Discipline and Superiority: Neurasthenia and Masculinity in the Hungarian Medical Discourse*

Gergely Magos

Eötvös Loránd University, Faculty of Social Sciences

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Hungarian Historical Review Volume 14 Issue 4 (2025): 588-614 DOI 10.38145/2025.4.588

“The nerve is still a mystery, which is why neurasthenia is in vogue,” wrote Viktor Cholnoky, the renowned Hungarian writer in 1904.1 Indeed, neurasthenia, a mental disorder considered a typically male ailment, was at the forefront of medical discourses in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, yet so far, it has largely escaped the attention of Hungarian medical historians. Neurasthenia can be interpreted through multiple analytical frameworks, and connections can be drawn between neurasthenia and experiences of modernization, nationalism, and social inequalities; the emergence of the middle class and consumer society; and the professionalization of psychology, among other factors. This paper aims to explore how neurasthenia, as a male mental disorder, was discussed in the Hungarian medical discourse in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. I argue that this medical concept contributed to the medicalization of male sexuality and also reinforced the existing social gender hierarchy. Male sexuality and male social roles are the focus of the paper, but I also briefly explore how anxieties over modernity and the perceived decline of the nation were linked to other male mental disorders, such as paralysis progressiva.

Keywords: neurasthenia, masculinity, male sexuality, medicalization

Masculinity and Neurasthenia

In a criminology article, police captain József Vogel described the case of a 26-year-old financial manager who became homosexual as a prisoner of war after World War I. Vogel claimed that prisoners with “weak nerves” often masturbated due to the lack of “normal sexual intercourse.” This behavior, he claimed, can induce neurasthenia. These men then would completely abandon “normal” sexual habits and turn to homosexuality.2

This case reminds us that sexuality has always been a subject of curiosity and, with the emergence of the modern sciences, also of scientific interest. As Michel Foucault suggested, society did not directly repress sexuality but rather made it a subject of knowledge. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the scientific discourse about sexuality served to control and regulate the body in the alleged cause of public health, productivity, and national progress.3 The pathologization of “abnormal” sexual behaviors, such as onanism or frigidity, established sexual norms for both women and men. Medical discourse incorporated female and male sexuality into biopolitical efforts, thereby establishing sexual norms necessary for fertility and “normal” marital sexuality.4

Medical concepts became an integral part of the discourses about humanity and its environment, which sought to capture social, political, and economic changes at the level of the body. Social pathologies were given a medical interpretation. The medical focus on the male body was closely connected to the emergence of modern notions of masculinity, which found expression in stereotypes reflecting social values and norms surrounding male body and psyche.5 Sexuality no longer exclusively served social reproduction, but, according to male bourgeois etiquette, it also had to satisfy the sexual needs of women. Male honor demanded that a husband be potent but also gentle within the confines of marriage.6 At the end of the nineteenth century, an alleged crisis of masculinity emerged as part of pervasive everyday experience. Women’s emancipation and the purported effeminization of men were considered the greatest threats to masculinity, along with the alleged crimes and forms of sexual deviance attributed to various minority groups, such as Jews. The perceived decline of masculinity was expressed in medical terms. Physical frailty or degenerated appearance were interpreted as symptoms of moral decay, sin, sexual aberrations, and, frequently, mental illness.7

Physicians identified sharp boundaries between purportedly normal sexuality and sexual deviance, which was seen as pathological. Yet the normalization of male and female sexuality took different forms, and their interpretation was based on gender essentialism. Male sexual over- or underperformance was referred to as onanism or impotence, and women were labeled as frigid or nymphomaniacal. These gendered interpretations of sexuality were explained with references to anatomical and biological differences, providing a “scientific” explanation of gender inequalities.8

The medicalization of male sexuality and especially masturbation is a well explored historical topic. In the eighteenth century, religious moral judgement of masturbation was replaced by scientific investigation.9 Nevertheless, masturbation continued to be regarded as the archetypal form of selfish, unproductive, deviant sexuality. The onanist was often accused of retreating into individualism and neglecting his role in national reproduction.10 A prevailing belief among physicians held that masturbation is harmful to health and potentially led to insanity.11

In the late nineteenth century, various medical diagnostic terms, including neurasthenia, were also closely associated with masculinity and male sexuality. The term neurasthenia was popularized by the American physician George M. Beard in the second half of the nineteenth century, and Beard’s influential work popularized the concept worldwide.12 The term, which is derived from Ancient Greek, literally means “weakness of the nerves.” The condition was viewed by medical experts as nervous exhaustion as a consequence of burdensome intellectual labor and overstimulation of the nervous system.13 It was closely associated with the emergence of modernization, as processes such as urbanization, industrialization, technological development, and the expansion of education, freedom and thus personal responsibility put additional stresses on the nervous system.14 According to Beard, in addition to the modern lifestyle and burdensome intellectual work, excessive sexuality or, in contrast, sexual continence or forced abstinence could cause neurasthenia.15

Beard felt that neurasthenia was a typically American ailment, and this, he believed, indicated the leading role of the American nation in the spread of modern civilization. The use of the term “Americanitis,” as neurasthenia was later labeled, was hardly a critique of modernity. Rather, it expressed a certain faith in the superiority of the American nation, which was allegedly marked by nervous sensitivity. These refined sensibilities, according to this theory, contributed to the rise of modern civilization, i.e., economic, technological, social, and political progress, and this in turn created further stimulation for the nervous system. This “vicious circle” made the American nation not only the custodian of modern civilization but, at the same time, paradoxically neurasthenic. Beard provided a medical legitimization for American exceptionalism, reinforcing the perceived hierarchy among nations.16 Moreover, neurasthenia served as an indicator of social inequalities within a society, since it was not equally widespread among different social strata. Its prevalence was closely linked to one’s proximity to modernity. Beard considered elite social groups, especially urban intellectual men, more susceptible to neurasthenia due to their deeper connection with modern civilization. In contrast, groups at the lower end of the social spectrum, such as “savage peoples” (African or Native Americans), the rural population, manual laborers, and women were perceived as less affected by the disease. Beard’s analysis could medically explain and validate the success of the social elite, suggesting that while Yankee businessmen and cultivated upper-class women benefited from modern progress, they bore a “high price” because of their susceptibility to neurasthenia.

Medical terms such as neurasthenia captured an understanding of the new modern male, a figure who was mentally stressed by the accelerated lifestyle and his obligations. This description of masculine identity was not limited to the United States. It soon gained international recognition, albeit in various forms. The adaptation of the term reflected local circumstances and was deeply intertwined with discourses about the nation.

In European discourses, neurasthenia expressed a fear of social decadence and the perceived decline and degeneration of nations and empires. In the British medical discourse, neurasthenia and other mental diseases thought to be more common among men were considered an important factor in the accelerating pace of national decadency.17 The disease came to be more frequently diagnosed in late nineteenth-century France in the context of growing concern about the decline of “true” manhood. Neurasthenia was regarded as an ailment caused by the cultural and moral weakness of men, exacerbated by urbanization and industrialization. This discourse intersected with national anxieties about France’s political and military power, suggesting that the “recovery” of masculinity, male emotional self-discipline, and physical strength could lead to the renewal of national vigor.18 In Spain, neurasthenia provided a medical description of “proper” masculinity, the decline of which was closely linked to the decline of the Spanish Empire. The medicalization of the decadent bourgeoisie male elite served to maintain their social status, while their vulnerability was presented as a main cause of the Spanish nation’s crisis.19 Concerns about masculine values and male sexual performance, intertwined with broader discourses about national strength and progress, appeared even in Russia, Japan, or Argentina.20

By the late nineteenth century, neurasthenia had also become a significant medical category in Central Europe. The German medical and broader discourse followed the international trends, and discussions of neurasthenia were intertwined with the perceived consequences of modernization. Between the 1880s and the 1910s, interpretations of the disease underwent a transformation. Physicians shifted from viewing nervousness as a mental stress to interpreting it as a sign of degeneration requiring biopolitical intervention.21 At the same time, neurasthenia became an integral part of the new bourgeois masculine identity, and diagnoses of neurasthenia were used to express everyday anxieties about sexual performance.22 In Austria-Hungary, the allegedly degenerative potentials of the ailment gained significance, and because of the Empire’s multiethnic composition, the disease was often employed to provide a medical explanation of ethnic differences and reinforce, under the guise of science, a “civilizational hierarchy” among nations. Neurasthenia was frequently presented as a disease of the Austrian-German bourgeois elite, while “Slavic” or “Eastern” nations were seen “too primitive” for neurosis.23 In order to arrive at a nuanced grasp of the Hungarian discourse, it is crucial to know the German and Austrian scientific contexts, as the concept of neurasthenia reached Hungary through the scientific literature in German.24

These analyses suggest that neurasthenia transcended mere medical description and became a crucial term through which social anxieties about masculinity and national identity were expressed. My objective in the discussion below is to present the medicalization of male sexuality in Hungary. To explore this, I analyze the discourse among the Hungarian physicians in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. I argue that while neurasthenia was part of the biopolitical discourse, it also served to provide discursive reinforcement of male social roles and, thus, social inequalities. The Hungarian medical discourse followed the international scientific arguments, reflecting a growing fear of degeneration and national decline. Perceived male sexual dysfunctions, namely excessive masturbation or impotence, were integral parts of the diagnosis. However, in Hungary, anxiety about national decline was expressed with a different diagnosis, namely a diagnosis of paralysis progressiva. As Michael S. Kimmel has suggested, the perceived crisis of masculinity often emerged when gender relations were under intensive transformation, and this notion of crisis was a tool that served to maintain the existing social hierarchy.25 The emerging bourgeois male identity, expressed in medical categories such as neurasthenia, was closely associated with modernity, intellectual capacity, and civilization. This stereotype of masculinity stood in sharp contrast with femininity, which was characterized as emotional, instinctive, and suggestible.

Medical and Organic Explanations in Hungarian Medical Discourse

Beard’s influential concept of neurasthenia reached the Hungarian medical community quickly through German translations. In 1881, Hungarian medical journals reviewed the German translation of Beard’s work on neurasthenia, which was originally published in 1880.26 The term was rapidly adopted, as shown by the fact that the 1883 Magyar Lexikon (Hungarian Lexicon) dedicated a separate article to neurasthenia, which was translated as “nervous weakness.”27

Hungarian physicians identified heredity as a significant factor in the development of the disease, establishing a relative consensus that neurasthenia is a pathological condition stimulated by external conditions. Jakab Salgó, a physician in the Royal National Asylum at Lipótmező in Budapest, the central asylum of Hungary, criticized those who described “nervousness” as a pandemic, suggesting that such views led to harsh criticism of “our familiar social institutions.” He contended that “nervousness is a disease, a pathological life process,” the prevalence of which is partly due to doctors’ better recognition of the disease.28

University professor Jenő Kollarits offered an organic explanation rooted in a different conceptual framework. He contended that nervousness is not a “disease” in the conventional sense, since this term covers externally acquired disorders. He claimed that nervousness is an inherited trait: “The character is made up of the chemical and physical features of the nervous system, which react according to the structure inherited from our ancestors. And the reaction is triggered by external circumstances and can be developed to a certain level, e.g. by education, but only within the individual’s capacity.”29 He called the deviation of the nervous system “heredoanomaly,” which could manifest as degeneration (heredodegeneration) or, in some cases, even amelioration or genius (heredoamelioratio). Therefore, both madness and genius were considered hereditary neurological conditions, while nervousness, including hysteria and neurasthenia, was interpreted as an inherited neurological predisposition.30

Fear of social degeneration also led to the emergence of eugenic discourses among physicians. University professor and forensic psychiatrist Ernő Moravcsik stated that between 60 and 70 percent of neurasthenic patients suffered from their condition because of hereditary reasons. According to him, the “pathological disposition” is also reflected in the degenerated physical appearance of the face and the deformity of the body, yet he claimed that this “degenerative condition […] could be ameliorated and eliminated over time through consistent interbreeding with healthier ones.”31 Ernő Jendrassik, a prominent neurologist and also a professor at University of Budapest and the director of Internal Medicine at the Budapest Hospital of the Brothers of Mercy, linked degeneration to various social pathologies or cults,

such as vegetarians, who without any rational reason live exclusively on plant food, and furthermore, they consume eggs and milk as plant food. Similar to them are the anti-alcoholics who were not alcoholics and who want to reform their fellowmen, but who are looking for victims not at the kiosks where spirits are sold, but among those who drink moderately.

Similar also are those who seek to reform humanity, and among them there are many who play a great role in the world, precisely because of these neurasthenic peculiarities or exceptional abilities.32

The ideas of the psychoanalytic school also bore strong affinities with this medical approach or organic explanation. Freud took an early interest in Beard’s theory and the concept of neurasthenia, as both of them attached great importance to sexuality in the genesis of the disease.33 According to Freud, “psychoneuroses,” including hysteria, phobia, or obsessional neurosis, were rooted in early psychosexual development. He distinguished the former category from “actual neuroses,” such as anxiety neurosis and neurasthenia. This latter term referred to the somatically induced distortion of sexual behavior, namely “onanism” and “coitus interruptus.”34 Freud argued that these “abnormal” sexual practices lead to self-intoxication, which weakens male sexual vigor. Meanwhile, he rejected the idea that the primary connection between masturbation and mental illness is psychological, a notion rooted in feelings of guilt or fear of social stigma.35 Sándor Ferenczi, Freud’s Hungarian friend and associate, agreed that neurasthenia is a “disease whose material carrier is undoubtedly some pathological alteration in the tissues of the nervous system.”36 Ferenczi explained neurasthenia as a consequence of autotoxicity (or self-intoxication) caused by excessive strain.37 According to him, the potential causes could be defecation issues, “self-poisoning with abnormal metabolites,”38 or the misdirected fulfilment or wasting of libido on an “inappropriate object.”39 He emphasized “excessive onanism,” which often occurs discreetly, such as when a patient fumbles with something in his pockets.40 In the conclusion to his essay, Ferenczi claimed that masturbation (and neurasthenia) manifests in symptoms such as diminished sexual potency and premature ejaculation. Ferenczi argued that, unlike in the case of hysteria, effective treatment for neurasthenia is the restoration of a “normal sexual life.”41

Thus, the Hungarian medical discourse on neurasthenia showed a broad consensus on two key points. First, it was generally accepted that the condition is rooted in somatic or pathological factors, with an inherited neurological predisposition often interpreted as degeneration. Some physicians directly linked bodily degeneration to social pathologies or decadence. Second, there was a shared conviction that external factors, such as sexual stimuli, trigger this disease, indicating that the nervous system is stressed beyond its inherent capacity.

Neurasthenia as a Male Disease

Hungarian physicians did not interpret neurasthenia as a male disease. Furthermore, the distinction between various forms of nervous disorders, such as hysteria, neurasthenia, or hypochondria, was viewed with skepticism.42 At the same time, however, it was also clear for some of them that in medical practice, there was a meaningful difference between hysteria and neurasthenia. Károly Laufenauer, the leader of the Department of Neurology and Psychiatry at the Budapest University, provided a thoughtful self-analysis of diagnostic practices and the social stereotypes reflected in the diagnoses of hysteria and neurasthenia. He defended women against the frequent and unjust accusation that they were the people primarily afflicted with nervousness:

I must rise to the defense of women who are so often and so unfairly attacked, as if the circle of women would establish the house and ground of nervousness. This is not the case, nervousness among women is no more common compared to men, and it is true that when we speak about very few hysterical men and many more hysterical women, we ignore the fact that we know of very few neurasthenic women and many more neurasthenic men. However, I have been convinced for many years, and no one will ever dissuade me, and I hope that this view will gain acceptance, that there is no difference between hysteria and neurasthenia; they are siblings, or even more than that, because these two names mean exactly the same thing and refer to the same disease.

For this reason, and perhaps because of opportunism, since to say someone is hysterical today is almost an insult, the term neurasthenia is more appropriate for women’s nervousness, thus, in a few years, we will see the dishonoring term hysteria disappear from the nomenclature of diseases to make way for the rightly and correctly applied name of neurasthenia for both sexes.43

Statistical evidence confirms Laufenauer’s contention that, contrary to widespread social belief, insanity was not a typically female condition. In Hungarian national asylums, men outnumbered women dramatically. Between 1899 and 1902, the ratio stood at 651 women for every 1,000 men in the asylums. Although this ratio shifted somewhat after World War I, a significant disparity remained. In 1918–1919, there were 724 women for every 1,000 male patients in state-owned national asylums.44 The population census reinforces this pattern from a different perspective, underscoring that, relative to Western and Northern European nations (such as Germany, the United Kingdom, and the Scandinavian and Baltic states), the preponderance of men in institutions for the mentally ill in Hungary was remarkable.45

Laufenauer’s reflections on the prejudices behind the disease categories are noteworthy, especially his views concerning the offensive nature of the term hysteria. The statistics reveal that, in clinical practice, women were predominantly diagnosed with hysteria, while men were more frequently labeled neurasthenic. Before World War I, the gender imbalance was striking. Among women, there were 17 times more patients diagnosed with hysteria, whereas men were represented 17 times more among neurasthenics. However, these diagnoses were relatively rare in asylums, with only 1.6–1.7 percent of patients diagnosed with hysteria and fewer than 1 percent with neurasthenia in the national asylums.46 The comparative rarity of these diagnoses may derive from the perception that such conditions were not particularly severe or threatening to individuals or society. Under the law, only those deemed dangerous were committed to asylums. Interestingly, in the 1920s, gender discrimination in these categories declined sharply, though it did not disappear.47

It is also worth noting that Jews were heavily overrepresented among the mentally ill in asylums. Before World War I, Jews comprised about 5 percent of Hungary’s population, yet the constituted 15 percent of those diagnosed as mentally ill and 30 percent of those diagnosed as neurasthenics. In other words, almost one in three individuals diagnosed with neurasthenia was Jewish.48 For a more complex analysis, it would be interesting to see how the diagnosis of neurasthenia varied across different socio-professional groups, although data on this subject is scarce. However, the striking overrepresentation of Jews is revealing, as they were a highly educated group with a strong urban background, perceived as successful in economic and intellectual endeavors. Thus, based on these data, the cautious conclusion can be drawn that neurasthenia was applied as a descriptive framework of the social elite both in discourse and in medical practice.

Male Sexuality

Most physicians associated both neurasthenia and hysteria with sexuality. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, physicians increasingly linked both conditions to sexual behavior, focusing on masturbation as a central theme in their explanations of mental illnesses. The morally loaded term “onanism” was transformed from a religious concern into a medical issue that was allegedly connected to various forms of abnormality and insanity.49 The somatization of masturbation was used to explain the practice, which was thought of as a form of male “madness,” a clear reflection of the attitudes of the era toward sexuality.50

For men, there were two primary forms of allegedly “abnormal” sexuality: the decline of sexual vigor and the improper indulgence of the libido. The former referred to conditions such as impotence and premature ejaculation, while the latter included behaviors such as masturbation, promiscuity, and sex with prostitutes. This description of madness served to emphasize a socially approved framework of male sexuality characterized as heterosexual, vigorous, and monogamous.

Jakab Salgó identified adolescence and sexual maturation as a critical turning point when nervous symptoms often emerged.51 During this transition period, intensified sexual stimuli and desires could lead to excessive sexual needs, causing symptoms of neurasthenia, such as masturbation and exhibitionism. Flirtatious girls kissed boys and used clothing and jewelry to adorn themselves, while boys were allegedly prone to committing perverted sexual acts. Salgó contended that asexual behavior and a lack of libido were also abnormal and should also be understood as signs of neurotic disease. The interplay between strong sexual desires and neurotic sensitivity could lead to complex emotional states, including bitterness, world-weariness, and suicidal ideation. Salgó’s notions combined medical analysis with moral condemnation, implying that deviations from expected sexual behavior were often tied to broader violations of moral standards, including behaviors such as lying, adopting a vagabond lifestyle, and stubborn and selfish conduct, which, Salgó contended, contributed to the transgression of legal and moral rules.

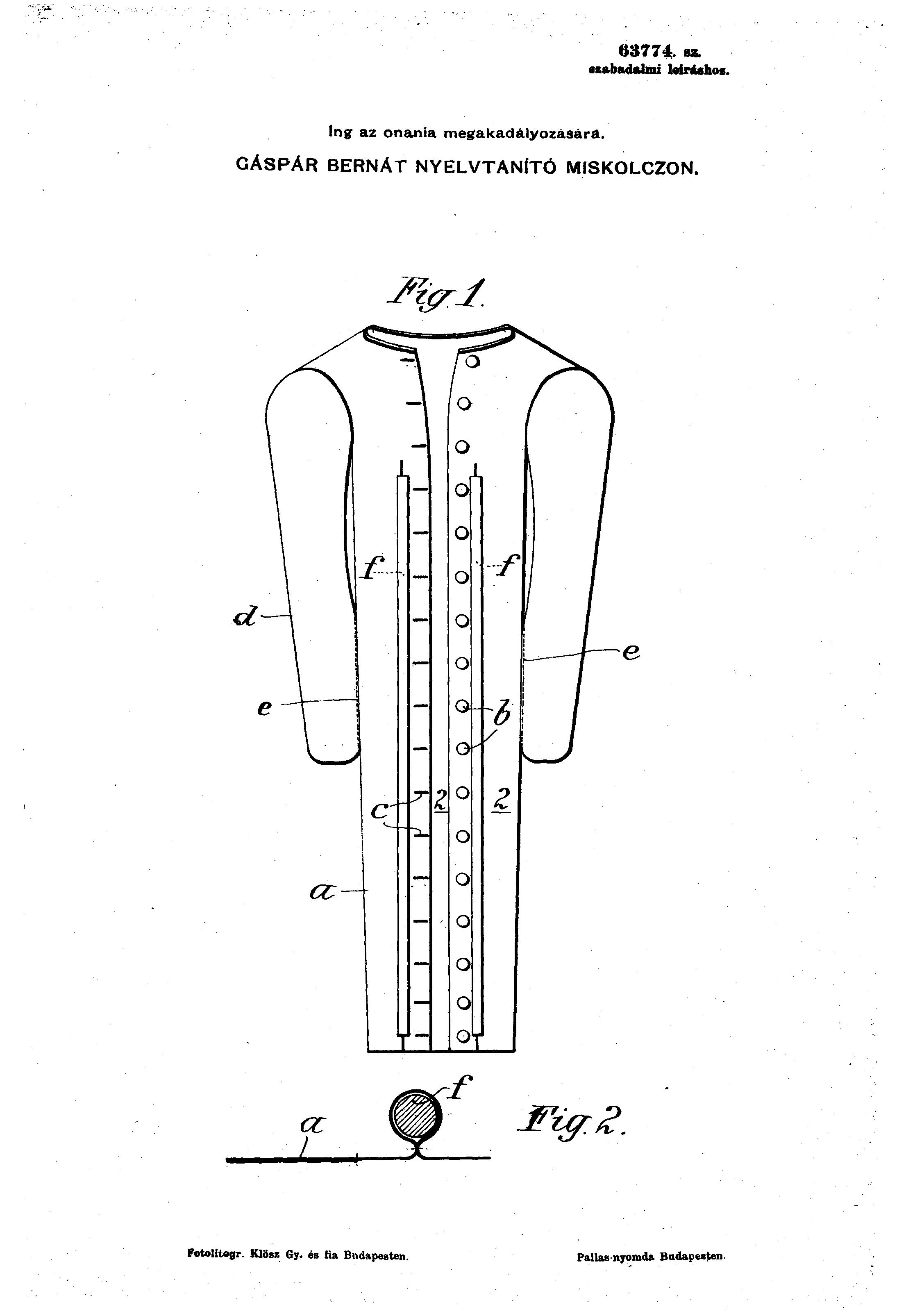

Kornél Preisich, a famous private pediatrician, offered advice for parents who sought to prevent onanism among children.52 He encouraged them to make it impossible for the children to move, which essentially meant tying them up. He also proposed that children should not be left alone before bedtime, and they should not be given blankets or, if they were given a blanket, then they should be required to keep their hands above it. This strict moral judgment surrounding “self-pollution” permeated society, revealing the widespread conviction that it was necessary to regulate sexuality. Other specialists and professionals, in addition to physicians, were involved in this practice of social control.53 Innovations emerged within educational circles to create garments specifically designed to prevent masturbation, such as the anti-onanism shirt patented by Hungarian teacher Bernát Gáspár in 1914.

In the contemporary medical discourse, masturbation, which came to be regarded as the most obvious sign of neurasthenia, was mostly associated with young men, if, however, not regarded as an exclusively “male” sin. The use of the term onanism, a pejorative synonym for masturbation, implied that women were excluded from this issue, since they were incapable of committing the “sin of Onan.”54 Onanism almost exclusively referred to male masturbation in the contemporary medical discourse.

Figure 1. A specifically designed shirt for preventing onanism. Magyar Királyi Szabadalmi Hivatal,

63774. lajstromszámú szabadalom (1900) [Royal Hungarian Patent Office, patent no. 63774].

https://library.hungaricana.hu/hu/view/SZTNH_SzabadalmiLeirasok_063774 Accessed September 2, 2025

Sexual neurasthenia,55 another term introduced by Beard, referred to a condition specific to men and occurring in midlife. It was characterized by a lack of sexual vigor, impotence, and an inability to have fulfilling and satisfying sexual intercourse. Miksa Weinberger, a Hungarian balneologist, claimed that approximately 30 percent of the cases of neurasthenia were linked to sexual issues, and he categorized male sexual difficulties as a subset of neurasthenia when somatic causes were absent.56 He identified two subtypes. The first was the “pathological waste of semen,” which meant promiscuous and licentious behavior and masturbation. The distinctive syndromes were called “pollutio” and “spermatorrhoea.” Weinberger emphasized the physiological aspect of this behavior, i.e., the remorse and guilt felt by the onanist after he has committed his “sin.” But at the same time, Weinberger also emphasized that his intention was not “to deny the harmful consequences of onanism,” which causes “fatigue and hypersensitivity of the nervous system in the brain, as well as the spinal cord.”57 The second subtype, called “impotentia coeundi,” referred to sexual underperformance, including the lack of libido, erectile dysfunction, and premature ejaculation. Weinberger argued that the psychological cause of this disease is performance expectations and the fear of failure. As one of his patients complained, “when he began his honeymoon, he was frightened that he might not be able to perform coitus, and this thought dominated him so much that he did not even get an erection in response to the sensual excitement he was seeking.”58

Károly Hudovernig, the head of the Psychiatric Department at Szent János Hospital, highlighted the vulnerability of middle-aged, unmarried men, who decided to settle down and get married. Such men have doubts concerning their sexual performance, and they fear that they might not be able to satisfy their wives’ sexual needs. Symptoms such as masturbation, sexual abstinence, excessive sexuality, and involuntary “pollution” (ejaculation, nocturnal emission) were common. Hudovernig noted that many of his patients blamed their condition on their earlier sex lives, which had included careless affairs, which had ultimately led to “the decline of male vigor.”59 These men

were not the enemies of an active sex life, but saw it simply as a series of accidental and vagabond episodes; their whole life had passed without any serious affection or more or less permanent liaison, and their sexual lives had consisted only of sporadic coitus each time with a different medium, for certain individuals more frequently than for others, therefore they sought and found the objects of their sexual satisfaction among the public or private loose women60 at all times, and because of their age and the trends in sexual pleasures, they often sought the exciting and perverse manipulations of these professional sex objects. […] they regarded the accidental female partner only as a natural and public canal for sexual arousal and needs.61

Hudovernig considered male promiscuity and a restrained sex life (asexuality or the loss of libido) medical issues. However, he rejected Freudian theory, which explains everything in terms of sexuality. However, he completely agreed with the notion that there was no reason to seek any somatic cause of neurasthenia. Neurasthenia, he believed, was a psychological issue caused by anxiety and fear surrounding sexual performance. The doctor’s job was thus to “relieve the psyche from the incubus.”62

Although Weinberger and Hudovernig were also heavily involved in the medicalization of male sexuality, their more sophisticated approach took into consideration the psychological and social aspects of sexuality. A notable aspect of this medical discourse is that many Hungarian physicians, familiar with the Freudian theory, sought to combine somatic therapies with psychoanalysis. However, the application of psychoanalysis met an ambivalent response. Many practitioners dismissed it, regarding it as a reductionist explanation that linked mental illness solely to psycho-sexual development. Weinberger argued that treatments such as balneotherapy (a therapeutic practice that uses bathing in mineral-rich waters, thermal springs, mud, or gases as a form of health treatment) would be ineffective if psychoanalytical methods were not also incorporated. He encouraged physicians to study patients’ “background, lifestyle, family circumstances, and potential occupational problems.”63 One of his contemporaries, urologist Mór Porosz, who worked at the Department of Dermatology and Venereology at the University of Budapest, employed faradization (electric stimulation) of the prostate as a somatic treatment, but he also believed that neurasthenia was caused by guilt often felt by men after certain sexual activities, such as masturbation or failures in sexual performance.64 Porosz cited one of his patients, who expressed deep shame after masturbation: “I felt disgusted with myself for my miserable, uncontrollable passion. […] When I was alone, I reproached myself loudly. […] I became a big misanthrope, and misogynist.”65 Porosz argued that while masturbation did not generate pathological changes, it created a disturbance in mood driven by guilt. Despite this psychological explanation, Porosz was convinced that the faradization of the prostate could be the best treatment to solve the core problem, namely excessive libido.66 In this case, the guilt felt by the patient may have been in response to his fear of judgement and social stigma. Masturbation was considered a “disgusting activity” by society, and these kinds of widespread social norms may well have caused the patient’s sense of frustration and shame.

Some physicians argued that neurasthenia could turn a heterosexual into a homosexual or could find expression in other “abnormal” sexual practices. “Life produces many indescribable variations,” one of them wrote.67 Sexual “aberrations” such as homosexuality, fetishism, and masochism were connected to neurasthenia.68

The medical discourse on neurasthenia reveals that male sexuality was subjected to a scrutiny similar to the scrutiny to which female sexuality was subjected in the discourse on hysteria. Any deviation from medically defined “normal” male sexual performance was deemed pathological, regardless of whether the underlying cause was classified as physical or psychological. The latter interpretation often labelled socially nonconformist behaviors and emotional tensions as pathological. Tensions surrounding sexual underperformance were frequently dismissed as unfounded anxiety or phobia, revealing the pervasive medicalization of male sexuality. The aforementioned Ernő Jendrassik noted the interesting case of a 17-year-old boy, who was sent to different doctors to cure his “pollution” (nocturnal emission):

Three years ago (he was only 14 years old!), the patient was sent “pro coitu” [to have sexual intercourse]69 by his family members. The serious young man did not like this encouragement, nor did he masturbate. With all this in mind, I asked the boy what unpleasant consequences he feels because of pollution. To which he replied in total denial, and at the same time he added, that “both the doctor and the specialist were surprised that I didn’t have any problem. They said, I should have.” Isn’t this the most obvious neurasthenic upbringing?70

Jendrassik’s question, which is phrased in the form of a rebuke, reveals that he blamed the other doctors because of the approach they took to the treatment of harmless “pollution.”

These contemporary studies illustrate how medical discourse maintains social differences and inequalities between genders. The discourse about neurasthenic men underscores a double standard, often referred to as Freud’s “double sexual morality,” which imposed severe social restrictions on female sexuality.71 The imperative of preserving female virginity shows this moral disparity. Promiscuous women and especially prostitutes were objectified and stigmatized as the “disgusting and infectious canal” of male sexual needs.72 Social expectations or obligations diverged for men who, if resorting to prostitution or masturbation, faced social condemnation and the consequent burden of guilt. As the sources clearly show, this dual morality gave men the latitude to lead a promiscuous sex life while also imposing on them a social obligation to identify themselves with “normal” masculinity and embody a masculine identity. Men who failed to meet these expectations were often labeled insane or neurasthenic.

Neurasthenia and Male Roles in Society

The term neurasthenia was closely linked not solely to male sexuality but also to the social roles assigned to men, and this understanding of the ailment reflected the values, norms, expectations, and stereotypes that were associated with masculinity. The differences between the ways in which neurasthenia was understood and diagnosed and the ways in which hysteria was diagnosed offer insights into the ways in which the medical discourse of the time reinforced social differences between men and women. In 1926, Ferenc Völgyesi, a renowned physician and hypnotizer,73 explained his view of the distinction between the “neurasthenic male psyche” and the “hysterical female psyche” in a widely read advisory book:

The hysterical type is definitely closer to primordial nature. She is quick-witted, instinctive in all her actions. Her spiritual life is overwhelmingly emotional. For her, logic, common sense, reason, truth, rationality are unknown and non-existent concepts, and to confront her with them is clearly unreasonable. […] she is receptive and reproductive, which means that she is passive, less autonomous and not made for productivity, for creating new things and not for organizing. […] In contrast, the fact is that the neurasthenic, more masculine spiritual type does not think with his “heart” as she does, but “always with his head.” […] The hysterical one can swim in happiness, carouse, have fun and enjoy the pleasures in life, while the neurasthenic one, being a light sleeper who lies awake all night compared to the former, goes to bed at night not sleeping the sleep of the just, but full of worries about what tomorrow will bring (the hysterical one simply doesn’t care). […] The hysterical one can be and therefore must be governed, not by logical arguments, but by hetero-suggestion, by the imperative and uncontroversial “declarations” of others, sometimes by reasonable force. It goes without saying that this is also dominant in the case of hysterical children, and this distinction is even more important in

parenting than in adult governance. In contrast, the neurasthenic one doesn’t respect any dogma or authority. […] The neurasthenic one only really believes what he feels and is convinced of as a logical truth, but he believes it fanatically and to the end.74

Völgyesi’s summary clearly reveals both the contemporary cultural stereotypes attached to men and women and also the power imbalance between men, women, and children. He describes women as emotional, instinctive, reproductive, careless, a bit naive and simple, like children, who can be easily manipulated or hypnotized and who thus need to be governed by men, who are rational, intellectual, independent, productive, and determined and therefore hold responsibility for the whole family. This paternalistic view suggests that male nervousness, captured in the concept of neurasthenia, is linked to the social expectation placed on men as breadwinners.

The aforementioned Károly Laufenauer offered another revealing insight into gender roles, arguing that neurasthenia is linked to men’s family life and work. His description affirms the patriarchal structure of family:

The most common cause of this nervousness [evolving in married life] is excessive intellectual work, effort without rest, as we say, a very rampant eagerness. It cannot be denied that the married status drives men to work more than the unmarried status. There is a psychological reason behind this; the person who starts a family lives not only for the present but also for the future, thinking of his children, of the possible reduction of his own workforce, and this constantly pushes him to acquire wealth to ensure the existence of his family. Therefore, the first and main concern of every careful wife should be that the head of the family not overwork himself and follow a suitable work schedule.75

Salgó was convinced that every illness has a somatic cause. He also agreed, however, that “intense, exhausting and devouring, physical and intellectual work” put a strain on the nervous system, which could lead to nervousness, especially in individuals whose nervous systems are “less developed.”76 Since this midlife nervousness, which often culminated in a mental crisis, was often connected with everyday struggles, its root was different. For men, burdensome work and the struggle to play the role of the breadwinner contributed to the disease, while for women, the exhausting experiences of childbirth and parenting played an important role. Interestingly, Salgó emphasized that it was not physical labor that exhausted men. Rather, it was the demands of intellectual work that could be debilitating.77 In his book A szellemi élet hygiénája (The Hygiene of Mental Life), he argued that paralysis progressiva78 (another disorder considered to affect primarily men at the time) was closely connected with intellectual activities such as education or office work, which could overstimulate the brain.79 Salgó noted that the people who were most frequently diagnosed with paralysis were members of social groups who had to face overwork (surmenage) alongside family issues, or in other words, married male intellectuals and office workers between 35 and 40 years of age. Men’s social and family duties as breadwinners protected women from the strains of everyday struggles, according to Salgó: “Marriage takes a burden off the woman’s shoulders, and this finds expression in the small number of [cases of] paralyses [among women].”80 Salgó cynically added that the social transformation of the time, namely female emancipation, had caused an increase in the number of women diagnosed with paralysis. This fact, he claimed, “may add a few drops of bitterness to the goblet of feminism’s successes.”81 He remarked that the feminist movement and revolution had had casualties: “No wonder that this sharp and ruthless war, into which women have entered with more zeal and enthusiasm than preparation and practice, affects women with its worse consequences. No great social transformation can be achieved without victims.”82

As Salgó’s argument exemplifies, like the medicalization of femininity, the creation of exclusive medical categories such as neurasthenia and paralysis, with which women were rarely diagnosed, also served to maintain gender inequalities. These gender differences were also reflected in social values. The medical concepts were adopted (and possibly created) presumably in part because they offered medical explanations for differing social roles and obligations. Jakab Fischer, a physician in Bratislava, cited an illuminating case. One of his female patients complained about her husband, who had been diagnosed by Fischer with neurasthenia. The wife reported that her husband “avoids companionship, cares little for his family, his clothes are sloppy, and he is more wasteful than before […] He cannot do his work, not only because he tires very quickly, but because he already shows the symptoms of memory lapses. His memory is worsening.”83 As her description makes clear, a normal, healthy man was sociable, hardworking, thrifty, and elegant, or at least took care to dress appropriately.

Physicians of the time claimed that men played a leading role in developing civilization, albeit at a considerable cost to their mental wellbeing. Ernő Moravcsik went back to the Beardian concept, claiming that

it puts an increased strain on the brain, when the rapid development and progress of all fields of science, art, literature, industry, and commerce requires the acquisition of a wider and more intensive knowledge, it shows various ways of acquiring wealth, material wellbeing and pleasure, it aggravates the struggle for existence together with the growing demands, it stimulates increased physical and mental activity, and it brings a series of material and mental crises and convulsions during changing circumstances.84

At that point, the global progress of civilization acquired a localized shape in the medical discourse, tying it to the struggles of the Hungarian nation. Unlike empires such as the United Kingdom, the United States, or Spain, the decline of Hungary was framed not within the context of imperialism but rather as a matter of relative backwardness. According to medical analyses, the general progress of civilization and development in Western countries led to “growing demand and aspirations” in Hungary, thereby placing additional pressures on people to “chase wealth.”85 However the gap between desires and economic conditions was too large, and thus only individuals who invested additional intellectual and physical efforts were able to satisfy their needs. Physicians stated that this relentless pursuit often culminated in mental health issues, namely paralysis. This disease, which was seen as affecting only male patients, was conceptualized as the “Hungarian insanity.”86 István Hollós, a physician in the Royal National Asylum at Lipótmező who became later a famous psychoanalyst, found that, while in Western Europe a mere 10 percent of those who had been diagnosed as mentally ill suffered from paralysis, in Hungary, this figure reached nearly 30 percent. Hollós blamed the snobbery of the Hungarian middle classes, coupled with their ambition to appear better than they actually were.87 Salgó provided a similar social explanation for this phenomenon, claiming that the Hungarian nation had embraced the same needs and desires as its more advanced Western counterparts. Yet, due to historical reasons, Hungarian society struggled to accumulate the sufficient capital to fulfill these aspirations:

We possess all the advancements and comforts that the development of science and taste has brought to humanity, and all the mental and physical pleasures that only the most sophisticated culture could have developed. Our soul and body are not only capable of the finest pleasures, but also desire them. However, we are not strong enough to obtain them, to satisfy our sophisticated desires. […] The wide gap between our aspirations and our strength is the reason why we stimulate our strength too hard, thus presenting ourselves as gentlemen.88

Physicians highlighted their responsibility to recover the “most important” figure of the workforce, the educated man. Their task was not merely to help the suffering patients, but also to reinvigorate them and facilitate their reintegration into society. Salgó argued that

nervous exhaustion is more than a mere medical issue; it has evolved into a social issue. […] It is clear that the well-understood interests of society require that adequate provisions be made for low-income or penniless nervous patients. This is not dictated by the much clichéd slogan of humanity, but by public interest. […] The poorer we are in material goods, the stronger should be the conviction that the true and inalienable wealth of any nation is the human being and his capacity for work. The money we spend on them is money saved.89

In support of this biopolitical approach, Fischer emphasized the substantial value of human capital. He argued that “the state’s most valuable wealth lies in its human resources. This is not only a humanistic but also an economic thesis. Furthermore, as health is the most valuable for the people, it follows that the most important interest of the state is to improve, develop, and preserve the health of its citizens. Consequently, the state’s most important objective must be healthcare.”90

Conclusion

The medical discourse on neurasthenia seems controversial. Historically, it was linked to male vigor and performance, both sexually and occupationally. Male sexuality was strictly disciplined, and any deviation from “normal” sexuality or behavior, such as masturbation, premature ejaculation, promiscuity, asexuality, impotence, or homosexuality, was categorized as an aberration or anomaly. These deviations were often described as pathological conditions requiring somatic treatment. In several cases, the hereditary predisposition of the nervous system was cited as the underlying cause of an abnormal sexual libido, which could lead to behaviors deemed undesirable, such as masturbation. However, a closer examination of the descriptions offered in specific medical cases reveals that the anxiety experienced by many young patients derived from fear of social stigma. Numerous cases illustrate that these individuals did not perceive themselves as ill. Rather, their sexuality was labeled as abnormal by their families or by the medical authorities. While psychological explanations spread among physicians, the pathological explanation remained predominant.

A similar argument can be seen in the case of men’s work. Any deviation from the expected performance was viewed as a medical issue. Men who were industrious or exceptionally accomplished were labelled potential victims of neurasthenia. It is worth noting that this aspect of the discourse served to reinforce existing social hierarchies, inequalities, and power dynamics at the discursive level. Neurasthenia came to be seen as a sign of superiority, industriousness, modernity, geniality, and intellectual potential, qualities which stood in sharp contrast with the nature of female hysteria. Women were often described as emotional, instinctive, suggestive, and needing to be governed by men. In this context, the significance of men’s work was highlighted in the medical texts. According to the contemporary medical discourse, the work performed by men not only maintained the family financially but also put additional strains on men’s nervous systems.

This description is loaded with moral implications. It clearly suggests that jobs requiring intellectual engagement, such as teaching, art, law, and public office, are the most dangerous for men’s health. The responsibilities associated with these professions extended beyond mere economic subsistence. They were understood as contributions to humanity as a whole. Thus, the medical discourse on neurasthenia reveals not only how this condition was understood as a consequence of individual struggles but also how it was used to buttress broader social values and power structures, ultimately shaping the understanding of masculinity in the given historical context.

* Supported by the EKÖP-24 University Excellence Scholarship Program of the Ministry for Culture and Innovation from the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund.

Bibliography

“A psychosexualis impotentia analytikai értelmezése és gyógyítása” [The analytical understanding and therapy of psychosexual impotence]. Orvosi Hetilap 52, no. 47 (1908): 867–68.

Abbey, Susan E. and Paul E. Garfinkel. “Neurasthenia and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: The Role of Culture in the Making of a Diagnosis.” The American Journal of Psychiatry 148, no. 12 (1991): 1638–46. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.12.1638

Beard, George M. and Alphonso D. Rockwell. Sexual Neurasthenia (Nervous Exhaustion): Its Hygiene, Causes, Symptoms and Treatment with a Chapter on Diet for the Nervous. New York: E. B. Treat, 1884.

Beard, George M. American Nervousness: Its Causes and Consequences, a Supplement to Nervous Exhaustion (Neurasthenia). New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1881.

Biró, József. A neurasthenia sexualis és a latens tuberculosis [Neurasthenia sexualis and latent tuberculosis]. Budapest: Pesti Lloyd Társulat, 1913.

Budai (Bauer), Kálmán. Kenotoxin és Neurasthenia [Kenotoxin and neurasthenia]. Budapest: Brózsa Ottó Könyvnyomda, 1911.

Bullough, Vern L. and Martha Voght. “Homosexuality and Its Confusion with the ‘Secret Sin’ in Pre-Freudian America.” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 28, no. 2 (1973): 143–55.

Cheyne, George. The English Malady (1733). Edited by Roy Porter. London–New York: Routledge, 2013.

Campbell, Brad. “The Making of ‘American’: Race and Nation in Neurasthenic Discourse.” History of Psychiatry 18, no. 2 (2007): 157–78. doi: 10.1177/0957154X06075214

Cholnoky, Viktor. “Betegségdivatok” [Disease trends]. A Hét, September 18, 1904.

Dickson, Melissa, Emilie Taylor-Brown, and Sally Shuttleworth. “Introduction.” In Progress and Pathology: Medicine and Culture in the Nineteenth Century, edited by Melissa Dickson, Emilie Taylor-Brown, and Sally Shuttleworth, 1–24. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2020.

Ferenczi, Sándor. A hisztéria és a pathoneurózisok: Pszichoanalitikai értekezések [Hysteria and pathoneuroses: Psychoanalytic essays]. Budapest: Dick Manó, 1919.

Ferenczi, Sándor. “A neurastheniáról” [About neurasthenia]. Gyógyászat 45, no. 11 (1905): 164–66.

Ferenczi, Sándor. A pszichoanalízis rövid ismertetése [A brief summary of psychoanalysis]. Budapest: Animula, 1997.

Fischer, Jakab: “A neurasthenia és a paralysis progressiva kezdő szakasza” [Neurasthenia and the early stage of paralysis progressiva]. Gyógyászat 45, no. 12 (1905): 180–82.

Fischer, Jakab. “Elmebetegügy Magyarországon” [Insanity in Hungary]. Közegészségügyi Szemle 1, no. 8–9 (1890): 615–623.

Forth, Christopher E. “Neurasthenia and Manhood in fin-de-siècle France.” In Cultures of Neurasthenia, edited by Marijke Gijswijt-Hofstra and Roy Porter, 329–61. Leiden: Brill, 2001.

Foucault, Michel. Abnormal: Lectures at the College de France 1974–1975. London–New York: Verso, 2003.

Foucault, Michel. The History of Sexuality. Vol. 1, An Introduction. New York: Pantheon Books. 1978.

Freud, Sigmund. “‘Civilized’ Sexual Morality and Modern Nervous Illness.” In The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud. Vol. 9, (1906–1908): Jensen’s ‘Gradiva’ and Other Works, edited by James Strachey, 177–204. London: Vintage, 2001.

Frühstück, Sabine. “Male anxieties: nerve force, nation, and the power of sexual knowledge.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 15, no. 1 (2005): 71–88.

Groenendijk, Leendert F. “Masturbation and Neurasthenia: Freud and Stekel in Debate on the Harmful Effects of Autoerotism.” Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality 9, no. 1 (1997): 71–94. doi: 10.1300/J056v09n01_05

Goering, Laura. “Russian Nervousness: Neurasthenia and National Identity in Nineteenth-Century Russia.” Medical History 47, no. 1 (2003): 23–46.

Gyimesi, Julia. “Hypnotherapies in 20th-Century Hungary: The Extraordinary Career of Ferenc Völgyesi.” History of the Human Sciences 31, no 4 (2018): 58–82.

Hare, E. H. “Masturbatory Insanity: The History of an Idea.” Journal of Mental Science 108, no. 452 (1962): 1–25.

Hofer, Hans-Georg. Nervenschwäche und Krieg: Modernitätskritik und Krisenbewältigung in der Österreichischen Psychiatrie (1880–1920). Vienna–Cologne–Weimar: Böhlau Verlag, 2004.

Hollós, István. Adatok a paralysis progressivához Magyarországon [Data on paralysis progressiva in Hungary]. Budapest: Schmidl Sándor könyvnyomdája, 1903.

Hudovernig, Károly. A sexualis neurasthenia egy alakja előrehaladottabb korban [A form of sexual neurasthenia in advanced age]. Budapest: Brózsa Ottó Nyomdája, 1912.

Jendrassik Ernő: “A neurastheniáról” (Part 2) [About neurasthenia]. Orvosi Hetilap 49, no. 30 (1905): 523–25

Jendrassik Ernő: “A neurastheniáról” (Part 6) [About neurasthenia]. Orvosi Hetilap 49, no. 34. (1905): 588–90.

Jendrassik, Ernő. “Általános idegbajok” [General nervous disorders]. In A belorvostan tankönyve [The textbook of internal medicine], vol. 2, edited by Ernő Jendrassik, 369–462. Budapest: Universitas, 1914.

Kaufmann, Doris. “Neurasthenia in Wilhelmine Germany: Culture, Sexuality, and the Demands of Nature.” In Cultures of Neurasthenia from Beard to the First World War, edited by Marijke Gijswijt-Hofstra and Roy Porter, 161–76. Amsterdam–New York: Rodopi, 2001.

Kimmel, Michael S. “The Contemporary ‘Crisis’ of Masculinity in Historical Perspective.” In The Making of Masculinities: The New Men’s Studies, edited by Harry Brod, 121–53. Boston: Allen & Unwin, 1987.

Kollarits, Jenő. Jellem és idegesség [Charakter and nervousness]. Budapest: Orvosi Könyvkiadó Társulat, 1918.

Lafferton, Emese. “The Hygiene of Everyday Life and the Politics of Turn-of-the-Century Psychiatric Expertise in Hungary.” In Psychology and Politics: Intersections of Science and Ideology in the History of Psy-Sciences, edited by Anna Borgos et al., 239–54. Budapest–New York: Central European University Press, 2019.

Laqueur, Thomas W. Making Sex: Body and Gender from the Greeks to Freud. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1990.

Laqueur, Thomas W. Solitary Sex: A Cultural History of Masturbation. New York: Zone, 2003.

Laufenauer, Károly. Előadások az idegélet világából [Lectures about the realm of the nervous system]. Budapest: Természettudományi Könyvkiadó Vállalat, 1899.

Magyar Lexikon: Az egyetemes ismeretek encyklopaediája [Hungarian Lexicon. Encyclopedia of universal knowledge]. Vol 12. Budapest: Wilckens és Waidl, 1883.

Magyarország elmebetegügye az 1899 évben. Közzéteszi a M. Kir. Belügyministerium [Insanity in Hungary in 1899. Published by the Hungarian Royal Ministry of Internal Affairs]. Budapest: Scmidl Sándor Könyvnyomdája, 1900.

Milne-Smith, Amy. Out of His Mind: Masculinity and Mental Illness in Victorian Britain. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2022.

Moravcsik, Ernő. A neurasthenia. (Idegesség) [Neurasthenia. Nervousness]. Budapest: Pfeifer Ferdinánd, 1917.

Moose, George L. The Image of Man: The Creation of Modern Masculinity. New York–Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1996.

Nye, Robert A. “Honor, Impotence, and Male Sexuality in Nineteenth-Century French Medicine.” French Historical Studies 16, no. 1 (1989): 48–71.

Porosz, Mór. “Az onania következményeiről” [About the consequences of onanism]. Gyógyászat 45, no. 10 (1905): 149–51.

Preisich, Kornél. “Az egészséges és beteg gyermek” [Healthy and sick children]. In Az egészség enciklopédiája: Tanácsadó egészséges és beteg emberek számára [Encyclopedia of health: Advice for healthy and sick people], edited by József Madzsar, 41–82. Budapest: Enciklopédia Rt, 1926.

Radkau, Joachim. “The Neurasthenic Experience in Imperial Germany: Expeditions into Patient Records and Side-looks upon General History.” In Cultures of Neurasthenia from Beard to the First World War, edited by Marijke Gijswijt-Hofstra and Roy Porter, 199–217. Amsterdam–New York: Rodopi, 2001.

Roelcke, Volker. “Electrified Nerves, Degenerated Bodies: Medical Discourses on Neurasthenia in Germany, circa 1880–1914.” In Cultures of Neurasthenia from Beard to the First World War, edited by Marijke Gijswijt-Hofstra and Roy Porter, 177–97. Amsterdam–New York: Rodopi, 2001.

Ruiz, Violeta. “Neurasthenia, Civilisation and the Crisis of Spanish Manhood, c. 1890–1914.” Theatrum Historiae, no. 27 (2020): 95–119.

Ruggiero, Kristin. Modernity in the Flesh: Medicine, Law, and Society in Turn-of-the-Century Argentina. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2004.

Salgó, Jakab. A szellemi élet hygiénája [The hygiene of mental life]. Budapest: Franklin-Társulat, 1905.

Salgó, Jakab. Az idegességről [About neurasthenia]. Budapest: Lampel, 1907.

Schmiedebach, “The Public’s View of Neurasthenia in Germany: Looking for a New Rhythm of Life.” In Cultures of Neurasthenia from Beard to the First World War, edited by Marijke Gijswijt-Hofstra and Roy Porter, 219–38. Amsterdam–New York: Rodopi, 2001.

Schuster, David G. Neurasthenic Nation: America’s Search for Health, Happiness, and Comfort, 1869–1920. New Brunswick, NJ–London: Rutgers University Press, 2011.

Straus, Stephen E. “History of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome.” Reviews of Infectious Diseases 13, Suppl. 1 (1991): 2–7.

Szasz, Thomas. “The Medicalization of Sex.” Journal of Humanistic Psychology 31, no. 3 (1991): 34–42.

Szél, Tivadar. “Az elmebetegség mint, tömegjelenség. I. közlemény” [Insanity as mass phenomenon. Part I]. Magyar Statisztikai Szemle 7, no. 5 (1929): 453–76.

Szél, Tivadar. “Az elmebetegség mint, tömegjelenség. II. rész” [Insanity as mass phenomenon. Part II]. Magyar Statisztikai Szemle 7, no. 6. (1929): 489–614.

Vogel, József. “Homosexualitás” [Homosexuality]. In A modern bűnözés I [Modern crime I], edited by Gyula Turcsányi, 115–52. Budapest: Rozsnyai Károly Kiadása, 1929.

Thewrewk, István. “A magyar elmebaj” [Hungarian insanity]. Pesti Napló, April 17, 1910.

Vargha, Dóra. “A bűn medikalizálása” [The medicalization of crime]. Budapesti Negyed 13, no. 47–48 (2005): 166–98.

Völgyesi, Ferenc. “A hipnózis, szuggesztió, hisztéria és neuraszténia” [Hypnosis, suggestion, hysteria, and neurasthenia]. In Az egészség enciklopédiája: Tanácsadó egészséges és beteg emberek számára [Encyclopedia of health: Advice for healthy and sick people], edited by József Madzsar, 340–58. Budapest: Enciklopédia Rt, 1926.

Weinberger, Miksa. “A neurasthenia gyógyítása intézetekben és fürdőhelyeken” [Treatment of neurasthenia in institutes and bath]. Gyógyászat 39, no. 21 (1899): 324–27.

Weinberger Miksa. A neurasthenia sexualis gyógyitásáról [About the treatment of sexual neurasthenia]. Budapest: Franklin-Társulat, 1902.

Zachar, Peter and Kenneth S. Kendler. “Masturbatory Insanity: The History of an Idea, Revisited.” Psychological Medicine 53, no. 9 (2023): 3777–82.

-

1 Cholnoky, “Betegségdivatok,” 609.

-

2 Vogel, “Homosexualitás,” 121–22.

-

3 Foucault, The History of Sexuality.

-

4 Foucault, Abnormal.

-

5 Moose, The Image of Man.

-

6 Nye, “Honor, Impotence.”

-

7 Moose, The Image of Man, 56–76.

-

8 Laqueur, Making Sex.

-

9 Szasz, “The Medicalization of Sex.”

-

10 Laqueur, Solitary Sex.

-

11 See Hare, “Masturbatory Insanity”; Zachar and Kendler, “Masturbatory Insanity.”

-

12 Beard, Neurasthenia. Though term neurasthenia was not coined by Beard, he made it a popular medical concept. See Campbell, “The making of ‘American’,” 160.

-

13 Nowadays, neurasthenia is considered in medical literature a predecessor of chronic fatigue syndrome. See Straus, “History”; Abbey and Garfinkel, Neurasthenia.

-

14 Beard, American Nervousness, 171–73. This association between modernization and mental diseases was hardly new. Beard’s concept is closely linked to George Cheyne’s work written in the early eighteenth century. See Cheyne, The English Malady.

-

15 Beard and Rockwell, Sexual neurasthenia.

-

16 Schuster, Neurasthenic Nation; Campbell, “The making of ‘American’”; Dickson et al., “Introduction.”

-

17 Milne-Smith, Out of His Mind, 221–23.

-

18 Forth, “Neurasthenia and Manhood.”

-

19 Ruiz, “Neurasthenia,” 98.

-

20 Ruggiero, Modernity in the Flesh; Goering, “Russian nervousness”; Frühstück, “Male anxieties.”

-

21 Kaufmann, “Neurasthenia”; Roelcke, “Electrified Nerves”; Schmiedebach, “The Public’s View.”

-

22 Radkau, “The Neurasthenic Experience.”

-

23 Hofer, Nervenschwäche.

-

24 Moavcsik, “Könyvismertetés.”

-

25 Kimmel, “The Contemporary ‘Crisis’ of Masculinity.”

-

26 Moravcsik, “Könyvismertetés.”

-

27 Magyar Lexikon, 591–92.

-

28 Salgó, Az idegességről, 5.

-

29 Kollarits, Jellem és idegesség, 93–96.

-

30 This idea fits well into the contemporary cult of the genius. Kollarits founded his approach on Cesare Lombroso’s Genio e follia (Genius and insanity), which was translated into Hungarian in 1906. Kollarits, Jellem és idegesség, 12.

-

31 Moravcsik, A neurasthenia, 15.

-

32 Jendrassik, “A neurastheniáról, part 2,” 523.

-

33 Beard and Rockwell, Sexual neurasthenia.

-

34 Groenendijk, “Masturbation,” 73–74.

-

35 Ibid., 86–87.

-

36 Ferenczi, “A neurastheniáról,” 17.

-

37 The concept of autotoxicity was quite popular at the time. See Budai, Kenotoxin; Biró, A neurasthenia sexualis.

-

38 Ferenczi, “A neurastheniáról,” 18; Ferenczi, A hisztéria, 39–46.

-

39 Ferenczi, A pszichoanalízis, 32.

-

40 Ferenczi. “A neurastheniáról,” 18; Ferenczi, A hisztéria, 39–46.

-

41 Ferenczi, A pszichoanalízis, 26–31.

-

42 Kollarits, Jellem és idegesség, 143.

-

43 Laufenauer, Előadások, 176–77.

-

44 Szél, “Az elmebetegség II,” 600. Other sources confirm these data, see for example: Magyarország elmebetegügye az 1899 évben.

-

45 Szél, “Az elmebetegség I,” 462.

-

46 Szél, “Az elmebetegség II,” 607.

-

47 Ibid., 608.

-

48 Ibid., 604; 611.

-

49 Hare. “Masturbatory insanity.”

-

50 Foucault, Abnormal, 59–60, 227–57.

-

51 Salgó, Az idegességről, 20–23.

-

52 Preisich, “Az egészséges,” 57.

-

53 Magyar Királyi Szabadalmi Hivatal, 16997. lajstromszámú szabadalom (1914) [Royal Hungarian Patent Office, patent no. 16997] https://library.hungaricana.hu/hu/view/SZTNH_SzabadalmiLeirasok_016997 Accessed September 2, 2025.

-

54 The term onanism derives from the Bible, although it is based on a misinterpretation of Onan’s interrupted sexual intercourse. Bullough and Voght, “Homosexuality,” 145–46.

-

55 Beard and Rockwell, Sexual neurasthenia.

-

56 Weinberger, A neurasthenia sexualis.

-

57 Ibid., 6–7.

-

58 Ibid., 13.

-

59 Hudovernig, A sexualis neurasthenia.

-

60 “Vulgivaga” is a medieval neo-Latin term used to denote allegedly promiscuous women (as it refers, according to its Latin roots, to “wandering among the common people”). It was also used as a euphemistic name for prostitutes.

-

61 Hudovernig, A sexualis neurasthenia, 4–5.

-

62 Ibid., 7–8.

-

63 Weinberger, “A neurasthenia gyógyítása,” 326.

-

64 Porosz, “Az onania.”

-

65 Porosz, “Az onania,” 150–51.

-

66 “A psychosexualis impotentia.”

-

67 Moravcsik, A neurasthenia, 33.

-

68 Jendrassik, “Általános idegbajok,” 456.

-

69 Or in other words, he was sent to gain sexual experience, presumably among prostitutes.

-

70 Jendrassik, “A neurastheniáról, part 6,” 590.

-

71 Freud, “Civilized Sexual Morality.”

-

72 Vargha, “A bűn medikalizálása.”

-

73 On the extraordinary career of Völgyesi, see Gyimesi, “Hypnotherapies.”

-

74 Völgyesi, “A hipnózis,” 355–57.

-

75 Laufenauer, Előadások, 174.

-

76 Salgó, Az idegességről, 6–7.

-

77 Lafferton, “The Hygiene,” 242–46.

-

78 Today, it is called syphilitic paresis or GPI (general paralysis of the insane), which is a mental disease caused by syphilis.

-

79 Many doctors argued that the symptoms of neurasthenia and paralysis are very similar, and it is difficult to distinguish between the two diseases. See, for example, Fischer, “A neurasthenia”; Jendrassik, “Általános idegbajok,” 458.

-

80 Salgó, A szellemi élet, 144.

-

81 Ibid., 142.

-

82 Ibid., 143.

-

83 Fischer, “A neurasthenia,” 3–4.

-

84 Moravcsik, “A neurasthenia,” 17.

-

85 Weinberger, A neurasthenia gyógyításáról, 324.

-

86 Thewrewk, “A magyar elmebaj.”

-

87 Hollós, Adatok a paralysis progressivához.

-

88 Salgó, A szellemi élet, 149.

-

89 Salgó, Az idegességről, 62–64.

-

90 Fischer, “Elmebetegügy Magyarországon,” 3.