On Mad Dogs and Their Relation to Human Medicine: The Discourse on Canines in  Nineteenth-Century Medical Studies in Porto

Nineteenth-Century Medical Studies in Porto

Monique Palma

Universidade Aberta Portugal; Interuniversity Center for the History of Science and Technology

(CIUHCT), Nova University of Lisbon

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.; This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Hungarian Historical Review Volume 14 Issue 4 (2025): 563-587 DOI 10.38145/2025.4.563

This study offers a discussion of the presence of non-human animals, specifically dogs, in the studies of Porto doctors in the nineteenth century. It emphasizes the relationship between humans and dogs in the context of rabies contamination, using inaugural dissertations presented to the Porto Medical and Surgical School as primary sources. This work offers a contribution to an emerging historical overview of the “One Health” movement, which was established in the twentieth century but has roots in earlier periods. The paper argues that there were other elements in the fight against rabies, a zoonosis that troubled Portuguese society in the period covered by this article and required a multiplicity of actions by human medicine, veterinary medicine, the population, and political authorities to manage effective solutions to combat the disease. It offers an illustrative example of how the organization of human society is not shaped solely by humans, as the analysis of the relevant historical sources reveals the prominent, if indirect, role of other non-human animals in shaping social structures. The theoretical and methodological framework of this work is grounded in the history of science and environmental history.

Keywords: history of science; history of medicine; environmental history; non-human; animals and human medicine; medical knowledge

Things go even further: reason is completely lost; sometimes it’s a sweet, sad, melancholic madness; sometimes there are passing fits of incoherence; persecution mania, and there are patients who can’t resist suicide; finally, the disturbances can be less severe and there is nothing but extravagance of ideas and language; in women, hysterical madness is frequent.1

This is a medical description of rabies symptoms from the end of the nineteenth century in the city of Porto, Portugal. The disease, sometimes confused with episodes of madness, terrified Portuguese society, endangered the population, and triggered a strong mobilization among human and non-human animals for its effective control.

This study examines the role of dogs as one of the primary vectors in the transmission of rabies to humans2 and also the uses to which dogs were put in the development of prophylactic measures against the rabies virus in Portugal, with particular emphasis on the city of Porto in the nineteenth century, a period marked by the consolidation of changes initiated in the previous century.3 Even today, we remain aware that the primary mode of rabies transmission to humans is through the bite of an infected dog.4

The transmission of rabies occurs through interspecies interaction. In the Portuguese context of the nineteenth century,5 political authorities relied on the support of a society immersed in a landscape of transformations within the medical field. During this period, medicine, religion, and methods of treating illness increasingly diverged, driven by a series of technological innovations that laid the foundation for clinical medicine.6

At the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Carlos Alberto Salgado de Andrade defended and presented at Escola Médico-Cirúrgica do Porto his inaugural dissertation, entitled “Ligeira Contribuição para o Estudo da Raiva” (A small contribution to the study of Rabies in Portugal).7 He argued that “rabies is an infectious-contagious disease,8 originating in the dog, and transmitted by infection to all warm-blooded animals.”9 According to the newly graduated physician, since it was a disease originating (or at least thought to originate) in the dog, “in order better to understand the danger wherever it may exist and to avoid it as much as possible, we will study rabies in humans and in dogs, successively.”10

At this point, it is important to note that this article is not a study in human medicine aimed solely at the human species. I aim to contribute to the perspective that supports the “One Health” initiative. Sarah J. Pitt and Alan Gunn state in the paper One Health Concept (2024)11 that this framework constitutes a comprehensive approach to the study and management of infectious diseases, recognizing the intricate interdependence among humans, animals, plants, and the environment. Where does this concept originate? Pitt and Gunn demonstrate that in the mid-twentieth century, the American veterinary scientist Calvin Schwabe (1927–2006) first analyzed the parallels between human and animal health and welfare, introducing the concept of “One Medicine.” He underscored the importance of an integrated and multidisciplinary perspective from which veterinary professionals could contribute to the broader field of medicine. Epidemics among animals, known as epizootics, can also have an impact on humans.12

Schwabe further emphasized the relevance of incorporating the social sciences and developing effective communication strategies to foster community engagement in efforts to prevent and control infectious diseases. In the early twenty-first century, this concept evolved to encompass the health of entire ecosystems, including plants, wildlife, and geographic regions. The publication of the Manhattan Principles on Conservation in 2004 advocated for a holistic understanding of the dynamic interactions between humans and animals. The global outbreak of the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV-1) from 2002 to 2004 further demonstrated the significant risks that zoonotic diseases pose to human populations. It was around this period that the term “One Health” was formally introduced, marking the consolidation of a unified vision for addressing human, animal, and environmental health within an integrated framework.13

This understanding of human health as interconnected with the health of the environment and other animals predates the formal establishment of the concept.14 The case of Carlos Alberto Salgado de Andrade mentioned in the paragraph above offers a clear illustration of this. The relationship between humans and other animals has changed significantly in recent years, yet the interaction itself, as well as the advantages and disadvantages of such coexistence, is not new in history. Especially in the context of zoonoses, although Andrade has argued that “this subject belongs more to Veterinary Medicine than to Human Medicine, I have no doubt, nevertheless, in presenting here some considerations that may help us understand rabies in this animal, which is almost always the source of transmission to humans.”15 Consequently, the fight against the virus that causes rabies requires joint measures, as can be observed both historically and in the present day. This is what was proposed by the foundation of the “One Health” initiative, which calls for coordinated actions to address challenges that impact the stability of human health.16

Likewise, disease control takes place through interactions or “interspecies encounters,” as argued by Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing in her 2015 book The Mushroom at the End of the World.17 Among diverse human and non-human conditions, as well as within particular ecosystemic configurations, forms of collaboration are made possible, often reflected in the shaping of structures and dynamics oriented toward the needs of the human species. Thus, the prevention of many diseases (including the prevention of the spread of many diseases), among them rabies, calls for joint efforts between human medicine and veterinary medicine.

This allows us, via an analysis of nineteenth-century Portuguese discourses on rabies, to contribute to a more nuanced understanding of the historical roots of the “One Health” perspective. Rabies is recognized as the only Neglected Tropical Disease (NTD)18 that can be effectively prevented through vaccination. Studies on rabies in any field, such as history, can help highlight the importance of vaccines. The disease has been considered eradicated in Portugal since 1961, with the last autochthonous case recorded in the country in 1960. Although Portugal only officially declared eradication decades later, its case followed the broader European context of disease elimination of autochthonous cases,19 as seen in Denmark (1889), Scandinavia (before 1900), Austria (1914), Germany (1914 and subsequently in 1939), the United Kingdom (1922), the Netherlands (1923), the former Czechoslovakia (1930s and 1940s), and Hungary (1930s and 1940s).20

In Portugal, disease control was achieved primarily through the mandatory vaccination of dogs, established by Decree No. 11242 in 1925.21 Eradication has been the result of a successful and well-implemented vaccination program, in which politics, medicine, veterinary science, and society committed themselves to controlling and combating the spread of the rabies virus. In the Netherlands and Germany, the first legislation aimed at controlling rabies in dogs and cats dates back to 1875 and 1880, respectively.22

To address my objective, the article first provides an overview and contextualization of rabies research with regard to the case analyzed in this study. It then presents the sources and background information on the medical training institution of the physicians and authors under study and provides an analysis of how dogs are referenced in works concerned with the understanding of human medicine, as well as how rabies is discussed in the contexts of the connection between dogs, humans, medicine, and medical knowledge. Through this structure, I hope to identify traces of an early initiative that emphasized the need for efforts that value the connection between the various components of the ecosystem shared by the human species.

By addressing aspects of the “One Health” approach, I use historical research as a direct tool to understand and address the challenges of the present. The existence and trajectory of diseases have a significant impact on society. They drive changes within human communities, leading to the emergence of technological and pharmaceutical innovations aimed at promoting health. Diseases foster interaction among various agents,23 including physicians, policymakers, and non-human actors, such as dogs, who are used in the development: of solutions from which society as a whole may benefit.

Rabies and Non-Human Animals in Context

The nineteenth century was a period of profound transformation in medicine. The transition era marked a break with earlier practices, enabling the implementation of new procedures, a shift that has been well recognized in the secondary literature.24 From Hippocratic-Galenic to clinical medicine, the agents serving the field of medicine, physicians, surgeons, and pharmacists entered a period marked by the emergence and/or identification of new diseases,25 as well as new forms of treatment.

In Portugal, surgery began to be institutionally recognized in relation to medicine, at least formally, in the eighteenth century, in part as a result of the measures implemented by the Marquis of Pombal and the reforms of the University of Coimbra.26 However, within the medical sphere, it is evident that this equivalence did not occur immediately, despite being established on paper.27 Only in the nineteenth century can we observe this integration taking place in a more consistent manner, also driven by the abandonment of medical theories that had previously underpinned medical thought and practice. Across the globe, the late eighteenth century marked the conclusion of various processes and the beginning and recognition of different organizational systems across multiple areas of society.28

There is no stage of this transformative period that was carried out solely through human activity. Although historical investigation cannot rely on documentary sources produced by other agents involved in the changes that took place over the centuries discussed here, human-produced sources allow us to inquire into and perceive the presence of these other vectors, such as dogs, in medical writings. In this sense, the case of rabies stands out as a compelling example of the relationship between humans and dogs.

As Abigail Woods states in the book coedited by her entitled Animals and the Shaping of Modern Medicine: Medicine and Biomedical Sciences in Modern History published in 2018,29 rabies has received considerable attention and prominence in historical scholarship. It is a disease transmitted by the animal known in many cultures as “man’s best friend,” and it prompted decisions and public health interventions ranging from prophylaxis to the extermination of dogs showing symptoms of rabies. In Portugal, in her study Allies or Enemies? Dogs in the Streets of Lisbon in the Second Half of the Nineteenth Century,30 Inês Gomes examines the duality inherent in human coexistence with non-human animals, particularly dogs, whereby an animal regarded as a loyal and faithful companion could, when afflicted with rabies, become a deadly threat.

Woods points to historical studies on rabies in different parts of the world during the same period addressed in this article, including South Africa,31 the United States of America,32 and the United Kingdom,33 in which the dog, along with other disease-transmitting animals, appears as a key vector in understanding the history of rabies.34 Observations regarding the connections between human and animal health are longstanding, and the study of the history of rabies is a relevant and significant topic within this field. One reason for this is the fact that “rabies kills”35 is more than just a slogan, and thus, this is one of the key factors that led the World Health Organization (WHO) to establish World Rabies Day in 2007, observed annually on September 28.36

In Portugal, as shown by historiography and sources explored in the article, the first anti-rabies vaccination took place in Lisbon on January 25, 1893.37 Previously, individuals who had been bitten by rabid animals were sent to Paris, which represented a significant financial investment by the state and a considerable personal effort on the part of the patient. In Lisbon, the first institution to carry out these vaccinations was founded on March 9, 1895. The institution was the Real Instituto Bacteriológico de Lisboa (Royal Bacteriological Institute of Lisbon), with Professor Luiz da Câmara Pestana38 serving as its first director. In northern Portugal, the Pasteur Institute of Porto was inaugurated in 1896,39 just three years after the establishment of the Lisbon institute.

However, as Carlos Alberto Salgado de Andrade notes in his inaugural dissertation, the institute in Porto did not receive any formal funding: “This Institute, without any official support and solely through the initiative of the esteemed clinician Dr. Arantes Pereira, was inaugurated.”40 Before the founding of the Institute in Porto, Alexandra Esteves and Sílvia Pinto explain that patients from northern Portugal had to travel to Lisbon, bringing with them the head of the animal, already dead, so that tests could be conducted to verify the presence of the rabies virus.41

Figure 1. Decree (Ministry of Public Works – Diário do Governo No. 287,

December 17, 1886). Available at: https://legislacaoregia.parlamento.pt/V/1/60/68/p916 (accessed November 12, 2025).

The prevention of the spread of rabies among humans depends on the control of rabies in dogs,42 as the high incidence of the disease was due to attacks by rabid dogs.43 In Lisbon, as early as 1876, there was a directive that mandated a 60-day quarantine in suspected cases and the culling of the animal if rabies was confirmed.44 With regard to the Portuguese State, on December 16, 1886, a decree was issued (Ministry of Public Works, Diário do Governo, no. 287, dated December 17, 1886) approving the organizational plan for livestock services. Among various provisions, the decree included proposals that outlined “Hygienic and Sanitary Police Services for Animals.”45 The document identified epizootic diseases and zoonoses that should be monitored as a prophylactic measure for public health.

Rabies was either included among the group of diseases attributed to specific animals or, in some cases, to all animals. It ranked third in the table listing the “common nomenclature of diseases,” in which all animals were classified under the category of “animal species subject to sanitary regulation.”

At the end of the nineteenth century, the physician Eduardo Abreu was sent by the Portuguese administration, by the Ministry of the Kingdom, to Paris to study the development of the rabies vaccine.46 He eventually became the target of criticism from fellow medical professionals because of the way he conducted experiments on animals, and they questioned Abreu’s understanding of chemical and medical process. Although it has been found that Eduardo Abreu had limited contact with Louis Pasteur, he was undeniably one of the key figures behind the transformative actions of the period under discussion, as already discussed in the secondary literature. He was one of the acknowledged agents in the medical policy measures adopted in Portugal for the control and prevention of rabies.

Regarding Louis Pasteur, historian of medicine and biomedical sciences José Pedro Sousa Dias, in his analysis of the reception of Pasteur’s work, emphasizes that the absence of formal medical education posed significant obstacles in Pasteur’s engagement with the medical community. There are records suggesting that the early stages of Pasteur’s work were accelerated precisely by the fact that he was working with animals and veterinarians. However, once he began engaging with the medical profession, he encountered obstacles that stemmed, in part, from the conservativism and resistance to change that characterized many members of the medical establishment at the time.47

The development of laboratory techniques, new treatment methods, and medications that support human medicine is the result of interdisciplinary efforts. Veterinary medicine played a prominent role in the nineteenth century, as it continues to do today, in the control of zoonoses, such as rabies. Veterinarians were essential in drafting reports and administering vaccines. Nevertheless, as Alexandra Isabel Gomes Marques recounts in her doctoral dissertation, there was a heated debate in the Chamber of Deputies48 aimed at discussing the reorganization of the Bacteriological Institute of Lisbon, which was expected to establish structures for the development of treatment against diphtheria.49

Some of the key figures involved in the debate (for instance, physicians João Franco and António Teixeira de Sousa), although they did not dismiss the contributions of veterinarians, did not support the integration of these professionals into the reform of the Institute. Elvino de Brito, a veterinary physician who advocated for the creation of a specific post for a veterinarian within the Institute, also held differing political affiliations. João Franco and António Teixeira de Sousa belonged to the Regenerator Party,50 while Elvino de Brito was a member of the Progressive Party. To summarize the episode, which is skillfully analyzed by Marques, the reorganization of the Institute did not include the integration of veterinary professionals in the development of diphtheria treatment. In an ironic twist of fate, not long thereafter, Câmara Pestana himself acknowledged having relied on the assistance of a veterinarian to produce the anti-diphtheria serum.51

In late nineteenth-century Portugal, the study and control of rabies reflected broader transformations in the medical science and public health. Figures such as Eduardo Abreu and Luís da Câmara Pestana played important roles in adopting bacteriological methods inspired by Louis Pasteur, despite professional disputes and institutional resistance. The tensions between physicians and veterinarians, which came to the forefront in the debates over the reorganization of the Lisbon Bacteriological Institute, revealed the interdisciplinary challenges and political divisions shaping scientific progress in this period. Human medicine, veterinary medicine, and the environment are strongly interconnected within the public health policy agenda.52 The coexistence of human and non-human within their ecosystems gives rise to interspecies encounters, which foster the emergence of diseases, the development of medicines, new technologies, and new areas of activity within human society.53

The Discourse on Dogs in the Inaugural Dissertations Presented

at the Porto Medical-Surgical School

The primary corpus of sources used in this study consists of a set of inaugural dissertations,54 53 of them, written between 1867 and 1899 and defended and presented at the Porto Medical-Surgical School (EMCP). The school was founded in 1836, and in 1911, upon its integration into the Polytechnic Academy, became part of the University of Porto.55 The texts are currently accessible in the Digital Repository of the University of Porto,56 providing a rich collection for studies in the history of medicine.57 The authors of these dissertations are not prominent figures of Portuguese medicine. Little is known about them. Rather, they are marginalized and overlooked individuals in the historiography of medicine, yet they left behind valuable records that allow us to delve into public health policies and the evolution of medical thought during a profoundly transformative period.58

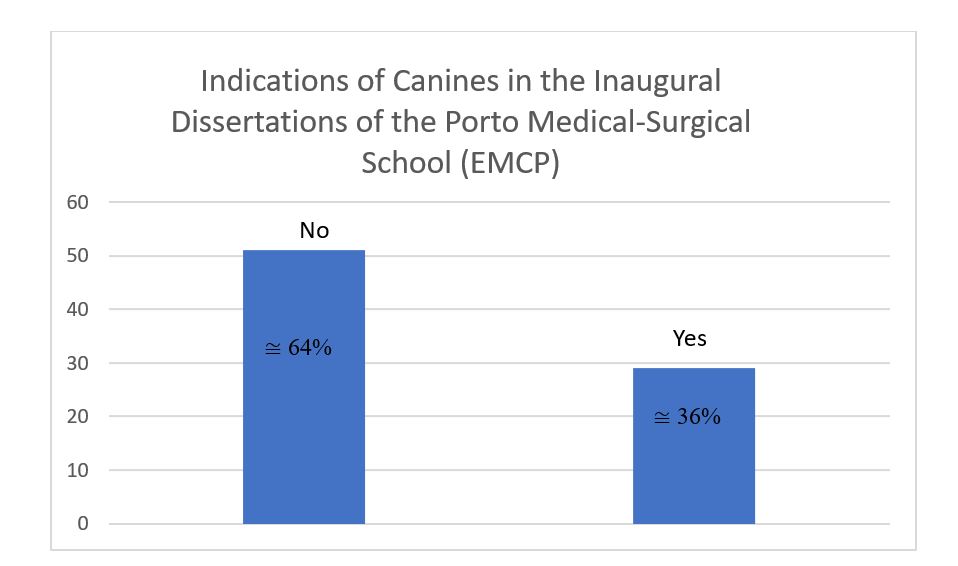

In all the dissertations under discussion, references to dogs are generally and predominantly though not exclusively associated with rabies. The subject of rabies and dogs also appear in studies that are not directly dedicated to the disease itself, and they are only mentioned as a subsidiary topic. This is the case with the dissertation by João Machado de Araújo, “Breve estudo sobre asepsia em cirurgia” (A brief study on surgical asepsis), defended in 1875,59 the text of Francisco José de Sousa’s “Algumas palavras sobre a opotherapia: tratamento de certas doenças por extractos d’orgãos animais” (Some remarks on opotherapy: the treatment of certain diseases using extracts from animal organs), 1899;60 and the thesis of António Augusto Chaves de Oliveira’s “Estudo sobre os diversos systemas de remoção das immundicias adoptados nas principaes cidades da Europa e sua applicação à cidade do Porto” (Study on the various systems of waste removal adopted in the principal cities of Europe and their application to the city of Porto), defended in 1866.61 Dogs are present in approximately 36 percent of the medical dissertations focused on human medicine that we have analyzed thus far.

Figure 2. Index of the presence of dogs as a subject in the Inaugural Dissertations

Presented at the Porto Medical-Surgical School

Within the collection of works, there are also direct references to rabies in the titles of the dissertations. This is represented by the case of Miguel Carlos Moreira, who defended his dissertation “A Raiva: (estudo historico, clinico e prophylactico)” (Rabies: (historical, clinical, and prophylactic study)62 in 1897 and the case of José da Costa Silva Júnior, who presented “Breve estudo sobre a prophylaxia da raiva” (A brief study on rabies prophylaxis)63 in 1889.

In the case of studies on rabies, it is not surprising to find references to dogs, as they are the primary vectors of transmission to humans and thus appear prominently in works concerning human medical treatment. In dissertations that are not exclusively focused on rabies, certain elements from the tendencies of nineteenth-century medicine can be identified, a context I have emphasized in the thesis statement of this article. What these dissertations mirror is that in the nineteenth century, medicine increasingly incorporated laboratory-based analytical technologies, which helps explain the inclusion of non-human animals, such as dogs, in studies of human medicine. In most cases, these references relate to experiments carried out on these animals.

The inaugural dissertations also support the perception that, within the parameters of Portuguese medicine during the period under analysis, the pace of developments occurring throughout nineteenth-century Europe was being followed. Arnaud Tarantola, in his volume Four Thousand Years of Concepts Relating to Rabies in Animals and Humans, Its Prevention and Its Cure,64 which was published in 2017, points out that extensive experimental work was carried out on the immunization of animals, giving us the example of the German city of Jena in 1804, where physician Georg Gottfried Zinke experimentally transmitted rabies without a bite by applying the saliva of rabid dogs to the tissues of animals. A similar experiment took place in 1813, conducted by Hugo Altgraf zu Salm-Reifferscheidt. Beyond immunization, Tarantola also mentions a case from 1805 in Turin, where Francesco Rossi reported having experimentally transmitted rabies to dogs by inserting segments of the sciatic nerve from rabid cats into a fresh wound.

In the case of Portugal, when reading the inaugural dissertations, one notices that things were not done differently. Experiments with non-human animals were proposed within the field of human medicine in Portugal, too. For example, António José da Mota Campos Júnior, who defended his inaugural dissertation “Estudos recentes sobre o tétano” (Recent studies on tetanus)65 in 1892, made such proposals. Campos Júnior argued that: “it was experimentally demonstrated that the dog is not resistant to a small amount of pure culture. We know that the passage of a virus from one animal species to another sometimes attenuates, sometimes exacerbates its virulence: thus, rabies is attenuated.”66 Discussion of experiments is also included in the work of Júlio Artur Lopes Cardoso, who defended his dissertation “O Micróbio” (The microbe)67 in 1883. He drew the following conclusion: “a small portion of encephalic matter extracted from a rabid individual was introduced into the brain of a dog, and in less than 15 days, the animal developed the disease.”68 In these cases, dogs do not appear as vectors of rabies. On the contrary, they were literally inside the laboratories, in the fight against the disease. Thus, they ceased to be active in the transmission of rabies and became passive vectors, used in the process of developing prophylactic measures against the rabies virus through the medical research conducted by physicians at the Porto Medical-Surgical School.

While dogs appear in historiography in various contexts, in the case of the sources under discussion here, we find references to these animals both in a figurative sense and in human rituals.69 It is worth reiterating that the human species has coexisted with dogs for a very long time, and that the domestication of canines dates back over 5,000 years. More than mere objects at the service of humanity, dogs have contributed to shaping the decisions and procedures adopted by humans.70

It becomes evident that the coexistence between dogs and humans constitutes a significant “interspecies encounter” which, among other factors not addressed in this study, supports the argument that these non-humans contributed to the process of understanding disease transmission to humans. From this coexistence, viewed through the scientific lens adopted in this research, emerged the development of effective treatments for diseases affecting both animals and humans.71

The studies conducted at the Porto Medical-Surgical School reveal that Portuguese physicians were aware of the developments taking place abroad and were actively engaged in scientific research and in the renewal of medical thought across Europe. The analysis presented here has focused on the perception of animals as vectors of disease transmission, as well as tools in the development of experiments. Furthermore, as an analysis of the discourse reveals, the attention devoted by physicians to the roles of canines in the spread of the disease and the experimental procedures they used in the laboratory show clearly that these physicians considered the animals and their relationship to human health an important factor in the search for effective treatments to diseases as early as the nineteenth century.

The medical dissertations defended in Porto reveal that this aspect of human–non-human relationships captured the interest of physicians in the city’s medical school, and that, in harmony with findings in the study of the histories of zoonotic diseases so far, the presence of non-human animals was crucial to the development of various medical treatments, such as vaccines.72 The Pasteur Institute in Paris, one of the major points of reference in scientific research and innovation in the late nineteenth century for Portuguese physicians and physicians worldwide, based much of its laboratory experimentation on the investigation of relationships between humans and non-humans. These early experiments contributed to the development of a notion of health grounded in the interface between human beings, other animals, and the environment, which forms the foundation of the current initiative known as “One Health.”73

Raiva, Aerophobia, Hidrophobia, Tétanorábico…

The nomenclature used to define rabies in the nineteenth century was varied. This is a delicate aspect, as it relates to the different ways in which the same disease was referred to in historical sources, which makes data collection more challenging. Carlos Salgado de Andrade notes in his dissertation that the names by which this disease had been known are numerous and derive from the symptoms manifested in patients, such as intense thirst and a fear of water.74 Indeed rabies can manifest in several forms. Here, we refer specifically to human rabies in its furious form, characterized by hyperactivity, hallucinations, behavioral changes, hydrophobia (fear of water), and, at times, aerophobia (fear of air currents or fresh air).75

Given the nature of some of the symptoms associated with rabies, there were instances in which physicians interpreted them as episodes of madness. It is no coincidence that one of the common ways to refer to a dog afflicted with rabies is as a “mad dog.”

In the case of rabies in other animals, such as dogs, studies since the twentieth century have questioned the diagnosis of hydrophobia in these animals, given that dogs do not develop a fear of water. In 1939, Joaquim Augusto de Barros, in his doctoral thesis in veterinary medicine, asserted that “the rabid dog is not hydrophobic, that is, it does not have a fear of water.”76 In 1950, during a conference held at the Clube Fenianos Portuenses by the Portuguese League for Social Prophylaxis, under the theme “Rabies, a Disease Common to Humans and Animals: Methods of Control and Prophylaxis,” Manuel Lema Monteiro formulated the following argument: “the notion that the rabid animal does not drink and has a fear of water continues to be deeply rooted; and yet, the rabid dog does drink, it drinks frantically.”77

Figure 3. Nomenclature of rabies in the sources. Source: Inaugural Dissertations

Presented at the Porto Medical-Surgical School. Image created using AntConc.

The fight against rabies required care not only for human health but also for the health of other animals. It is important to highlight the varying symptoms of the same disease, which was given different names and presented differently in different organisms, as humans live in communities and as an integral parts of ecosystems. Thus, in order to remain healthy, humans must devote attention to the health of all of the members of these ecosystems.78 The observations made concerning similar symptoms in both humans and animals and the importance of providing care for the health of animals as well as humans may offer albeit modest evidence that among the newly graduated physicians of the EMCP, there was a degree of attention given to dogs, as seen in comments that also attest to the restoration of the animals’ health regarding other diseases. Carlos Alberto Salgado de Andrade, for instance, provided a detailed account of the dog’s behavior:

The animal avoids its owners, retreats to its usual resting place, to the corners of the house, beneath the furniture. It is called and responds, obeying slowly, as if reluctantly; instead of its characteristic joy, it approaches with its body hunched, fur bristled, head lowered, tucked between its paws and beneath its chest […] Appetite then ordinarily decreases, food is chewed with difficulty, and later rejected altogether, with swallowing becoming extremely painful.79

He also highlighted the estimated number of dogs cured through treatment, emphasizing that the number of dogs saved from rabies by this method80 was over 70 percent.81 José da Costa Silva Júnior, who presented “Breve estudo sobre a prophylaxia da raiva” (A brief study on rabies prophylaxis) in 1899, reported that among the 19 vaccinated dogs, not a single case of rabies was observed.82 Thus, the report is not limited to an exclusive discussion of the restoration of human health.

In the nineteenth century, up to the point covered by this study, the only decree or law issued by the Portuguese state concerning animal care is the aforementioned decree (Ministry of Public Works, Diário do Governo, No. 287, December 17, 1886), which approved the organizational plan for livestock services, ordering the monitoring of epizootic diseases. Nevertheless, even if comprehensive legislation was lacking at this point, physicians proposed guidelines on how to handle animals in order to control the transmission of rabies as part of narratives that reflected the medical profession’s role in the organization of society. Once again, Silva Júnior’s thesis can be cited as an example. He stated that, “in regions where the use of a muzzle is adopted, when an unmuzzled dog is seen on the streets, it immediately becomes suspect and should be seized by the competent authorities,” suggesting that the state should finds ways to introduce and enforce rules to control interaction between human and non-human animals.83

Human concern for and relationships with dogs have changed over time, but upon analyzing nineteenth-century discourses, we also find evidence of a more attentive and affectionate form of care, one that condemned the mistreatment of these animals. The following excerpt provides an example of this approach:

Poisoning of stray dogs. Unfortunately, our police make use of this method in the very place where the animals are found—a degrading practice, almost entirely abandoned elsewhere—because these animals, in the throes of a terrible agony, provoke public outrage, often leading to acts of revenge against the agents of this practice, which common sense and humanity alike condemn.84

We aim to argue that the inaugural dissertations defended at the Porto Medical-Surgical School reveal that nineteenth-century Portuguese medicine actively participated in the broader European scientific transformations of its time. The presence of dogs, whether as experimental subjects, disease vectors, or recipients of medical care, illustrates the complex and evolving understanding of human–animal relationships within medical thought. Far from being marginal references, these animals became essential to the development of experimental practices, the study of zoonotic diseases, and the emergence of preventive measures such as vaccination. Moreover, the diversity of terms used to describe rabies and its symptoms underscores both the diagnostic challenges of the period and the evolving nature of medical classification. Ultimately, these dissertations not only attest to Portugal’s engagement with contemporary scientific advances but also highlight an early awareness of the interconnectedness between human and animal health, an idea that foreshadows the modern concept of “One Health.”

Final Consideration

Rabies, that could be mistaken for an episode of madness, in the nineteenth century, was a disease that concerned Portuguese society, prompting action by political authorities, supported by medical and public health knowledge, to combat the threat. The role of human medicine, in conjunction with veterinary medicine, was one of the key elements that strengthened the response, and to this day, prophylaxis in non-human animals remains the most effective means of preventing rabies outbreaks. This study contributes to the analysis of the presence of canines in the dissertations by physicians in Porto in the nineteenth century, shedding some light on shifting understandings of the relationship between humans and non-humans in the past. It reflects a complex interaction among humans, dogs, the environment, and medicine, with implications for the factors that influenced public health within the Portuguese medical context.

The article provides an overview and contextualization of rabies research, with a focus on the presence of a non-human animal. The selected sources offer insights into the medical knowledge produced at the Porto Medical-Surgical School, which aligned with European medical thought during the period under study. Within these sources, focused primarily on human medicine, non-human animals, particularly dogs, are also present, demonstrating that the development of medical techniques and scientific observations relied on the presence of both human and non-human animals. Consequently, this underpins the thesis that the history of human medicine is not shaped by humans alone. The sources present early traces of what later, in the second half of the twentieth century, would come to represent the “One Health” approach, even before the formal articulation and institutionalization of the concept. The article therefore considers the history of medicine as a field, which can also be written as a history of “interspecies encounters,” where non-human animals, such as dogs, are present and participate, even if indirectly, in decision-making processes and the shaping of agendas aimed at addressing the challenges faced by human society.

Archival Sources

Biblioteca Pública Municipal do Porto [Municipal Library of Porto]

582.1939. Joaquim Augusto de Barros. “Diagnóstico da Raiva no cão.” Tese de doutoramento em Medicina Veterinária. Escola Superior de Medicina Veterinária, 1929.

3.1. 72.13. Monteiro M L. Liga Portuguesa de Profilaxia Social. “A raiva, doença comum ao homem e aos animais. Métodos de combate e profilaxia.” Conferência Realizada no Clube Fenianos Portuenses, em 4 de julho de 1950.

Bibliography

Abreu, Laurinda. Public Health and Social Reforms in Portugal (1780–1805). Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2016.

Almeida, Maria Antónia Pires de. “Pestana, Luís da Câmara.” Dicionário CIUHCT, Cientistas, Engenheiros e Médicos em Portugal. Accessed October 1, 2025. doi: 10.58277/LDJF6010

Andrade, Carlos Alberto Salgado. “Ligeira Contribuição para o Estudo da Raiva” [A small contribution to the study of Rabies in Portugal]. Inaugural diss., Escola Médico-Cirúrgica do Porto, 1901. https://hdl.handle.net/10216/16392. Accessed April 25, 2025.

Araújo, João Machado de. “Breve estudo sobre asepsia em cirurgia” [A brief study on surgical asepsis]. Inaugural diss., Escola Médico-Cirúrgica do Porto, 1875. Available at https://hdl.handle.net/10216/16304. Accessed April 25, 2025.

Blancou, Jean. “Rabies in Europe and the Mediterranean Basin: From Antiquity to the 19th Century.” In Historical Perspective of Rabies in Europe and the Mediterranean Basin: A Testament to Rabies by Dr. Arthur A. King, edited by Jean Barrat, and François-Xavier Meslin, 15–24. Paris: World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE), 2004.

Brown, Karen. Mad Dogs and Meerkats: A History of Resurgent Rabies in Southern Africa. Athens: Ohio University Press, 2011.

Campos Júnior, António José da Mota. “Estudos recentes sobre o tétano” [Recent studies on tetanus]. Inaugural diss., Escola Médico-Cirúrgica do Porto, 1892. Available at: https://hdl.handle.net/10216/16677. Accessed April 25, 2025.

Cardoso, Júlio Artur Lopes. “O Micróbio” [The microbe]. Inaugural diss., Escola Médico-Cirúrgica do Porto, 1883. Available at: https://hdl.handle.net/10216/16369. Accessed April 25, 2025.

Cruz, Manuel Pereira da. “Cemitérios” [Cemeteries]. Inaugural diss., Escola Médico-Cirúrgica do Porto, 1882. Available at: https://hdl.handle.net/10216/16457. Accessed April 25, 2025.

Decreto, 16 de Dezembro de 1886. Decreto (Ministério das Obras Publicas – Diário do governo n.° 287 de 17 de dezembro) approvando o plano da organisação dos serviços pecuarios. Available at: https://legislacaoregia.parlamento.pt/V/1/60/68/p916. Accessed April 25, 2025.

Dentinger, Rachel Mason. “The Parasitological Pursuit: Crossing Species and Disciplinary Boundaries with Calvin W. Schwabe and the Echinococcus Tapeworm, 1956–1975.” In Animals and the Shaping of Modern Medicine: Medicine and Biomedical Sciences in Modern History, edited by Abigail Woods, Michael Bressalier, Angela Cassidy, and Rachel Mason Dentinger, 161–91. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018.

Diário do Governo, 1925–11–16, n.º 247/1925, Série I de Ministério da Agricultura – Direcção Geral dos Serviços Pecuários, páginas 1452–1453. Available at: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/decreto/11242-1925-202604. Accessed April 25, 2025

Dias, José Pedro Sousa. “Da Cólera à Raiva” [From cholera to rabies]. In Assim na Terra como no Céu, Ciência, Religião e Estruturação do Pensamento Ocidental, edited by Clara Pinto Correia and José Pedro Sousa Dias, 435–49. Lisbon: Relógio D’Água, 2003.

Esteves, Alexandra and Sílvia Pinto. “Quando a morte espreita: as epidemias no Minho entre o século XIX e as primeiras duas décadas do século XX.” Revista M. Estudos sobre a morte, os mortos e o morrer 6, no. 11 (2021): 128–50. doi: 10.9789/2525-3050.2021.v6i11.128-150

Evans, B. R. and Frederick A. Leighton. “A history of One Health.” Revue scientifique et technique International Office of Epizootics 33, no. 2 (2014): 413–20. doi: 10.20506/rst.33.2.2298

Farah, Leila Marie, and Samantha L. Martin. Mobs and Microbes Global Perspectives on Market Halls, Civic Order and Public Health. Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2023.

Ferraz, Amélia Ricon. A Real Escola Médico-Cirúrgica do Porto [The Royal Medical-Surgical School of Porto]. Porto: Edições Centenário, 2013.

Fidalgo, Domingos Lopes. “Impressões de uma visita às cadêas do Aljube e Relação do Porto: higiene” [Impressions of a visit to the prisons of Aljube and Relação in Porto: Hygiene]. Inaugural diss, Escola Médico-Cirúrgica do Porto, 1889. Available at: https://hdl.handle.net/10216/17053. Accessed April 26, 2025.

Gomes, Inês. “Allies or Enemies? Dogs in the Streets of Lisbon in the Second Half of the Nineteenth Century.” In Science, Technology and Medicine in the Making of Lisbon, edited by Ana Simões and Maria Paula Diogo, 323–43. Leiden: Brill, 2022. doi: 10.1163/9789004513440_016

Howell, Philip. At Home and Astray: The Domestic Dog in Victorian Britain. London: University of Virginia Press, 2015.

Jones, Susan D. “Animal Diseases (Zoonotic).” In Encyclopedia of Plagues, edited by Joseph Byrne, 19–23. Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group, [2008].

Lance, Van Sittert. “Class and Canicide in Little Bess: The 1893 Port Elizabeth Rabies Epidemic.” South African Historical Journal 48 (2003): 207–34. doi: 10.1080/02582470308671932

Latour, Bruno. The Pasteurization of France. London: Harvard University Press, 1988.

Latour, Bruno. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Lucas, Patrícia Isabel Gomes. “Partidos e Política na Monarquia Constitucional: o caso do partido Regenerador (1851–1910)” [Parties and politics in the constitutional monarchy: The case of the Regenerator Party, 1851–1910]. PhD diss., Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas (FCSH), 2019. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10362/66164 Accessed September 25, 2025.

Marques, Alexandra Isabel Gomes. “O Instituto Bacteriológico Câmara Pestana: ciência médica e cuidados de saúde (1892–1930)” [The Câmara Pestana Bacteriological Institute: Medical science and healthcare, 1892–1930]. PhD thesis, Universidade de Évora, 2019. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10174/27791 Accessed April 26, 2025

Matouch, Oldřich. “Rabies in Poland, Czech Republic and Slovak Republic.” In Historical Perspective of Rabies in Europe and the Mediterranean Basin: A Testament to Rabies by Dr. Arthur A. King, edited by Jean Barrat and François-Xavier Meslin, 65–77. Paris: World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE), 2004.

Maxwell, Kenneth. Pombal, Paradox of the Enlightenment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

Moreira, Miguel Carlos. “A Raiva: (estudo historico, clinico e prophylactico)” [Rabies: historical, clinical, and prophylactic study]. Inaugural diss., Escola Médico-Cirúrgica do Porto, 1897. Available at: https://hdl.handle.net/10216/16510 Accessed 26 April, 2025.

Müller, Thomas, P. Demetriou, J. Moynagh, F. Cliquet, A. R. Fooks, Franz Josef Conraths, Thomas C. Mettenleiter, and Conrad Martin Freuling. “Rabies elimination in Europe – a success story.” Rabies Control – towards sustainable prevention at the source: Compendium of the OIE Global Conference on rabies control, 7–9 September 2011, 31–43. Incheon–Seoul, 2012.

Oliveira, António Augusto Chaves de. “Estudo sobre os diversos systemas de remoção das immundicias adoptados nas principaes cidades da Europa e sua applicação à cidade do Porto” [Study on the various systems of waste removal adopted in the principal cities of Europe and their application to the city of Porto]. Inaugural diss., Escola Médico-Cirúrgica do Porto, 1886. https://hdl.handle.net/10216/18204 Accessed 26 April 26, 2025.

Palma, Monique. “The influence of miasmatic theory on the construction of the Hospital Geral de Santo António in Porto in the nineteenth century.” História, Ciências, Saúde-Manguinhos 31, no. 11 (2024): 1–17. doi: 10.1590/s0104-59702024000100053.

Palma, Monique, João Alveirinho Dias, Joana Gaspar Freitas. “It’s Not Only the Sea: A History of Human Intervention in the Beach-Dune Ecosystem of Costa da Caparica (Portugal).” Journal of Integrated Coastal Zone Management 21, no. 4 (2021): 227–47.

Palma, Monique. Cirurgiões, práticas e saberes cirúrgicos na América portuguesa no século XVIII. Espanha: Fundacion Academia Europea e Iberoamericana de Yuste, 2021.

Pearson, Chris. “Dogs, history, and agency.” History and Theory 52, no. 4 (2013): 128–45.

Pemberton, Neil and Michael Worboys. Mad Dogs and Englishmen: Rabies in Britain 1830–2000. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007.

Pita, João Rui. Farmácia, Medicina e Saúde Pública em Portugal (1772–1836) [Pharmacy, medicine, and public health in Portugal, 1772–1836]. Coimbra: Livraria Minerva Editora, 1996.

Pitt Sarah J. and Alan Gunn. “The One Health Concept.” British Journal of Biomedical Science 81 (2024): 1–15. doi: 10.3389/bjbs.2024.12366

Porter, Roy. The Greatest Benefit to Mankind: A Medical History of Humanity from Antiquity to the Present. London: Fontana Press, 1999.

Silva Júnior, José Costa. “Breve estudo sobre a prophylaxia da raiva” [A brief study on rabies prophylaxis]. Inaugural diss., Escola Médico-Cirúrgica do Porto, 1889. Available at: https://hdl.handle.net/10216/16926. Accessed April 26 , 2025.

Snowden, Frank M. Epidemics and Society: From the Black Death to the Present. New Haven and London: Yale University of Press, 2020.

Sousa, Francisco José. “Algumas palavras sobre a opotherapia: tratamento de certas doenças por extractos d’orgãos animais” [Some remarks on opotherapy: the treatment of certain diseases using extracts from animal organs]. Inaugural diss., Escola Médico-Cirúrgica do Porto, 1899. Available at: https://hdl.handle.net/10216/17222. Accessed 26 April 26, 2025.

Tarantola, Arnaud. “Four Thousand Years of Concepts Relating to Rabies in Animals and Humans, Its Prevention and Its Cure.” Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 2, no. 5 (2017): 2–21. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed2020005.

Teigen, Philip. M. “Legislating Fear and the Public Health in Gilded Age Massachusetts.” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 62 (2007): 141–70.

Tsing, Anna. The Mushroom at the End of the World. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2015.

Van Seventer Jean Maguire, Natasha S. Hochberg. “Principles of Infectious Diseases: Transmission, Diagnosis, Prevention, and Control.” International Encyclopedia of Public Health (2017): 22–39. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-803678-5.00516-6

Vieira, Ismael. C. “As teses inaugurais da Escola Médico-cirúrgica do Porto (1827–1910): uma fonte histórica para a reconstrução do saber médico.” Revista Cultura Espaço & Memória, CEM 3 (2018): 251–60.

Woods, Abigail, Michael M. Bresalier, Angela Cassidy and Rachel Mason Dentinger. Animals and the Shaping of Modern Medicine and Biomedical Sciences in Modern History. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-64337-3

WHO. Global Framework to Eliminate Human Rabies Transmitted by Dogs by 2030 (2016). https://www.woah.org/fileadmin/Home/eng/Media_Center/docs/Zero_by_30_FINAL_online_version.pdf Accessed April 26, 2025.

WHO. 28 September is World Rabies Day. https://www.who.int/campaigns/world-rabies-day Accessed April 26, 2025.

WHO. Global burden of dog-transmitted human rabies. https://www.who.int/teams/control-of-neglected-tropical-diseases/rabies/epidemiology-and-burden Accessed April 26, 2025.

WHO. Neglected tropical diseases. https://www.who.int/health-topics/neglected-tropical-diseases#tab=tab_1 Accessed September 22, 2025.

-

1 Moreira, “A Raiva,” 57.

-

2 This article focuses on the presence of dogs; however, the research adopts a broader scope, aimed at identifying and understanding the various non-human animals mentioned in medical writings, particularly in the nineteenth century.

-

3 Palma, “The influence of miasmatic theory.”

-

4 WHO, “Global burden of dog-transmitted human rabies”; Woods et al. Animals and the Shaping of Modern Medicine.

-

5 We still need more studies on rabies to clarify the calamity that occurred in Porto at the time. So far, it is known that, in Portugal, the number of deaths caused by rabies in hospital sources is not precise. In any case, as we will see later in this study, specialized centers were established in the country for the development of the anti-rabies serum. Marques, “O Instituto Bacteriológico Câmara Pestana,” 1–30.

-

6 Abreu, Public Health and Social Reforms in Portugal.

-

7 Andrade, “Ligeira contribuição.”

-

8 An infectious and contagious disease is a pathology caused by biological agents (such as viruses, bacteria, fungi, and parasites) that can be transmitted from one person or animal to another. Cf. van Seventer and Hochberg, Principles of Infectious Diseases: Transmission, Diagnosis, Prevention, and Control, 22–39.

-

9 Andrade, “Ligeira contribuição.”

-

10 Ibid., 2.

-

11 Pitt and Gunn, The One Health Concept, 1–2.

-

12 Jones, “Animal Diseases (Zoonotic),” 19.

-

13 Pitt and Gunn, The One Health Concept, 1–2.

-

14 Woods et al. Animals and the Shaping of Modern Medicine, 163.

-

15 Andrade, “Ligeira contribuição,” 11.

-

16 Evans and Leighton, “A history of One Health,” 413–20; Farah and Martin, Mobs and Microbes.

-

17 Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World.

-

18 The World Health Organization has issued the following statement: “Neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) are a diverse group of conditions caused by a variety of pathogens (including viruses, bacteria, parasites, fungi and toxins) and associated with devastating health, social, and economic consequences. NTDs are mainly prevalent among impoverished communities in tropical areas, although some have a much larger geographical distribution. It is estimated that NTDs affect more than 1 billion people, while the number of people requiring NTD interventions (both preventive and curative) is 1.495 billion. The epidemiology of NTDs is complex and often related to environmental conditions. Many of them are vector-borne, have animal reservoirs and are associated with complex life cycles. All these factors make their public-health control challenging.” For more information see: WHO, Neglected tropical diseases.

-

19 Although some concerns remain regarding rabies in the wild. Cf. Blancou, “Rabies in Europe”; Matouch, “Rabies in Poland, Czech Republic and Slovak Republic.”

-

20 Müller et al., “Rabies elimination in Europe,” 31.

-

21 Diário do Governo, 1925–11–16, n.º 247/1925, Série I de, Ministério da Agricultura – Direcção Geral dos Serviços Pecuários, 1452–1453.

-

22 Müller et al., “Rabies elimination in Europe,” 31.

-

23 Bruno Latour developed the concept of Actor-Network Theory (ANT), which encompasses various processes for analyzing interspecies relationships. He proposed a framework for examining sources and the agents involved within them. While I recognize and value Latour’s contribution to the discussion of non-human agency, my approach does not adhere to his specific model of ANT analysis. For further discussion on ANT, see Latour, The Pasteurization of France; Latour, Reassembling the Social.

-

24 Pita, Farmácia, Medicina e Saúde Pública; Porter, The Greatest Benefit to Mankind.

-

25 Esteves and Pinto, “Quando a morte espreita.”

-

26 Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo (1699–1782), the Marquis of Pombal, served as ambassador of King João V to the English and Austrian courts. During the reign of King José I, he was appointed Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs and War (1750). Later, King José I, entrusted him with the governance of the kingdom, appointing him Prime Minister. The monarch acknowledged his merit for the work carried out in the reconstruction of the lower part of Lisbon after the earthquake of 1755. Among the most significant measures implemented by Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo were reforms in education, public administration, finance, and the military system. Maxwell, Pombal, Paradox of the Enlightenment.

-

27 Palma, Cirurgiões, práticas e saberes, 27–44.

-

28 Porter, The Greatest Benefit to Mankind, 303.

-

29 Woods et al., Animals and the Shaping of Modern Medicine, 258.

-

30 Gomes, “Allies or Enemies? Dogs in the Streets of Lisbon.”

-

31 Lance, “Class and Canicide in Little Bess”; Brown, Mad Dogs and Meerkats.

-

32 Teigen, “Legislating Fear.”

-

33 Pemberton and Worboys, Mad Dogs and Englishmen; Howell, At Home and Astray.

-

34 Woods et al. Animals and the Shaping of Modern Medicine, 258–59.

-

35 From a historiographical perspective, certain details and episodes stand out as particularly significant. An epizootic of canine rabies was documented in Hungary in 1586, with another recorded in 1722. In 1711, Gensel reported a severe rabies outbreak “among wild animals” in the same region, which was subsequently transmitted to both dogs and humans. In November 1829, a wolf attacked eleven individuals in Máramaros County in Transylvania (Judeţul Maramureş, today in Romania), four of whom later died from rabies. A similarly alarming case occurred in 1766 near Warsaw, where a rabid wolf bit 23 people, all of whom succumbed to the disease. Matouch, “Rabies in Poland, Czech Republic and Slovak Republic,” 22.

-

36 WHO, 28 September is World Rabies Day.

-

37 Marques, “O Instituto Bacteriológico Câmara Pestana.”

-

38 Luís da Câmara Pestana (1863–1899) stands out as one of the key figures in the introduction and consolidation of bacteriology in Portugal at the end of the nineteenth century. A graduate of the Lisbon Medical-Surgical School, Câmara Pestana was among the first Portuguese physicians to systematically apply the experimental methods derived from the discoveries of Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch, contributing to the modernization of medical and laboratory practices in the country. Cf. Almeida, Dicionário CIUHCT.

-

39 Marques, “O Instituto Bacteriológico Câmara Pestana”; Maio, Breve História da Raiva em Portugal.

-

40 Andrade, “Ligeira contribuição,” 71.

-

41 Esteves and Pinto, “Quando a morte espreita,” 147.

-

42 Maio, Breve História da Raiva em Portugal, 59.

-

43 Esteves and Pinto, “Quando a morte espreita,” 146.

-

44 Maio, Breve História da Raiva em Portugal, 4–30.

-

45 Decreto, 16 de Dezembro de 1886. Decreto (Ministério das Obras Publicas – Diário do governo n.° 287 de 17 de dezembro) approvando o plano da organisação dos serviços pecuários.

-

46 Dias, “Da Cólera à Raiva,” 435–49.

-

47 Ibid.

-

48 The Chamber of Deputies in Portugal at the end of the nineteenth century was the country’s representative legislative body, equivalent to the present-day Assembly of the Republic.

-

49 Marques, “O Instituto Bacteriológico Câmara Pestana,” 35.

-

50 The Regenerator Party (1851–1919) was one of the main political forces of the rotativism system during the period of the Portuguese constitutional monarchy, alternating in power with the Progressive Party (1876–1910). Emerging during the Regeneration period (1851–1868), it consolidated itself as a conservative-oriented party, in opposition to the more liberal-leaning Progressive Party. Lucas, Partidos e política na Monarquia, 19–45.

-

51 Ibid.

-

52 Palma et al., “It’s Not Only the Sea”; Palma, “The influence of miasmatic theory.”

-

53 Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World; Palma, “The influence of miasmatic theory.”

-

54 In the field of medicine, students were required to produce a dissertation at the end of their studies, as stipulated in Article 154 of the Decree of April 23, 1840 (D. Maria II, 1840, p. 119), enacted during the second reign of Queen Maria II (1826–1827, 1834–1853). The decree sought to regulate the medical-surgical schools of Lisbon and Porto. This requirement, however, was not well received by medical students, as evidenced in the prefaces to many dissertations, where authors often stated that their work merely fulfilled an academic obligation. Despite this, these dissertations constitute an important source for the history of medicine, reflecting a period of profound transformation in medical thought and practice. Palma, “The influence of miasmatic theory.”

-

55 Ferraz, A Real Escola Médico-Cirúrgica do Porto.

-

56 The Open Repository of the University of Porto can be accessed at the following link: https://repositorio-aberto.up.pt Accessed April 26, 2025.

-

57 Palma, “The influence of miasmatic theory”; Palma, “‘Inconstancia do clima’”; Vieira, “As teses inaugurais da Escola Médico-cirúrgica do Porto.”

-

58 Palma, “The influence of miasmatic theory.”

-

59 Araújo, “Breve estudo sobre asepsia.”

-

60 Sousa, “Algumas palavras.”

-

61 Oliviera, Estudo sobre os diversos systemas.

-

62 Moreira, “A Raiva.”

-

63 Silva Júnior, “Breve estudo.”

-

64 Tarantola, “Four Thousand Years of Concepts,” 5.

-

65 Campos Júnior, “Estudos recentes.”

-

66 Ibid., 49.

-

67 Cardoso, “O Microbio.”

-

68 Ibid., xxx.

-

69 Fidalgo, “Impressões de uma visita”; Cruz, “Cemitérios.”

-

70 Pearson, “Dogs, History, and Agency.”

-

71 Dentinger, “The Parasitological Pursuit”; Andrade, “Ligeira contribuição.”

-

72 Snowden, Epidemics and Society, 83–96.

-

73 Woods et al. Animals and the Shaping of Modern Medicine, 1–20.

-

74 Andrade, “Ligeira contribuição.”

-

75 WHO, Global Framework to Eliminate Human Rabies.

-

76 Biblioteca Municipal do Porto. 582.1939. Joaquim Augusto de Barros. “Diagnóstico da Raiva no cão.” Tese de doutoramento em Medicina Veterinária. Escola Superior de Medicina Veterinária, 1929.

-

77 Biblioteca Pública Municipal do Porto. 3.1. 72.13. Monteiro M L. Liga Portuguesa de Profilaxia Social. “A raiva, doença comum ao homem e aos animais. Métodos de combate e profilaxia.” Conferência Realizada no Clube Fenianos Portuenses, em 4 de julho de 1950.

-

78 Woods et al., Animals and the Shaping of Modern Medicine, 1–20.

-

79 Andrade, “Ligeira contribuição,” 14.

-

80 For more, see: Andrade, “Ligeira contribuição,” 82.

-

81 Andrade, “Ligeira contribuição,” 82.

-

82 Silva Júnior, “Breve estudo,” 46.

-

83 Ibid., 87.

-

84 Ibid., 85.