1918 to 1991, a condition that prompted scholars to refer to the region as a “crisis hotspot.”7 These upheavals shaped psychiatry not only as a medical discipline but also as part of a broader cultural and social system.8 This article adopts a long-term perspective to examine how diverse “medical/psychiatric cultures” shaped self-identification within the medical profession and local communities from the Habsburg era onward. It highlights continuities and ruptures in the enduring conflict between containment psychiatry and non-restraint approaches and in the ways in which medical and civil societies characterized and perceived themselves. Debates on repressive psychiatry and open-door, outpatient treatments began well before World War I and persisted despite the Fascist era of control and repression, resurfacing in later decades after World War II. Although psychiatry played a central role in the region’s history, historiography has largely treated it as marginal, underestimating its impact on cultural and social structures, even as it constituted a significant element of both continuity and change.

By considering these questions from the critical perspective of entangled and transnational history,9 this study moves beyond national historiographies to challenge the notion of distinct psychiatric “traditions” shaped by present-day nation states, which repeatedly conceive the evolution of psychiatry exclusively within national frameworks, thereby overshadowing both transnational and local dimensions of its developments.10 Instead, it highlights the dynamics and involvement of local innovations and their persistence over decades of geopolitical change. Recent scholarship has emphasized the profound social and cultural influence of psychiatric networks within the late Habsburg Empire, particularly the distinctive dialogue between asylum and society, and the deep embedment of these networks within the local social and cultural fabric.11 Historiography has also pointed to continuities in the field of psychiatry after the dissolution of the empire, exploring the formation and endurance of a shared Habsburg “psychiatric landscape,” despite the post-World War I fragmentation of the Central European macro-region.12 Nonetheless, research on psychiatry in the Upper Adriatic remains fragmented and predominantly shaped by postwar national and ethnocentric frameworks, which limit a fuller understanding of the multicultural and transnational character of Habsburg psychiatry and its legacies.13

A long-term horizontal approach is crucial if we seek to offer a nuanced analysis of enduring psychiatric structures, practices, and medical cultures, but it must also intersect with a vertical perspective that examines the interplay between psychiatric and administrative structures at both the central and peripheral levels.14 Recent research has challenged Vienna’s dominance in the development of Central European psychiatry, highlighting the importance of decentralized psychiatric networks in which peripheral regions developed autonomous systems for mental health care within the broader imperial framework.15 This perspective reveals parallel developments across the Habsburg psychiatric landscape and also highlights the persistence of practices and continuities in the post-Habsburg era, particularly in those same peripheries. These peripheral areas were shaped by the characteristic Habsburg federalist and local-autonomist structure, as well as by the formation of everyday habitus and mentalities that became deeply embedded within the social, political, and cultural frameworks of local societies, even over the long term.16 These dynamics helped shape evolving psychiatric approaches and foster enduring self-identifications in regions with autonomist traditions. This is evident in the Upper Adriatic, where, despite rapid border and regime changes from 1918 to 1975, forms of medical culture remained rooted in psychiatry and criticisms of the field of psychiatry and played a central role in a broader process of self-identification.

Post-World War II Psychiatric Reform and “Habsburg nostalgia”:

Rediscovering or Reinvigorating a Psychiatric “Tradition”?

Between the 1960s and 1970s, the northeastern Italian region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia became a key center of the international radical psychiatric reform and deinstitutionalization movements, with the asylums in Gorizia and Trieste at the forefront. Led by Franco Basaglia and his wife and collaborator Franca Ongaro, the psychiatric teams implemented radical open-door therapeutic approaches inspired by experiments such as Dingleton, Villa 21, and Kingsley Hall.17 This deinstitutionalizing experiment, first in Gorizia (1961–1970), then in Trieste (1971–1980), emerged from a peripheral region along the Iron Curtain,18 sparking intense social and cultural debate both in Italy and abroad. The reform enshrined patients’ human and civil rights, protected them from abuse, and promoted outpatient care. It culminated in the passage of Law no. 180 by the Italian parliament in 1978.19 This legal recognition led to the gradual dismantlement of a repressive psychiatric system still marked by eugenic-biologistic legacies, replacing it with a decentralized, community-based model aimed at the social reintegration of individuals with mental health issues.20

In June 1974, the first “Conference of Democratic Psychiatry” was held in Gorizia, bringing together key figures involved in psychiatric reform in Italy and abroad. At the time, Franco Basaglia had been director of the Trieste asylum for three years and was already in the process of dismantling it.21 The conference aimed to draft a manifesto calling for the closure of psychiatric hospitals and the transformation of care in Italy, although it also provoked broader international interest across Europe, as well as North and South America. 22 Gorizia was chosen as the venue due to its role as the first experimental site of reform a decade earlier. This small northeastern Italian town was split after World War II by the border between the Italian Republic and the Yugoslav Federation. In accordance with the terms of the 1947 Paris Peace Treaty, the border between Italy and Yugoslavia (and thus, the Iron Curtain) ran through its center, dividing it into Italian Gorizia and Yugoslav Nova Gorica. The Gorizia asylum, under Italian control, stood with its eastern wall symbolically aligned with both the state border and the Iron Curtain.23

Among the many national and international attendees (primarily psychiatrists, physicians, and psychologists) was Silvino Poletto, a prominent figure in both the regional and national Italian Communist Party.24 During the conference, Poletto delivered a speech emphasizing the broader significance of the psychiatric reform initiated by the “Basaglia team” at the Gorizia asylum. However, his address took an unexpectedly local-historical and “identitarian” turn, linking the present with the past of these border territories through the concept of “tradition.” In his speech, he characterized the province of Gorizia as a key historical site for critical assessments of and opposition to repressive containment practices in psychiatry:

One of the qualities of the “Basaglia School” (by which I mean the group of those involved in the association of social and psychiatric workers – practitioners, assistants, and so on) is that it taught us the importance of returning to our history and learning how to read into traditions. In the traditions of the province of Gorizia, there was a doctor (Luigi Pontoni, A.N.) who, in 1901, 73 years ago (at that time Austria-Hungary was in power, though that matters less), wrote something I am going to read to you. It will show how, in the Gorizia area, Basaglia’s team was able to succeed and also knew how to connect with a tradition that stemmed from the Vienna school. […] A concept was introduced: that mental alienation is an illness, and that the person affected, like any other patient, has the right to receive care without any restriction of personal freedom, except where absolutely necessary in cases of urgent need. This principle would later inspire the modern open-door asylum and find fuller expression in the agricultural colonies attached to the hospital. This happened in 1901! A tradition worth remembering. 70 years of psychiatric practice have contributed to a rich heritage at the local, regional, and national levels.25

This account, offered by a non-specialist “insider,” presents an alternative perspective on the classic historiographical narrative of the reforms in the field of psychiatry in Italy in the 1960s. The dominant narrative tends to frame these revolutionary initiatives through national lenses, focusing on post-World War II Italian psychiatry, Basaglia’s personal trajectory, and the team’s involvement in international networks. However, in this portrayal, the local context is often overlooked or obscured, with the histories of both hospitals either omitted or only briefly mentioned.26

Poletto’s speech introduced a valuable shift in perspective. The territory, he suggested, was not merely a testing ground for external, global theories. Rather, it was a historically fertile site with its own cultural heritage of critical thought on mental health and psychiatry and early practices of non-restraint and patient rights as part of a local “tradition.” Framing the reform within the region’s unique context, Poletto evoked its Habsburg and Central European psychiatric roots, in contrast to the narrow focus on the Italian national perspective. The imaginary of the “Vienna School,” rooted in a long-standing tradition of peregrinatio medica undertaken by generations of physicians from all the imperial crownlands (including those from Trieste, Gorizia, and the Austrian Littoral),27 emerged as a historical model linked to humanitarianism and, above all, modernity during the ambivalent fin-de-siècle period.28 It formed a dialogical historical bridge between the local territory, transnational space, psychiatry, and identity.

The key word used by Poletto in his programmatic speech is “tradition,” a term introduced at a moment of radical paradigm change in psychiatric theory and practice. Poletto employed it in a decidedly essentialist way, seeking to trace an objective and direct line of development from Habsburg times to his own day. Nevertheless, this strong emphasis on “tradition” in psychiatric practice as a marker of self-identification appears, in fact, to be part of a much more complex cultural and social process: it cannot simply be reduced to something transmitted across generations that conditions the experiences and perceptions of individuals or communities.29 Rather, it must be understood as a construct continually reevaluated, reexamined, and renegotiated by the very actors who carry it forward, particularly during moments of crisis, when new ideas and paradigms emerge that challenge and conflict with established beliefs and habits, prompting actors, through their agency, to call into question and rethink the inherited construct.30 “Tradition” is thus intrinsically bound both to the concept of “heritage,” a central notion in studies of the historical evolution of territories in the former Habsburg space, and, at the same time, to a continuous process of negotiation and adaptation.

This complex identitarian discourse did not emerge in a vacuum. Poletto’s cultural archaeology of psychiatry and reformism formed part of a broader local movement, which rethought self-identification by drawing on a past that resisted seamless integration into an absolute national (Italian) narrative. Instead, it resonated with a post-World War II revival of “Habsburg nostalgia.”31 The radical psychiatric reforms in Gorizia and Trieste had a profound impact beyond medicine, influencing the countercultural movements of 1968 and offering a foundation for broader cultural, social, and political self-definition.32 Local practitioners involved in the deinstitutionalization process in the Upper Adriatic began revisiting the region’s psychiatric history, reflecting on the origins of local institutions under the Habsburg Monarchy, and explicitly engaging with imperial legacies.33 This revival took place within the specific geopolitical and historical framework of the Alps-Adriatic détente.

Over the course of these decades, the Italian Julian March region, particularly the cities Trieste and Gorizia, underwent a period of crisis and transformation due to various factors.34 After its incorporation into Italy following World War I, the region, once a strategic outlet of the Habsburg Empire, entered a prolonged phase of decline. Trieste, in particular, was reduced from the principal commercial port of a multinational empire to a peripheral harbor of a nation state. After World War II, the new border between Italy and Yugoslavia cut Trieste and Gorizia off from their historical economic hinterlands, and the 1975 Treaty of Osimo, which formalized the post-World War II border, ultimately guaranteed the region’s geopolitical and economical marginalization. Gorizia was divided by the Iron Curtain, and Trieste suffered deep economic difficulties, exacerbated by industrial and shipbuilding reforms in the 1960s that dismantled its historic maritime infrastructure.35 A deep local crisis of repositioning affected politics, society, and professional spheres, including the medical-psychiatric field. In response to the sweeping transformations of the 1950s–1970s, older forms of localist, regionalist, and municipalist self-identification resurfaced, especially in the former free port city of Trieste.36 Rooted in the complex and diversified structure of the Habsburg Monarchy,37 these tendencies reemerged just as the Italian state was formally acknowledging the region’s historical distinctiveness by establishing Friuli-Venezia Giulia as an autonomous region in 1963.38

At the same time, the Upper Adriatic entered a new phase of reorganization, coinciding with the onset of détente between the Cold War blocs and the rise of transnational cooperation among countries that had once been part of the Habsburg Empire. In the Alps-Adriatic macro-region, détente involved reactivating former Habsburg-era channels and structures. The “Alpe-Adria Working Community” emerged, fostering political, economic, and cultural collaboration, including cross-border healthcare initiatives and efforts to revive networks disrupted by postwar geopolitical divisions.39 In this unique context, the psychiatric reforms in Gorizia and Trieste were interconnected with vibrant exchanges involving psychiatrists and institutions from former Habsburg successor states, including Austria, Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia. Central and Southeastern European psychiatrists, such as Vladimir Hudolin and Miroslav Plzák, engaged in close transnational collaboration and dialogue with Basaglia’s team in Gorizia and Trieste.40

A complex and enduring process of identity redefinition began in the 1960s, centered on the “rediscovery” of a mythical imperial past. Trieste’s intellectual class began reviving a Central European heritage and constructing a broader identity discourse alongside notions of Italian national belonging.41 Historical and literary scholarship increasingly explored the distinct position of the Upper Adriatic and Trieste, moving beyond nationalist, ethnocentric narratives that had fragmented the region into a mosaic of allegedly conflicting ethnocentric identities. Claudio Magris’s 1963 study on the Habsburg myth in Austrian literature and Arduino Agnelli’s 1971 work on the genesis of Mitteleuropa were pivotal examples of a local cultural canon that reconnected Trieste and the region with the Habsburg legacy, Vienna, and the Monarchy’s former territories.42 This shift was also reflected in broader international scholarship (exemplified for instance by the writings of American historian Dennison Rusinow), which in the 1960s began examining the persistence of “Austrian heritage” in the Italian borderlands that had once been part of the Danube monarchy.43

The narrative evoking the innovative spirit of the “Golden Habsburg years” contrasted sharply with the contemporary decline and marginalization of the Upper Adriatic as a militarized periphery.44 A yearning for the multicultural, cosmopolitan, and modernist character of Habsburg Trieste became intertwined with renewed interest in psychiatry, psychoanalysis, and mental health. Central to this was the rediscovery of the region’s Habsburg-Viennese medical heritage, which positioned Trieste and the Upper Adriatic as a transnational “bridge” between Central Europe and Italy in transferring innovations in the medical and “psy” disciplines from the Viennese modernist center at the fin de siècle. In the early 1970s, medical historian Loris Premuda portrayed Trieste’s bilingual Italian- and German-speaking doctors as symbols of this bridging role.45 By connecting Trieste to Vienna rather than Rome, Premuda framed the region as part of the Central European path to modernity and promoted a narrative of crisis recovery and transnational identity. The reference to the prestigious “Viennese school” thus became a strategic means of reclaiming Trieste’s historical centrality, echoed in Silvino Poletto’s address, as Italy confronted the burdens of its past and the legacy of fascism.

During the experiments in Gorizia and Trieste, the local intellectual class began constructing a cultural canon around mental health and the “unconscious,” mythologizing Trieste as a multicultural city tied to modern and alternative mental health care: a city in crisis reimagined itself through the lens of the “psy”

sciences. In 1968, Giorgio Voghera, a Jewish writer from Trieste, published his memoirs, blending his childhood experiences with the rise of psychoanalysis within Trieste’s social fabric and intelligentsia and portraying the Adriatic city as a distinctive “city of psychoanalysis.”46 Psychoanalysis, introspective psychology, alternative mental care methods, and Habsburg imperial modernity, alongside pre-Holocaust Central European Jewish identity, were also explored in the seminal 1981 book by historians Angelo Ara and Claudio Magris on Habsburg Trieste and its multicultural identity.47 These works helped shape a powerful cultural canon for local self-identification, grounded in the revival of Habsburg Trieste as the “first Italian city of psychoanalysis,” a title tied to the pioneering contributions of local psychiatrists Edoardo Weiss and Vittorio Benussi, who played key roles in spreading Austrian psychoanalytic theories and practices in Italy.48 Crowning this mythologization is the 1978 film La città di Zeno (The City of Zeno) by Trieste director Franco Giraldi, based on the 1923 novel La coscienza di Zeno (Zeno’s Conscience) by Italo Svevo, the penname of Trieste Jewish writer Hector/Ettore Schmitz.49 The novel presents the psychoanalytic diary of Zeno Cosini, a denizen of Trieste who suffers from “neurasthenia” and seeks treatment from local psychoanalysts during the final years of Habsburg rule and the early days of Italian governance.50 The film links present-day, declining Trieste to its vibrant Habsburg past through the bright influence of psychoanalysis in the Adriatic port city. In this construction of a historical, localist mythology around the “psy” concept, Giraldi included interviews with Franco Basaglia and other figures from the local intelligentsia, further legitimizing the process of self-identification.

The psychiatric reform movement in Trieste and Gorizia in the 1960s and 1970s was more than medical reform. It became, quite unintentionally, part of a broader process of local self-identification. Deinstitutionalization brought together scientists, policymakers, and cultural figures in a shared space shaped by the region’s complex past. In this context, Communist deputy Silvino Poletto’s 1974 speech at the “Democratic Psychiatry” convention in Gorizia stands out.

Referring to Habsburg Gorizia, Habsburg physician Luigi Pontoni, and the region’s tradition of humane care, Poletto contrasted the traditions of the city and region with fascist authoritarianism and postwar traumas of border changes and identity crisis. Beyond nostalgia, his reference to the Habsburg past was a deliberate assertion of regional distinctiveness and a demand for recognition of the prominent figures of the region as active contributors to a world in transformation.

The Origins of Reform Psychiatry and Non-Restraint

in the Habsburg Littoral

The lunatic is merely a sick person who can be cured. Dementia is sometimes a temporary condition. Delusion, whether arising from the dark oblivion of sorrow that causes it or under the influence of specific treatments, can subside and even dissipate. The alienist, upon receiving the afflicted individual into his asylum, does not lose hope of restoring his or her reason. However, to care for these patients effectively, we must feel compassion for them. We must be moved by their pain and suffering. […] Today, we are no longer moved by their pain. The mathematical positivism of our time seeks to demonstrate, with the utmost precision, that there is no muscle more useless or dangerous than the heart. […] In this way, we have entered the realm of egoism, where the rigid tones of calculation and speculation prevail.51

In his 1901 essay, Gorizian physician Luigi Pontoni set out his vision for the new psychiatric hospital in Gorizia. He emphasized the need to move beyond rigid positivism in psychiatry and advocated a new doctor–patient relationship as the foundation of a more humane and effective approach to psychiatric care. 70 years later, Silvino Poletto could easily have encountered such texts in the Provincial Library of Gorizia, where Pontoni had outlined forward-thinking approaches to the treatment of mental illness.

Luigi Pontoni, a prominent figure in the local Habsburg medical community, trained at the University of Vienna and served as head physician at the Civic Female Hospital in Gorizia.52 He stood out as a strong advocate

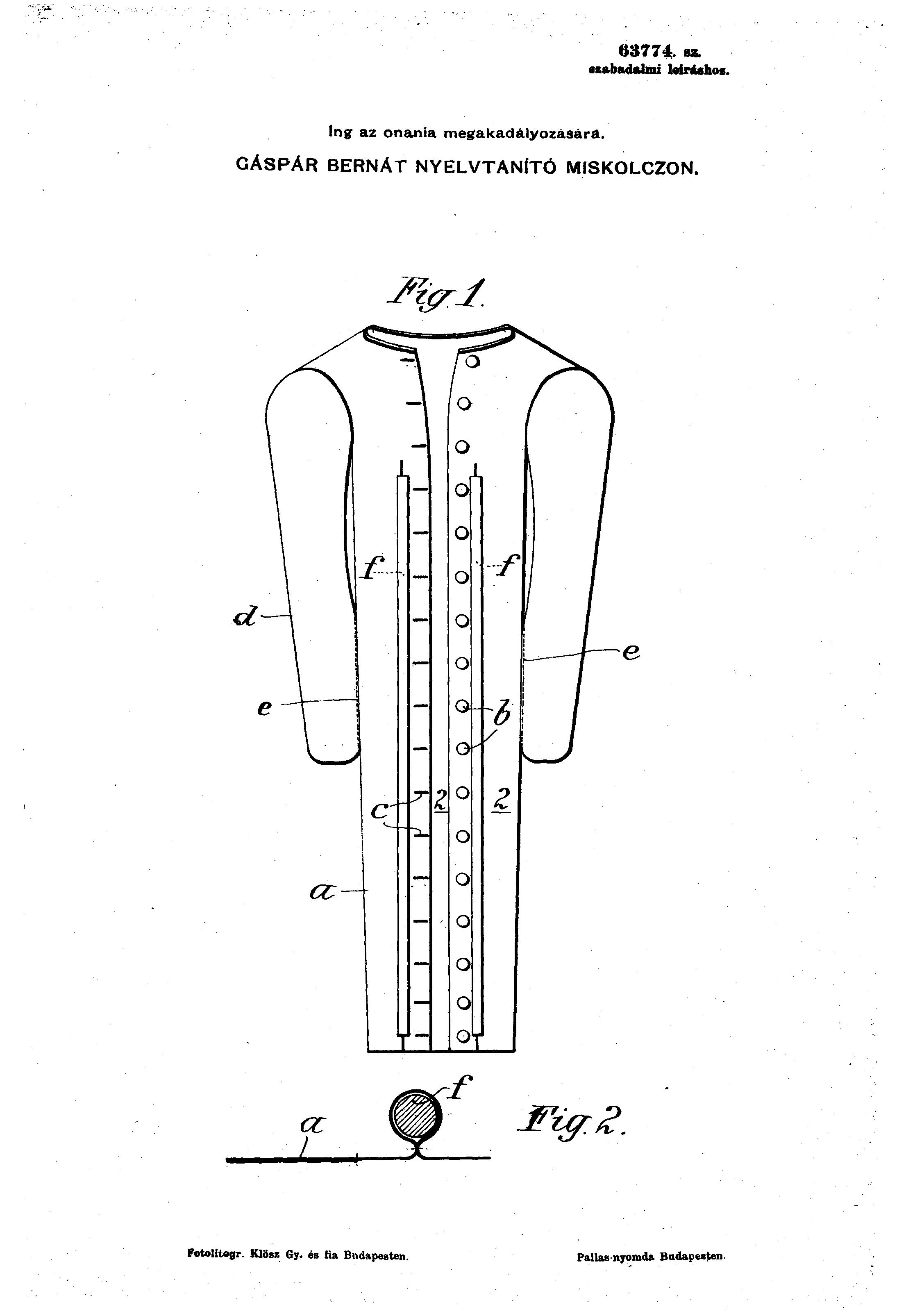

for psychiatric reform, promoting new kinds of psychiatric hospitals based on modern scientific principles. Inspired by the open-door policies and work therapy used in German asylums like Alt-Scherbitz, his motto was “Freedom and work.”53 Although Pontoni later criticized the slow progress of Austrian psychiatry compared to its German counterpart,54 he included detailed maps of German and Austrian institutions like those in Danzig or Vienna in his efforts to persuade the Gorizian provincial government and the Triestine Lieutenancy to adopt the pavilion model.55 Pontoni’s advocacy for modern asylum design based on international and imperial models shows how psychiatry had become a major public issue by the turn of the century, reaching beyond political and social elites. His writings reflect the active debate on psychiatric reform in the Littoral, which involved both professionals and the bourgeoisie from the 1860s onward. Criticism of forced custodial psychiatry and support for more humane, non-restraint approaches aligned with the liberal bourgeois aspirations for broader social and cultural reform.

The library of the former Trieste Medical Association, now part of the university’s medical faculty library, contains scientific and popular texts from the turn of the twentieth century that sharply criticized inhumane psychiatric practices and called for radical reform or even the closure of psychiatric institutions.56 This collection reflects the active involvement of the medical-psychiatric community of Trieste in the broader debate on patients’ rights and psychiatric reform, which, from the 1890s to World War I, extended beyond Vienna into the empire’s provinces. Psychiatry in Gorizia and Trieste was part of a larger Habsburg network, influenced by reformist movements which challenged restrictive practices. Shaped by social and political discussions on patients’ rights, local psychiatric networks mirrored trends in Austrian psychiatry and politics, culminating in the tardive 1916 imperial ordinance on interdiction.57 The involvement of expert psychiatrists, political figures, and public debates, alongside the construction of two of the most modern hospitals in the empire outside the imperial capital,58 highlights the dynamic mobilization within the

Littoral’s medical, political, and bourgeois circles and the region’s prominent role within the broader imperial network.59

Psychiatry in the Littoral region during the second half of the nineteenth century was in dire need of radical reform. Since 1785, only one psychiatric asylum, the Saint Justus hospital, had operated in the entire Littoral crownland. Located in the medieval district of Trieste, it housed patients from the city, Istria, and Gorizia-Gradisca.60 By the mid-nineteenth century, the facility was grossly inadequate, occupying the former episcopal seat of Trieste. The few surviving patient records from the 1840s–1860s show widespread use of violent restraints, including straitjackets and chains.61 From the 1860s onward, political authorities in the Littoral began to recognize the rising prevalence of mental disorders. They attributed this rise to new political and socioeconomic factors or simply the increased recognition of such disorders due to the professionalization of psychiatry. In August 1862, Trieste’s mayor, Stefano de Conti, expressed his concerns to the Littoral’s Lieutenant, Friedrich Moritz von Burger, about the state of psychiatry in the province, stating that, “the need for an asylum that met the requirements of this province and aligned with the progress of psychiatry had long been recognized.”62 A new psychiatry “would meet the most pressing needs of the present as well as those of the not-too-distant future, considering that the number of in-patients in our asylum has doubled in the last decade and that, since 1849 – as in many other parts of the Empire, and unfortunately in this region as well – the number of cases of mental illness has increased disproportionately.”63

The outdated conditions and practices at the Saint Justus asylum were increasingly seen as a stain on Trieste’s aspirations to modernity.64 Over time, administrators and officials in the region began to engage more seriously with psychiatric reform through expert assessments and official reports. In 1877, the Lieutenant of Trieste, Felix Pino Freiherr von Friedenthal, condemned the state of the asylum, noting its failure to meet contemporary medical or ethical standards. He acknowledged that scientific treatment was often impossible and that confinement in such an institution could even worsen a patient’s condition. The asylum was no longer seen as a place of healing, but as a source of harm that contributed to the chronic nature of mental illness:

The only asylum for the Littoral region in Trieste is too small to accommodate all those in need of medical care, which, if administered at the onset of illness and in a timely manner, could restore reason to many of these unfortunate individuals. As a result, there are frequent refusals to admit these people, who, either left to fend for themselves or rendered harmless to themselves and others by methods that are sometimes inhumane, often slip into an incurable state of chronicity. Furthermore, the facility in Trieste […] no longer meets the advancements of modern science.65

Concerns about the inhumane treatment of patients, including harsh confinement and even acts of violence committed by the nursing staff, were already evident in the new guidelines for the Trieste psychiatric hospital, which were discussed and approved by the city council in 1873: “[Nurses, A. N.] must not use coercive means without prior authorization from the doctors. In urgent cases, if it becomes necessary to apply this measure, they shall do so collectively, as the patient, merely by the presence of multiple nurses, ceases all violence or reprisals.”66

Thanks to close collaboration with scientific experts, the political authorities in the Littoral developed a growing knowledge of psychiatric advances across the Habsburg Empire and beyond. This fostered a more refined understanding of mental illness, better diagnostic tools, and new treatment possibilities. A crucial shift came with the official recognition of the distinction between “curable” and “incurable” mental illnesses, which redefined illness and shaped the cultural and social acceptability (and unacceptability) of individuals with mental or neurological conditions.67 This distinction influenced how health systems were organized, prompting the separation of patient categories to enable more appropriate care. As one Lieutenancy’s report of 1862 stated, “the incurable maniacs must be separated from the curable, and to achieve this, either two separate establishments must be built or a single institution must be divided entirely into two distinct sections, one dedicated to the admission and care of the incurable and the other for the detention and psychiatric treatment of the curable.”68

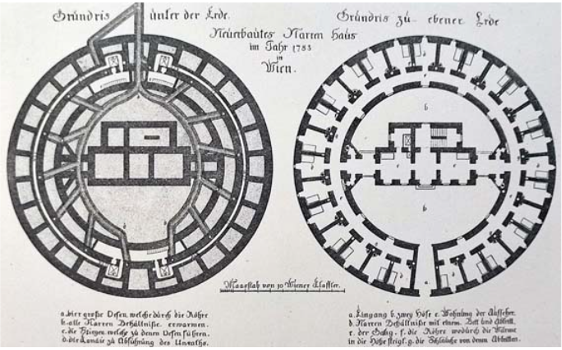

From the 1880s onwards, doctors and other professionals from the Littoral’s bourgeois professions, including engineers and architects, produced numerous pamphlets addressing the region’s psychiatric crisis and aimed at informing policymakers and civil society.69 These echoed earlier critiques of the outdated and inhumane conditions at Trieste’s Saint Justus asylum.70 Most of these assessments reiterated the core ideas of Dr. Pontoni’s essays: respectful patient care, the separation of curable and chronic cases, modern diagnostics, and psychiatry as a means of treatment and reintegration rather than control. Central to their proposals was the Anglo-German “open-door system,” with (preferably asymmetrical) pavilion layouts and agricultural colonies for occupational therapy. Both the bourgeoisie and the psychiatric community of Trieste were also inspired by the Geel model of family-based care for incurable patients,71 which gained new prominence across Europe and North America in the late nineteenth century.72

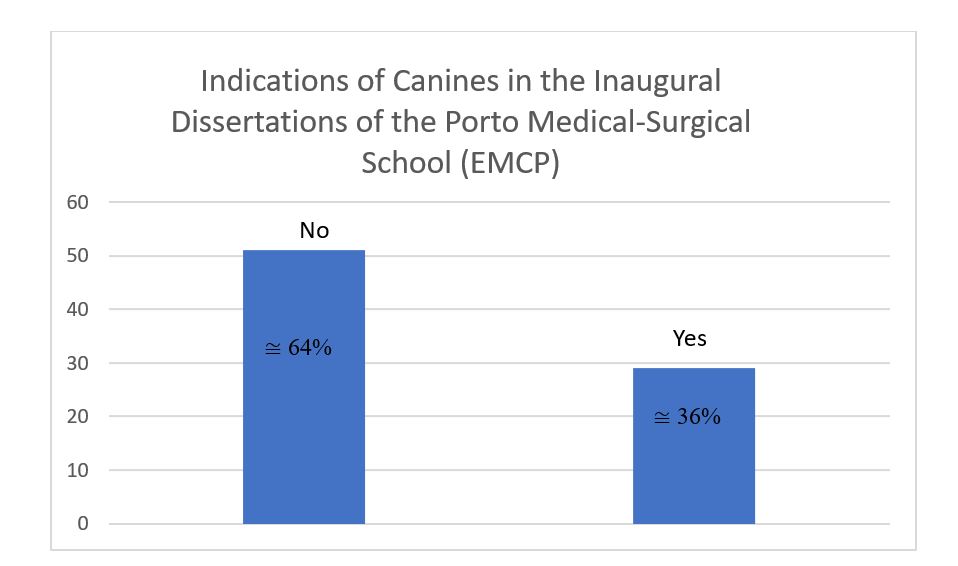

Trieste’s psychiatric reforms followed Central and Northern European models, and expert commissions traveled across the continent to study asylum practices. The concept of “modernity” in psychiatric science became the dominant framework, overriding political and nationalist ideologies. In the late nineteenth century, Trieste, like other Littoral provinces, saw rising nationalist tensions with the increasing prominence of parliamentary politics, as Italian, Slovene, and Croatian parties gained influence locally and imperially.73 The National-Liberal Party, which represented much of Trieste’s Italian-speaking elites, aligned with an idealized vision of “Italian-ness” and a pro-Italy irredentist political stance, and it gained control of the Trieste municipality for decades starting from the 1860s onwards.74 However, in 1896, a traveling commission was organized by the irredentist city council to study the most modern models of psychiatric hospitals and therapies across Europe. In its final report, the commission openly criticized Italian psychiatry as conservative and outdated.75 Hopes for reform in Italy had largely faded in the face of the conservative, organicist, and criminalizing approach to mental illness adopted by the majority of the Italian psychiatric community. This culminated in Law no. 36 of 1904, which effectively undermined non-restraint care.76 Italian institutions failed to reflect the modern ideals sought by the elites of Trieste, who instead turned to British and German-Austrian non-restraint systems as models of progress. In liberal, bourgeois Trieste, many of the cherished ideals (if not the ideology) of modernism often proved more influential than the irredentist nationalism embodied by the municipal administration.77 In fields like medicine and psychiatry, these ideals enabled more flexible and negotiable expressions of national and ideological identity.78

“Above all, the asylum must be entirely removed from the appearance of a prison or convent. It must therefore create a pleasant impression for both the in-patient and the visitor, helping to lift the spirits of those who must rely on such an institution.”79 These maxims by the Triest engineer Natale Tommasi from 1893 stemmed from the sociopolitical principles of late nineteenth-century bourgeois liberal society. The creation of facilities that, in line with modernist and scientific theories, embodied a prototype of “caged liberty” was intended to address the issue of respecting patients’ individual rights and challenging entrenched sociocultural prejudices and the stigma surrounding mental illness.80 However, it was far removed from the deinstitutionalizing reforms and anti-psychiatric theories of the later twentieth century,81 as well as from efforts to question the hierarchical, paternalistic doctor–patient relationship. The mentally ill still had to be controlled and governed from above, but also cared for and, where possible, cured, with the ultimate goal of reintegrating as many patients as possible into society.82

After extensive discussions, planning, and study trips, the Littoral was ultimately endowed with two of the most modern asylums in the Habsburg Monarchy. The original plan for a single central asylum for the entire crownland was abandoned in favor of a division.83 The new municipal asylum in Trieste, located in the semi-rural district of Saint John, began operating in 1908.84 Named after the Triest businessman and benefactor Andrea di Sergio Galatti, its construction reflected the hybrid public-private model of welfare/philanthropy promoted by the cosmopolitan upper- and middle-class elites and their active role in shaping a more “liberal” asylum model.85 In 1911, the smaller provincial asylum in Gorizia was opened in the rural suburb San Pietro/Šempeter, named after Emperor Franz Joseph I.86 As with other asylum projects in the Monarchy (such as the projects in Mauer-Öhling, Salzburg, Steinhof close to Vienna, Prague, and Kroměříž), planners identified the psychiatric hospital in Alt-Scherbitz, Saxony as the most advanced model of “non-restraint” or “open-door” care.87 This choice reflected both the wider anti-psychiatric movement that emerged in the empire in the 1890s and the unique socio-political context of society in Trieste, which was increasingly divided between political liberalism and nationalism, particularly among Italian and Slovenian movements.88 Consequently, both institutions adopted asymmetrical pavilion layouts, and the Gorizia asylum also incorporated an agricultural colony. These psychiatric hospitals on the Adriatic coast emerged as models of modern psychiatric theory and practice, founded on principles of non-restraint, work therapy, outpatient care, and family-based treatment.89 This is evidenced by numerous custody transfers to relatives or legal guardians, as recorded in patient files preserved in the asylums’ archives.90 At their inauguration, they were staffed by a new generation of psychiatrists trained at imperial universities, particularly Vienna, Graz, Innsbruck, and Prague. These practitioners promoted reform psychiatry grounded in modern scientific methods. Efforts were also made to reflect the region’s linguistic diversity. A notable example was the appointment of Fran Göstl, an Austro-Slovenian psychiatrist trained at the Wagner-Jauregg school in Vienna and a strong advocate of non-restraint and family therapy (particularly for patients suffering from alcohol addiction), as chief physician of the new hospital.91

Liberalism, Economy, and Psychiatry: Non-Restraint Praxis in a Free Port City

Most historical research on psychiatry has focused primarily on documents from major asylums. However, within the Habsburg Monarchy, asylums constituted only one part of a broader and more complex psychiatric system. Psychiatrists, including those employed in public hospitals, often maintained private practices for affluent, paying patients.92 In addition, other public health institutions such as clinics and hospital wards were gradually established over the course of the nineteenth century. Medical records from asylum archives, such as those of the Sergio Galatti Hospital in Trieste and the Franz Joseph I Hospital in Gorizia, show that most of the patients were hospitalized only after multiple admissions and brief periods of observation in a specialized psychiatric observation ward within the local civic hospitals.

In the port city of Trieste, a special ward for psychiatric and neurological patients was added to the main civil hospital in 1872, expanded in 1884, and formally designated as the “eighth ward” in 1886.93 This development addressed the growing need to manage psychiatric cases amid rapid population growth driven by the city’s economic expansion and industrialization. The ward functioned as a kind of first-aid station, offering prompt reception, observation, and short-term treatment for psychiatric and neurological patients, following the model of the British “after-care” system.94 It also functioned as a triage point, where “chronic” and “non-curable” patients were identified and then transferred to the main asylum, while most patients, diagnosed as “curable” and expected to be treated shortly, were either discharged or entrusted to family care. As a result, most psychiatric patients in Trieste and the wider Littoral region were hospitalized for a maximum of six to eight weeks, with only one-third requiring longer stays and eventual transfer to the asylum.95 The ward was substantial, with an 81-bed observation room and an outpatient service for “nervous and mental diseases,” staffed by a head physician, a doctor, an assistant, and 38 nurses. In the early 1920s, it admitted an average of 650 patients annually, which was slightly above the European average, as Trieste’s hospital also served as a regional hub for areas including Friuli, Istria, Gorizia, Dalmatia, and, in many cases, southern Carniola.96

The Austrian imperial psychiatric system adopted a gradual and hybrid approach to the admission and treatment of psychiatric and neurological cases. This approach was based first on the ministerial ordinance of May 14, 1874, no. 7197 and later formalized by the imperial ordinance of June 28, 1916, no. 207,98 which aimed to regulate the legal procedures for the incapacitation of mental patients better.99 Between society and the closed asylum, there existed a hybrid area formed by observation wards in major civil hospitals across the Monarchy. Admission to these wards was simplified, requiring only a medical certificate. This accessible form of hospitalization was justified on both scientific and ethical grounds. Early intervention aimed to prevent the worsening of conditions, while avoiding full asylum confinement helped reduce the social stigma for both patients and their families. Unlike main asylums, which were obliged to report patients to the police within 24 to 48 hours as mentally ill and potentially dangerous, hospital observation wards and psychiatric clinics were given up to eight days before they were required to notify the authorities.100 This provision made it possible for patients to receive medical and psychiatric care without being formally labeled asylum inmates, offering treatment in a less stigmatizing environment.

This form of daily rehabilitation and observation ward, which embodied the ideas promoted by German psychiatrist Adolf Dannemann regarding non-restraint therapies in psychiatric clinics, became a distinctive feature of the German and Habsburg psychiatric systems.101 It was commonly found in many city hospitals throughout the Monarchy. 102 The Ministerial Ordinance of 1874 no. 71 granted local authorities, whether regional, provincial, or municipal, significant autonomy when it came to the organization of psychiatric facilities. As a result, the ward, which came to be regarded as a center of excellence in Habsburg Trieste, was created and operated as a blend of both imperial and local initiatives in response to the specific needs of the city and the surrounding region. The ward was shaped by the same liberal political and social ideology that was driving the development of modern, non-restraint asylums.

A quantitative analysis of medical records from the eighth ward of Trieste’s civic hospital reveals a well-structured outpatient practice, marked by the daily administration of pharmacological treatments (mostly sedatives) and short-term therapies tailored to individual patients. In some cases, patients were admitted multiple times over the course of months or years, and treatment continued beyond discharge through outpatient or family-based care, following the signing of an official certificate by relatives or guardians who assumed legal responsibility for the patient. The records also show that both patients and their families exercised a degree of agency within the institution. Most admissions were voluntary, initiated by the patient or his or her relatives on the basis of a medical certificate, except in cases of compulsory admission ordered by civil or police authorities due to violent behavior which purportedly posed a threat to public safety. Some cases even illustrate how family members could legally contest decisions made by physicians or the district judge responsible for public safety and request the patient’s discharge if they were willing to accept full legal responsibility.103

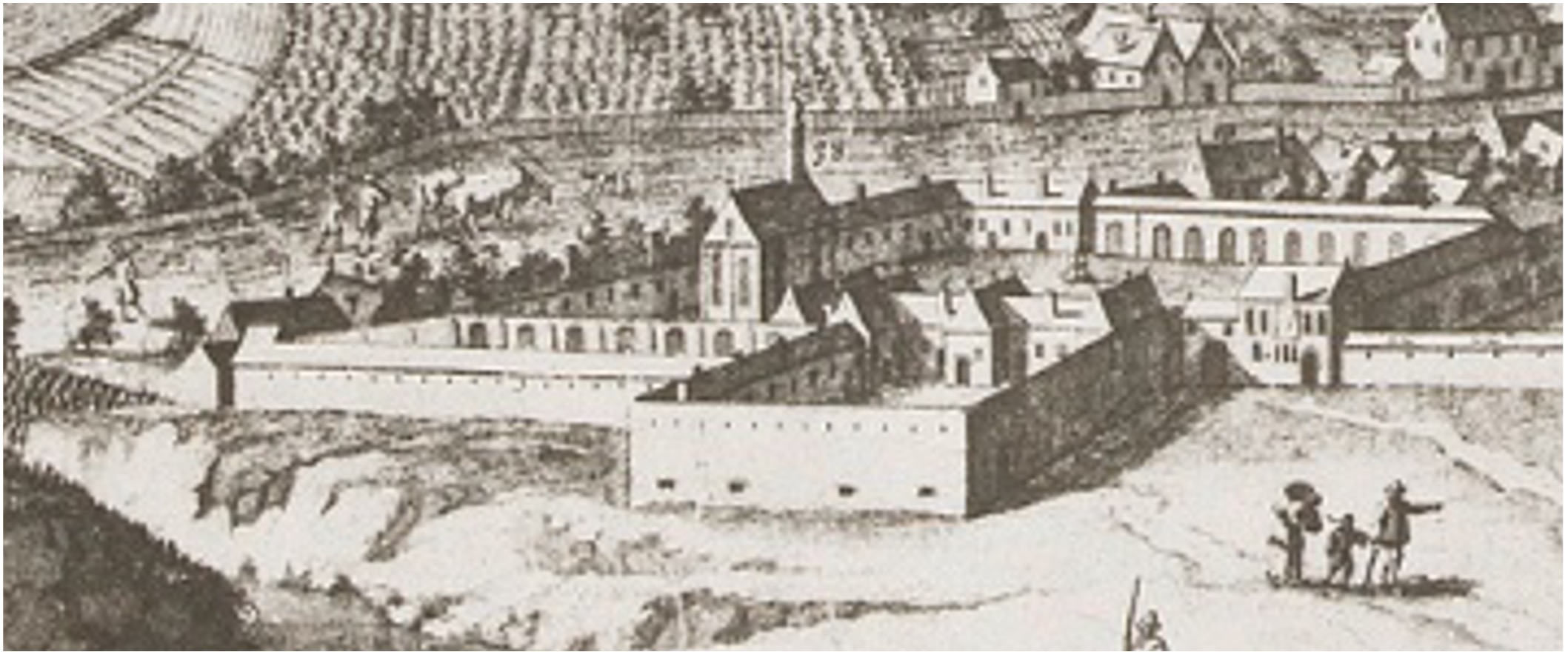

Beyond humanitarian concerns and scientific progress, the self-proclaimed modern city of Trieste required a more responsive system of mental health care. The goal was to address the endemic problems stemming from the rapid growth of its free port and industry, as well as the largely unmanaged urban influx of poor and needy workers of diverse national backgrounds drawn by the expanding job market. This model of outpatient and short-stay psychiatric care was located in the city center, in contrast to the new asylum situated on the outskirts (see Fig. 1).104 Its central location allowed for swift admissions, short stays, and early forms of family-based care. The institution reflected Trieste’s urban, demographic, and economic transformation. It was located in a district of the “new city,” developed alongside the old town in the second half of the nineteenth century and inhabited largely by the working-class population employed in the port and urban industries. When the ward was established in the early 1870s, Trieste was experiencing renewed economic growth and a deep structural shift from a commercial center and free port to an industrial port city, following a temporary stagnation crisis after 1855.105 The city’s population surged from around 105,000 in 1857 to approximately 226,000 by 1910,106 driven by mass migration from surrounding provinces, such as Istria, Gorizia-Gradisca, and Carniola, as well as from Central and Eastern Europe, the Italian and Balkan peninsulas, and the wider Mediterranean basin.107 This rapid and largely unregulated expansion created acute social pressures, as urban infrastructure lagged behind. Large sections of the city became densely populated, and working-class residents lived under severely deteriorated conditions.108

From a liberal bourgeois and capitalist perspective, the presence of a psychiatric outpatient department for short stays in the main civic hospital functioned as a form of soft control for a working-class society. It provided a less invasive and more immediate form of care and shelter for workers who, rather than being rendered inactive and confined to an asylum on the fringes of the socioeconomic fabric, were needed for the functioning of Trieste’s port and industrial system. Thus, scientific, sociopolitical, humanitarian, and economic dimensions converged in psychiatric practice, with the simultaneous aims of control, assistance, treatment, the preservation of social respectability, and the rapid reintegration of patients into the labor market. In a liberal bourgeois city such as Trieste,109 entirely devoted to commercial and economic development and guided by the principle of the “primacy of economy,” such a system was fundamental to the operation of its social and production structures.110 In this sense, the eighth ward of the Trieste hospital served as a vital mechanism with which to maintain the city’s social and production systems.111 It functioned more as a rehabilitation institute, particularly for patients not diagnosed as chronic and seen as intellectually able enough to be an active part of working society.112

Figure 1. Map of the city of Trieste (extract), circa 1920: the larger circle marks the location of Andrea di Sergio Galatti,

the new provincial psychiatric hospital, situated in the peripheral district of Saint John; the smaller circle indicates the Civic Hospital of Trieste,

where the eighth psychiatric division was located in the heart of the new part of town

(BCTs: Port of Trieste, Scale 1:10,000, ca. 1920)

Postwar Transition and Fascism: A Clash between Psychiatric Cultures

After decades of internal difficulties and stagnation in the late nineteenth century, the modernization of the two asylums and the evolving psychiatric system on the Adriatic coast stood out, together with examples such as Vienna’s Steinhof. This progress was particularly striking when compared to the neighboring Italian peninsula, with the contrast most evident between the Austrian Littoral and the Italian province of Friuli. Udine’s new asylum, inaugurated in 1904 (the year in which the Italian asylum law was passed), was hailed as the most advanced example of Italian psychiatry.113 Under its future director, Giuseppe Antonini, it was conceived as an open-door, wall-free facility with a pavilion layout and an agricultural colony, although its rigidly symmetrical design conflicted with the Alt-Scherbitz non-restraint model, which favored asymmetry to minimize any suggestion that patients were under some form of control.114 While the Littoral’s lack of a modern asylum briefly fueled irredentist claims portraying Italian Friuli as more progressive,115 these faded as Udine’s asylum soon encountered resistance from provincial authorities and drifted from its founding ideals, adopting containment practices in line with national legislation. Disillusioned, Antonini acknowledged Italy’s psychiatric backwardness in a 1909 publication following his visit to Steinhof.116 More significantly, the opening of the Littoral asylums deepened the divide between the Austrian and Italian psychiatric systems. Reformist hopes among Italian psychiatrists, who were often inspired by German models, were ultimately thwarted by internal opposition, the restrictive framework of the Italian 1904 law, and the outbreak of World War I.117

The psychiatric system of the Austrian Littoral was deeply disrupted by World War I and its aftermath. The Upper Adriatic became a war zone along the Isonzo Front, and this had a severe impact on psychiatric care. In Gorizia, once a model of Habsburg psychiatry, the hospital was repeatedly caught in the crossfire after Italy declared war on Austria-Hungary in May 1915. By the end of that year, patients and staff had been evacuated to the main mental hospital in Kroměříž, and the facilities were almost completely destroyed.118 While Trieste’s mental hospital remained physically intact, it faced serious setbacks, including severe shortages of materials, funds, and personnel. Many physicians were conscripted into the Austro-Hungarian army. There was also a sharp rise in the demands placed on the facilities at the hospital due to its proximity to the front. After the war, psychiatry in Trieste came under even greater strain with the mass influx of returning refugees, prisoners, and soldiers passing through the port city.

Furthermore, the end of the war and the conquest of the former Littoral by the Italian army in November 1918 dealt an additional blow to local psychiatric institutions. The greatest shock came from the abrupt and violent shift from being part of a multicultural empire to inclusion in a nation state which, shortly after the war, became one of Europe’s earliest totalitarian regimes, as the fascist dictatorship rose to power in October 1922. In the former Littoral, now part of the so-called Italian “new provinces,” this transition was even more abrupt than in the rest of Italy. As early as 1920, this newly annexed multilingual border region bore witness to a particularly harsh rise of fascist squads, culminating in the violent persecution of non-Italian-speaking populations and increasing pressure for forced nationalization. These nationalistic sentiments sparked the brutal assault and burning down of the Narodni Dom building, which had been the cultural, political, and economic center of the Slovenian bourgeoisie in the heart of the city. The attack took place in July 1920. It was carried out by Fascist squads which acted with the approval of the Italian army and police.119

From the perspective of the science of psychiatry, this transition also represented a profound rupture within an already devastating context, triggering a clash between distinct medical and psychiatric cultures. The introduction of Italian psychiatric practice, characterized by a rigid adherence to an organicist conception of mental illness as codified by the 1904 law,120 led to a marked divergence in the “new provinces,” such as the former Austrian Littoral and South Tyrol.121 In the mid-1920s, fascist local authorities, in line with the broader agenda of the fascist regime, initiated a general reform of the public health system, focusing on restructuring civil hospitals and asylums, particularly in Trieste. Between 1923 and 1925, the public health system and especially psychiatric care in Trieste came under direct attack and reform by the new fascist administration. Under the guise of cost-cutting and system rationalization, plans were made to dismantle the city hospital’s eight wards for psychiatric and neurological patients and to replace them with a similar, though fundamentally different, service located within the main asylum.122 The primary target of this reform was the hospital’s flexible system of hospitalization and outpatient care, which did not require the formal denunciation of the patient to the public security forces. In the Italian system, such outpatient and observation wards were virtually non-existent. Furthermore, under Italian law, the procedure for admitting an “alienated person” involved greater oversight than under Austrian law, as it required the involvement of municipal, provincial, and medical authorities, along with supervision by the public security forces. Moreover, since the Italian law was rooted in a more strongly criminalizing approach to psychiatric illness than in Habsburg Trieste, it required the immediate denunciation of individuals upon admission to an asylum.123 As a result, asylums in Italy functioned more as juridical than medical institutions.124

A heated confrontation between the former Habsburg medical class in Trieste and the new Italian hospital administration and authorities erupted between 1923 and 1925. The medical elite in Trieste, rooted in the prestigious and internationally recognized “Viennese Medical School”125 and shaped by the Habsburg medical and psychiatric tradition, still belonged to a defeated and collapsed empire. After November 1918, it found itself at odds with a victorious nation state and a rising authoritarian regime, which sought to assert control through the reorganization of medicine and psychiatry. The conflict was not merely a professional reaction to a perceived violation of independence and identity, nor was it simply a dispute between differing medical and psychiatric traditions. It was also a deeper clash between two opposing political and social visions: on one side, a liberal (albeit paternalistic and class-based) conception of care and rights; on the other, an illiberal and totalitarian project intent on limiting civic and political freedoms. Though this topic has not yet been adequately studied, there is consensus in the secondary literature on the fascist regime’s political use of psychiatric institutions to control, discipline, and silence not only anti-fascist opponents but also anyone deemed incompatible with its vision of the new social order. Fascism took advantage of the repressive, police-oriented nature of the 1904 psychiatric law, which was incorporated into the authoritarian legal framework of the leggi fascistissime (the so-called “very fascist laws”) and codified by the “Unified Text of Public Security Laws” in 1925–1926, precisely the very same years in which the psychiatric ward in Trieste was closed. Psychiatry thus became part of the fascist state’s control apparatuses for enforcing “public security”126 and pursuing its broader eugenic ambition to reshape Italian society (and the Italian “race”).127

A new regulation for the Trieste public health system was finally issued in 1927, replacing the Austrian legislation. The new text, which was intended to align with the regulations and practices of Italian psychiatry, reflected the law’s core conception, centered on the absolute notion of the mentally ill person’s dangerousness as “a threat to himself and others” and a source of “public scandal.” The forced custody and hospitalization of the patient were prescribed, directly undermining the non-restraint practice. Consequently, in 1925, the eighth ward of the main civil hospital in Trieste was closed. Since the services it had provided were essential for urban society and well-integrated into the public health system, they could not be easily discontinued. As a result, a smaller version of the ward was established in a pavilion at the Sergio Galatti psychiatric hospital, but it still lost its original hybrid character. This change followed the general trend in fascist public health policies, which aimed to create a new kind of outpatient dispensary system for people who suffered from mental illnesses.128

This change also affected family custody and care practices. While outpatient and family therapy had also been in place in the Italian Kingdom since the late nineteenth century, these services were significantly reduced during World War I and further curtailed under the Fascist regime, which cut provisions for families caring for mentally or neurologically ill relatives.129 Although patients could still be entrusted to family care, the principle of non-restraint and patient release was altered after the closure of the eighth ward. A patient was now only released from the main asylum after he or she had been registered with the police as a potential public threat, and the release was done on an “experimental basis,” meaning the patient was still subject to ongoing checks by police and sanitation personnel every four months. Furthermore, the admission process became more complex, involving the physician, the mayor, the police, and the provincial court, which had to approve the final admission.130 As a result, patients no longer enjoyed the protections once offered by the Austrian imperial ordinance and the eighth division of the civil hospital in Trieste against public denunciation and social stigma.

Facing these shocking shifts, beneath their repeated proclamations of loyalty to the new nationality and state, local psychiatrists and authorities began to develop a “culture of defeat.”131 This culture became embedded in the collective “long memory” of the local medical and civil society over the course of the interwar period and the immediate postwar period, continuing into the 1960s and 1970s.132 Following the collapse of his faith in the promises of modernism and progress in the sciences, the former chief physician of the eighth ward, Eugenio Gusina, expressed his bitter disappointment with the changing situation and launched a vivid and emotional attack against the forced process of the “Italianisation” of the psychiatry system in the former Littoral. He went so far as to make the incisive pronouncement that I have borrowed in the title of this article: “we cannot see ourselves reflected in all Italian institutions.”133

Conclusion: Tracing a Genealogy of “Tradition” through Psychiatry Reform

Opposition to coercive psychiatric practices and the promotion of anti-restraint reforms became central to discourses of “tradition” and “heritage” in the identity-making processes of post-Habsburg societies. The aim of the analysis here has not been to evaluate the truthfulness of such discourses in an essentialist sense, but rather to reconstruct a genealogy of identity narratives that were continually reshaped, transmitted, and revived in moments of profound crisis over the course of the twentieth century.

The case study of the Upper Adriatic, positioned on the margins of the former Habsburg Empire, is not intended merely as a local history. Instead, it is a contribution to a broader interpretative framework relevant to the history of psychiatry and the study of post-imperial transitions in Central Europe. From a long-term perspective, it highlights psychiatry as a field where continuities and ruptures in political order, cultural practices, and professional identities were repeatedly negotiated.

Two moments proved particularly significant in this process. The first followed the empire’s dissolution, during the “Italianization” of the Upper Adriatic and the rise of fascism in the region and the Italian state in the 1920s. The second emerged in the 1960s–1970s, amid economic crisis, geopolitical détente, and the rise of deinstitutionalizing psychiatric reforms. In both phases, psychiatry served as a strong marker of self-identification for a local society in the former Habsburg Central European space. Yet this was not a matter of superficial “nostalgia” for a lost world. Rather, it was a complex response to a profound contemporary “dilemma” that confronted actors with paradigm shifts of cultural and political order, as well as with personal and professional crises.134 “Habsburg traditions” were not immutable legacies but constructs that required constant reinterpretation and adaptation to contemporary needs. The turn to an imagined imperial past and efforts to reintegrate into Austrian and Central European psychiatric networks thus represented more than a superficial “Habsburg fantasy.”135 They were part of an ongoing exercise in identity construction, grounded in the rediscovery of reformist traditions disrupted by both World Wars and interwar authoritarianism.

By the 1960s and 1970s, familiar motifs of late nineteenth-century “modernism” (mobility, multilingualism, and liberal humanism) were reactivated as resources for professional, cultural, and even political self-definition. The psychiatric reform movement initiated in Gorizia and culminating in Trieste became both a local and a transnational reference point, enabling the reconfiguration of a historically fragmented space within the Alpe Adria region. Although historically uneven, the ideological contrast between Habsburg humanism and Fascist authoritarianism proved an enduring and influential rhetorical topos. It legitimized both local and transnational identities centered on non-coercive care, and it positioned the region as historically innovative and responsive to global transformations. At its core lay a post-Habsburg self-identification shaped by the empire’s distinctive interplay between local and imperial loyalties, which fostered enduring habitus and mentalities resilient to twentieth-century upheavals.136 The construction of a genealogy of reformist psychiatric tradition ultimately served the needs of the present, for to create a “tradition” is to shape and plan a future by recalling the past.137

In this sense, the Upper Adriatic experience provides a direct answer to the question posed at the outset: the field of psychiatry (and its critics) did indeed contribute to shaping forms of collective, professional, and cultural self-identification. Far from occupying a marginal position, psychiatric reform became a privileged lens through which broader cultural and geopolitical reconfigurations were articulated, and within the post-Habsburg world, it emerged as a key site for understanding identity-making in post-imperial and borderland contexts.

Archival Sources

Archivio Basaglia [Basaglia Archive, Venice] (AB)

Correspondences (1953–1974)

Archivio Provinciale di Gorizia [Provincial Archive of Gorizia] (APGo)

ARPGo: Archivio della Rappresentanza Provinciale di Gorizia 1861–1923 [Archive of the Provincial Government of Gorizia]

OPP: Ospedale psichiatrico provinciale [Provincial Psychiatric Hospital]

Archivio di Stato di Trieste [State Archive of Trieste] (ASTs)

IRLL: Imperial-Regia Luogotenenza per il Litorale [Imperial and Royal Lieutenancy for the Littoral]

RG VG: Regio Governatorato per la venezia Giulia [Royal Governorate for the Julian March]

RP VG: Regia Prefettura per la Venezia Giulia [Royal Prefecture for the Julian March]

OPP: Ospedale psichiatrico provinciale [Provincial Psychiatric Hospital]

OCTs: Ospedale Civico di Trieste [Civic Hospital of Trieste]

Biblioteca Civica di Trieste [City Library of Trieste] (BCTs)

Istruzione interna per il civico manicomio di Trieste, approvata dalla Delegazione municipale nella seduta 2 aprile 1873 (BCTs, R.P. 1199, N. 23223)

Lorenzutti, Ettore. Progetto del nuovo manicomio. Rapporto illustrativo (BCTS, R.P. misc. 4/3926)

Bibliography

Primary Sources

207. Kaiserliche Verordnung vom 28. Juni 1916 über die Entmündigung (Entmündigungsordnung), Reichsgesetzblatt 43 (1916): 481–92.

71. Verordnung des Ministeriums des Innern im Einvernehmen mit dem Justizministerium vom 14. Mai 1874, mit welcher Bestimmungen in Betreff des Irrenwesens erlassen werden, Reichsgesetzblatt 24 (1874): 179–84.

Antonini, Giuseppe. “Il grande nuovo manicomio di Vienna in Steinhof.” Note e riviste di psichiatria, diario del San Benedetto. Manicomio provinciale di Pesaro 2, no. 2 (1909): 40–49.

Camera dei medici di Trieste. Memoriale diretto all’inclito consiglio della città in oggetto della deficienza di spazio nel civico ospedale e della riorganizzazione del personale medico addetto allo stabilimento. Trieste: Tipografia Augusto Levi, 1895.

Canestrini, Luigi. “Frenocomio civico ‘Andrea di Sergio Galatti’ in Triest.” In Die Irrenpflege in Österreich in Wort und Bild, edited by Heinrich Schlöss, 132–39. Halle: Carl Marhold, 1912.

Dahl, Richard. Der Bankrott der Psychiatrie. Vienna–Leipzig: Robert Coen, 1905.

Fratnich, Ernst. “Landes-Irrenanstalt Franz Josef I. in Görz (Küstenland).” In Die Irrenpflege in Österreich in Wort und Bild, edited by Heinrich Schlöss, 108–31. Halle: Carl Marhold, 1912.

Göstl, Fran. “V Gorici za svetovne vojne.” Življenje in svet, September 5, 1938, 150–51.

Gusina, Eugenio. “Parere del dott. Eugenio Gusina primario dell’VIII divisione sulla progettata soppressione dell’VIII divisione psichiatrica.” In Relazioni, pareri e proposte sulle riforme da introdursi nell’esercizio dell’Ospedale civico a scopo di economie, 55–72. Trieste: Caprin, 1923.

Hermann, Rudolf. Entmündigungsordnung. Kaiserliche Verordnung vom 28. Juni 1916, Reichsgesetzblatt Nr. 207, über die Entmündigung. Vienna: Manz, 1916.

Hofmokl, Eugen. Heilanstalten in Österreich: Darstellung der baulichen, spitalshygienischen und ärztlich-administrativen Einrichtungen in den Krankenhäusern Entbindungsanstalten und Irren-Anstalten ausserhalb Wiens. Vienna and Leipzig: Alfred Hölder, 1913.

Juch, Giuseppe. Il manicomio di Udine: reminiscenze e confronti: un cittadino goriziano ai suoi concittadini. Gorizia: Tipografia Giuseppe Juch, 1905.

L’ospedale psichiatrico provinciale di Gorizia. Gorizia: Tipografia sociale, 1933.

L’ospedale psichiatrico provinciale di Udine nei suoi primi cinquant’anni di vita 1904–1954. Udine: Arti grafiche friulane, 1954.

Lugaro, Ernesto. I problemi odierni della psichiatria. Milan: R. Sandron, 1906.

Mazorana, L. Il nuovo manicomio di Trieste. Trieste: Tipografia della Società dei Tipografi, 1899.

Pontoni, Luigi. Considerazioni del Dr. Luigi Pontoni circa le tre proposte della giunta provinciale di Gorizia sulla questione del manicomio. Gorizia: Seitz, 1900.

Pontoni, Luigi. La questione di manicomio in crisi acuta. Gorizia: Seitz, 1901.

Pontoni, Luigi. Un progetto di grande riforma sul nostro campo sanitario. Gorizia: Tipografia Ilariana, 1914.

Progetto di un nuovo manicomio per la città di Trieste. Trieste: Tipografia della Società dei Tipografi, 1897.

Relazioni, pareri e proposte sulle riforme da introdursi nell’esercizio dell’Ospedale civico a scopo di economie. Trieste: Caprin, 1923.

Schlöss, Heinrich. Die Irrenpflege in Österreich in Wort und Bild. Halle: Carl Marhold, 1912.

Starlinger, Joseph. “Kaiser-Franz-Josef-Landes-Heil- und Pflegeanstalt Mauer-Oehling, Nieder-Oesterreich.” In Die Irrenpflege in Österreich in Wort und Bild, edited by Heinrich Schlöss, 217–26. Halle: Carl Marhold, 1912.

Tamburini, Augusto, Giulio Cesare Ferrari, and Giuseppe Antonini. L’assistenza degli alienati in Italia e nelle varie nazioni. Turin: Unione Tipografico-Editrice torinese, 1918.

Tommasi, Natale. Relazione e descrizione tecnica concernente il progetto per la erezione di un manicomio interprovinciale in Trieste. Trieste: Tipografia Pastori, 1893.

Veronese, Francesco. La questione del manicomio per le tre provincie di Trieste, Istria e Gorizia. Venice: Tipografia dell’emporio, 1889.

Secondary Literature

Ableidinger, Clemens. “Psychiatrie als Diskurs- und Politikfeld: Entstehung und Entwicklung des Politikfelds mental health unter Franz Joseph I.” Ph.D. diss., University of Vienna, 2023.

Ableidinger, Clemens. “Whose Experts? How Federalism Shaped Psychiatry in the Late Habsburg Monarchy.” History of Psychiatry 35, no. 2 (2024): 158–76.

Adcock, Robert, Mark Bevir and Shannon C. Stimson. “A History of Political Science: How? What? Why?” In Modern Political Science Anglo-American Exchanges since 1880, edited by Robert Adcock, Mark Bevir, and Shannon C. Stimson, 1–17. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2007.

Agnelli, Arduino. La genesi dell’idea di Mitteleuropa. Milan: Giuffrè, 1971.

Andreozzi, Daniele and Loredana Panariti. “L’economia di una regione nata dalla politica.” In Il Friuli-Venezia Giulia. Storia d’Italia, vol. 2 of Le regioni dall’Unità a oggi, edited by Roberto Finzi, Claudio Magris, and Giovanni Miccoli, 807–89. Turin: Einaudi, 2002.

Andreozzi, Daniele. “L’organizzazione degli interessi a Trieste (1719–1914).” In La città dei traffici (1719–1918): Storia economica e sociale di Trieste, vol. 2, edited by Roberto Finzi, Giovanni Panjek, and Loredana Panariti, 191–231. Trieste: Lint, 2003.

Ara, Angelo. “The ‘Cultural Soul’ and the ‘Merchant Soul’: Trieste between Italian and Austrian Identity.” In The Habsburg Legacy: National Identity in Historical Perspective, edited by Ritchie Robertson and Edward Timms, 58–66. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1994.

Ara, Angelo and Claudio Magris. Trieste: Un’identità di frontiera. Turin: Einaudi, 1982.

Babini, Valeria. Liberi tutti: Manicomi e psichiatri in Italia: una storia del Novecento. Bologna: Il Mulino, 2009.

Badano, Valentina. “The Basaglia Law. Returning Dignity to Psychiatric Patients: The Historical, Political and Social Factors that Led to the Closure of Psychiatric Hospitals in Italy in 1978.” History of Psychiatry 35, no. 2 (2024): 226–33. doi 10.1177/0957154X231224650

Ballinger, Pamela. “Imperial Nostalgia: Mythologizing Habsburg Trieste.” Journal of Modern Italian Studies 8, no. 1 (2003): 84–101. doi 10.1080/1354571022000036263

Baratieri, Daniela. “‘Wrapped in Passionless Impartiality?’ Italian Psychiatry during the Fascist Regime.” In Totalitarian Dictatorship: New Histories, edited by Mark Edele and Giuseppe Finaldi, 138–56. New York–London: Routledge, 2014.

Blackshaw, Gemma and Sabine Wieber, eds. Journeys into Madness: Mapping Mental Illness in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. New York: Berghahn, 2012.

Blasich, Giorgio et al. Organizational Models for Primary Care in Alps-Adria. Health Protection for the Elderly: Health Prevention of Non-Selfsufficiency: A Proposal for an Analysis Methodology. Alpes-Adria Working Community, Commission IV Health and Social Affairs, Project Group Organizational Models for Primary Care, 1997.

Bösl, Elsbeth, Anne Klein and Anne Waldschmidt, eds. Disability History. Konstruktionen von Behinderung in der Geschichte: Eine Einführung. Bielefeld: Transcript, 2010.

Breschi, Marco, Aleksej Kalc and Elisabetta Navarra. “Storia minima della popolazione di Trieste (secc. XVIII–XIX).” In La città dei gruppi (1719–1918): Storia economica e sociale di Trieste, vol. 1, edited by Roberto Finzi and Giovanni Panjek, 69–238. Trieste: Lint, 2001.

Brink, Cornelia. Grenzen der Anstalt: Psychiatrie und Gesellschaft in Deutschland 1860–1980. Göttingen: Wallstein, 2010.

Bucarelli, Massimo. “The Adriatic Section of the Iron Curtain: Italy, Yugoslavia, and the Question of Trieste during the Cold War.” In Breaking down Bipolarity: Yugoslavia’s Foreign Relations during the Cold War, edited by Martin Previšić, 171–89. Berlin–Boston: De Gruyter Oldenbourg, 2021. doi: 10.1515/9783110658972-011

Burns, Tom, and John Foot, eds. Basaglia’s International Legacy: from Asylum to Community. Oxford–New York: Oxford University Press, 2020.

Caltana, Diego. “Psychiatrische Krankenanstalten in der Provinz der Monarchie: Görz und Triest.” Psychopraxis 11, no. 5 (2008): 10–18. doi: 10.1007/s00739-008-0068-5

Cassata, Francesco. Building the New Man: Eugenics, Racial Science and Genetics in Twentieth-Century Italy. Budapest–New York: CEU Press, 2011.

Catalan, Tullia. “Trieste: ritratto politico e sociale di una città borghese.” In Friuli e Venezia Giulia: Storia del ‘900, 13–32. Gorizia: LEG, 1997.

Cattaruzza, Marina. “Die Migration nach Triest von der Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts bis zum Ersten Weltkrieg.” In Die Moderne und ihre Krisen: Studien von Marina Cattaruzza zur europäischen Geschichte des 19. und 20. Jahrhunderts. Festgabe zu ihrem 60. Geburtstag, edited by Sacha Zala, 83–114. Göttingen: V&R Unipress, 2012.

Cattaruzza, Marina. “Il primato dell’economia: l’egemonia politica del ceto mercantile (1814–1860).” In Il Friuli-Venezia Giulia, vol. 1 of Storia d’Italia: Le regioni dall’Unità a oggi, editied by Roberto Finzi, Claudio Magris, and Giovanni Miccoli, 149–79. Turin: Einaudi, 2002.

Cattaruzza, Marina. Italy and Its Eastern Border, 1866–2016. London–New York: Routledge, 2017.

Cattaruzza, Marina. La formazione del proletariato urbano: Immigrati, operai di mestiere, donne a Trieste dalla metà del secolo XIX alla Prima guerra mondiale. Turin: Musolini, 1979.

Cattaruzza, Marina. “Nationalitätenkonflikt in Triest im Rahmen der Nationalitätenfrage in der Habsburgermonarchie 1850–1918.” In Deutschland und Europa in der Neuzeit, edited by Ralph Melville, Clauss Scharf, Martin Vogt, and Ulrich Wengenroth, 709–26. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner, 1988.

Cohen, Gary B. “Our Laws, Our Taxes, and Our Administration: Citizenship in Imperial Austria.” In Shatterzone of Empires: Coexistence and Violence in the German, Habsburg, Russian and Ottoman Borderlands, edited by Omer Bartov and Eric Weitz, 103–21. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013.

Colaianni, Luigi. Il no-restraint nella psichiatria italiana: Storia di una scomparsa. Fasano: Schena, 1992.

Corbellini, Gilberto and Giovanni Jervis. La razionalità negata: Psichiatria e antipsichiatria in Italia. Turin: Bollati Boringhieri, 2008.

Corsa, Rita. Edoardo Weiss a Trieste con Freud: alle origini della psicoanalisi italiana: le vicende di Nathan, Bartol e Veneziani. Rome: Alpes, 2013.

Crossley, Nick. Contesting Psychiatry: Social Movements in Mental Health. London–New York: Routledge, 2006.

Degrassi, Michele. “L’ultima delle regioni a statuto speciale.” In Il Friuli-Venezia Giulia. Storia d’Italia: Le regioni dall’Unità a oggi, vol. 1, edited by Roberto Finzi, Claudio Magris, and Giovanni Miccoli, 759–804. Turin: Einaudi, 2002.

De Peri, Francesco. “Il medico e il folle: istituzione psichiatrica, sapere scientifico e pensiero medico fra Otto e Novecento.” In Malattia e medicina. Storia d’Italia, vol. 7, edited by Franco della Peruta, 1060–140. Turin: Einaudi, 1984.

De Rosa, Diana. “Dal Conservatorio dei poveri al manicomio di San Giovanni. 1773–1970.” In L’ospedale psichiatrico di San Giovanni a Trieste: storia e cambiamento 1908–2008, 26–47. Trieste: Electa, 2008.

Di Fant, Annalisa, ed. Dalla beneficenza al welfare: dall’Istituto generale dei poveri di Trieste all’Azienda pubblica di Servizi alla Persona ITIS (1818–2009). Trieste: La mongolfiera Libri, 2009.

Dietrich-Daum, Elisabeth, Hermann J. W. Kuprian, Siglinde Clementi, Maria Heidegger, and Michaela Ralser, eds. Psychiatrische Landschaften: Die Psychiatrie und ihre Patientinnen und Patienten im historischen Raum Tirol seit 1830. Innsbruck: Innsbruck University Press, 2011.

Finzen, Asmus. Kurze Geschichte der psychiatrischen Tagesklinik. Bonn: Edition Das Narrenschiff im Psychiatrie-Verlag, 2003.

Finzen, Asmus. Stigma psychische Krankheit: Zum Umgang mit Vorurteilen, Schuldzuweisungen und Diskriminierungen. Cologne: Psychiatrie-Verlag, 2013.

Foot, John. The Man Who Closed the Asylums: Franco Basaglia and the Revolution in Mental Health Care. London: Verso, 2015.

Fragiacomo, Paolo. Italia matrigna: Trieste di fronte alla chiusura del cantiere navale San Marco (1965–1975). Milano: Franco Angeli, 2019.

Fussinger, Catherine. “‘Therapeutic Community’, Psychiatry’s Reformers and Antipsychiatrists: Reconsidering Changes in the Field of Psychiatry after World War II.” History of Psychiatry 22, no. 2 (2011): 146–63. doi: 10.1177/0957154X11399201

Gijswijt-Hofstra, Marijke, Harry Oosterhuis and Joost Vijselaar, eds. Psychiatric Cultures Compared: Psychiatry and Mental Health Care in the Twentieth Century: Comparisons and Approaches. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2005.

Glassie, Henrie. “Tradition.” In Eight Words for the Study of Expressive Culture, edited by Burt Feintuch, 176–97. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2003.