Centralizing Custody and Curing by Chance:  Early Austrian Madhouses under Medical Supervision and State Constraint, c. 1780–1830

Early Austrian Madhouses under Medical Supervision and State Constraint, c. 1780–1830

Carlos Watzka

Sigmund Freud Private University, Vienna

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Hungarian Historical Review Volume 14 Issue 4 (2025): 493-536 DOI 10.38145/2025.4.493

This article offers an overview of the early development of madhouses as an institutional framework for the custody and treatment of mentally ill persons, from the initial phase of comprehensive governmental health politics in Austria (the peak of the Enlightenment movement in the region in the late eighteenth century) until 1830, when a second phase, which had begun in 1815 and which bore witness, again, to the establishment of asylums for people suffering from mental disorders, came to an end with the foundation of an asylum in the city of Hall in Tyrol. The article outlines the establishment of such institutions for the accommodation, detention, and, partially, treatment of people seen as insane in the Austrian Hereditary Lands as a political and societal attempt to react to a rising number of individuals who were perceived as suffering from serious mental problems but whose families and communities either did not feel obliged to provide care for them or were simply not capable of treating them anymore in their respective localities. The article points out, as has been noted in the secondary literature, that all early madhouses in Vienna, Linz, Graz, and Salzburg operated primarily as institutions for the internment of persons perceived as mentally ill and posing a threat to themselves and others. The physicians involved intended to implement therapeutical activities, but this was only rarely possible due to a lack of financial resources, accommodation space, and asylum staff.

Keywords: madhouse, psychiatry, Austria, Josephinism, early nineteenth century, social history

Introduction: The Scope and State of Research

In the discussion below, I offer an overview of the early institutional history of madness in Austria in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.1 Remarkably, one does not find, in the secondary literature, any real comprehensive or systematic accounts of the historical development of discourses and practices dealing with people deemed insane in Austria before 1900.2 Hence, this article presents a still provisional overview of the state of research regarding aspects fundamental to asocial-historical analysis of the issue. It focuses on the following questions: what type of institutions were there to provide care for those deemed mentally unfit? When and where were they established? What resources and treatments were used, in what manner, and with what outcomes?

Regarding the history of the mentally ill and the ways in which they were treated in even earlier periods, it should be noted here that peculiar discourses and practices had been present in Austria (and in most regions of Western and Central Europe) since the Middle Ages, with an increasing number of sources from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries onwards,3 relating to academic as well as clerical and popular medicine.4

Nonetheless, within the Habsburg Monarchy, it was not until the last decades of the eighteenth century that social institutions were established with the specific public mandate to provide custody and/or care for people who were regarded as mentally ill and whose circumstances were perceived as a social problem. The appearance of the “madman”5 as a social role and prominent cultural figure was connected to broader sociocultural changes. Since the publication of the works of Michel Foucault, Erving Goffman, Klaus Dörner, and several other prominent representatives of “antipsychiatry” in the 1960s and 1970s,6 the historical research community, too, has devoted considerable attention to the topic of insanity. From the 1980s onwards, the history of the institutionalization of mental health care began to be written by professional historians who adopted clearly critical perspectives, inspired in part by insights from social and cultural history.7 They all identified an increase in political and social demands for the control of people suffering from mental disorders in early modern Europe. For the most part, this transformation directly affected not only the mad themselves, but also those in their immediate surroundings. This process was largely ambiguous and in many cases devastatingly negative in terms of both the quality of the life for patients in institutions and even from the quantitative perspective of their life expectancies.8 On the other hand, increasingly intense material and intellectual efforts were made to cure the mentally disturbed in this period, in part because of the influence of Enlightenment ideas concerning the curability of madness, which formed something of a widespread ideal and mindset among the middle and upper classes.9

The pace of this process varied across Europe, and it clearly depended in part on the regional tendencies in technological progress, urbanization, and industrialization.10 These processes led to an increasing number of individuals not living within the traditionally narrowly woven networks of family and neighborhood communities anymore. These communities, which of course should hardly be idealized, usually played important roles in addressing interpersonal conflicts, thus restricting the demand for permanent institutional accommodation mainly to cases of perceived need for intensive care or custody, which would have overstrained the resources of the local community.11

The time span under discussion in this article stretches from the late eighteenth century to 1830, the year in which the first phase of the institutionalization process in Austria came to a temporary end with the opening of an Irrenheilanstalt in the town of Hall in Tyrol. Later, from the 1850s and 1860s, several other projects were launched to create new spaces for a rapidly expanding “population” of inmates. The spatial scope was limited to the Austrian Hereditary Lands, which had a majority German-speaking population and a direct nexus to the Austrian core land. Therefore, neither the Bohemian nor the Polish crown lands, the Kingdom of Hungary, Vorderösterreich (Outer Austria), the Litoral, or Carniola are dealt with here. It is worth noting that the secondary literature on early psychiatry in the area under study here (roughly, the territory of modern-day Austria, though also including parts of South Tyrol and Lower Styria, and excluding Burgenland, which was part of Hungary until 1920–21) is quite heterogenous. Even in the case of Vienna, which was the imperial capital and the political, economic, and cultural center of the Habsburg Monarchy (and was considered the “vanguard of progress” in many fields and had the most comprehensive public infrastructure), until recently, no extensive or thorough scholarly studies have been published on the early stages of psychiatry.12 Until recently, very little had been written even on the “Narrenturm” (Tower of Fools), which was founded in 1784 and garnered enormous notoriety as an irritatingly noticeable symbol of the beginnings of psychiatry in Austria (it now houses the anatomical-pathological collection of the Naturhistorisches Museum of Vienna). The regrettably fragmented state of the secondary literature on the topic has now begun to change due to new, insightful publications. Above all, in 2023, Viennese physician and writer Daniel Vitecek published the first (!) comprehensive scholarly monograph on the medical and social history of the Narrenturm and the beginnings of psychiatry in Lower Austria, including the peculiar institution for mental patients regarded as incurable in Ybbs. Vitecek presents a vast array of valuable earlier findings, hitherto scattered in various remote contributions, and also several entirely new insights based upon sources analyzed from this perspective for the first time.13

Remarkably, from the perspective of the institutionalization of mental health care in the nineteenth century, Tyrol is the Austrian region that has been the most thoroughly studied, even though this process began in Tyrol later than in other regions of the monarchy. The research group dedicated to the social history of medicine and medical humanities at the University of Innsbruck has produced remarkable results in this field since the 1990s, with contributions by Elisabeth Dietrich-Daum, Maria Heidegger, Michaela Ralser, and others.14 Heidegger in particular has published numerous insightful contributions regarding Tyrolean psychiatry in the mid-nineteenth century from several perspectives. In addition to social and patient history, she has focused on gender history, the history of emotions, and body history.15 For Salzburg, the first historical analysis by Harald Waitzbauer was published in 1998, and recently, a further overview, examining additional archival sources, was authored by Theresa Lumetzberger. Both works deal with the period before the mid-nineteenth century, though the focus is on later periods, as is the case in Elisabeth Telsnig’s study on artistic work by psychiatric inmates in the region.16 For other parts of Austria, until now, there have been no studies comparable in extent or chronological scope on the early stages of psychiatry, neither for the more populous crownlands of Upper Austria and Styria nor for Carinthia.17 For Upper Austria, some research on the initial phases of housing for the mentally ill since the 1780s was done in 1970s and 1980s by Konrad Plass, Gustav Hoffmann, and others, but no additional studies have been undertaken.18 Regarding the history of psychiatry in Styria, particularly the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries are moderately well-researched now, but for the period before the mid-nineteenth century, there is much research still to be done. Overviews were given by Carlos Watzka and Norbert Weiss.19 In the case of Carinthia, the nineteenth-century history of the asylum founded in Klagenfurt in 1822 has largely been overlooked, despite some efforts by Paul Posch, Karl Frick, Lisa Künstl, and Thomas Platz.20

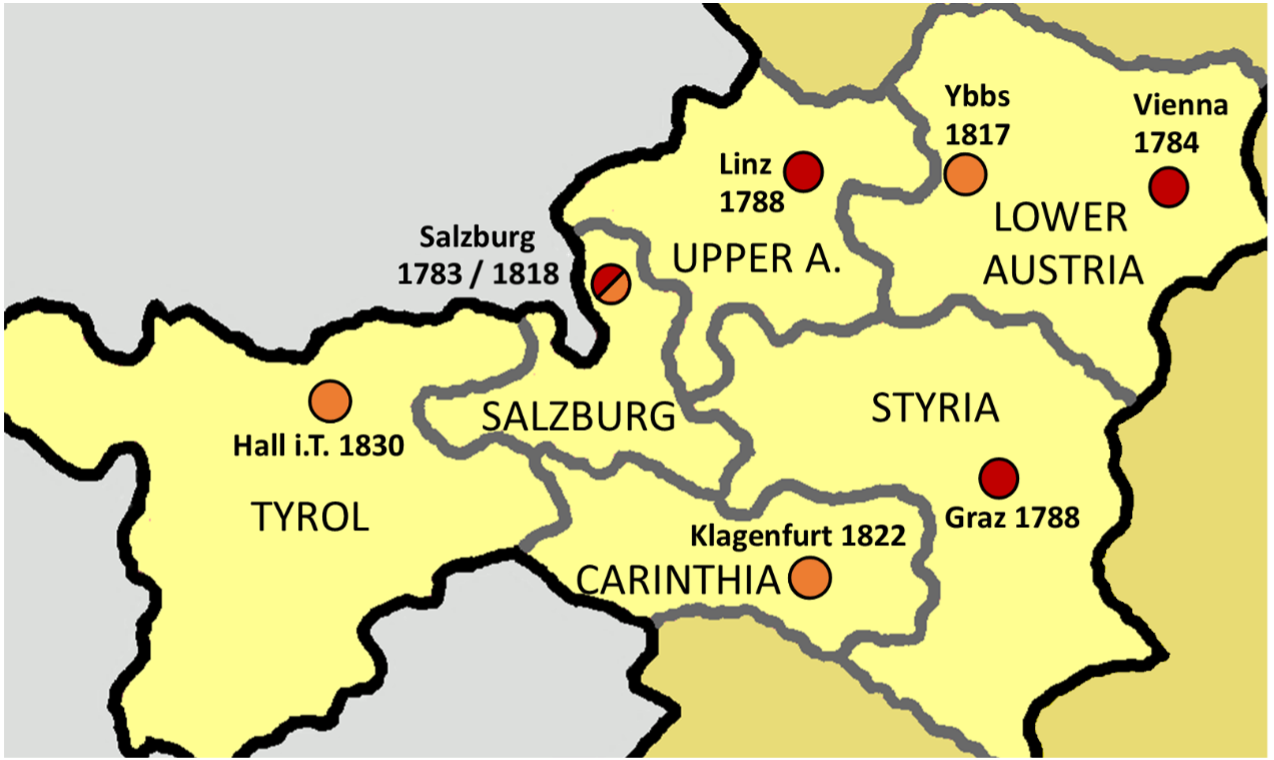

Figure 1. Early public madhouses within the area of contemporary Austria, 1780 to 1830

(Sketch map by C. Watzka, based on a template available at Wikimedia commons)

In the discussion below, I examine the development of public institutional structures for the custodial care and, eventually, the cure of the mad in the Austrian Hereditary Lands between the 1780s and 1830, drawing mainly on the secondary literature and printed sources.21 I pay attention particularly to fundamental aspects, such as buildings, staff, patients, and their living conditions, as well as the therapies eventually provided for them. The broader context of the cultural and social history of the Habsburg Monarchy in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, including its politics regarding poor relief and the healthcare system in general, is dealt with only selectively here, when connections of processes in these wider fields with concrete institutional developments in mental health care are highlighted.22

The Tower of Fools (Narrenturm) in Vienna

Compared to Western Europe, from the perspective of early efforts to establish a specialized structure for the internment and, eventually, treatment of the mad, Austria was a latecomer, even though the opposite is sometimes asserted in older literature and on some popular websites even today. The beginnings of larger, specialized structures for the accommodation of the insane date back to the fifteenth century in Spain and to the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in Italy, France, England, Holland, Germany, and Poland.23 In Austria, however, until about the mid-eighteenth century the task of providing custody for insane persons was largely left to a non-centralized structure of small multifunctional hospitals, often owned and run by communities or religious orders. Additionally, some state-run poorhouses also began to accommodate mad people as an additional task. This situation, albeit probably advantageous at least for some of the affected individuals, was seen as insufficient by the central authorities, especially in light of permanently growing public demands. Yet it was not until the government of Emperor Joseph II from 1780 to 1790 that any large-scale establishment of state institutions for public health care in general was implemented, and this then took place in the context of a systematic effort to strengthen the agency of the central government and, in turn, to cut back the political and social power of the Catholic Church and other stakeholders, such as the already quite insignificant traditional, regionally based nobility. With such regulations, which bore strong affinities with other projects for progress, Joseph II and the enlightened official nobility around him put into practice the concept of “medizinische Policey,” or medical police, developed by academic physicians of the time. Johann Peter Frank (1745–1821) of south German origin, the most prominent and productive of them,24 was recruited as a medical professor first for Austrian Lombardy in 1785 and then took over the Viennese general hospital in 1795. The foundation of the latter in 1784 was the work of his Vienna-born predecessor, Joseph von Quarin (1733–1814), who had served as personal physician to Maria Theresia and Joseph II.25

In 1781, Joseph II focused his attention on efforts to provide relief and healthcare for the poor. He himself authored the so-called “Directiv-Regeln,” the rules for the future establishment of hospitals and care institutions. These rules formulated the principle of internal separation between the various kinds of needy persons, the impact of which lasts until today. The intention was to draw a clear distinction between children (foundlings and orphans) and adults and to provide separate accommodations for them. Among the latter, it distinguished between pregnant women in need of maternal care, people who were “merely” poor but healthy, poor individuals with acute but treatable diseases, and people who were poor and chronically ill or disabled.26 This categorization, which reflects the emphasis among the so-called enlightened on classifications (particularly of matters regarded as problematic, as discussed by Foucault),27 was enriched by a peculiar further category of ill persons, namely those not regarded as suitable for treatment within the general hospital. This classification applied to individuals who for some reason “cause damage or disgust” and included Wahnwitzige (maniacs), people purportedly suffering from venereal diseases, and those with visible signs of illness or damage to the body (Krebse or cancers). All of them, according to the emperor himself, had “to be removed from general society and from the eyes of humans.”28

The Viennese Narrenturm, which was established in 1784 as the first purpose-built madhouse in the Habsburg Monarchy, was part of these coordinated efforts to create a state-run public health care system for the urban population of the capital, which had roughly doubled over the course of only 80 years, from more than 120,000 around 1700 to approximately 250,000 in the 1780s.29 The Narrenturm was situated within the area of the new general hospital in the Alsergrund suburb (today the ninth district of Vienna). For the building itself, the former Großarmenhaus (Large Poorhouse) was used. This edifice had been established in the 1690s and had been home to more than 1,600 inmates in 1781, when it was dissolved.30

The foundation of the Viennese Narrenturm or Tollhaus was a personal project for Emperor Joseph II, who spent a considerable amount of money from his personal funds and dedicated significant efforts to its creation, thus centralizing the detention of the mad hitherto accommodated within various smaller structures. In quantitative terms, the wing for mad inmates at the large civic hospital in the Saint Marx suburb of Vienna (today the third district of Vienna) was probably the largest source for transfers to the newly erected Narrenturm. The hospital had offered space for 300 to 500 persons altogether in the mid- and late-eighteenth century, including space dedicated for the internment (and eventually treatment) of about 30 people perceived as mad. In reality, it accommodated up to nearly 80 persons of allegedly “corrupted” mind in the 1760s and 1770s, as Sarah Pichlkastern has shown in her extensive research on the Viennese Civic Hospital and its various sites.31

Prior to its opening, other inmates who came to be lodged in the Narrenturm had been accommodated in institutions such as civic poorhouses scattered across the city and its surroundings. These institutions held more than 2,600 inmates already in 1766, of whom at that date 128 (ca. 5 percent) were considered “Hinfallende, Habnärrische, Blödsinnige” (epileptics, half-fools, or stupid), as Daniel Vitecek’s research has demonstrated, drawing on the Wienerische Diarium, a journal which reported on the issue. Patients were also transferred to the Narrenturm from the Viennese Spanish Hospital (also called the Trinity Hospital) in the Alsergrund suburb and the monastic hospital of the Barmherzige Brüder (Order of Saint John of God) in the Leopoldstadt suburb (today the second district of Vienna),32 which mainly treated somatic diseases but also offered accommodation and treatment for the mentally ill in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.33 That hospital was left open even during the Josephinist cloister dissolutions because of its acknowledged practical value, but with regards to accommodation for the mentally ill, it was limited by imperial order to the task of providing care exclusively for insane clergymen.34

By founding the Narrenturm, Joseph II and his government avowedly intended to ameliorate the living conditions and, particularly, chances of recovery for the insane. Thus, this initiative resembled the founding of the general hospital in Vienna, which was established to improve the circumstances and living conditions of those suffering from some bodily illness. Nonetheless, the emperor himself was not free of stereotypical and prejudiced convictions regarding illness and insanity, even by contemporary standards. In particular, he obviously held the traditional belief that, were a pregnant woman to behold something disgusting or horrifying, this might have dire consequences for the health and sanity of her unborn child. “Objects or humans” that were deemed a horrific sight were therefore to be isolated and kept away from the public eye as a matter of public health.35

Unfortunately, the sources reveal only broad outlines concerning Joseph II’s personal ideas on the needs and legitimate claims of the mentally ill. But the issue of providing accommodation and care for the insane was clearly a target of the emperors’ pronounced habit of thriftiness, as he personally gave the order, still in 1784, to provide “only a diet of four Kreuzer per day” “for the mad,” instead of the seven Kreuzer given as the amount that would cover the average expenses for “ordinary” patients at the Viennese General Hospital.36 Perhaps the belief in a general “lack of judgement” among the mad, which was quite common among in enlightened thought, contributed to the emperor’s conclusion that it would not “pay off” to provide expenses beyond the sheer minimum for madmen, as differences between higher or lower quality of food, clothing, or furniture would not be noticed by them, and shortcomings would not be have the same negative health effects as they would for “normal” persons. Vitecek summarizes the sobering effect of Joseph’s II personal interest in designing the first Austrian mental asylum: “the scarcest equipment and scarcest staff” were allocated to the Narrenturm, compared with the other institutions founded by the emperor.37

This, of course, had dire consequences for the inmates of the new institution. In contrast to at least some of the hospitals where these people had been accommodated before, in the Narrenturm, all approximately 250 inmates were indiscriminately prohibited from taking walks outside the building. Only two small and dark inner courtyards were set aside for this purpose (see Fig. 2). This order was kept even after the death of Joseph II in 1790. Eventually, during the principalship of Johann Peter Frank, in 1796, two small gardens, surrounded by a high wall, were installed, offering the inmates somewhat better conditions and an opportunity to enjoy sunlight and fresh air.38

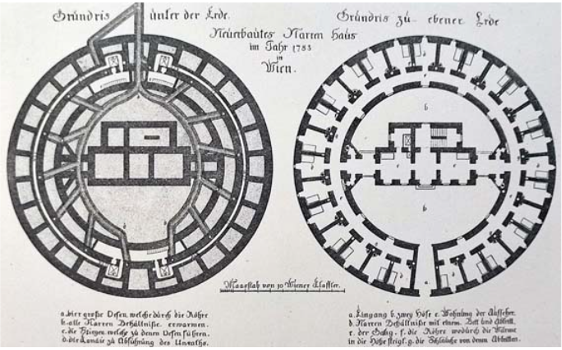

Figure 2. The Narrenturm in Vienna: the blueprint of the basement and ground floor,

displaying the cell structure, the building for the staff, the courtyards, and pipes for heating and the removal of waste.

(Copper etching, Vienna 1783. Image in the public domain)

There obviously was a strong drive behind the Josephinian government to segregate the insane from a society believed to be in a state of becoming increasingly healthy (including with reference to its mental wellbeing) due to a virtually all-embracing medical police and the broad healthcare measures launched in the monarchy. Notions concerning the possible transmissibility of madness by infection, even if they were not widely believed, may have played a certain role in this practice of exclusion as well. Thus, in enlightened late eighteenth-century Vienna, official approaches to care for the insane clearly put the idea of custodialism at the forefront, and therapeutical pursuits were a distant second. This was expressed openly by the inscription on the Narrenturm’s entrance since about 1790, by order of Leopold II, the successor to Joseph II: Custodiae mente captorum, or “to provide custody of the insane.”39 In this regard, the Austrian version of enlightened biopolitics appears to have been a quite defensive and conservative one, even during the reign of Joseph II, which was allegedly the peak of progressive tendencies.40

Figure 3. Depiction of the Narrenturm in Vienna, Painting by Franz Gerasch

(mid-nineteenth century)

(CC – Belvedere Online Collection:

https://sammlung.belvedere.at/objects/12044/das-alte-irrenhaus-in-wien-narrenturm-kaiser-josephguge)

The menacing exterior of the Viennese madhouse (see Fig. 3), which was described as “a terrible prison far from all human society” as early as 1793 by an anonymous visitor, corresponds with its distinctive inner structure. In other words, this interior is a seemingly endless circular sequencing of small cells, which were used to isolate inmates from one another, though they tended to confuse everybody residing in the building (as one can experience even today by taking a personal visit). This structure was designed at the order of Joseph II to contain either only one or two detainees per cell, who, from the outset, were to be locked up in their cells with the use of iron manacles and chains if considered dangerous, as most of them were.41 The cells on each floor form an outer ring structure, easily supervised by the wardens from the circular gangway making up the inner ring of the building, connected by the central wing, accessible only to the staff (see Fig. 2). Cells were furnished in a manner designed to reduce the need for direct interaction between staff and inmates to a minimum, with slightly angled floors to allow excrement to run on its own into a drainage system. A central heating system was used to avoid any need for stoves or furnaces near the cells. Iron rings were installed in the walls to make it possible to bind inmates with chains. Heavy double doors with locks were used, along with barred windows, to prevent attempts to escape.42 Quite clearly, at least for the decision-makers involved in the founding of this asylum, there must have been a considerable fear of the people who were put into custody in the edifice.

Yet, the whole building, which was erected in less than two years (1783–1784), seems to represent, in addition to its practical function as a madhouse, some of Joseph II’s very distinctive ideas. The emperor hired acknowledged master builder Josef Gerl (1734–1789) to implement his vision. Even apart from the somewhat daring assumption that the installation of a lightning rod on the roof of the building (it is perhaps worth noting that the Narrenturm was one of the first buildings in Vienna to receive one) had been part of a secretly planned device for experimental electrotherapy,43 the basic architectural features of the madhouse seemed peculiar to most observers from its foundation. This included the overall tower-like shape, which inspired its non-official name, “Tower of Fools” (instead of house). This designation quickly spread in popular discourse, as did the nickname the “Emperor’s Guglhupf,” which was attached to it later. The outstanding 2023 monograph on the Narrenturm by Daniel Vitecek underpins the assertion that this and other stylistic features of the building were designed by Emperor Joseph II himself. According to the funeral speech given by his personal physician Giovanni Alessandro Brambilla (1728–1800), it was Joseph II who had drafted the drawing.44

This simple fact suggests that the distinctive shape of the Narrenturm did not serve medical purposes but rather was an aesthetic means of serving a political goal. The edifice provided an impressive landmark of imperial power and perhaps also of purposefully created mysteriousness.45 The tiny octagonal tower, originally situated at the center of the tower’s roof (but missing today) probably symbolized imperial perfection in this case, too, reflecting a tradition that can be traced back to Roman and medieval rulers, who used the existing interpretative pattern of equating the number of eight with the sacred, in particular in architecture.46

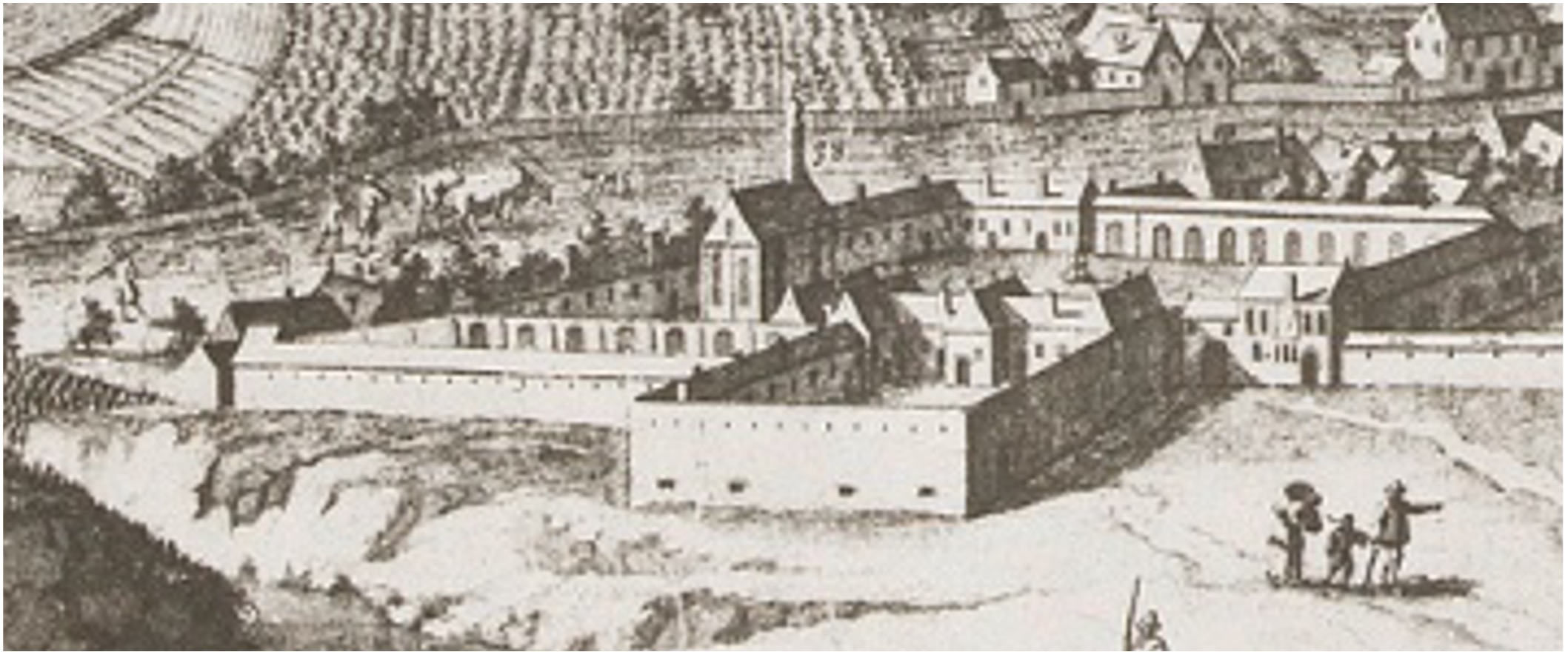

Figure 4. The old Lazareth located in Alsergrund suburb,

the second site of the Viennese madhouse since 1792.

(Detail from copper plate—view of Vienna by Folbert van Alten-Allen, 1686; CC)

Already around 1790, the Narrenturm proved insufficient to meet the growing demand for accommodations for severely mentally disturbed persons in Vienna and Lower Austria. The authorities reacted to this situation by refurbishing the former Viennese lazaretto near the general hospital (see Fig. 4) for this purpose, a measure already proposed by Quarin in 1784. This institution opened in 1792 as an asylum for about 150 so-called “ruhige Irre” or “peaceful insane” (a behavioral classification meaning patients who were considered mentally ill but not violent, not disruptive, and not considered dangerous), ending the provisional accommodation of “completely harmless fools” in other public buildings in the Alsergrund district, a practice that was followed from at least 1786 due to the lack of space in the Narrenturm.47 Irrespective of the administrative connections of both madhouses (the Narrentum and the lazaretto) to the general hospital, apart from a primary physician who served the needs of the patients part-time in the 1780s (in addition to providing treatment for patients in the general hospital), the medical staff consisted of only one surgeon and his assistant. According to an instruction to the staff dating from 1789, one male and two female keepers (Wärter) were assigned to each floor of the building, which formed a department. This document also refers to so-called “helpers” (Gehilfen), but it does not specify their numbers.48

Late eighteenth-century observers did not form a favorable judgement of the accommodations within the building either. Apart from the fact that the so-called “raving mad” were chained to the wall within their respective “containers” (Behälter), the “peaceful insane” also had to cope with inappropriately low beds and spartan furniture (a bed, a table, and two chairs) in their small, dimly lit cells. Furthermore, the central heating system, praised as innovative when the edifice was built, could never be used properly, as it did not warm up the cells due to a technical failure which could not later be corrected, even though staff tried to heat the spaces with ovens positioned in the circular, connecting corridors. The lack of a separate water supply in the building aggravated problems, especially sanitary hygiene, because the water needed had to be carried there from the general hospital. The wish to spare costs for this probably led to stronger limitations in the use of water as would have been in place otherwise. This was particularly disadvantageous, because the second largest-scale technical innovation in the construction of the Narrenturm, the waterless system for the removal of excrement from the patients’ cells, also could not be used after the 1790s, probably due to the gradual obstruction of the pipes by excrement, thus causing an intolerable stink in the building. These conditions are detailed in the testimony of Johann Peter Frank, who ordered that these outlets be bricked up and replaced with the simple, time-tested tool of the chamber pot, which in turn made the regular manual removal of excrement from each individual cell a necessity.49

Therapeutic measures of any kind were considered desirable in principle, but in practice, due to the small number of medically educated staff, they were only rarely used. Hence, within the asylum, the mode of cure overall was very simple and mostly consisted of simple diet, as a contemporary observer reported in 1797.50 We cannot rule out the possibility that, even at this initial state, so-called moral treatments were put to some use, along with psychological cures, such as the contemporary innovations highly praised by progressive early psychiatrists and doctors for the mentally ill, above all Pinel, Tuke, and Chiarugi in France, England, and Italy.51 However, there is no systematic documentation indicating the use of such approaches before the 1790s.

The situation began to change around 1800, when a traveler acknowledged the compassion and concern apparent in the psychological treatment of inmates conducted by primary physician Franz Nord (1761–1822), who had succeeded Johann Peter Frank as primary physician for the madhouse in 1795 and since 1805 had also served as director of the general hospital.52 His medical work with the mentally ill was praised by others, but difficulties in the organization of the finances of the institution and/or his habit of “openly confessing the defects of the institution on several occasions and demanding adequate remedies”53 led to his dismissal in 1811.54

In contrast to the use of psychological remedies, which probably remained rare, somatic treatments, which followed the tradition of humoral pathology, apparently were quite frequently used from the outset (i.e., from 1784), as they were seen as more time efficient. As for pharmacological therapies, detailed descriptions from the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries remain scattered. However, as a travel report published in 1802 reveals, two traditional purgantia—Cantharidin, contained in Spanischen Fliegen (Spanish flies, Cantharis vesicatoria and Brechweinstein (Antimonium tartaricum, tartar emetic) – were used by Nord in a relatively cautious manner as an externally applied irritant. Orally administered drugs were not mentioned by name in the relevant report but rather were described as “strengthening and stimulating substances.”55

As a general result of the centralization process of the Viennese health care system, survival and recovery rates did not increase as had been hoped and expected. On the contrary, mortality rates increased due to the more rapid transmission of infectious diseases among the now densely populated wards in hospitals. This seems to have been the case in the Narrenturm as well, as least to some extent. The earliest records on the numbers of inmates, admissions, releases, and deaths56 cannot be aggregated to offer a fully consistent and clear picture, as some of the data are lacking, but Vitecek nonetheless persuasively demonstrates in his study that during the first period of about 16 and a half years from April 1784 to August 1801, there were 3,201 registered admissions to and 2,719 departures from the asylum altogether. With 729 fatalities among the inmates, the total mortality rate for this period of 16.5 years comes to 23 percent or 27 percent (depending on the mode of calculation). Annual mortality, of course, was much lower, but it still varied between approximately five and ten percent. This was quite high in contemporary terms as well. The same statistical data prove that, despite the stereotypical opinion that admission to the asylum equaled long-term interment (perhaps until the patient’s death), a considerable number of the inmates, slightly more than 100 on average, were actually dismissed each year. For the total time span between 1784 and 1801, this amounts to 54 percent of those admitted and 63 percent of those who were released. Transfers to other departments of the general hospital came to about ten percent annually. Therefore, though the ratio of inmates regarded as cured remains unknown, even during this first stage, when many patients in the Narrenturm had to endure inhumane living conditions aggravated by the absence of proper therapeutic treatments, more than half of the admitted patients survived the institution and were discharged sooner or later. Among the early patients, there were more men than women (ca. 60 percent versus 40 percent). Furthermore, the figures also reveal that male inmates had lower chances of survival than female inmates.57

Within the former lazaretto, which was repurposed in 1792 to serve as a department for “peaceful fools” and particularly convalescent patients, overall living conditions were better than within the Narrenturm. Yet it was not until 1803 that a physician and a surgeon were hired exclusively for this department. They were responsible for providing care for both incurable and curable patients, with emphasis on the latter as the preferred future target group. From 1807 onwards, the political authorities expected newly admitted individuals suspected of madness to be transferred first to the lazaretto for observation and not immediately to the Narrenturm, at least in the more worrisome cases. Yet, as Vitecek points out, the differentiating criterion for admission was not supposed curability but the perceived difficulty of handling their behaviors. Inmates were thus divided into groups based on the classification of raging and impure on the one hand and the classification of peaceful and clean on the other.58

These distinctions were useful in the disciplinary functioning of the asylum, an aspect on which the contemporary reports on the Narrenturm only rarely touch. However, the physician Michael Wagner, in an appendix to his early translation of Philip Pinel’s psychiatric manual published in 1801, lists “fasting, straitjacket, straps, handcuffs and leg irons” as “usual means for taming, applied when circumstances demand.”59 In turn, useful occupations, ranging from unskilled work to qualified handicrafts and even office activities, were used for therapeutic and disciplinary purposes in cases of patients who were regarded as suitable subjects for this approach, as reported on several occasions.60

Salzburg’s Early Madhouse and the Sister Institutions of

the Viennese Narrenturm in Linz and Graz, ca. 1780–1800

Salzburg was the site of first asylum on the territory of present-day Austria, though it was an independent ecclesiastical principality within the Holy Roman Empire until its dissolution in 1806. Moreover, the establishment of a hospital for the Sinnlose (senseless) and Tollsinnige (mad-sensed) in 1783 appears to have been more nominal than functional, as suggested by the sources cited in the first more detailed historiographic account of Irrenwesen im Herzogthum Salzburg, by Ignaz Harrer (1826–1905), a former mayor of Salzburg.61 Remarkably, this madhouse was also founded as a consequence of personal initiative. This is indicative of the emerging and intensifying societal interest in the relationship between reason and madness among the social elites in Austria and Southern Germany during the last decades of the eighteenth century.62

Augustin Georg Paulus (1695–1777), a surgeon and administrator of several municipal institutions in Salzburg63 (including the Bruderhaus hospital), bequeathed the majority of his estate to charitable causes. Following his death, his widow allocated the substantial sum of 4,000 florins specifically to the improvement of accommodations for the furiosi (the raving mad). Until that point, such persons had been confined in Kötterl (lockable wooden hutches) beneath Saint Sebastian Bruderhaus on Linzergasse (in the suburb am Stein), a situation increasingly deemed inadequate. Archbishop Hieronymus Colloredo (1732–1812), a leading proponent of the Catholic Enlightenment in the region in the late eighteenth century,64 took a personal interest in the matter. He contributed an additional 4,000 florins, solicited further donations, and ultimately initiated the construction of a new facility on the grounds of the existing Bruderhaus. The aim was to provide a space for those “degraded to the level of animals by their defect of reason,” where, through appropriate care, they might recover their mental faculties.65 Echoing the model set by Joseph II for Vienna, Colloredo decreed in 1800 that the new institution should admit only individuals who, due to their raving behavior, would pose a threat “to the lives and property of the other human beings in society.”66

However, the following year, Dr. Michael Steinhauser von Treuberg (1754–1814), city physician and chief medical officer at the Johannis hospital in the suburb of Mülln,67 submitted a report that, in my assessment, clearly demonstrates that little had changed in practice since 1783. The few mentally ill individuals housed at the Bruderhaus site were, in fact, still kept in the old wooden hutches, while the new building had partly collapsed and the part that remained intact was being used as a school. Steinhauser concluded that “the structure was not yet at all in a condition to serve a medical function,” and the facility would only be able to serve as the desperately needed institution of a madhouse are repairs had been done and the school that was functioning in the building had been relocated.68 Thus, with regard to the Narrenhaus in Salzburg, although there were indeed plans to found a new asylum and a new edifice was built in the late eighteenth century, the new institution did not become practically operational until 1801. In this case, too, economic difficulties, which got increasingly pressing over the course of the 1790s, were also a decisive factor.69

Figure 5. The building of the former Prunerstift in Linz,

partially used as madhouse between 1788 and 1867. Recent view, photography

taken by Volker Weihbold, Oberösterreichische Nachrichten (by courtesy).

As had been true in Lower Austria, the establishment of madhouses in Upper Austria and Styria was initiated by Joseph II, but developments in these provinces followed somewhat different trajectories. In Linz, the capital of Upper Austria, the new madhouse was established by imperial decree in 1788. A large charitable institution originally founded in the 1730s was repurposed. This institution had been founded thanks to a generous testamentary donation of more than 175,000 florins by Johann Adam Prunner (1681–1734; often spelled Pruner), a merchant and long-serving mayor of Linz. His endowment had been intended to provide shelter and sustenance for no fewer than 81 impoverished townspeople. Situated just to the east of the city walls near the Danube River (the address today is Fabrikstraße 10, Linz), this charitable foundation enjoyed a favorable location, though it was considered somewhat unhealthy due to the foul odors from a nearby rivulet and surrounding industrial activities. By 1785, however, it had come to the attention of state authorities as a problematic institution, largely because inflation had created a growing financial deficit. Following a personal visit to Linz in 1786, Joseph II ordered a complete restructuring: the orphans and elderly residents without serious health problems were to be relocated to private homes, and the building itself was to be repurposed as a state-run facility comprising a general hospital, a madhouse, a labor and delivery department, and a foundling asylum. The plan for a general state hospital in Linz was not pursued, however, in part because the two existing hospitals operated by religious orders were considered sufficient. Likewise, the idea of a foundling asylum was soon abandoned, and foundlings instead were placed in foster care outside the city. 70

Ultimately, the only facilities that were permanently established at the so-called Prunerstift (see Fig. 5) were to provide housing for the mentally ill and unmarried pregnant women. When the madhouse began operations in 1788, it occupied only one side wing of the building and housed eight individuals, two men and six women. These individuals had previously been provisionally accommodated at the city’s lazaretto, which had served this function since 1768.71 Plans, however, referred to a total of 24 cells, located within both rear side wings of the building, to be used for the confinement of the mentally ill, with one wing designated for male patients and the other for females. The existing cells, which, in accordance with Pruner’s will, were slightly larger than those of the Capuchins, were fitted with wooden grids for that purpose. While this construction created significant noise disturbances for the inmates, it was considered advantageous for heating purposes, since the cells themselves were not equipped with stoves but instead were warmed only indirectly by heating in the corridors during winter.

The madhouse in Linz, along with the adjoining delivery house, was managed by an administrator of the foundation. As in Vienna and other early asylums in Austria before 1800, no physicians were permanently employed to treat mentally ill inmates at the outset. Medical visits were arranged when perceived as needed, primarily for somatic conditions. Two attendants, one man and one woman, were responsible for daily provisions, nursing care, and supervision of the inmates. Patients considered dangerous were chained to their beds, and, as was true of the Narrenturm in Vienna, visitors frequently remarked on their deplorable conditions, which included oppressive darkness, loud noises, and particularly the stench caused by excrement on the floors, which could not be adequately removed. These issues likely affected not only the inmates but also the staff who lived in the institute and thus was exposed to the same conditions.72 Nonetheless, no substantial structural improvements appear to have been made in the first decade after 1800, and the number of inmates probably remained close to the originally planned capacity of 24 until at least 1815.

The madhouse in Graz was similarly founded due to the personal intervention of Joseph II. In 1781, the emperor had instructed the regional government in Graz to conduct a survey of existing charitable institutions and foundations across Inner Austria,73 including all hospitals, workhouses, and the large poorhouse already operating in Graz.74 In March 1784, Joseph II personally visited in the Styrian capital for five days, during which time he is credibly reported to have toured “all public institutions” in the city. At the end of his visit, he issued an imperial Handbillet to Governor Johann Franz Anton von Khevenhüller (1737–1797) outlining significant structural changes, including the repurposing of the existing poorhouse in the Gries suburb for a future medical hospital, which was also to accommodate mentally ill individuals. This mirrored the approach already taken in Vienna.

Figure 6. The former Capuchin cloister in Graz, which was used as madhouse

between 1788 and 1873. Recent view, image from Google maps (3-D-view, 18.04.2025),

edited by C. Watzka. The rather small, muddled complex near the northeastern city gate

is displayed from the eastern direction in bird’s eye view.

However, preparations for such large-scale changes took time. During another visit to Graz in June 1786, Joseph II noted the vacancy of the former manor of the Upper Styrian cloister of Saint Lambrecht in Graz and reconsidered his plans. He designated that vast building, located at the edge of the city in the Paulustorgasse, to house the new General Hospital and another, smaller building across from it (the former Capuchin cloister in Graz, also vacant at the time) as the new madhouse. After some further delays, the madhouse in Graz (Paulustorgasse 11, see Fig. 6) officially began operations in December 1788.75

The first inmates were transferred to the madhouse from the various provisional locations around the city.76 By the end of 1789, the number of inmates had risen to 26, and by 1790, it reached 31. Initially, the institution was intended to house only “raving, demented, and furious” individuals. “Peaceful” people suffering from milder mental disorders were to be placed in the general hospital. An accommodation fee of 10 Kreuzers was fixed for the third-class patients, which included ordinary and poor persons. This fee was to be paid either by the patients or by charitable foundations responsible for their care. Interestingly, no distinction was made between fees for the general hospital and those for the madhouse. Yet from the outset, the entire General Hospital, to which the madhouse was organizationally linked, faced severe financial difficulties, which intensified in the 1790s. Meanwhile, the number of inmates increased steeply, from 31 in 1790 to 65 in 1795 and 78 by 1800.77

As in all other Austrian madhouses of the period, no specialized medical staff was employed to treat the mentally ill in Graz. This is revealed, for instance, by the official 1796 publication by Philipp Graf Welsperg von Primör und Raitenau (1735–1806), governor of Inner Austria at the time. This publication provided an overview of the structure of the poor relief institutions in Graz.78 The staff of the madhouse included the director and the administrator of the general hospital, who oversaw the institution, as well as the surgeon and assistant from the general hospital. Together, they were scheduled to supervise the inmates in pairs, alternating daily, and to monitor the work of the two “sub-supervisors” employed at the madhouse. The primary focus of these visits was to oversee the inmate’s “food, laundry, cleanliness,” and “custody,” especially to ensure protection against harm, whether self-inflicted or inflicted on others by the inmates. Doubtless, this concern for safety was one of the main reasons for the policy of isolating each inmate in a separate room or chamber.

Illness was largely understood in terms of somatic illnesses that could affect the insane. In such cases, the protocol was to transfer the patient to a “sickroom” within the madhouse or to the nearby general hospital, with medical assistance provided as needed. However, there was no mention of specific psychiatric or moral treatment. The focus was on preventing “mistreatment of any kind.” The accommodations provided for the inmates and the ways in which they were handled depended on the severity of their diseases and the dangerousness of their behaviors, according to Welsperg’s description. Those deemed dangerous were put in chains, while the raving were separated from the more harmless inmates. More peaceful patients were allowed “to walk in a locked courtyard or garden,” with men and women alternating. Inmates were encouraged to engage in “moderate occupations,” but only with the consent of the attending physician and only if accommodated free of charge. This clearly shows that this was intended more as a means to contribute to the costs of their stay than as a genuinely therapeutic measure.

Remarkably, the regulation explicitly excluded the admission of individuals from rural areas for whom nobody (neither family nor any community, authority, or fund) would cover the costs of their stay.79 One year later, in 1797, Graz, unlike other major cities in the Hereditary Lands, was occupied for the first time by French troops during the Napoleonic wars. While no major acts of violence were reported, the military occupation placed significant additional financial strain on the city and the region.80

Austrian Madhouses during the Napoleonic Crisis of

the Habsburg Monarchy: Survival under Precarious Conditions

In Austrian proto-psychiatry, even the modest plans to improve the living conditions of mentally ill inmates largely came to a standstill from the mid-1790s, and no significant initiatives in this direction were taken for more than two decades. The broader political and economic context was profoundly discouraging to any reform efforts, both ideologically and financially. As early as 1789, the Austrian Monarchy became deeply embroiled in a fierce struggle against the spread of democratic and liberal ideas, which had gained momentum across Europe in the wake of the French Revolution. From 1792 onward, this ideological confrontation escalated into military conflict. Particularly since the Third Coalition War of 1805, the Habsburg Monarchy faced existential threats and found itself teetering on the brink of collapse due to the immense loss of life and resources incurred in the wars against Napoleonic France, a country that, in the eyes of many Central Europeans, had shifted from a beacon of human progress to a source of imperialist aggression and repression.81

During the military campaigns of 1805 and 1809, even the Austrian capital was occupied by French troops, and this turmoil inevitably impacted the Viennese madhouse, too. At the time, both sites, the Narrenturm and the lazaretto, together housed 430 to 440 patients annually. These two years witnessed particularly high annual mortality rates: 17–18 percent in 1805 and 1809, compared to a relatively lower range of 9–12 percent in 1806, 1807, and 1808.82 The defeat of the Habsburg Monarchy in 1809 contributed dramatically to the temporary collapse of Austrian state finances in 1811, further paralyzing any institutional improvements. Even the seemingly modest proposal to appoint a single physician with full-time responsibility, on the basis of a salaried employment contract, for the Viennese madhouse was implemented only after the end of the Napoleonic wars.

Dr. Ignaz Eisl (born 1764, died after 1845), who served as primary physician at the madhouse from 1811 to 1826, in 1817 was formally relieved of all other responsibilities within the General Hospital of Vienna by decree of the Imperial Court Chancellery.83 He was then exclusively tasked with the treatment of the insane in both the Narrenturm and the lazaretto. On that occasion, a written directive originally prepared in 1814 was reissued by state authorities. This directive emphasized the two main duties of the primary physician: to prevent mistreatment of the inmates and to implement appropriate precautions to protect others from potential harm by the patients. Significantly, this document confirmed that a differentiated accommodation scheme was already in effect to determine whether a new patient should be admitted to the Narrenturm or the lazaretto, and to which ward specifically. The classification criteria included perceived “dangerousness, noisiness, uncleanliness, incurability, and inclination to escape.” Notably, the concept of moral treatment, which developed in late eighteenth-century England and France,84 is explicitly referenced in these instructions under the term “moralische Arzney.” The use of the then “modern” straitjacket as a means of physical restraint is also documented.85

As for the medical personnel, it is worth noting that Bruno Goergen (1777–1842), who later gained recognition as the director of the first large private asylum in Vienna (from 1819 onward), also served as a primary physician responsible for the mentally ill at the General Hospital from 1805 to approximately 1814.86 The exact division of responsibilities between Nord, Eisl, and Goergen during this period remains unclear, but it is likely that each was primarily assigned to one of the two facilities for a given timespan.

Even less is known about actual staffing and other fundamental organizational aspects at the smaller madhouses in Linz, Graz, and Salzburg during that period from about 1800 to 1815. This historiographic silence is in itself revealing, suggesting that few changes occurred, or at least no changes that were later regarded as positive or memorable by learned observers.

One notable exception is the case of Salzburg, where Ignaz Harrer (1826–1905),

later mayor of the city and an active reformer of its health and welfare institutions, took a keen interest in the development of a modern “Irrenanstalt” (insane asylum) in the 1860s.87 Drawing on archival sources, Harrer reconstructed the prolonged and difficult early history of psychiatric care in Salzburg, which started in the late 1770s. As mentioned above, until 1801, individuals suffering from severe mental illnesses had still been confined under harsh conditions in hutches attached to Bruderhaus hospital. Despite earlier intentions, a separate madhouse had not yet been established. In 1804, city physician Dr. Steinhauser, responsible for the treatment of the inmates, submitted a new report on the issue, indicating that large parts of the asylum had remained in a dilapidated state and were unfit for patient accommodation. Meanwhile, “only raving or severely unclean human beings” were held in the aforementioned huts, where prolonged stay was deemed both “unsanitary and unhealthy” by the rapporteur. Particularly illuminating are Steinhauser’s further remarks on the day-to-day operations of this rudimentary institution:

The staff appointed for all the sick [of the Bruderhaus hospital] consists of two old and weak women, who care for the patients and cook for them from the weekly [monetary] contributions made. These miserable contributions hardly suffice for the women to obtain the necessary food; the house provides only lodging, firewood, lighting,

and straw [for the inmates]. Thus, nothing remains—not even for a shirt or some medicine—and each visit by the physician or these women entails begging and personal danger. Particularly instructed staff and a fund supporting the physician’s psychological [sic] intentions, regarding the pharmacy, kitchen, and living rooms, but also contact, labor, walking, cold and warms baths etc., should be introduced.88

Among the therapeutic measures Steinhauser deemed appropriate were “serious coercive treatment, isolation, suitable diet, and adequate psychological use of the lucida intervalla [periods of mental clarity].” But he warned against excessive use of purgative medicines, which, in his view, either killed people or rendered them permanently “unreasonable.” Notably, Steinhauser admitted to having applied various traditional remedies to treat insanity, inherited from ancient and early modern medicine,89 during the “early stages of his medical career,” such as “opium, camphor, measures to cause suppurating wounds, starvation and thirst,” but (unsurprisingly to us today) without sufficient, lasting success.90 These brief but pointed remarks reflect a clear shift towards the then emerging approach of moral treatment and a distancing from older, somatic-based approaches that dominated early modern cures.

Sobering commentary from the principal medical council, addressed to the government of the Salzburg principality, explicitly emphasized the dangers of the “current miserable and disordered situation of the institution for the insane, which brings the unfortunate [inmates] closer to the edges of ruin.” Yet, at the same time, it cautioned that no substantial remedy for this situation could be formulated until more financial resources were found to expand the institution’s potential.91 In the years that followed, local authorities attempted to address the problem by initiating a complete relocation of the institution and soliciting funds from private benefactors, a process that began in 1807 but took more than a decade to complete.92

Wider geopolitical turmoil and economic instability (warfare and economic hardships all over Europe) contributed to this prolonged stagnation. Salzburg, in particular, suffered severely. The city was occupied and plundered three times between 1800 and 1809 by French and Bavarian forces. The Erzstift (ecclesiastical principality) of Salzburg was dissolved in 1803, and the region became a part of the Habsburg Monarchy in 1805, only to be annexed by Napoleonic Bavaria in 1810 following Austria’s military defeat. Only after the final defeat of Napoleonic France in 1815 and a treaty concluded between Austria and Bavaria in 1816 did the country and the city of Salzburg become definitively incorporated into the Austrian Monarchy.93

Even less information appears to have survived regarding the two Josephinian madhouses in Graz and Linz during the “silent” period between approximately 1800 and 1815. However, some basic data on the institutions’ operations were preserved, mainly in nineteenth-century publications. For Graz, in his account of the 100-year anniversary of the city’s general hospital published in 1889, the Styrian medical historian Viktor Fossel provided annual counts of the numbers of patients, beginning in 1789. According to him, the asylum housed between about 60 and 95 inmates per year in the early nineteenth century, with a peak between 1801 and 1804. Numbers dropped to 70–80 for the period from 1805 to 1812, reaching a low point of 58 in 1814.94 While the reasons for this decline are not explicitly documented, it was likely due to a lack of resources rather than a decrease in the number of mentally ill individuals in the region.

In Linz, the Prunerstift was reportedly capable of accommodating 32 inmates at the time, as described in Benedikt Pillwein’s 1824 publication on the city and its institutions. Yet in 1800, only 14 patients were housed there, and by 1824, the number had increased only modestly to 22. These relatively low numbers were attributed to the requirement that non-local communities in Upper Austria had to provide for their own mentally ill.95

Similarly, the total number of inmates at the Viennese madhouse (comprising the Narrenturm and lazaretto) declined rapidly from around 500–570 in the first years of the nineteenth century to approximately 430–460 between 1804 and 1811. In the final years of the Napoleonic wars, the numbers rose only slightly, reaching about 480–520. A closer look at Viennese statistical data, particularly the numbers of annual admissions and dismissals, reveals that this decline resulted from a combination of moderately reduced admissions, increased discharges, and higher mortality rates.96

Institutionalized Custody and Care for the Insane

during the Early Austrian Biedermeier Period

Shortly after the peace treaties concluded by the Congress of Vienna, Austrian governmental authorities once again devoted attention to the problems of inadequate facilities and overcrowding within Austrian madhouses. In 1818, a decision was made by the Hofkanzlei (Court Chancery) which had a lasting impact on the structure of funding for the whole of the poor relief and health care system in the Habsburg Monarchy for at least half a century, as the relevant institutions were now differentiated in two categories, one relating to organizations dealing with “cases, in which the overall wealth of the state is endangered by diseases” and another for institutions with purposes deemed less urgent. The institutions that belonged to the first class were then regarded as “state institutions” and were entitled to receive subsidies from the imperial treasury. In addition to the lazarettos and other facilities for the prevention of epidemics, they consisted of hospitals for venereal diseases, homes for foundlings, and madhouses. The institutions that belonged to the second class, which included medical, maternity, and other kinds of hospitals and hospices, were considered “local,” and funding was to be provided by the communities that made use of them.97

On the regional level, in Lower Austria, efforts to ameliorate the living conditions of the insane within the existing institutions quickly led to the creation of an auxiliary branch designed to house patients deemed both relatively peaceful and incurable outside of Vienna. In 1816, first the empty former monastery of Mauerbach (20 kilometers west of Vienna) was briefly converted into an insane asylum, accommodating 30 to 40 chronically mentally ill individuals. However, this initiative proved short-lived. Just one year later, the government repurposed former cavalry barracks in Ybbs, considerably farther from Vienna but offering much larger capacity, to house 300–400 mentally ill individuals. These patients were accommodated alongside other dependent persons in need of care. Significantly, the institution in Ybbs operated without any structured therapeutic regime, reflecting the concept of a Pflegeanstalt (nursing institution), where the focus was not on medical treatment but on containment. This custodial approach drew criticism from the first physician formally appointed to care for the mentally ill there in the 1840s, Carl Spurzheim (1810–1872). Spurzheim lamented that the institution had functioned as little more than a mere “depot” for the insane until the start of his tenure there.98 Despite the establishment of the Ybbs facility, concern about the quantitative and qualitative inadequacy of psychiatric infrastructure in Vienna persisted.

Figure 7. Bird’s eye view of the planned asylum in Bründlfeld (never actually built).

Watercolor by architect Cajetan Schiefer (1791–1868) from 1823. Wien Museum

Inv.-Nr. 105717/26, CC0 https://sammlung.wienmuseum.at/objekt/525188/

As early as the 1820s, public and professional voices began calling for a new, larger, purpose-built mental asylum in Vienna. In 1822, the administration of the Vienna General Hospital acquired the extensive vacant grounds at Bründlfeld, situated near the hospital, for this very purpose. Architectural plans were soon designed for a vast and impressive Irrenheilanstalt (institution for curing the insane; see Fig. 7).

Nevertheless, the lack of funds or, rather, the lack of will among the political elites to invest considerable sums for such a purpose led to the collapse of this project in 1829 before any construction work had started.99 Following this failed initiative, no major public project to expand psychiatric institutions in Vienna was launched for nearly two decades, despite the urgent and growing demand within the city’s health care system.

Some small expansion of the infrastructure for psychiatric treatments in Vienna occurred in 1828, when a further space within the General Hospital (a hall large enough to accommodate approximately 20 individuals) was designated as an “observation room” for newly admitted patients suspected of mentally illness.100 The overall annual number of patients housed within the various facilities collectively known as the Lower Austrian Irrenanstalt in Vienna rose to slightly above 600 in 1816 and 1817, thus surpassing the figures recorded around 1800. This was followed by a modest decline to approximately 540–570 in 1818–1820, but patient numbers rose again throughout the 1820s to about 620–630 in the early part of the decade and to sums between about 700 to nearly 800 individuals by its second half.101

The existing sources provide little evidence, however, of any improvements to conditions from the perspectives of accommodation, care, and treatment during the second quarter of the nineteenth century. On the contrary, new therapeutic measures were introduced (particularly in the “observation ward”) that probably exacerbated patient suffering. The German psychiatrist Wilhelm Horn (1803–1871), who visited Vienna in 1828, described the frequent use of the so-called Cox’s swing, a mechanical device that rapidly rotated the restrained patient with the intention of inducing nausea and vomiting. Some contemporary psychiatrists viewed this reaction as both disciplinary and curative. Horn also observed the regular use of the “Mundzwinge,” a gag-like apparatus invented by Johann Autenrieth (1772–1835), which forcibly prevented patients from crying out.

Within the “regular” departments of the Viennese asylum, the Narrenturm and the lazaretto, therapeutic practices may have been somewhat less brutal by comparison. However, the physical infrastructure of these institutions was widely regarded insufficient. Franz Güntner (1790–1882), who served as primary physician of the madhouse from 1826 to 1831 and succeeded Eisl in this position, still relied heavily on traditional remedies rooted in humoral pathology. Many of these medicines were designed to provoke strong bodily reactions, such as disgust, vomiting, diarrhea, and pain. Examples included the use of the “Autenrith’sche Salbe,” a skin-irritating ointment promoted by the aforementioned German physician, and the well-known tartar emetic. As a sedative drug, valerian (Valeriana officinalis) was commonly administered.102

In Graz as in Vienna, the available accommodation space within the madhouse had become grossly insufficient by the early nineteenth century. Around 1820, overcrowding had once again led to disastrous living conditions. The former Capuchin cloister, which contained only 26 cells and a few additional rooms for staff and infrastructural needs, was forced to house approximately 90 detainees over the course of one year, a situation reminiscent of the immediate post-1800 period. By 1825, the annual number of inmates had surged even to 130. Even if the number of individuals present at any one time was considerably lower, the chronic lack of space necessitated that each small former monastic cell had to be shared by two or three mentally ill persons. This practice, especially in the case of agitated and raving individuals, could only be maintained through the constant use of mechanical restraints. In 1829, after more than a decade of planning, the next phase of the asylum’s expansion was finally realized. The institution was extended with the purchase of the so-called Röchenzaun’sche Häuser adjacent to it, which then were used in part for the asylum and partly for the Gebärhaus (birthing house) of the city. The urgency of this expansion is evidenced by the immediate and steep rise in the number of patients, which leapt to 168 already in 1830.103

No physician was employed to care specifically for the inmates of the madhouse after 1815; instead, medical responsibility remained a secondary entrusted to doctors of the general hospital in Graz. Even when the Styrian government formally petitioned, in the late 1820s, for the creation of a salaried post for a chief asylum physician (suggesting an annual wage of 200 florins, a sum markedly lower than that of a grammar school teacher, which came to 450–800 florins at the time), the request was denied by the authorities in Vienna. The position was ultimately filled without remuneration when Dr. Albert Ritter von Kalchberg (ca. 1800 – after 1877), the son of the wealthy noble landowner, historian, and politician Johann Ritter von Kalchberg (1765–1827), agreed to serve without salary in exchange for free accommodation within the asylum. It was not until 1832 that a financial compensation was approved for the asylum’s primary physician.104

Living conditions at the asylum in Graz remained harsh throughout these decades, as was openly acknowledged in early 1840s by Dr. Wenzel Streinz (1792–1876), who was then chief health officer of the whole of Styria. In his brochure Die Versorgungsanstalten zu Grätz, Streinz critically observed that the madhouse served primarily as a custodial facility rather than a therapeutic one:

According to its original and still current regulations, that institution serves the care of insane, raving, and lunatic persons, for whom accommodation in such a specifically designated facility appears necessary to render the outbreaks of their mental confusions harmless to them and others. Therefore, the madhouse in Grätz [sic] remains nothing more than a place of detention and nursing for such individuals, the vast majority of whom remained unhealed and spend [the rest of] their lifetime there—largely because they were already in a chronic and therefore incurable stage of illness. Nevertheless, occasionally single recoveries do occur, though they must be considered fortunate accidents, since all the conditions required for a systematically arranged curative institute for the mentally ill are still lacking.105

Remarkably, this was the same Dr. Streinz who had earlier served as chief health officer in Upper Austria and had become director of the Linz asylum after it was designated a state institution in 1824.106 Streinz advocated for the purchase of a new, more suitable facility for the mentally ill in Linz soon after his appointment. However, these efforts were ultimately thwarted due to financial concerns. In the absence of a new site, the existing building was modified to function, to the extent possible, as a proper asylum. According to Anton Knörlein (1802–1872), who became director of the institute in 1837, the reforms introduced by Streinz in the 1820s included the removal of the old, foul-smelling wooden flooring, the provision of proper equipment and laundry, and the abandonment of the use of chains as restraints. By the early 1830s, the numbers of inmates at the asylum in Linz also had risen considerably. Knörlein recorded 48 inmates at the end of 1833 and a total of 86 patients treated during 1834. Yet in Upper Austria the request for the appointment of a salaried physician was likewise rejected at the time by the Viennese authorities. A paid position for a doctor of medicine at the institute was only established in 1837, after the then-responsible physician Georg Meisinger (1799–1874) had resigned from his unpaid post.107

In Salzburg, the development of a dedicated asylum, understood as an institution with its own administrative structure and qualified, specialized appointed staff, had been envisioned since around 1780, but no concrete steps were taken in this direction until 1815, as previously noted. This situation only changed after a devastating fire in 1818 destroyed large parts of the old suburb am Stein, which had been home to 1,154 persons, the Bruderhaus included.108 The hospitalized insane survived the blaze thanks to the efforts of compassionate townspeople, but those among them who were agitated had to be tied to trees outside the city gates for two days and two nights, until the so-called Kammerlohrhaus (a small former correctional house) in the suburb of Mülln was hastily prepared to receive them.109 Contemporary physicians soon judged this new facility inadequate for its use as an asylum for the mentally ill. It had only 17 small, dimly lit chambers, and its staff was considered insufficient. In 1830, three attendants were responsible for all care duties, and a lack of space restricted the number of inmates to around 20, which was less than needed. In contrast to the asylums in Vienna, Linz, and Graz, the Salzburg madhouse was never designated a state institute during the Vormärz period. Rather, it remained a locally administered institution until its closure in 1852.110 An 1850 account still described it, despite the presence of medical support, as “a mere institute for detention.”111

As mentioned in the introduction to this article, two additional asylums were founded between 1815 and 1830. In Klagenfurt, a former prison was provisionally adapted in 1822 to accommodate up to 40 mentally ill individuals.112 More significantly, in 1830, a new asylum was established in Hall in Tyrol, housed in a former monastery. Unlike its predecessors, this institution was explicitly designed as an Irrenheilanstalt, i.e., a facility for curing the mad. Thus, it was the first such functioning institution in the Habsburg Monarchy. The subsequent development of this asylum, along with the development of the other asylums after 1830, lies beyond the scope of the present study.113

Conclusion

The article has demonstrated, in broad consensus with the secondary literature on the subject that in the Austrian context, the Enlightenment era brought with it a declared intention to treat individuals suffering from serious mental disorders humanely and, as far as possible, to cure them through the methods of emerging psychiatry. However, neither sufficient political and social attention nor, more crucially, an ethical commitment to invest adequate financial resources accompanied this ambition. The nascent Josephinist welfare system of late eighteenth-century Austria was generally shaped by a paternalistic if not outright autocratic ethos. In this framework, the primary goal of early public madhouses was clearly the preservation of public order and not to nurture or further the wellbeing of the inmates. Even if such institutions were, with a few possible exceptions, not purposefully used for the interment of politically inconvenient but mentally sound individuals, their core function remained custodial, not therapeutic.114

Providing truly adequate living conditions for the mentally ill would have required more spacious and appropriate housing and also a significantly larger and better-trained staff. This, in turn, would have incurred considerably higher costs, resources that neither the imperial court nor the central or regional authorities nor even local communities were willing to provide, especially not for the vast majority of inmates, who hailed from ordinary or poor family backgrounds. In contrast, wealthier individuals and those of higher social status who suffered from mental illness often had access to private care at home or could be accommodated in one of Vienna’s private asylums.

Apart from the inmates themselves and, in some cases, their family members, the staff of these early mental asylums were those most consistently confronted with the harsh realities of contemporary asylum life. Physicians, surgeons, supervisors, administrators, and occasionally priests, as the most educated and highest-ranking professional groups involved, often gave sobering descriptions of the conditions in the asylums and the treatments sometimes used. Many of these accounts adopted an explicitly critical stance towards the institutions in which their authors worked. In contrast, the experience and perspectives of lower-ranking staff, such as keepers, servants, nurses, and so-called “old women,” are only rarely documented and thus remain largely inaccessible to historians.

Personal testimonies of inmates themselves from the early phase of institutional psychiatry are similarly scarce. Where they exist, these rare accounts are of particular value for research into the history of psychiatric patients.115 However, a deeper exploration of these sources, from the perspective of patient history, lies beyond the scope of this overview, as does any look into the early stages of academic psychiatry in Austria, which, at least from the perspective of publications, was limited in quantity and, with a few exceptions, also of limited importance for the further development of the discipline,116 at least until the 1830s, when Ernst von Feuchtersleben (1806–1849) published Zur Diätetik der Seele. The focus here instead has been on fundamental institutional and structural aspects of the emergence of psychiatry in Austria, especially with regard to the early developments and limitations of public asylums during the late Enlightenment and Vormärz periods.

Bibliography

Ammerer, Gerhard, and Carlos Watzka. Der Teufel in Graz? Besessenheit und Exorzismus am innerösterreichischen Hof 1599/1600. Graz: Leykam 2020.

Ammerer, Gerhard, Nicole Bauer, and Carlos Watzka. Dämonen: Besessenheit und Exorzismus in der Geschichte Österreichs. Salzburg: Pustet, 2024.

Ammerer, Gerhard, Alfred Weiß. Strafe, Disziplin und Besserung: Österreichische Zucht- und Arbeitshäuser von 1750 bis 1850. Frankfurt am Main: Lang, 2006.

Ammerer, Gerhard. “Exorzismus und animalischer Magnetismus als Behandlungspraktiken in der Frühen Neuzeit.” Virus. Beiträge zur Sozialgeschichte der Medizin 13 (2015): 35–53. doi: 10.1553/virus13s035

Baumgartner, Jutta et al. “Die Flammen lodern wütend”: Der große Stadtbrand in Salzburg 1818. Salzburg: Stadtarchiv, 2018.

Beales, Derek. Enlightenment and Reform in Eighteenth-Century Europe. London: Tauris, 2005.

Bell, David. “For a New Social History of the Enlightenment: Authors, Readers, and Commercial Capitalism.” Modern Intellectual History 20, no. 2 (2023): 663–87. doi 10.1017/S1479244322000087

Besl, Friedrich. “Die Entwicklung des handwerklichen Medizinalwesens im land Salzburg vom 15. bis zum 19. Jahrhundert.” Miteilungen der Gesellschaft für Salzburger Landeskunde 137 (1997): 7–112; 138 (1998): 105–296.

Brambilla, Giovanni Alessandro. Rede auf den Tod des Kaisers Joseph II., gehalten in dem Versammlungssaale der K. K. Josephinischen medizinisch-chirurgischen Akademie im April MDCCXC. Vienna: Alberti, 1790.

Brenner, Andrea. “Der Wiener ‘Narrenturm’ und seine PatientInnen.” In VorFreud: Therapeutik der Seele vom 18. bis zum 20. Jahrhundert, edited by Carlos Watzka and Marcel Chahrour. Vienna: VdÄ, 2008.

Brettenthaler, Josef. “Vom alten ‘Irrenhaus‘ zur Landesnervenklinik.” In Drei Jahrhunderte St.-Johanns-Spital Landeskrankenhaus Salzburg, edited by Josef Brettenthaler and Volkmar Feuerstein. Salzburg: LKH, 1986.

Dietrich-Daum, Elisabeth, and Maria Heidegger. “Menschen in Institutionen der Psychiatrie.” In Psychiatrische Landschaften: Die Psychiatrie und ihre Patientinnen und Patienten im historischen Tirol seit 1830, edited by Elisabeth Dietrich-Daum, Hermann Kuprian, Siglinde Clementi, Maria Heidegger, and Michaela Ralser. Innsbruck: IUP, 2011.

Dietrich-Daum, Elisabeth and Michaela Ralser. “Die ‘Psychiatrische Landschaft’ des ‘historischen Tirol’ von 1830 bis zur Gegenwart – Ein Überblick.” In Psychiatrische Landschaften: Die Psychiatrie und ihre Patientinnen und Patienten im historischen Tirol seit 1830, edited by Elisabeth Dietrich-Daum, Hermann Kuprian, Siglinde Clementi, Maria Heidegger, and Michaela Ralser. Innsbruck: IUP, 2011.

Dietrich-Daum, Elisabeth, and Maria Heidegger. “Die k. k. Provinzial-Irrenanstalt Hall in Tirol im Vormärz – eine totale Institution?” Wiener Zeitschrift zur Geschichte der Neuzeit 8, no. 1 (2008): 68–85.