What Factors Are Conducive to Coherence?

Translation Activity in Late Medieval Western Europe:

A Sketch of a Research Program

Péter Bara

HUN-REN Research Center for the Humanities, Institute of History

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it., This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Hungarian Historical Review Volume 14 Issue 2 (2025): 158-185 DOI 10.38145/2025.2.158

Why is the history of intellectual change in the Middle Ages a history of selectively studied influences about which so few historians have dared venture generalizations? Why is it so rich with contradictions? And why do we have so little comprehensive knowledge about the translators behind these intellectual changes? To answer these questions, this article proposes a novel approach to the history of Greek-Latin translations between 1050 and 1350, which substantially reshaped the Medieval Latin intellectual landscape and the cultural history of Europe. After reviewing the conclusions in the most recent secondary literature, the essay offers a sketch of a historical analysis of translation-centered decision-making processes. In doing so, it singles out four hypotheses and describes four research areas corresponding to these assumptions. The proposed research examines the translators’ personalities and activities, their training, mobility, cultural patronage, networks and their audiences (including universities) that influenced their decisions when they chose to translate texts from Greek into Latin. Such an analysis will help us better understand the expanding cultural networks between the medieval Western and Eastern Mediterranean and the development of translations in Latin-using Western Europe.

Keywords: medieval translations, translations from Greek into Latin, medieval knowledge transfer, Byzantine influence on the medieval West 1100–1300

This Special Issue fills a scholarly gap, probably the most significant in historical translation studies. The endeavors and influences of single translators or groups of translators have already been studied for their historical, social, and literary contexts in greater numbers.1 In contrast, there are relatively few overarching studies that further an understanding of “translation movements” and the coherence and social backdrop behind the works, methods, and results of subsequent generations of translators and epoch-long translation activities.2 The essays in this issue take steps towards establishing an explanatory framework and seek to identify factors conducive to translating texts between a wide range of source and target languages. This paper collects a preliminary set of criteria according to which the coherence behind translations in a specific period can be assessed. My expertise allows me to bring evidence concerning late medieval (eleventh-century to fourteenth-century) translations from Greek into Latin in Western Europe. The features described in the following pages lay the basis for the rest of the issue and offer ideas for future research.

Factors Conducive to Translations from Greek into Latin, 1050–1350:

State-of-the-Art

Translation activity from Greek (and Arabic) into Latin between 1050 and 1350 substantially reshaped the Medieval Latin intellectual landscape and brought about a dramatic shift in the cultural history of Europe. For example, Johannes, a scholar in late eleventh-century Northern Italy, put together a list of the medical books he possessed.3 His books contained 26 newly edited texts composed or translated in the previous century. Johannes witnessed a revolution in medical learning and book culture that had recently taken place. A look at the list of medical bestsellers in the long eleventh century reveals that, of the 18 titles, ten were translations from Arabic and Greek. How could this happen? By the mid-fourteenth century, the entire corpus of Galen’s works and some of Hippocrates’ writings had been translated into Latin. The landscape of medical learning and knowledge was not the only place where these kinds of changes were underway, however. According to my preliminary investigations on translated texts from Greek into Latin, 30 identifiable translators produced 208 texts between ca. 1050 and 1350. The working list of translations includes the Medieval Latin corpus Aristotelicum, a few texts by Plato, mathematical texts (in particular Euclid and Archimedes), Proklos, Dionysian texts, medical texts (especially Galen and Hippocrates), texts on geography, astronomy, miscellanea (horse medicine, falconry), patristic theology and religion, a few lives of philosophers, and astrology and esoteric texts.4

Although the origins of the Greek-Latin translations have long been of interest to historians of the period, an important point of departure is the observation that the last systematic attempt to explore how and why the translations came into being was made just over a century ago. Charles Homer Haskins and other modern scholars have seen the medieval translators’ achievements in a larger European context, which was labelled the “twelfth-century Renaissance.”5 They argued for the existence of a Western European renewal between ca. 1050 and 1200, which also had a lasting impact in the later centuries of the Middle Ages. Researchers noted that a significant body of translations from Arabic and Greek was produced, and these texts were salient features of developments in Western Europe. They referred to this as a “translation movement.” Haskins’ research focused on the long twelfth century, so the timeframe of his ideas concerning this “translation movement” covers this period. The task remains to approach subsequent translations from the perspective of a more analytical term that includes several “movements,” such as the term “translation phenomenon.”6

At present, scholarly explanations of a systematic “translation movement” can still be traced back to Haskins’ ideas. Haskins’ pioneering work laid the foundations of medieval translation studies and provided the first survey of Greek-Latin and Arabic-Latin translators and translations. However, the state-of-the-art of his day (especially the large number of unpublished sources) did not allow him to provide a standard, overarching analytical account of translations. Nonetheless, he developed partial hypotheses which, sometimes implicitly, influenced his views. The first hypothesis is that multicultural environments, such as trilingual (Arabic-Greek-Latin) Southern Italy in the eleventh century, provided the motivations and interactions necessary to produce translations.7 Michael Angold recently pointed out that this assumption needs modification.8 In multicultural environments, written multilingualism ran parallel to and followed the respective (Greek, Latin, Arabic) traditions of law and administration, as Julia Becker has shown.9 Latin translations were needed when information was channeled to Latin-using elites who did not know Greek (or Arabic). The second hypothesis, which is present in Haskins’ oeuvre10 and in many works since then,11 is to link knowledge of Greek in the Middle Ages to the eastward movement of people from Western regions where Latin was used. In other words, Medieval Latin scholars must have travelled “to the East” to learn the language(s) and acquire manuscripts. A third assumption is that school reform and the birth of universities played a role in the production and spread of translations. While these assumptions arguably call attention to certain aspects conducive to the development of a “Greek-Latin translation movement,” they do not offer a coherent explanation of this “movement.”

Since Haskins’ pioneering monographs in 1924 and 1927, the vast field of Greek-Latin translations has been researched in several ways. Scholars have studied the lives of translators and the bodies of translations they produced.12 This secondary literature is often useful as a body of work on specific individuals and texts, especially because it substantially updates Haskins’ oeuvre. Yet it is marked by systematic blind spots. It gives little consideration, for instance, to the broader historical context in which these translations were produced or the audiences for the new texts. More importantly, it does not go beyond Haskins’ abovementioned analytical assumptions, which at present beg reconsideration. This is particularly the case since researchers have in the meantime produced a significant number of critical editions (such as the Aristoteles Latinus13 and the Archimedes collection)14 that add considerably to the body of available sources, not only compared to Haskins’ day but also since d’Alverny and Berschin produced their surveys. The increasing number of critical texts makes it possible to draw a much more detailed picture than either Haskins or Berschin was able to do. The increasing quantity of available data at hand enabled scholars to offer synopses that focused on a region or center where translations were produced.15 Finally, scholars discussed the reception history of a single text16 or a coherent group of texts.17 Despite considerable research in the field, there is still no comprehensive explanatory framework that addresses the historical causes, processes, and effects of translations and translators. This issue sets out to address this challenge.

Daniel G. König offered the first overarching explanatory framework of Arabic-Latin translations.18 His study involved locations in Europe and the broader Mediterranean where translations were produced and read between the eleventh and the sixteenth centuries. König singled out the following explanatory building blocks. First, geopolitical shifts, such as the Western encroachment on al-Andalus, Sicily, and the Eastern Mediterranean, influenced the emergence and/or availability of specific forms of bilingualism (König labeled it “intellectualized,” a term which I will discuss below) and the beginnings of translation activity. Second, after the “translation movement” started, its scope and duration were determined by the availability and thematic breadth of appropriate texts, the motivations to translate, and the supporting institutions of patronage. Third, the translated texts became institutionalized as part of the curriculum in monastic and cathedral schools and nascent universities. Fourth, the medieval translation movement reached its end and left its legacy. Haskins’ assumptions and König’s explanatory scheme offer a point of departure for formulating four hypotheses and defining the areas of study that help us approach late medieval Greek-Latin translations.

Factors Conducive to Translations from Greek into Latin, 1050–1350: A Tentative Explanatory Framework

Against the backdrop of previous scholarship, I will present in detail the following four hypotheses:

1. Study of translators’ “intellectual bilingualism” and mobility uncovers how the period’s emerging mobility infrastructure (trade routes, travel opportunities) was connected to the rapidly developing scholarly infrastructure (namely, schools, universities, and different courts).

2. Study of the strategies and means used by translators to characterize their roles (or what I will refer to as self-representation) reveals the ways in which their work overlapped and intersected with contemporary scholarly, political, and economic discourses. It also sheds light on the ways in which the decisions they made helped them establish themselves as cultural mediators and knowledge innovators.

3. Study of translators’ networks and writings demonstrates that a division of labor existed between men of learning and patrons, who were ultimately responsible for masterminding external knowledge import.

4. Dissemination of this imported knowledge took place on different levels and according to a complex set of factors that cannot be reduced to a simpler level of analysis. Analyses of translators’ multi-level knowledge import (including lists, texts, canons, and knowledge organization patterns) uncover mechanisms which remain unknown behind the medieval educational and intellectual shift after ca. 1150–1300 (i.e., the birth of universities and their influence on intellectual history).

Intellectual Bilingualism and Mobility

To understand the motivations of the historical actors who drove the growth of translation activity and the motivations behind the translations themselves, it is necessary to revisit König’s concept of “intellectualized bilingualism.” This means exploring translators’ mobility, through which they acquired their bilingual skills. The roles translators played as cultural mediators can be fruitfully studied by identifying two overlapping infrastructures, without which medieval Greek-Latin translators could not have become cultural agents on the move. These are the A) mobility infrastructure, which provided Greek-Latin translators access to B) scholarly infrastructure. Mobility had a linking function between Western educational centers (schools and libraries) and those of the multicultural zones, such as Southern Italy and Byzantine centers, especially Constantinople. The rediscovery of classical and Byzantine Greek heritage could not have occurred without Westerners exploiting manuscript holdings and Greek education in these zones. The correlation of the two infrastructures can be examined through concrete steps: 1) Collecting available data regarding Greek-Latin translators’ movement based on their biographies and works. 2) Examining the sending contexts of translators: where did the translators come from, what functions did they have in these places, and what was the purpose of travel? 3) Analyzing the receiving contexts: where did the translators go, and what functions did they have in these places? 4) Investigating the infrastructures translators used during their mobility (e.g. diplomats or tradesmen) and its relation to their work as translators. 5) Examining the specific cases of translators in the broader context of Western schools and Byzantine Greek education, with a focus on the possible influence on translations of factors such as different levels of education, curriculum, methods, and necessary time to attain specific skills and expertise. 6) Analyzing how Westerners became insiders in Greek educated society.

My approach, which is based on the notion that one must study translators’ mobility (their travels) and their education side by side, draws on previous scholarship which has called attention to the prerequisites for translating scholarly writings. By establishing the term “intellectualized bilingualism,” König created a novel analytical approach.19 His work provides a key to the study of translations in relation to multiculturality, as Haskins stressed. König emphasized that the translation of specific, in this case scholarly-scientific texts required not only appropriate language skill in oral communication in the source and target languages. In the case of Greek-Latin translations, it also required mastery of the language of Greek source texts, namely a classicizing artificial Greek language20 and patristic Greek, which could be learned from Byzantine masters in schools alongside the concomitant details (termini technici and cultural contexts) of disciplines such as philosophy, theology, or mathematics. In addition, the translator needed Latin schooling in language and the respective disciplines.

Scholars since Haskins rightly point to a breakthrough in the eleventh-century and twelfth-century Western Latin school system and a new, increased interest in manuscript heritage. Schools in their social milieus between 1080 and 1215 are surveyed by Cédric Giraud21 and universities in the volume edited by Hilde De Ridder-Symoens.22 Jacques Verger discussed all stages in the schooling of men of learning between the thirteenth and fifteenth centuries.23 Examples from regional contexts are given by Cédric Giraud, Constant Mews,24 Robert Witt,25 Stephen Ferruolo,26 Carl Mounteer,27 and Joachim Ehlers.28 With regards to Byzantine education (eleventh–fourteenth centuries), it was assessed in general by Paul Lemerle,29 Sita Steckel,30 and Costas Constantinides.31 Paul Magdalino32 and Niels Gaul33 described eleventh-century and early fourteenth-century Byzantine education as a social phenomenon. So, there are tools at hand to assess which types of schools Greek-Latin translators might have attended and the kinds of knowledge they could have mastered during the period in question, even if there is not much evidence concerning where, when, or if they actually attended schools, apart from the content of their translations and work (method, vocabulary, etc.), which gives an indication of their training.

I also set out from the hypothesis based on Haskins’ work that mobility was indeed a crucial feature of the translation movement. The availability of schools alone would have been insufficient unless translators had acquired language skills and specialized knowledge in both systems (the Latin and Byzantine). As König emphasized in his model, through geopolitical shifts, the period in question witnessed an expanding Western network in the Western and Eastern Mediterranean basin through trade, pilgrimage, territorial gains, and the crusading movement. The question is how Greek-Latin translations used these networks. As part of the expanding Western networks, cultural and linguistic contact zones became triggers behind the translation of texts. Future research must offer a comprehensive analysis of how Greek-Latin translators, (after) being educated in Latin language and scholarly culture, entered these contact zones, learned Greek, and became familiar with elements of classical Greek history and culture that enabled them to undertake the translation of scholarly texts.

Understanding translators’ mobility means examining the mobility of specific groups and general movement patterns. Previous scholarship has established some aspects of this migration and mobility, and it provides a useful methodological tool for further studies. My preliminary investigations proved that Haskins’ abovementioned hypothesis was right: between 1050 and 1350, 28 of the 30 best-documented translators pursued their activities by moving between centers (from England, France, and Italy to Greece, Constantinople, and Antioch).34 As part of Migrationsforschung in a Western-Byzantine relation, Krijnie Ciggaar examined Western travel to Byzantium.35 The presence of Western merchants,36 soldiers,37 and diplomats38 in Byzantium was also the subject of research. Most recently, Leonie Exarchos investigated the services performed by Western intellectuals in the Byzantine court.39 The Viennese project “Mobility, Microstructures, and Personal Agency” presented Byzantine society and culture at the crossroads of Eastern and Western influence.40 In these works, translators are members of specific groups, such as diplomats, intellectuals in Byzantine service, etc.

The approach I propose is to focus explicitly on individual translators and comparisons of their lives and works with the lives and works of their contemporary colleagues in translation. Whereas I accept many of the premises of the abovementioned contributions, I consider it more beneficial to analyze the characteristics and development of each individual topic (education in Latin and Greek and the mobility of translators) rather than moving too rapidly to a higher level of generalization.

Translators’ Self-Representation

To understand how translators carved out agency for themselves, I find it fruitful to assess Greek-Latin translators’ self-representation by discussing 1) the methods with which translators asserted themselves as figures of authority, 2) the reasons they used to justify translating texts, 3), their relation to their subject matter, namely classical Greek and Byzantine material, 4) their uses of ideas from and contributions to the translation theory tradition, and finally, 5) the ways in which they constructed their identities and roles in relation to political, social, and scholarly patterns of the period. In order to offer the necessary backdrop, the social milieus from which translators arrived must be explored. Hitherto, Greek into Latin translators’ roles as mediators have only been subject to case studies.41 Thus, there is no comprehensive picture of the knowledge transfer process. An obvious remedy to this state-of-the-art is to survey all available case studies with the intention of developing a comprehensive interpretative model of the sociocultural processes that framed Greek-Latin translation work.

Previous scholarship has implied that translators are not just implementers, but autonomous decision-makers and drivers of knowledge accumulation, with historical context-dependent roles and motivations. I plan to investigate these implications in a systematic way and consider what it meant for translators to belong to specific social groups and how they represented their complex and situational social identities.

Such research studies the agency of translators in the cultural and knowledge transfer process. Transfer agents have been investigated as “cultural brokers” in and between courts,42 and their roles in crossing spatial, religious, social, and cultural boundaries have been emphasized.43 The Toletan translator Dominicus Gundissalinus, for instance, introduced the Aristotelian classification of knowledge through Arabic intermediaries, such as al-Farabi.44 Translators’ relations to earlier traditions (e. g. in the case of Burgundio of Pisa45 or concerning Amalfitans)46 and to the achievements of other translators have been assessed.47 Dimitri Gutas collected texts on why translators interpreted specific (in that case, scholarly-scientific) texts.48 José Mártinez-Gázquez examined Arabic translators’ relations to Arabic science, which was their subject matter.49 I argued that some translators may have achieved more than others because of their birth/social status by highlighting that Cerbanus Cerbano could defy the doge of Venice because he (Cerbanus Cerbano) was the offspring of an ancient Venetian noble family.50 Peter Classen demonstrated that Burgundio of Pisa was a noble and leading statesman in Pisa.51

Based on the cases of eleventh-century Constantinopolitan imperial employees, Leonie Exarchos established a partial interpretative framework, calling attention to the authority-making process through language and factual skills and also stays and education in Greek-speaking territories.52 Rita Copeland wrote a tour-de-force model book on the influence of translation theory on medieval translations to vernaculars.53

Translators’ prologues and other paratexts are among the most essential sources for the study of their activities. A fruitful approach would be to survey all surviving prologues (both published and unpublished) from the quills of Greek-Latin translators from the period as a whole. Réka Forrai created an analytical framework.54 She looked at prefaces as conceptual narratives and investigated a small portion of recurrent commonplaces/topoi, namely utility, poverty, and bellic/martial topoi. The framework Forrai proposed can be extended by assembling a comprehensive list of clichés (as was also done with other text groups, such as Byzantine saints’ lives)55 alongside the role of other elements in these texts in relation to commonplaces. Consequently, the commonplaces can be analyzed as a means with which the translators constructed their “selves” to provide their credentials, establish their relations to contemporary science, indicate the novelties they brought to it, and show their relations to translation theory. Finally, the statements made by translators could be set against other contemporary narratives, be they private or public (the use of non-Christian knowledge in education and public discourse),56 political57 (e.g., the translatio studii et imperii),58 or social (for instance, utilitas),59 to show how translators construct self-representation in a social or political dimension. The investigation of topoi in the prefaces is closely linked to the systematic study of the social background of Greek-Latin translators on the basis of available sources. Accordingly, textual analysis is combined with historical research to further a nuanced understanding of the social positions of the translators and their networks.

Networks and Patrons

I also seek to understand the social factors that helped or hampered the successful circulation of translations. In order to achieve this goal, one must 1) construct a prosopography-centred dissemination history of translations and 2) analyze the roles of patrons. How can one make sense of the bewildering variety of circumstances under which translations were produced? I will explore what made up for the gaps and inconsistencies that characterized specific translators’ translating activities, bridged subsequent generations of translators, or, alternatively, fostered systematic results and the coherence of translators’ work in other cases. I seek explanations by exploring the socio-cultural contexts of translators who belonged to a network of scholars and patrons and who, even unconsciously, practiced a division of labor that ultimately was responsible for producing an array of texts that suited their needs. I depart from the assumptions that 1) a scholarly community consisting of translators, scholars, and patrons was responsible for the coherence behind translations and the systematic results and, 2) their activities and efforts to make new texts accessible to a Western audience were influenced by filtering factors of textual transmission.

The first topic to be discussed is the question of the scholarly community, namely of a new social group which, as Jacques Le Goff and Jacques Verger have shown,60 came into being in the eleventh century and continued to place increasingly prominent roles in intellectual exchange: the medieval men of learning. I plan to explore this group as audience and initiators of translations and analyze the specificities of this community to understand better the conditions that shaped the production of translations. A crucial question to answer is how masters in cathedral schools and, after c. 1200, the university elite, including teachers and top-tier students, became the primary audience of translated texts.61 In this knowledge-production procedure, patrons played a crucial role. So far, patrons have been studied only on a case-by-case basis,62 and there is no coherent account of translators’ patrons that includes the impact of the shifting educational paradigm (monastic learning-cathedral school-university) and assesses the roles of different (princely, royal, papal) courts.

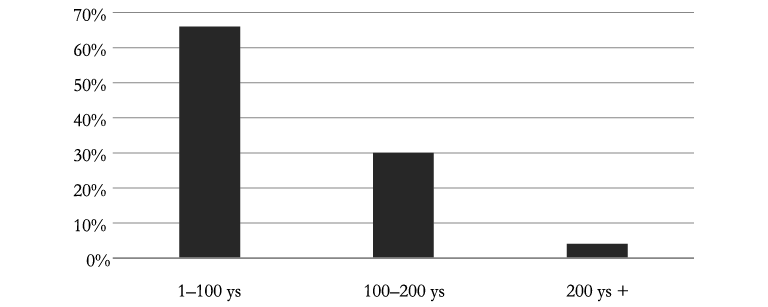

Table 1. Ratio of available MSS following production

I seek to assess the specific roles of translators in this socio-cultural context. Réka Forrai (the “utility-narrative” in the translations’ prefaces)63 and Charles Burnett64 demonstrated that the translators consciously enriched the Latinate community with their work, i.e. learning languages and producing Latin texts for the benefit of other intellectuals. Except for a very few cases, such as John Sarrazin65 or Peter of Abano,66 translators from Greek were not teachers. According to the medieval notion of translation, a proper translation replaced the original text, which then became unnecessary.67 So, Charles Burnett emphasized that teaching masters rarely learned languages.68 Instead, they were content to rely entirely on the Latin translations.

One major task is to forge a prosopography-centered dissemination history of published translated texts, studying the process as it unfolded until new materials become available and accessible to the interested public. This involves tracing the translators’ networks, i.e., translators’ personal connections from their perspective, and exploring the knowledge hubs/ learned networks that played crucial roles in the reception of the translated texts. The study of translators’ networks inevitably involves exploring textual dissemination patterns. Concerning textual dissemination, micro and macro levels can be identified. The micro-level refers to the milieu of the translator and first addressee(s) of the translated material involving the actual production circumstances. The macro-level refers to the spread of the translated text to a broader scholarly community and to knowledge hubs such as courts, schools, and universities. This might happen, e.g. through a ruler’s letter,69 monastic networks,70 or university copy houses (the stationarii in the pecia-system).71 From a methodological point of view, micro- and macro-level dissemination can be analysed using different source materials. The actual production circumstances might be found in the prologues to the translations and in documents related to the translators’ biographies. The macro level can be assessed only by studying the history of specific texts in great detail, which involves considerably more data than the study of the micro level.

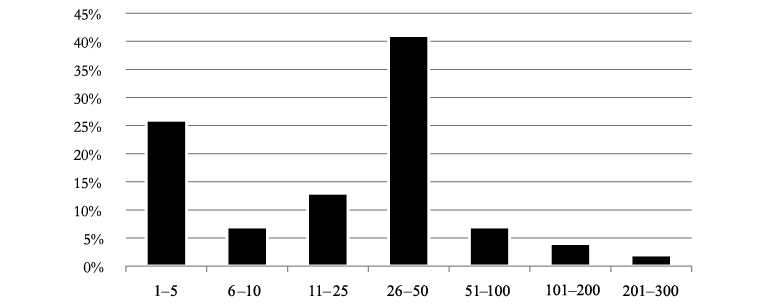

Table 2. Number of surviving MSS of critically published translations

According to my preliminary overview, 49 percent of the textual corpus is critically edited, which is a prerequisite for a feasible and representative dissemination survey. Editors considered 2372 manuscripts to produce their texts, 66 percent of which had been copied within a century after the translators produced their first versions (Chart 1 above). Chart 2 shows that 87 percent of the texts survived in less than 50 witnesses (33 percent less than 10). The arguably high number of manuscripts significantly drops if one deducts the 6 percent of more than 100 witnesses, constituted by such works as Aristoteles’ Posterior Analytics or Metaphysics. More importantly, by drawing manuscript branches, the editors singled out which manuscripts would constitute the target of my research. I will focus on the “root manuscripts” that served as the basis for later copies. In the case of the Posterior Analytics (James of Venice’s eleventh-century translation), this means 10 out of the 289 witnesses.72 Moerbeke’s thirteenth-century translation of the Metaphysics survived in 202 manuscripts, which can be traced back to two Paris University manuscripts (copied in 23 smaller textual units-peciae) and six Italian witnesses.73 Based on the critical editions, manuscript catalogues, and consulting manuscripts, I will consider which people were connected to specific manuscripts and assess their roles in making texts accessible. My aim is to arrive at an understanding on a quantitative-empirical basis of how translated texts surpassed the threshold of the micro-level and reached the macro-level and became more widely accessible by being read, cited, and commented upon. This limitation is based on the scheme that Michael McVaugh established to study Galen’s university reception (see also the next unit).74 McVaugh distinguished between availability (the existence of a translation), accessibility (the specific translation was within the reach of particular groups), and adaptation (the scholarly community studied and interiorized the new text). By setting the limiting criteria of accessibility, my research focuses on the collective decision-making process of introducing new materials instead of assessing the adaptation process, which has been relatively well-researched by historians of the specific fields.

With regards to agency, the micro-level involves the translators and the patron. The patron existed as a commissioner (for instance, the pope in the case of Burgundio of Pisa)75 a financial sponsor (wealthy Amalfitan merchants in Constantinople),76 or simply the individual who gave the idea of translating specific texts (the Aragonese envoy Ramón de Moncada to Leo Tuscus).77 Sometimes, these roles overlapped. The study of patronage involves assessing its changing motivations and goals in secular, religious (ecclesiastical–monastic), and educational contexts: the importance of Benedictine and mendicant patronage (e.g. Monte Cassino’s essential role in manuscript production and housing Constantine the African’s medical project in the late eleventh century,78 or the role played by the Dominican cultural programme in William of Moerbeke’ translations),79 and the shift towards cathedral schools and universities. The roles played by courts in the selection of new texts from Greek is also to be investigated, such as the Papal Curia and Southern Italy under Norman,80 Hohenstaufen (translations from Greek were made especially during the reign of Manfred [r. 1258–1266]),81 and Angevin rulers.

Reaching the Audience: The Degree of Transmission

One important methodological challenge that I will tackle is the varying level of success that translations reached. In some cases (as e. g., I have argued),82 translators produced systematic results. This is particularly true of such cases as Aristotle83 or Galen,84 which were large corpora that successive generations of translators rendered into Latin step by step. Self-standing texts of great importance, such as John Damascene’s Creed/De fide orthodoxa, were also sought and seem to have entered into academic use relatively quickly. Éloi Buytaert has shown that the Creed was translated on the fringes of Latinate Europe (in the Hungarian Kingdom) ca. 1135, but within fifteen years Peter Lombard was already using it in Paris.85 Shortly afterwards, Burgundio of Pisa retranslated the entire work, which Robert Grosseteste reworked in the thirteenth century according to the new academic tastes.86 In contrast, several case studies show that translations were produced under accidental circumstances.87 Moreover, Greek-Latin translators seem to have worked in isolation: they were aware of previous results, but there is little evidence to suggest that they undertook shared projects with their contemporaries.88

To assess dissemination dynamics, I single out filtering factors that impacted the availability and accessibility of texts. These factors complement personal agency but crucially affected textual histories and the degree of transmission. Some texts did not even reach the macro-level or did not circulate widely for reasons that have only been partly identified. Based on case studies of Aristotelian translations, Pieter de Leemans emphasized the importance of external and internal transmission criteria.89

Leemans’ external criteria highlight the circumstances that helped or hampered the procedure through which a text became accessible to its audience. These included accidental events (e. g. some of the model manuscripts were lost in a shipwreck in the case of Constantine the African),90 competing translations from Arabic (see for instance the few people who read Moerbeke’s translation of Ptolemy’s Tetrabiblos from Greek)91 the association of authority with translations (e. g. Thomas Aquinas with Moerbeke’s oeuvre)92 etc. Leemans identifies the correct understanding of the text’s content and message as the internal criterion. I expand this interpretation and seek to understand what roles translators played in successfully transmitting specific contents.

I plan to examine, first, the specific contents transmitted by translators on different levels. This includes studying the lists translators made, which can be considered their first direct contribution to Western scholarship. Henry Aristippus (eleventh century), for instance, translated Aristotle’s life from Greek, which contained a list of the philosopher’s works;93 or Burgundio of Pisa was asked by a Salernitan physician to provide a list of the Galenic works.94 Afterwards, I consider how these lists became new canons in the respective fields. Furthermore, having obtained their intellectualized bilingual skills, translators had access not only to the languages themselves but also to Greek and Arabic systems of thought. Scholars have shown, for instance, that from the eleventh century the late antique Alexandrian medical canon influenced translators’ agendas (in the case of Constantine the African;95 or Burgundio of Pisa).96 Likewise, Alexander Fidora explained97 that the translator and scholar Dominicus Gundissalinus (ca. 1110–1190), in his On the Division of Philosophy, synthesised Latinate tradition (Holy Scripture, Boethius, and Isidore of Seville) with the corpus of Aristotle, which he consulted mainly in Arabic, alongside the explanatory teachings of al-Farabi, Avicenna, and Averroes, among others.98 So, first, I will single out a set of transmission criteria considering the multilevel ways in which translators’ knowledge was imported.

Second, I consider how such developments were connected to a changing educational environment in which the primary venue of scholarly study and discussion shifted from monastic to cathedral schools and universities. My primary focus is on how the newly translated texts found a place in or remained outside of this framework and how they transformed it.

Third, I assess the varying pace of the introduction of new knowledge produced by translators. In doing so, I depart from the premises of previous scholarship,99 which claims that the result of external knowledge import was ubiquitous by the thirteenth century in higher education: Aristotle’s oeuvre superseded the previous medieval curriculum in the nascent universities. In contrast, Michael McVaugh argues that in medicine, novel texts entered curricula only decades after their production because the established terminology only gradually gave way to new terminology.100

In addition, I also analyze the mechanisms of translators’ knowledge import by focusing on the field that was a thirteenth-century innovation and was substantially influenced by translators: university education. For reasons of feasibility, I plan to study knowledge import in medical education, which constituted one of the three higher university faculties. I will examine the availability and reception of Galen’s works translated from Greek. The main questions are the following: 1) How can successive stages of the arrival of the “new Galen” be described from the viewpoint of translations from Greek considering multi-level knowledge import (lists of texts, texts, and coherent corpora, such as curricula)? 2) Which Galenic works became more successful and which remained marginal and why? 3) How did medical knowledge hubs/receiving contexts define this procedure ca. 1100–1350? Galen (129–216 AD) was a key medical authority in the Middle Ages.101 The Galeno Latino project provides a comprehensive dataset of Galen’s oeuvre in Latin, inventorying Greek and Arabic translators and translations, alongside their manuscripts.102 The census of manuscripts has proven that a larger corpus (some 25 works) entered Western curricula by the mid-thirteenth century through Arabic and Latin translations.103 The success of translations from Arabic104 and Greek105 has been sketched, and the first synthesis about their reception at universities has been made.106 I will expand McVaugh’s analytical framework to the period as a whole. In order to solve the problem of diachronic relations between successive translators and their translations, my research employs McVaugh’s availability, accessibility, and adaptation scheme.107 Scholars have shown that it took a relatively long time for new Galenic texts to enter circulation after having been produced. It has also been argued that translations from Arabic played the primary role in establishing medical vocabulary, even though medieval physicians and university teachers acknowledged the linguistic superiority of translations from Greek. The fourteenth-century case of Montpellier has proven that more practical masters did not wish to create a new vocabulary based on Greek models, since it had taken some fifty years for a coherent medical language to have been established, at last, from Arabic.108 While this idea has been accepted,109 the details should be subjected to a systematic survey which analyses additional factors, such as the importance of different academic genres.

Conclusions

The model I propose presents prerequisites and working mechanisms of a knowledge transfer process. This process substantially (re)shaped the institutionalization of learning in Latin-using Europe between the eleventh and fourteenth centuries and gave a decisive impetus to intellectual currents of the period. This model considers the knowledge import process as a series of decisions. By using these ideas as a critical framework and point of departure for research, I propose to further a richer understanding of the work and endeavors of the key figures who played major roles, as translators, in the late medieval Western European intellectual shift. In addition, this research also illustrates how the birth and development of ground-breaking notions and systems of thought came into being as the products of interactions among individuals and groups as well as historical, context-dependent influences.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Analytica posteriora. Translationes Iacobi, Anonymi sive “Ioannis,” Gerardi et Recensio Guillelmi de Moerbeka. 4 vols. Edited by Lorenzo Minio-Paluello, and Bernard G. Dod. Bruges-Paris: Desclée De Brouwer, 1968.

Arabic and Latin Corpus. Edited by Dag Nikolaus Hasse et al. https://www.arabic-latin-corpus.philosophie.uni-wuerzburg.de (last accessed April 4, 2025).

Boethius. In Porphyrii Isagogen commentorum editio secunda. Brepols Library of Latin Texts, on-line edition.

De fide orthodoxa: Versions of Burgundio and Cerbanus. Edited by Éloi M. Buytaert. New York: Franciscan Institute, 1955.

Diogenes Laertius: Lives of Eminent Philosophers. Edited by Tiziano Dorandi. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Ethica Nicomachea. 5 vols. Edited by René A. Gauthier. Leiden–Brussels: Brill-Desclée De Brouwer, 1972–1974.

Metaphysica, lib. I-XIV. Recensio et Translatio Guillelmi de Moerbeka. 2 vols. Edited by Gudrun Vuillemin-Diem. Leiden–New York–Cologne: E. J. Brill, 1995.

Ptolemy’s Tetrabiblos in the Translation of William of Moerbeke: Claudii Ptolemaei Liber Iudicialium. Edited by Gudrun Vuillemin-Diem, and Carlos G. Steel. Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2015.

Secondary Literature

Amerini, Fabrizio, and Gabriele Galluzzo, eds. A Companion to The Latin Medieval Commentaries on Aristotle’s Metaphysics. Leiden: Brill, 2014.

Angold, Michael. “The Norman Sicilian Court as a Centre for the Translation of Classical Texts.” Mediterranean Historical Review 35, no. 2 (2020): 147–67. doi: 10.1080/09518967.2020.1816653

Bara, Péter. “Greek-Latin Translators on the Move, 1050–1200: The Importance of Mobility and its Infrastructures.” Unpublished presentation at the IMC at Leeds, 4 July 2023, see https://www.imc.leeds.ac.uk/imc-2023/programme/ (last accessed April 4, 2025).

Bara, Péter. “Who Was the Author of the Latin Version of Maximos’ Chapters on Charity? Cerbano Cerbani’s Biography from a Comparative Perspective.” In Studies in Maximus the Confessor’s Capita de caritate: Papers Collected on the Occasion of the Budapest Colloquium on Saint Maximus, 3-4 February 2022, edited by Alex Leonas, Vladimir Cvetkovic. Turnhout: Brepols, forthcoming. Preprint at https://www.academia.edu/102752916/Who_was_the_author_of_the_Latin_version_of_Maximos_Chapters_on_Charity_Cerbano_Cerbanis_biography_from_a_comparative_perspective (last accessed Apr 4, 2025).

Bara, Péter, and Paraskevi Toma, eds. Latin Translations of Greek Texts, ca. 1050–1300. Leiden: Brill, 2025.

Bara, Péter. “Greek Thought, Latin Culture. Triggers and Tendencies behind Greek-Latin Translations, ca. 1050–1300: Preliminary Observations.” In Latin Translations of Greek Texts, ca. 1050–1300, edited by Paraskevi Toma and Peter Bara, 22–91. Leiden: Brill, 2025. doi: 10.1163/9789004721678_003

Becker, Julia. “Multilingualism in the Documents of the Norman Rulers in Calabria and Sicily: Successful Acculturation or Cultural Coexistence?” In Multilingual and Multigraphic Documents and Manuscripts of East and West, 33–55, edited by Giuseppe Mandalà, and Inmaculada Pérez Martín. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press, 2018. doi: 10.31826/9781463240004-003

Benson, Robert L., Giles Constable, eds. Renaissance and Renewal in the Twelfth Century. Cambridge (Mass.): Harvard University Press, 1982.

Berschin, Walter. Greek Letters and the Latin Middle Ages: From Jerome to Nicholas of Cusa. Rev. and expanded ed. Washington D. C.: The Catholic Univ. of America Press, 1988.

Berlier, Stéphane. “Niccolò da Reggio traducteur du De usu partium de Galien. Place de la traduction latine dans l’histoire du texte.” Medicina nei secoli 25, no. 3 (2013): 957–77.

Beullens, Pieter. “A Methodological Approach to Anonymously Transmitted Medieval Translations of Philosophical and Scientific Texts: The Case of Bartholomew of Messina.” PhD thesis, Leuven, KU Leuven, 2020.

Beullens, Pieter. The Friar and the Philosopher: Wiliam of Moerbeke and the Rise of Aristotle’s Science in Medieval Europe. Milton: Taylor & Francis Group, 2022.

Beullens, Pieter, and Pieter De Leemans. “Aristote à Paris: Le système de la Pecia et les traductions de Guillaume de Moerbeke.” Recherches de Théologie et Philosophie Médiévales 75, no. 1 (2008): 87–135. doi: 10.2143/RTPM.75.1.2030803

Bossier, Fernand. “Méthode de traduction et problèmes de chronologie.” In Guillaume de Moerbeke: Recueil d’études à l’occasion du 700e anniversaire de sa mort, edited by Jozef Brams et al., 257–94. Leuven: Leuven University Press, 1989.

Brams, Jozef, and Antonio Tombolini, transl. La riscoperta di Aristotele in Occidente. Milano: Jaca Book, 2003.

Burnett, Charles. “King Ptolemy and Alchandreus the Philosopher: The Earliest Texts on the Astrolabe and Arabic Astrology at Fleury, Micy and Chartres.” Annals of Science 55, no. 4 (1998): 329–68.

Burnett, Charles. “Translation and Transmission of Greek and Islamic Science to Latin Christendom.” In The Cambridge History of Science, vol. 2, Medieval Science, edited by David C. Lindberg, and Michael H. Shank, 341–65. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015. doi: 10.1017/CHO9780511974007.016

Burnett, Charles. “The Twelfth-Century Renaissance.” In The Cambridge History of Science, vol. 2, Medieval Science, edited by David C. Lindberg, Michael H. Shank, 365–85. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015. doi: 10.1017/CHO9780511974007.017

Burnett, Charles. “Arabic Magic: The Impetus for Translating Texts and Their Reception.” In The Routledge History of Medieval Magic, edited by Sophie Page, and Catherine Rider, 71–84. New York and Abingdon: Routledge, 2019.

Bydén, Börje, and Filip Radovic, eds. The Parva Naturalia in Greek, Arabic and Latin Aristotelianism: Supplementing the Science of the Soul. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2018.

Campbell, Emma. “The Politics of Medieval European Translation.” In The Routledge Handbook of Translation and Politics, edited by Jonathan Evans, and Fruela Fernandez, 410–23. London: Taylor and Francis, 2018.

Chiesa, Paolo. “Ambiente e tradizioni nella prima redazione latina della Leggenda di Barlaam e Josaphat.” Studi Medievali 24, no. 2 (1983): 521–44.

Cigaar, Krijnie N. “Réfugiés et employés occidentaux au XIe siècle.” Médiévales 12 (1987): 19–24.

Ciggaar, Krijnie N. Western Travellers to Constantinople. The West and Byzantium, 962–1204: Cultural and Political Relations. Leiden: Brill, 1998.

Clagett, Marshall. Archimedes in the Middle Ages. 5 vols. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1964–1984.

Classen, Peter. Burgundio von Pisa: Richter, Gesandter, Übersetzer. Heidelberg: Winter, 1974.

Constantinides, Costas N. Higher Education in Byzantium in the Thirteenth and Early Fourteenth Centuries: (1204–ca. 1310). Nicosia: Cyprus Research Centre, 1982.

Copeland, Rita. Rhetoric, Hermeneutics, and Translation in the Middle Ages: Academic Traditions and Vernacular Texts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

D’Alverny, Marie Thérèse. “Translations and Translators.” In Renaissance and Renewal in the Twelfth Century, edited by Robert Louis Benson, and Giles Constable, 421–63. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1982.

Delle Donne, Fulvio. “Un’ inedita epistola sulla morte di Guglielmo de Luna, maestro presso lo Studium di Napoli, e le traduzioni prodotte alla corte di Manfredi di Svevia.” Recherches de théologie et philosophie médiévales 74 (2007): 225–45.

Dondaine, Antoine. “Hugues Éthérien et Léon Toscan.” Archives d’histoire doctrinale et littéraire du Moyen Âge 19 (1952): 67–134.

Drocourt, Nicolas. Diplomatie sur le Bosphore: les ambassadeurs étrangers dans l’Empire byzantin des années 640 à 1204. 2 vols. Leuven: Peeters, 2014–15.

Durling, Richard J. “Burgundio of Pisa and Medical Humanists of the Twelfth Century.” Studi Classici e Orientali 43 (1995): 95–9.

Ebessen, Sten. “Jacques de Venise.“ In L’Islam médiéval en terres chrétiennes: Science et idéologie. Edited by Max Lejbowitz, et al., 115–132. Villeneuve d’Ascq, 2017. Accessed at https://books.openedition.org/septentrion/13980#ftn13 (last accessed April 4, 2025).

Ehlers, Joachim. “Die hohen Schulen.” In Die Renaissance der Wissenschaften im 12. Jahrhundert. Edited by Peter Weimar. Munich: Artemis, 1981.

Exarchos, Leonie. Lateiner am Kaiserhof in Konstantinopel. Paderborn: Brill Schöningh, 2022.

Federici Vescovini, Graziella. Pietro d’ Abano tra storia e leggenda. Lugano: Agorà, 2020.

Ferruolo, Stephen. The Origins of University: The Schools of Paris and Their Critics, 1100–1215. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1985.

Fidora, Alexander. Die Wissenschaftstheorie des Dominicus Gundissalinus: Voraussetzungen und Konsequenzen des zweiten Anfangs der aristotelischen Philosophie im 12. Jahrhundert. Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 2009.

Fidora, Alexander and Nicola Polloni. “Ordering the Sciences : Al-Farabi and the Latinate Tradition.” Ishraq. Islamic Philosophy Yearbook 10 (2022): 110–30.

Fludernik, Monika and Hans-Joachim Gehrke, eds. Grenzgänger zwischen Kulturen. Würzburg: Ergon, 1999.

Folliet, Georges. “La Spoliatio Aegyptiorum (Exode 3:21–23; 11:2–3; 12:35–36). Les interprétations de cette image chez les pères et autres écrivains ecclésiastiques.” Traditio 57 (2002): 1–48.

Forrai, Réka. “Hostili Praedo Ditetur Lingua Latina: Conceptual Narratives of Translation in the Latin Middle Ages.” Medieval Worlds 12 (2020): 121–39.

Fortuna, Stefania. “II Corpus delle traduzioni di Niccolò da Reggio (fl. 1308–1345).” In La medicina nel basso medioevo. Tradizioni e conflitti, 285–312. Spoleto: Centro Italiano di Studi sul basso medioevo - Accademia Tudertina, 2019.

Fortuna, Stefania, Anna Maria Urso. “Burgundio da Pisa traduttore di Galeno: nuovi contributi e prospettive.” In Sulla tradizione indiretta dei testi medici greci. Atti del II Seminario internazionale di Siena (Certosa di Pontignano, 19-20 settembre 2008). Ed. Ivan Garofalo, 141–77. Rome/Pisa: Fabrizio Serra, 2009.

Gassman, David Louis. “Translatio Studii: A Study of Intellectual History in the Thirteenth-Century.” PhD thesis, Cornell University, 1973.

Gaul, Niels. Thomas Magistros und die spätbyzantische Sophistik: Studien zum Humanismus urbaner Eliten der frühen Palaiologenzeit. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2011.

Giraud, Cédric. “La naissance des intellectuels au XIIe siècle.” Annuaire bulletin de la société de l’histoire de France (2010): 23–37.

Giraud, Cédric. A Companion to Twelfth-Century Schools. Leiden–Boston: Brill, 2020.

Giraud, Cédric, and Constant Mews. “John of Salisbury and the Schools of the 12th Century.” In A Companion to John of Salisbury, edited by Christophe Grellard and Frédérique Lachaud, 29–62. Leiden: Brill, 2015.

Gosman, Martin. “Alexander the Great as the Icon of Perfection in the Epigones of the Roman d’Alexandre (1250–1450): The Utilitas of the Ideal Prince.” In The Medieval French Alexander, edited by Donald Maddox, 175–93. Albany, NY: State Univ. of New York Press, 2002.

Green, Monica. “Medical Books.” In The European Book in the Twelfth Century, edited by Erik Kwakkel, Rodney M. Thomson, 277–93. Cambridge, United Kingdom New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Green, Monica H. “Gloriosissimus Galienus: Galen and Galenic Writings in the Eleventh- and Twelfth-Century Latin West.” In Brill’s Companion to the Reception of Galen, edited by Barbara Zipser, and Petros Bouras-Vallianatos, 319–43. Leiden: Brill, 2019.

Burnett, Charles, Dimitri Gutas, and Uwe Vagelpohl, eds. Why Translate Science?: Documents from Antiquity to the 16th Century in the Historical West (Bactria to the Atlantic). Leiden, Boston: Brill, 2022.

Gutas, Dimitri. “What Was There in Arabic for the Latins to Receive?: Remarks on The Modalities of the Twelfth-Century Translation Movement in Spain.” In Wissen über Grenzen: Arabisches Wissen und lateinisches Mittelalter, edited by Andreas Speer, Andreas, and Lydia Wegener, 3–22. Berlin, New York: De Gruyter, 2006.

Gutas, Dimitri. Greek Thought, Arabic Culture: The Graeco-Arabic Translation Movement in Baghdad and Early ‘Abbasaid Society (2nd-4th/5th–10th c.). London–New York: Routledge, 1998.

Haskins, Charles Homer. Studies in the History of Mediaeval Science. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1924.

Haskins, Charles Homer. The Renaissance of the Twelfth Century. Cambridge: Harvard Univ. Press, 1927.

Hasse, Dag Nikolaus. “The Social Conditions of the Arabic-(Hebrew-)Latin Translation Movements in Medieval Spain and in the Renaissance.” In Wissen über Grenzen: Arabisches Wissen und lateinisches Mittelalter, edited by Andreas Speer, Andreas, Lydia Wegener, 68–86. Berlin, New York: De Gruyter, 2006.

Hasse, Dag Nikolaus. “Der mutmaßliche arabische Einfluss auf die literarische Form der Universitätsliteratur des 13. Jahrhunderts,” In Albertus Magnus und der Ursprung der Universitätsidee, edited by Ludger Honnefelder, 241–58, and 487–91. Berlin: Berlin University Press, 2011.

Hasse, Dag Nikolaus and Ann Giletti, eds. Mastering Nature in the Medieval Arabic and Latin Worlds: Studies in Heritage and Transfer of Arabic Science in Honour of Charles Burnett. Turnhout: Brepols, 2023.

Höfele, Andreas, and Werner Von Koppenfels, eds. Renaissance Go-Betweens: Cultural Exchange in Early Modern Europe. Berlin: de Gruyter, 2005.

Jacob, André. “La traduction de la Liturgie de saint Jean Chrysostome par Léon Toscan: Édition critique,” Orientalia Christiana Periodica 32 (1966): 111–62.

Jacoby, David, ed. Travellers, Merchants and Settlers in the Eastern Mediterranean, 11th–14th Centuries. Farnham: Ashgate Variorum, 2014.

Jacquart, Danielle. “Principales étapes dans la transmission des textes de médecine (XIe–XIVe siècle).” In Rencontres de cultures dans la philosophie médiévale : traductions et traducteurs de l’antiquité tardive au XIVe siècle, edited by Jacqueline Hamesse and Marta Fattori, 251–71. Louvain-la-Neuve: UCL, Institut d’études médiévales, 1990.

Jaspert, Nikolas et al., eds. Cultural Brokers at Mediterranean Courts in the Middle Ages. Munich: Wilhelm Fink, 2013.

Kaska, Katharina. “Zur hochmittelalterlichen Überlieferung von Maximus Confessor, Capita de caritate in der Übersetzung des Cerbanus.” Jahrbuch der österreichischen Byzantinistik 70 (2021): 221–48. doi: 10.1553/joeb70s221

Kischlat, Harald. Studien zur Verbreitung von Übersetzungen arabischer philosophischer Werke in Westeuropa 1150–1400: das Zeugnis der Bibliotheken. Münster: Aschendorff, 2000.

König, Daniel G. “Sociolinguistic Infrastructures: Prerequisites of Translation Movements Involving Latin and Arabic in the Medieval Period.” In Connected Stories: Contacts, Traditions and Transmissions in Premodern Mediterranean Islam, edited by Mohamed Meouak and Cristina de la Puente, 11–75. Berlin, Boston: Brill, 2022.

Kretzmann, Norman et al. The Cambridge History of Later Medieval Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982.

Laiou, Angelike E. and Cécile Morrisson, eds. Byzantium and the Other: Relations and Exchanges. Farnham: Ashgate, 2012.

Le Goff, Jacques. Les intellectuels au Moyen Âge. Paris: Edition du Seuil, 1985.

Leemans, Pieter De. “Aristotle Transmitted: Reflections on the Transmission of Aristotelian Scientific Thought in the Middle Ages.” International Journal of the Classical Tradition 17, no. 3 (2010): 325–53. doi: 10.1007/s12138-010-0200-9

Leemans, Pieter De, ed. Translating at the Court: Bartholomew of Messina and Cultural Life at the Court of Manfred of Sicily. Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2014.

Lemerle, Paul. Byzantine Humanism: The First Phase. Notes and Remarks on Education and Culture in Byzantium from Its Origins to the 10th Century. Translated by Helen Lindsay and Ann Moffatt. Sydney: Brill, 2017.

Lond, Brian. “Arabic-Latin Translations: Transmission and Transformation.” In Brill’s Companion to the Reception of Galen, edited by Barbara Zipser, and Petros Bouras-Vallianatos, 343–59. Leiden: Brill, 2019.

Magdalino, Paul. The Empire of Manuel I Komnenos, 1143–1180. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

Mártinez-Gázquez, José. The Attitude of the Medieval Latin Translators towards the Arabic Sciences. Florence: SISMEL-Galluzzo, 2016.

McVaugh, Michael. “Niccolò Da Reggio’s Translations of Galen and Their Reception in France.” Early Science and Medicine 11, no. 3 (2006): 275–301.

McVaugh, Michael. “Galen in the Medieval Universities, 1200–1400.” In Brill’s Companion to the Reception of Galen. Edited by Barbara Zipser, and Petros Bouras-Vallianatos, 381–93. Leiden: Brill, 2019.

Mounteer, Carl. “English Learning in the Late Twelfth and Early Thirteenth Century.” PhD thesis, University of London, 1973.

Nicol, Donald M. Byzantium and Venice: A Study in Diplomatic and Cultural Relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988.

Nutton, Vivian. “Niccolò in Context.” Medicina nei secoli: Arte e scienza 35, no. 3 (2013): 941–56.

Oldoni, Massimo. “La promozione della scienza: L’ Università di Napoli.” In Intellectual Life at the Court of Frederick II Hohenstaufen, edited by William Tronzo, 251–63. Hanover: University Press of New England, 1994.

Pratsch, Thomas. Der hagiographische Topos: Griechische Heiligenviten in mittelbyzantinischer Zeit. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, 2012.

Rapp, Claudia, and Johannes Preiser-Kapeller, eds. Mobility and Migration in Byzantium: A Sourcebook. Göttingen: V and R Uni Press, 2023.

De Ridder-Symoens, Hilde, ed. A History of the University in Europe. Vol. 1, Universities in the Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

Ronconi, Filippo. “Il Paris. suppl. gr. 388 e Mosè del Brolo da Bergamo.” Italia Medievale e Umanistica 47 (2006): 1–27.

Jonathan, Shepard. Byzantine Diplomacy: Papers from the Twenty-Fourth Spring Symposium of Byzantine Studies, Cambridge, March 1990. Aldershot, Hampshire: Variorum, 1992.

Siraisi, Nancy G. Medieval and Early Renaissance Medicine: An Introduction to Knowledge and Practice. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990.

Steckel, Sita, Niels Gaul, and Michael Grünbart, eds. Networks of Learning: Perspectives on Scholars in Byzantine East and Latin West, c. 1000–1200. Zurich–Münster: LIT, 2014.

Steel, Carlos. “Guillaume de Moerbeke et Saint Thomas.” In Guillaume de Moerbeke. Recueil d’études à l’occasion du 700e anniversaire de sa mort, edited by Jozef Brams et al., 57–82. Leuven: Leuven University Press, 1989.

Rodriguez Suarez, Alex. “The Western Presence in the Byzantine Empire during the Reigns of Alexios I and John II Komnenos (1081–1143).” PhD Thesis, London, King’s College, 2014.

Théry, Gabriel. “Documents concernant Jean Sarrazin.” Archives d’histoire doctrinale et littéraire du Moyen Âge 18 (1951): 45–87.

Urso, Anna Maria. “Translating Galen in the Medieval West: The Greek-Latin Translations.” In Brill’s Companion to the Reception of Galen, edited by Barbara Zipser, and Petros Bouras-Vallianatos, 359–81. Leiden: Brill, 2019.

Urso, Anna Maria. “In Search of Perfect Equivalence. The uerbum de uerbo Method in Burgundio of Pisa’s Translations of Galenic Works.” In Latin Translations of Greek Texts, ca. 1050–1300, edited by Paraskevi Toma, and Peter Bara, 234–62. Leiden: Brill, 2025.

Veit, Raphaela. “Quellenkundliches zu Leben und Werk von Constantinus Africanus.” Deutsches Archiv für Erforschung des Mittelalters 59 (2003): 122–52.

Verger, Jacques. Les gens de savoir dans l’Europe de la fin du Moyen Âge. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1998.

Witt, Robert G. L’eccezione italiana. L’intellettuale laico nel Medioevo e l’origine del Rinascimento (800–1300). Rome: Viella, 2017.

Zipser, Barbara, and Petros Bouras-Vallianatos, eds. Brill’s Companion to the Reception of Galen. Leiden: Brill, 2019.

-

1 See below p. xx for examples from the field of late medieval Greek-Latin translations.

-

2 Students of Arabic, to name some important contributors as Dimitri Gutas, Dag Nikolaus Hasse, and Daniel G. König, made substantial advances in their specific research fields (I discuss König’s results below, some works of the other two are included among the references). Earlier researchers, such as Charles Homer Haskins, Marie Thérèse d’ Alverny and Walter Berschin analyzed Greek to Latin and Arabic to Latin translations between the eleventh and fourteenth centuries. Their results are partly summarized below.

-

3 Green, “Medical Books,” 277 and 281.

-

4 For an up-to-date overview of translations from Greek to Latin, consult Bara, “Greek Thought, Latin Culture.”

-

5 Haskins, Studies in the History of Medieval Science; Haskins, The Renaissance of the Twelfth Century; Benson and Constable, eds., Renaissance and Renewal in the Twelfth Century.

-

6 Cf. Bara and Toma, Latin Translations of Greek Texts, ix.

-

7 Haskins, Studies, 142, 156.

-

8 Angold, “The Norman Sicilian Court,” 147–49.

-

9 Becker, “Multilingualism.”

-

10 Haskins, Studies, 147–48.

-

11 For instance, Exarchos, Lateiner am Kaiserhof in Konstantinopel, 56.

-

12 d’Alverny, ‘Translations and Translators’; Berschin, Greek Letters and the Latin Middle Ages.

-

13 https://hiw.kuleuven.be/dwmc/research/al. Last accessed April 4, 2025.

-

14 Clagett, Archimedes in the Middle Ages.

-

15 Angold, “The Norman Sicilian Court”; Leemans, ed., Translating at Court.

-

16 Amerini and Galluzzo, A Companion to The Latin Medieval Commentaries on Aristotle’s Metaphysics.

-

17 Bydén and Radovic, The Parva Naturalia in Greek, Arabic and Latin Aristotelianism.

-

18 König, “Sociolinguistic Infrastructures,” 33–55.

-

19 König, “Sociolinguistic Infrastructures,” 17–20.

-

20 Gaul, Thomas Magistros und die spätbyzantische Sophistik, 125–31.

-

21 Giraud, A Companion to Twelfth-Century Schools.

-

22 De Ridder-Symoens, A History of the University in Europe, vol. 1, Universities in the Middle Ages.

-

23 Verger, Les gens de savoir, 9–48.

-

24 Giraud and Mews, “John of Salisbury and the Schools of the 12th Century.” See also Giraud, “La naissance des intellectuels au XIIe siècle.”

-

25 Witt, L’eccezione italiana.

-

26 Ferruolo, The Origins of University: The Schools of Paris and Their Critics.

-

27 Mounteer, “English Learning in the Late Twelfth and Early Thirteenth Century.”

-

28 Joachim Ehlers, “Die hohen Schulen.”

-

29 Lemerle, Byzantine Humanism.

-

30 Steckel and Grünbart, Networks of Learning.

-

31 Constantinides, Higher Education in Byzantium in the Thirteenth and Early Fourteenth Centuries.

-

32 Magdalino, The Empire of Manuel I Komnenos, 316–413.

-

33 Gaul, Thomas Magistros und die spätbyzantische Sophistik.

-

34 Bara, “Greek-Latin Translators on the Move, 1050–1200.”

-

35 Ciggaar, Western Travellers to Constantinople.

-

36 Discussed for instance in Nicol, Byzantium and Venice; Jacoby, Travellers, Merchants and Settlers in the Eastern Mediterranean; Laiou and Morrisson, Byzantium and the Other.

-

37 Cigaar, “Réfugiés et employés occidentaux au XIe siècle”; Rodriguez Suarez, “The Western Presence in the Byzantine Empire,” 28–47, 70–102. Military studies are relevant particularly in the case of Hugo Heteriano, about whom Antoine Dondaine suggested that he may had been an imperial bodyguard, see Dondaine, “Hugues Éthérien et Léon Toscan,” 73–74.

-

38 Shepard, Byzantine Diplomacy; Drocourt, Diplomatie sur le Bosphore.

-

39 Exarchos, Lateiner am Kaiserhof in Konstantinopel.

-

40 Rapp and Preiser-Kapeller, Mobility and Migration in Byzantium.

-

41 Such as Ebessen, “Jacques de Venise;” Nutton, “Niccolò in Context;” Exarchos, Lateiner am Kaiserhof in Konstantinopel, esp. 35–65.

-

42 Jaspert et al., Cultural Brokers at Mediterranean Courts; Exarchos, Lateiner am Kaiserhof in Konstantinopel. For “go-betweens” in the early modern period, see Höfele and Koppenfels, Renaissance Go-Betweens.

-

43 Fludernik and Gehrke, eds., Grenzgänger zwischen Kulturen.

-

44 Fidora, Die Wissenschaftstheorie des Dominicus Gundissalinus.

-

45 Urso, “In Search of Perfect Equivalence.”

-

46 Chiesa, “Ambiente e tradizioni.”

-

47 Berlier, “Niccolò da Reggio traducteur du De usu partium de Galien.”

-

48 Burnett, Gutas, and Vagelpohl, Why Translate Science?

-

49 Mártinez-Gázquez, The Attitude of the Medieval Latin Translators.

-

50 Bara, “Who Was the Author.”

-

51 Classen, Burgundio von Pisa.

-

52 Exarchos, Lateiner am Kaiserhof in Konstantinopel, esp. 119–29.

-

53 Copeland, Rhetoric, Hermeneutics, and Translation in the Middle Ages.

-

54 Forrai, “Hostili Praedo Ditetur Lingua Latina.”

-

55 Pratsch, Der hagiographische Topos.

-

56 Folliet, “La Spoliatio Aegyptiorum.”

-

57 Campbell, “The Politics of Medieval European Translation.”

-

58 Gassman, “Translatio Studii.”

-

59 Verger, Les gens de savoir, parts ii, iii; Gosman, “Alexander the Great as the Icon of Perfection.”

-

60 Le Goff, Les intellectuels; Verger, Les gens de savoir.

-

61 De Ridder-Symoens, A History of the University in Europe, vol. 1, iv.

-

62 E. g., Oldoni, “La promozione della scienza: L’ Università di Napoli”; Leemans, ed., Translating at the Court. On the notion of translators’ “self-sponsorship,” see Bara, “Greek-Latin Translators on the Move, 1050–1200.”

-

63 Forrai, “Hostili Praedo Ditetur Lingua Latina,” 128–33.

-

64 Burnett, Gutas, and Vagelpohl, eds., Why Translate Science?, 445–544.

-

65 Théry, “Documents concernant Jean Sarrazin.”

-

66 Federici Vescovini, Pietro d’ Abano tra storia e leggenda, 11–27.

-

67 Boethius. In Porphyrii Isagogen commentorum editio secunda, Chapter 1.

-

68 Burnett, “Translation and Transmission,” 354–56.

-

69 Delle Donne, “Un’ inedita epistola sulla morte di Guglielmo de Luna,” 225–38.

-

70 Kaska, “Zur hochmittelalterlichen Überlieferung von Maximus Confessor,” 221–39.

-

71 Beullens and De Leemans, “Aristote à Paris: Le système de la Pecia.”

-

72 Minio-Paluello and Dod, Analytica posteriora, vol. 1, xxxix. Another twelfth-century example is the Ethica vetus: of the 48 manuscripts, five are considered “root manuscripts” (Gauthier, Ethica Nicomachea, vol. 1, xxi).

-

73 Vuillemin-Diem, Metaphysica, lib. I-XIV, 55–115. See also Robert Grosseteste’s translation of the Nicomachean Ethics (recensio L): the 36 manuscripts are grouped into seven classes, each containing between three and seven witnesses (Gauthier, Ethica Nicomachea, vol. 1, clxxiv–lxxxvi).

-

74 McVaugh, “Galen in the Medieval Universities, 1200–1400,” 381–89.

-

75 Buytaert, De fide orthodoxa, ix–xv.

-

76 Chiesa, “Ambiente e tradizioni,” 540–42.

-

77 Jacob, “La traduction de la Liturgie de saint Jean Chrysostome,” 112–20.

-

78 Green, “Medical Books,” 279–86.

-

79 Beullens, The Friar and the Philosopher, 69–71.

-

80 Angold, “The Norman Sicilian Court.”

-

81 Leemans, Translating at Court, xii–xxviii.

-

82 Bara, “Greek Thought, Latin Culture,” 62–67.

-

83 Brams, La riscoperta di Aristotele.

-

84 Zipser and Bouras-Vallianatos, Brill’s Companion to the Reception of Galen.

-

85 Buytaert, De fide orthodoxa, xlviii–liii.

-

86 Burnett, “The Twelfth-Century Renaissance,” 367–68.

-

87 Bara, “Greek Thought, Latin Culture,” 22–61.

-

88 Steel, “Guillaume de Moerbeke et Saint Thomas”; Beullens, “A Methodological Approach,” 155–59.

-

89 Leemans, “Aristotle Transmitted,” 330–38.

-

90 Veit, “Quellenkundliches zu Leben,” 133.

-

91 Vuillemin-Diem and Steel, Ptolemy’s Tetrabiblos, 39–48.

-

92 Beullens, The Friar and the Philosopher, 77–82.

-

93 Dorandi, Diogenes Laertius, 9.

-

94 Durling, “Burgundio of Pisa and Medical Humanists,” 96–99.

-

95 Green, “Gloriosissimus Galienus,” 324–36.

-

96 Fortuna and Urso, “Burgundio da Pisa traduttore di Galeno,” 147–49.

-

97 Fidora, Die Wissenschaftstheorie, 23–97.

-

98 Fidora and Polloni, “Ordering the Sciences,” 115–30.

-

99 For instance, De Ridder-Symoens, A History of the University in Europe, vol. 1, iv.

-

100 McVaugh, “Galen in the Medieval Universities, 1200–1400,” 380–90.

-

101 Jacquart, “Principales étapes dans la transmission des textes de médecine”; Zipser and Bouras-Vallianatos, Brill’s Companion to the Reception of Galen.

-

102 https://www.galenolatino.com. Last accessed April 4, 2025.

-

103 Green, “Gloriosissimus Galienus.”

-

104 Lond, “Arabic-Latin Translations.”

-

105 Urso, “Translating Galen in the Medieval West.”

-

106 McVaugh, “Galen in the Medieval Universities, 1200–1400.”

-

107 See also above.

-

108 McVaugh, “Niccolò Da Reggio’s Translations of Galen and Their Reception in France,” 290–300.

-

109 For instance, Fortuna, “II Corpus delle traduzioni di Niccolò da Reggio,” 288.