Živnostenská Banka (Trades Bank) and Its Participation in the Banking  Consortia/Syndicates of Interwar Czechoslovakia*

Consortia/Syndicates of Interwar Czechoslovakia*

Eduard Kubů and Barbora Štolleová

Charles University

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.; This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Hungarian Historical Review Volume 13 Issue 4 (2024): 533-558 DOI 10.38145/2024.4.533

One of the characteristic features of the development of the Czechoslovak economy in the interwar period was its progressive concentration and increasing organization, whether initiated from above (the persistence of a higher degree of state interventionism) or from below in the sense of voluntary cooperation and clustering across the business environment. In addition to the traditional associations for carrying out business, such as joint-stock companies, public companies, limited liability companies, and others, which were legal entities and were usually established for an unlimited period of time, new instruments of cooperation were becoming more and more common. These were networks of cartels, conventions, gentlemen’s agreements, and syndicates which restricted the free market. The study sheds light on characteristic forms of bank-to-bank cooperation, namely consortia/syndicates, using the example of the largest and most important Czechoslovak bank of the interwar period, Živnostenská Banka pro Čechy a Moravu v Praze (the Trades Bank for Bohemia and Moravia in Prague). It points out the relatively large number of consortia and offers a typology derived from their functions.

Keywords: banking consortium/syndicate, Czechoslovakia, interwar period, Živnostenská Banka (Trades Bank)

Until the end of World War I, the economies of the Bohemian lands and Upper Hungary were firmly embedded in the Danube monarchy. Their development and modernization were closely linked to economic, social, cultural, and, last but not least, political developments. A key milestone was the abolition of serfdom in 1848 and the gradual opening of space for the formation of civil society and entrepreneurial activity. A further impetus to the dynamics of development in the Bohemian lands was given by the Austrian defeat in 1859, which meant the loss of the advanced northern Italian provinces and accelerated the transfer of the industrial core of the monarchy to the Bohemian lands. Hand in hand with this was the move towards the adoption of the February Constitution (1861) and the strengthening of the development of representative institutions of the legal order, both in the field of civil law and the legal regulation of the business environment. Viewed from the perspective of big business, economic modernization was a matter for the national German and, hence, Jewish-German elites. At the end of the nineteenth century, the Czech elites were only just beginning to play a more prominent role.1

The predominance of the German-speaking business milieu in the Bohemian lands was not only marked in traditional industries but also in industries characterized which were part of the so-called Second Industrial Revolution (the second wave of industrialization). The basis of the capital market in its large business segment developed in the same way. It was characterized both by the establishment of branches of big Viennese banks and by the formation of joint-stock financial institutions linked to private banking. A smaller but later nevertheless extremely important stream of financial institutions in the Bohemian lands was represented by the concentration of the national Czech capital. Its key source was the Schulze-Delitzsch type credit cooperative movement, which gained strength in the 1860s. In 1868, Živnostenská Banka was founded as their central financial institution. In the first decade of the twentieth century, although it still retained its provincial character and headquarters, it was one of the six largest Austrian big banks. In contrast to the Viennese institutions (and this was also true of other Czech national banking institutions), Živnostenská Banka (Trades Bank), despite its generally high turnover, financed mainly medium-sized and smaller businesses. Before the fall of the monarchy, even the nascent Czech national business was, for the most part, dependent for its financing on the Viennese big banks, which had a dense network in the Bohemian lands and were able to offer bigger loans on more favorable terms.

The establishment of the Czechoslovak Republic in 1918 dramatically changed the nature of the capital market in the Bohemian lands. Rapidly increasing inflation in Austria and Hungary, together with monetary reform in Czechoslovakia which pushed towards deflation, effectively cut domestic large firms off from their traditional financial connections in Vienna and Budapest. At the same time, the domestic capital market was insufficiently linked to the foreign capital markets of Western Europe or markets overseas. The significance of the various types of financial institutions and, above all, the significance of the individual national segments changed dramatically. The national Czech segment, led by Živnostenská Banka, gained the upper hand. The national German segment and the Viennese segment, in particular, were significantly weakened. The latter was partly dissolved in the national Czech environment through the nostrification of companies,2 which were partly “transformed” into commercially interesting and relatively strong segment of multinational financial institutions, both mixed (i.e. Czech-German) and financial institutions with foreign participation (mainly British and French capital).3

The redefinition of the capital market in the new republic had major consequences for its functioning. It reduced the power of the financial institutions. The Czechoslovak big banks were incomparably weaker and less experienced than their Viennese predecessors in terms of their potential and also in terms of their management skills. Moreover, in the early years of the republic, they concentrated on building and developing their industrial concerns by making large-scale investments in stock portfolios on their own account, which subsequently limited or even ruined their ability to offer companies credit. A new situation arose for the Czechoslovak industry in the sense that large-scale credit was more difficult to obtain and more expensive. The weakness and undercapitalization of the market became a characteristic attribute of the interwar period, undermining the modernization of industry and business in general.

The Capital Market and the Term Consortium

The transformation of the capital market also led to changes in the business strategies used by banks and the firms they financed. The new conditions generated new problems and in many ways changed the nature of cooperation. On the one hand, the efforts of large financial institutions to build their concerns as an exclusive sphere of influence of the banking institution and to define sharply themselves against the competition were strengthened. On the other hand, the limited amount of capital on the market created conditions for the expansion of existing and the formation of new or until then only infrequently used manners of cooperation, even of a relatively long-term nature. The tendency to establish closer cooperation was also supported by the development of the economic cycle, especially its protracted periods of depression, which was characteristic of most of the interwar period.

A signal of a higher or even new stage of cooperation among banks in the Bohemian lands and then Czechoslovakia was the establishment in 1917 of the Association of Czech Banks, which later became the exclusive professional association of the large joint-stock commercial banks in Czechoslovakia, including the domestic German banks. It was on the basis of this association that coordinated banking procedures concerning credit and other matters were developed, in particular the creation of a Czech and then Czechoslovak banking cartel (analogous to the Austrian cartel of 1907), which determined the conditions of capital and money trade, employment issues, and last but not least consultations on cooperation with the state (internal loans, nostrification of companies, etc.).4

One important form of cooperation was the so-called banking consortia. These associations were formed for a “temporary period” to carry out one or more transactions on a “joint account.” The legal regulations varied largely from country to country. In Cisleithania, they were based on the General Commercial Code of December 17, 1862,5 which was later incorporated into the legal system of the Czechoslovak Republic. The term “consortium” referred to a non-commercial company governed by commercial law, which wasn’t a legal entity, was not entered in the commercial register and did not necessarily require a written agreement (contract). The established terminology of the time referred to “occasional companies” or partnerships and “a metà” company. The term “syndicate” was also used in the literature of the time.6 The reason for entering into consortium agreements was usually the considerable size of the planned transaction and the possibility of distributing the risks associated with a particular deal among several parties.7 Consortium deals were often associated with the banking business. The expression “banking cooperative”8 or “association of banks”9 was also used at the time to describe the function of a banking consortium.

The number of consortium/syndicate-type agreements, which had been common in the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy before World War I, grew in Czechoslovakia in the 1920s and especially in the 1930s to such an extent that special units were set up in the large banks to manage them and keep separate accounts for these transactions.10 These units were referred to as consortium/syndicate departments. There were several reasons for their establishment, including perhaps most importantly the sheer number of contracts but also the specifics and complexity of keeping the agenda. This type of business was classified in contemporary manuals and textbooks as “more difficult” from the accounting point of view,11 and it was also demanding in terms of the actual negotiation and conclusion of deals and the calculation of profits and benefits achieved. Moreover, the data on consortium transactions were considered very “sensitive.”12 Essentially, they were to remain hidden from the staff of other departments of the bank.

Consortia of banks are subjects touched on only marginally in the older and contemporary literature as well.13 The discussion below outlines the mechanisms of these agreements and their economic impacts in the specific case of Živnostenská Banka as the most important financial institution in Czechoslovakia in the interwar period. It offers a typology of consortia according to the purposes and functions for which they were established as a starting point for further research. Specifically, it focuses on consortia that were founded (1) with the purpose of establishing a company or taking over and selling off shares, (2) to guarantee and place public loans and bonds of public corporations or the state, (3) to intervene in some fashion in market affairs, (4) to ensure the influence of the group of shareholders in the company (so-called blocking consortia), and (5) to secure business and credit connections of companies (credit). Last but not least, the discussion below also considers the roles of the consortium of banks for state credit operations as a specific consortium of this type. Some questions fall outside the scope of the study, including the banks’ arrangements arising from ordinary banking transactions (i.e. agreements on foreign currency transfers, etc.), as well as “syndicates” in the sense of a higher organizational level of the cartel, which were legal entities (e.g. import and export syndicates, cartel sales offices), and the forced syndication of smaller firms in the 1930s for the purpose of their rational state-directed concentration.

A Typology of Consortia with Participation of Živnostenská Banka

(According to Their Functions and Purpose)

As already indicated, Živnostenská Banka was the leading actor in the Czechoslovak financial sector in the interwar period. In 1919, its share capital amounted to 200 million Czechoslovak crowns (by 1937, it had risen to 240 million), and its reserves amounted to 97 million crowns. The bank formed a concern that included a wide range of diverse Czech/Czechoslovak enterprises, including agriculture, sugar, engineering, textile, chemical, electrotechnical, commercial, and other companies. In principle, the bank aimed for proportional representation of all major sectors of the national economy. Živnostenská Banka benefited from its close ties to the state apparatus, to which many of its senior executives as well as middle-ranking officials moved. In the 1920s, its exponents repeatedly held the post of Czechoslovak economic minister, most often the post of finance minister. At a critical time in the birth of the state, the bank provided financial backing for its administration, direct loans and underwriting/arranging long-term public loans (see below). The extraordinary influence of Živnostenská Banka on state economic policy derived from these facts.

Type 1. Among the most frequent consortium agreements with bank participation in the period under review were consortia to establish a company or to take over and sell off an issue of company shares.14 The “textbook” examples, manuals, and dictionaries of the time are based on this type of consortium agreement. A 1913 handbook of bank accounting gives the hypothetical example of Živnostenská Banka initiating the formation of a consortium to sell shares of an unnamed company.15 Two other credit institutions, namely the Česká průmyslová banka (Bohemian Industrial Bank) and Pozemková banka (Land Bank), joined as members of the consortium. Each of the members of the newly formed consortium participated in the project with one-third, with Živnostenská Banka managing the project. The consortium took over the shares of the unnamed company at a predetermined price (216 crowns per share) and subsequently provided for subscription at a price above the acceptance price (230 crowns per share). The project was settled in a joint consortium account held by the gerent (bank in charge), in this case Živnostenská Banka, which included expenses, interest, and commissions. Once the transaction was closed, the profit shares were transferred to the individual consortium members.16

The importance of consortium agreements in the context of the founding activities of banks before World War I was captured by Czech historian Ctibor Nečas, who analyzed the activities of Czech banks in southeastern Europe. Živnostenská Banka, like some other domestic banks, apparently participated in several agreements established outside the Bohemian lands. It participated, for example, in the consortium for the increase of the share capital of the Trieste steamship company, in the arrangement for the transformation of the Split marble mining company into a joint-stock company, in the consortium for the establishment of the Herceg-Bosna joint-stock insurance company, and in particular in the consortium for the establishment of sugar factories (Osijek, Vrbas, Szolnok).17 When issuing, buying, or selling shares, the consortium agreements did not always have to be large-scale funding projects. An example of a smaller consortium with the participation of Živnostenská Banka in the Czechoslovak environment (its other members were the Spolek pro chemickou a hutní výrobu or United Chemical and Metallurgical Works Ltd. and “Solo” Czechoslovak United Match and Chemical Works) include the sale consortium of “Solo” shares (“Solo” was both an object and a member of the consortium), which was established in the autumn of 1937 to place only 10,075 Solo shares on the market (i.e. approximately three percent of the company’s capital).18

In practice, the simple examples presented in the manuals took on different variations, sometimes highly sophisticated, and the agreements could display various asymmetries and specificities. During its existence, the consortium typically had a gerent, either permanent or it was administered on a parity basis, meaning that the participants rotated in leadership positions at set intervals (usually after a year). The shares of securities taken over were not always equal. Each of the participating banking institutions could participate with a predetermined quota. The circumstances of the issue, purchase, or sale of corporate shares could be (and in practice were) linked to other organizational actions of the bank (such as shareholding and financing).

Type 2. Another type of consortium agreement involving banks was consortia to guarantee and place public loans and bonds of public corporations or the state. For example, a consortium of banks could be formed to underwrite municipal loan bonds.19 An example of wide-ranging cooperation is the agreement of 13 national Czech joint-stock commercial banks (including Živnostenská Banka), four public financial institutions, and one Slovak bank with the Czechoslovak National Committee of November 8, 1918, i.e. only five days after the establishment of the Czechoslovak state. The subject of the arrangement was a state loan of “National Freedom” in the amount of one billion crowns. Based on this loan, debentures were issued bearing interest at four percent and maturing within four years. The loan was of great symbolic significance and the banks waived their usual remuneration and only claimed reimbursement of the costs of securing the loan, in addition to providing the state with an advance of 100 million crowns.20

Type 3. Consortia of banks could be set up to support the price of certain securities on the stock exchange. An example of an intervention consortium is the consortium referred to as “B” in the internal documentation of Živnostenská Banka. Five leading Czechoslovak joint-stock commercial banks and one private bank agreed to form it in 1920, namely on December 24, 1920. These were the Agrární banka československá (the Czechoslovak Agrarian Bank, or simply the Agrarian Bank), the Česká průmyslová banka (Bohemian Industrial Bank), the Böhmische Eskompte-Bank und Credit-Anstalt (BEBCA), the Pražská úvěrní banka (Prague Credit Bank), and Živnostenská Banka, which were supplemented by the private banking house of Bedřich Fuchs.21 The purpose of the consortium was to carry out intervention purchases and sales of securities on the Prague Stock Exchange. For this purpose, each bank deposited three million crowns in the syndicate account and the firm of B. Fuchs deposited two million crowns. A total of 17 million crowns was to be used for the intervention purchases and sales of the thirty companies defined in the agreement. These were companies in which the participating banks had a special interest and which were included in their concerns. Purchases of shares were to be made for shares with a quotation value of up to 1,000 crowns if they had fallen by ten percent, for shares with a quotation value of up to 2,000 crowns if they had fallen by seven percent, and for shares with a quotation value of over 2,000 crowns if they had fallen by five percent compared with the last exchange rate. Other provisions of the consortium agreement specified the aforementioned basic key. The consortium was managed by Prague Credit Bank and the account was held by Živnostenská Banka. The agreement was not limited in time. The members agreed later to terminate it on June 8, 1926. The account had a passive balance of 7.3 million crowns at that time. However, the securities depot in whose favor the intervention was made showed a lot of shares of 13 companies with an exchange rate value of 13.4 million crowns. The result of the consortium was therefore positive.22

Type 4. In terms of consequences, shareholder consortia or blocking consortia were among the most important. František Špička, the procurer of the Bohemian Industrial Bank and author of a comprehensive manual on bank organization and the technique of bank transactions from 1926, paid considerable attention to consortium agreements in the context of the interpretation of the tasks and activities of the industrial departments of banks, which “were intended to ensure that groups which individually do not have a majority in the company have a decisive influence on the company.”23 A characteristic attribute of this type of consortium agreement was that it was backed by the holding of an inalienable block of shares by the consortium members. The shares tied by the agreement served as a guarantee of the functionality of the consortium (the principle of exercising voting rights at general meetings of the companies was included in the consortium agreement). The consortium with the participation of banks and also often industrial or commercial capital (mixed consortium) served to ensure medium-term or even long-term influence on the company and was usually signed for five to ten years with an automatic renewal clause. It was also commonly referred to as a “blocking” consortium.24 Its primary function was to create a controlling block of shares, thereby “blocking” the influence of other minority shareholders. It often created its own specific institutional structure, consisting of a negotiating board the function of which was to decide on the course of action within the respective firm. In essence, this was a structure analogous to the organizational structures of individual firms. The consortium was an expression of the concentration of industrial and commercial capital and the concentration of banking power. Groups of banks could seek to influence or control a key group of producers in a particular branch, or in other words, to gain a monopoly or oligopoly advantage.

One example of a blocking consortium with the participation of Živnostenská Banka is the consortium of shareholders of the Akciová společnost pro průmysl mléčný (Dairy Produce Company or simply Radlice Dairy). The agreement was concluded on June 28, 1935 on the basis of 27,587 shares of the company, which at that time represented over 78 percent of its share capital.25 Participating in the agreement were Cukrovary Schoeller a spol, a.s. (Schoeller Sugar Factories and Co., Ltd., with 4,200 shares), the Bohemian Sugar Industry Company (with 4,800 shares), BEBCA (with 5,000 shares), the Ústřední jednota hospodářských družstev (Central Union of Agricultural Cooperatives, or ÚJHD, with 12,587 shares), and Živnostenská Banka (with 1,000 shares). The management of the consortium consisted of seven representatives, with each member-entity sending one representative and the ÚJHD (given the number of shares contributed) sending three representatives. The most important position within the consortium was held by Živnostenská Banka, despite the fact that it had the lowest stake. It asserted its influence through sugar companies and also through BEBCA. The consortium shares were placed in the custody and administration of Živnostenská Banka and the members committed not to sell or otherwise transfer their ownership rights during the term of the agreement without the express consent of the other members. Ownership transfers “within the consortium” were the exception. The purpose of the consortium was “to secure for its members a permanent influence over the management and administration of the Radlice Dairy, as well as to secure for its members proper representation in all the statutory bodies of the company and to secure the joint action of the members of the syndicate in all matters concerning the Radlice Dairy.”26

The representation of the members of the consortium on the Board of Directors, the Executive Committee, and the Board of Auditors of Radlice Dairy was in proportion to the shares bound by agreement, with the position of chairman belonging to the “group” of Živnostenská Banka and the position of vice-chairman to the ÚJHD. The consortium agreement included a specific arrangement regarding the appointment of the top management of Radlice Dairy. The deliberations within the consortium were conducted by voting in proportion to the shares bound by agreement (with one share being equal to one vote). This was done by majority vote, with matters requiring unanimous approval being explicitly named (pricing strategy, payment of dividends, amendments to the consortium agreement, including the purchase of shares for the consortium, entering into cartel agreements, reducing or increasing share capital). Externally, the members of the consortium committed to exercising voting rights in the statutory bodies of Radlice Dairy in accordance with the consortium’s resolutions. The agreement was non-terminable for five years and was to be automatically renewed for one year each time thereafter unless terminated by a member.27

The blocking consortium could be formed with the participation of domestic and foreign interest groups. This was the case with the Pražská železážská společnost (Prague Ironworks Company, PŽS), which had its main plant in Kladno. The consortium agreement concluded in the 1930s between Živnostenská Banka and the Mannesmann concern, represented by its plants in Chomutov (Mannesmannröhren-Werke), expressed the cooperation between the Reich-German capital group, which primarily sought to secure some influence on the company’s production profile and the supply of materials (ingots) for the Chomutov plant, and Živnostenská Banka group, which expressed the growing share of national Czech capital in the company and, above all, its interest in financing the company. The agreement, backed by 45.6 percent of the capital of PŽS (Mannesmannröhren-Werke providing 25.6 percent and Živnostenská Banka providing 20.21 percent), gave its participants a comfortable voting majority at the general meetings of PŽS.28

The consortium agreement was also adopted as a tool for coordination to regulate relations in the Prague company Philips Ltd. The agreement concluded on February 3, 1937 between the Dutch Philips (N. V. Philips Gloeilampenfabrieken in Eindhoven), Ringhoffer-Tatra, and Živnostenská Banka bound all the shares of the company (in the ratio 40:35:25) for ten years.29 The shares with a total nominal value of three million crowns were deposited in Živnostenská Bank’s depot. The agreement explicitly defined the motivations of the parties involved. The Dutch company was interested in “ensuring that the management of the Prague company bearing its name is in line with the Group’s business and technical principles.”30 Živnostenská Banka pursued the objective of maintaining a banking relationship with the company (specifically, the agreement stipulated a minimum scope of 80 percent financing on the relevant terms of the major banks in Prague). Ringhoffer-Tatra wanted to develop technical cooperation with Philips, and the agreement stipulated that “this effort should be taken into account to the maximum extent possible without disadvantaging Philips.”31 Živnostenská Banka and Ringhoffer-Tatra were guaranteed in writing a minimum yield on the shares tied up by the consortium (a net dividend of six percent). The Dutch company or a third party appointed by it was given the option of buying the shares belonging to the other members of the syndicate (within four weeks). A further agreement stipulated, within the same time frame, that the Dutch company would be obliged to take over the shares of Philips Ltd. from Živnostenská Banka and Ringhoffer-Tatra if they were offered to it.

Consortia of shareholders involving banks could in some cases bind blocks of shares in several different companies at the same time. This was true in the case of the shareholders’ agreements of Czechoslovak distilleries signed in the wake of the completion of the process of the so-called repatriation of Austrian capital following the financial collapse of the Österreichische Creditanstalt für Handel und Gewerbe (1931). In 1932, with the participation of the Agrarian Bank, the Družstvo hospodářských lihovarů pro prodej lihu v Praze (Cooperative of Agricultural Distilleries for the Sale of Spirit in Prague), the ÚJHD, and Živnostenská Banka, the Czech distillery consortium was established, the purpose of which was to “ensure a permanent influence on the management and administration” of the six explicitly named Czechoslovak distillery companies and to “ensure a uniform approach by the members of this consortium in all matters.”32 Later, the consortium was extended and included another banking institution (BEBCA) and, temporarily, the Vienna-based A. G. für Spiritusindustrie.33 The agreement provided for the establishment of a special “consortium leadership” to secure the agreement, to which the consortium members sent two representatives each. Later, detailed rules were drawn up specifying the roles of the “consortium leadership” and the “board of directors” and other mechanisms for the functioning of the syndicate.34

Type 5. Agreements to secure commercial and credit links of companies were also made in the form of consortia. These agreements involved the exclusive provision of the firm’s banking operations, including the direct financing by the consortium banks of capital-intensive operations that were beyond the realistic capacity of a single credit institution, either because of insufficient funds or because the amount of funds committed was so large that it created an increased risk of loss. The agreements on the provisioning of the commercial and credit link were separate contracts, and in cases of the formation of a “blocking consortium,” they could also be a direct part of the agreement.35 An example of banks acting jointly in the provision of credit can be seen in the draft credit agreement between Živnostenská Banka with BEBCA and the Kolin spirit potash factory and refinery from 1937. The banks established a credit framework of four million crowns. The first half could be drawn down without further conditions, while guarantees were required for the second half. For the duration of the agreement (five years), the company was obliged to concentrate all its credit and banking transactions exclusively with the participating financial institutions. The banks were to rotate in charge every year. They also stipulated that they would be the place for the deposit of shares for general meetings and the payout point for dividend coupons, for which they charged a quarter percent commission on the amount paid out. The agreement specified the loan guarantees (insurance). On request, the company was obliged to provide information on the employment of the company and the running of its business, as well as a balance sheet and an account of profits and losses.36

The Consortium Department at Živnostenská Banka had been in existence since January 14, 1921, and on that date, the credit affairs of 17 companies had fallen under it. The number of firms subsequently fluctuated. The department dealt with dozens of firms continuously,37 and in 1938, according to a uniquely preserved inventory, there were 32 firms. The size of credits ranged from hundreds of thousands of crowns to millions of crowns, mainly. Most of the organizational schemes of Živnostenská Banka were preserved after the war, but all indications suggest that the Consortium Department of Živnostenská Banka was organized directly under the General Secretariat of the Bank.38

There were essentially two techniques according to which consortium transactions were conducted. The first is of the type indicated above. The firm’s/subject’s overdraft account was held with only one bank, which handled all the firm’s transactions and at the same time set up share accounts for the other participating banks. “Turnover settlement” was carried out at regular intervals according to agreed quotas. The management of the account could belong to one of the banks for the entire duration of the agreement, or it could be rotated at agreed times. The second way of carrying out credit consortium transactions was for the firm to set up overdraft accounts with all the participating banks, which had the advantage of enabling it to carry out transactions with several institutions and thus benefit from the flexibility of one bank for certain operations. At fixed dates, the banks would then settle the balances between the accounts, bringing the account totals into balance with the agreed quotas. There were also cases when fixed quotas were set for particular types of operations and transactions (foreign exchange operations, etc.).39

If we focus on the specific banks with which Živnostenská Banka cooperated in the area of securing financing between the wars, we can say that the range varied and evolved over time. The preserved records of the consortium department show that Viennese banks were still frequent partners for Živnostenská Banka in the interwar period, especially in the early 1920s. Živnostenská Banka shared its clients in particular with the Österreichische Creditanstalt für Handel und Gewerbe, Bodencreditanstalt, and the Niederösterreichische Escompte Gesellschaft. The counterbalance to these gradually fading links was cooperation between Živnostenská Banka and domestic Czechoslovak banks. The most frequent were the alliances of traditional national Czech banks (Živnostenská Banka, the Agrarian Bank, the Bohemian Industrial Bank, and the Prague Credit Bank) and, less frequently, the cooperation of Živnostenská Banka with domestic German institutions, such as Böhmische Union-Bank and Böhmische Escompte-Bank. Cooperation with the latter German bank grew significantly only after its transformation into BEBCA, when Živnostenská Banka became directly involved in its capital.

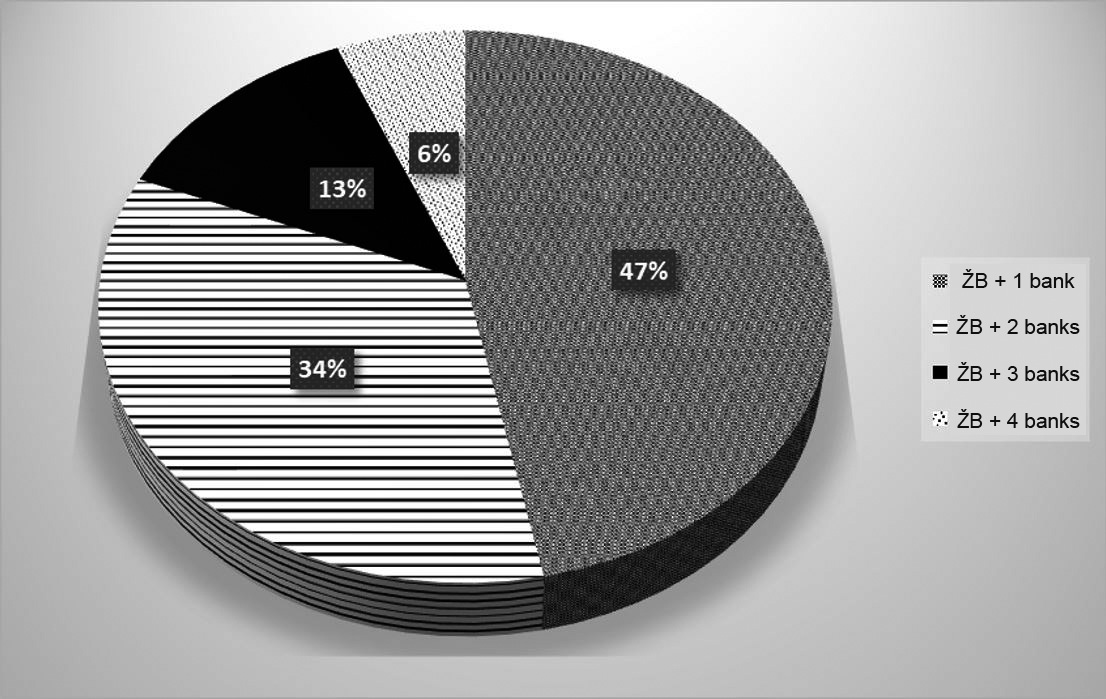

Figure 1. Banking consortia providing business and credit connections between companies with the participation of Živnostenská Banka as of 1938 (in percent)

Explanatory note: ŽB = Živnostenská Banka

Source: AČNB, fund ŽB, sign. ŽB/3959/1, list of consortium companies (undated).

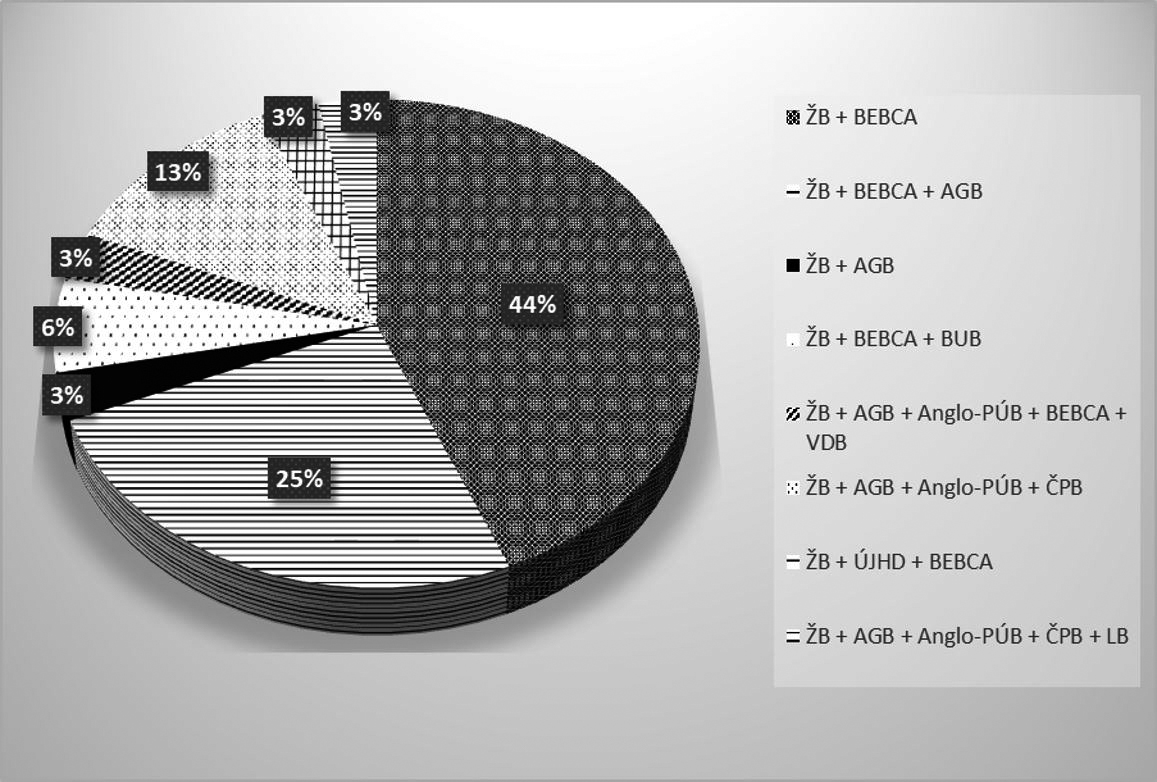

The post-1945 record of how consortium accounts were settled back to 1938 provides evidence of the nature of the cooperation between Živnostenská Banka and other financial institutions at the end of the First Czechoslovak Republic.40 For this year, as mentioned above, 32 companies are listed, which may seem like a low number, but the volume of transactions behind it is undeniably large. In most cases, these were profiling entities in their field of business with many dependent companies: PŽS, Explosia, Synthesia, the distillery complex, Poldina huť (Poldihütte/Poldi steel factory), Ringhoffer-Tatra, Vítkovické horní a hutní těžířstvo (Vítkovice Mining and Metallurgical Mining), Králodvorská cementárna (Königshofer Cement Factory), etc. In terms of the technique according to which consortium transactions were made, 17 companies were represented on the principle of a single account with an additional settlement between the participants (in nine cases Živnostenská Banka had the leadership position and in eight cases the leadership rotated). For 11 companies, parallel accounts were held with the participating banks, and the balances were settled according to quotas. For four companies, quotas were specified according to the type of transactions. The consortia in which Živnostenská Banka participated consisted of two to five banks. In 15 cases, Živnostenská Banka provided services in cooperation with one other banking institution, in 11 cases with two, in four cases with three, and in two cases with four other banking institutions (see Fig. 1). The most frequent partner of Živnostenská Banka in the provision of consortium loans was BEBCA (in 14 cases), in eight cases it was an alliance between Živnostenská Banka, BEBCA, and the Agrarian Bank (e.g. in the financing of distillery enterprises), in four cases Živnostenská Banka participated alongside the Agrarian Bank, the Prague Credit Bank, and the Bohemian Industrial Bank, and in two cases Živnostenská Banka coordinated with BEBCA and the Böhmische Union-Bank. The broad-based coalitions were rather unique and were based on the needs of the specific project. The specific configurations applied are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Formations under banking consortium agreements providing business and credit connections between companies with the participation of Živnostenská Banka as of 1938 (in percent)

Explanatory notes: ŽB = Živnostenská Banka; BEBCA = Böhmische Eskompte-Bank and Credit-Anstalt; AGB = Agrarian Bank; BUB = Böhmische Union-Bank; Anglo-PÚB = Anglo-československá a Pražská úvěrní banka (Anglo-Czechoslovak and Prague Credit Bank);

ČPB = Bohemian Industrial Bank; VDB = Všeobecná družstevní banka (General Cooperative Bank); ÚJHD = Central Union of Agricultural Cooperatives

Source: AČNB, fund ŽB, sign. ŽB/3959/1, list of consortium companies (undated).

A variation in the context of credit consortia was also a consortium that did not directly provide the funds but served as an intermediary and guaranteed credit from third-party entities (including another consortium of banks) with its assets.

Type 6. The consortium of banks for state credit operations was a unique type of banking consortium in interwar Czechoslovakia. This consortium was to act as an advisory body to the Czechoslovak government in financial policy, especially in its lending, either by banks directly or by intermediating loans and purchases on foreign markets. These roles were later supplemented by other roles, such as guaranteeing domestic and foreign loans and providing advances to the state, for example, for the purchase of grain. The consortium operated on the principle of quotas. In the autumn of 1919, the Czechoslovak Minister of Finance and the directors of nine Czechoslovak banks, six banks with Czech-language administration (the Agrarian Bank, the Bohemian Industrial Bank, the Moravian Agrarian and Industrial Bank, the Prague Credit Bank, the Central Bank of Czech Savings Banks, and Živnostenská Banka), two banks with German-language administration (the Böhmische Escompte-Bank and Böhmische Union-Bank), and one bank with Slovak administration (the Slovak Bank in Ružomberok/Rózsahegy), took part in the preparatory work for the establishment of the consortium.41 The consortium was thus the result of cooperation among a very broad spectrum of Czechoslovak financial institutions which were highly divergent in terms of their objectives and national profiles and fiercely competitive on the capital and money markets. The number of banks in the consortium was increasing, thus the quota of individual institutions decreased. The quota of Živnostenská Banka, which was set at 27.06 percent in the first year of the consortium’s operation, had fallen to 15.9 percent by the mid-1930s. Even so, the role of this banking institution remained exceptional, with by far the highest quota in the group of joint-stock commercial banks (other banks had a quota in the range of 0.4 to 6.6 percent). The most significant increase in the period under review was recorded by the public-law institutions, which negotiated fixed quotas (the highest was Postal Savings Bank with a quota of 20 percent, followed by Land Bank with a quota of 6 percent).42

The Consortium/Syndicate Transactions in the Balance Sheets of Banks and Živnostenská Banka in Particular

Published balance sheets of banks in interwar Czechoslovakia give only an idea of the importance of consortium deals in the context of their other business activities. On the asset side of the balance sheet, there was a separate column/item for “Participation” or “Consortium/Syndicate Participation,” which, according to contemporary interpretations of banking, was supposed to be a cumulative expression of the bank’s consortium/syndicate participations as well as participations in the basic capital of non-joint-stock companies,43 or a column summarizing all “financial participations in companies with which [banks] are linked by granting them credit, reserving influence on management.”44 According to data from 1922, this item cumulatively amounted to only 395.7 million crowns for all joint-stock banks in the Bohemian lands and 1.29 percent of their balance sheet total.45 In 1929, the item is represented by the amount of 1,054.2 million crowns (see Table 1). This indicates the growing importance of consortium transactions, though compared to other asset items, their share in the bank’s business activities still appears to have been relatively low. The dominant item on the side of officially reported assets for banks in the Bohemian lands was clearly the item “debtors” (65.86 percent of the balance sheet in 1929), followed by the items “bills of exchange” (8.70 percent) and “securities” (8.69 percent).46 The latter item also indicated the increasing involvement of banks in industrial and commercial business.

Table 1. Consortium and syndicate participation in the balance sheets of joint-stock banks in the Bohemian lands (Bohemia, Moravia, and Silesia) in 1929 (in thousands of crowns)

|

Banks with national Czech administration |

Banks with national German administration |

Banks with national mixed administration |

Banks in the Bohemian lands |

|

|

Consortium/syndicate participation |

445,560 |

158,165 |

450,437 |

1,054,162 |

|

Total assets |

13,930,371 |

6,276,616 |

11,138,301 |

31,345,288 |

|

Share of consortium/syndicate participation in total assets |

3.20 percent |

2.52 percent |

4.04 percent |

3.36 percent |

|

Source: Statistická příručka republiky Československé. vol. 4, 260. |

||||

As mentioned above, consortium agreements were among the types of deals that were considered highly sensitive (even classified). Antonín Pimper, an expert on the development of Czech banking at the time, drew attention to the fact that banks’ shares in industrial and commercial businesses often tend to be weighed differently in accounting and “usually represent secret reserves for the institutions in question.”47 In some banks, it has become common for these shares to be balanced at the nominal share value and not at the current rate. The current rate could have been several times higher, but the nominal share value was given instead to reduce the figure shown in the final balance sheet. As a specific case of a bank that proceeded in this manner, he chose Živnostenská Banka, on which we have focused in this study. Under the item of consortium participations in 1928, Živnostenská Banka only showed a round figure of 160 million crowns, and Pimper noted in this context that “it is known to insider circles that the actual figure of Živnostenská Banka’s participation must be disproportionately larger.”48 It is archivally documented that Živnostenská Banka maintained double balance sheet, an official one for the public and for review bodies, and a real one (which gave more accurate figures concerning the values of its assets) for internal use.

Table 2. Consortium/syndicate participation in the balance sheet of Živnostenská Banka by year (1921–1937), rounded to the nearest thousand crowns

|

Consortium/syndicate participation |

Total balance sheet assets |

Share of consortium/syndicate participation in total assets |

|

|

1921 |

21,790 |

5,269,744 |

0.41 percent |

|

1922 |

26,790 |

4,845,008 |

0.55 percent |

|

1923 |

51,745 |

4,907,020 |

1.05 percent |

|

1924 |

51,758 |

4,588,810 |

1.13 percent |

|

1925 |

50,025 |

4,597,858 |

1.09 percent |

|

1926 |

150,000 |

4,888,009 |

3.07 percent |

|

1927 |

160,000 |

5,040,327 |

3.17 percent |

|

1928 |

190,000 |

5,296,753 |

3.59 percent |

|

1929 |

217,000 |

5,675,660 |

3.82 percent |

|

1930 |

217,000 |

5,690,956 |

3.81 percent |

|

1931 |

217,000 |

5,174,312 |

4.19 percent |

|

1932 |

217,000 |

4,923,228 |

4.41 percent |

|

1933 |

217,000 |

4,904,853 |

4.42 percent |

|

1934 |

217,000 |

5,039,139 |

4.31 percent |

|

1935 |

217,000 |

5,206,099 |

4.17 percent |

|

1936 |

217,000 |

5,250,292 |

4.13 percent |

|

1937 |

217,000 |

5,362,328 |

4.05 percent |

|

Source: Compass. Finanzielles Jahrbuch Tschechoslowakei, vol. 1922–1940. |

|||

In this sense, the information on consortium/syndicate business in the balance sheet of Živnostenská Banka should be understood as indicative only, or as a “minimum figure.” However, the development trend is indisputable. In the year of establishment of the consortium department (1921), the amount of 21.79 million crowns (i.e. 0.41 percent of the balance sheet total) is stated, which gradually increased in the 1920s. In 1925, consortium/syndicate transactions amounted to 50.03 million crowns. Starting in 1926, the bank began to present a rounded figure, and from 1929, it was a fixed sum of 217 million crowns. In relation to the balance sheet total, this was approximately four percent each year (see Table 2). What the actual share of consortium transactions in the balance sheet was, however, is beyond the scope of this study and requires further research, including a detailed analysis of the bank’s books.

Conclusion

The capital market of interwar Czechoslovakia had weak links to the world market, and it would not be an exaggeration to claim that it was almost entirely isolated. At the same time, it was fragmented and very complicated, both in the segments determined by the typologies of financial institutions and in the segments of big business, where there were necessarily many conflicts of interest between firms and especially between financial institutions. The intense competition in a relatively small market reached a critical stage where competitive tensions in predefined areas were declining in favor of a significant new type of cooperation. This brought cost reductions and greater efficiency. Thus, the crowded market of individual financial institutions led to another specific characteristic phenomenon, a paradox characteristic of Czechoslovakia, namely the formation of an unusually dense network of consortia.

In interwar Czechoslovakia, banking consortia formed one of the organizational components in the network of links and relationships in business. Consortium agreements were used to launch interest groups/partnerships, which were initially related to the issuing activities of banks but were subsequently applied in new contexts, especially in connection with the implementation of projects with large credit frameworks and also with efforts to coordinate the actions of interest groups within a firm or company. This was a win-win instrument for both banks and companies. Consortia allowed banks to participate in operations and transactions that would have been unaffordable or too risky for an individual bank. They were, thus, a tool to bridge market fragmentation. Consortia supported existing close links in the capital market (coalitions of friendly banks) and sometimes acted as a catalyst, opening up possibilities for otherwise unthinkable links (cooperation among domestic German and domestic Czech banks).

In relation to the company, which was the subject of the consortium agreement, the consortium represented a tool for a stronger anchoring or multiplication of banking influence. In exchange for increased bank influence or reduced freedom of strategic decision-making, the firm increased the prospects for placing its shares on the market, gained stability in terms of financing, and, in the case of a consortial credit, achieved the necessary framework for operations and investments. Moreover, the consortium’s recovery of debts was often reported to have been more benevolent than in a bilateral relationship.49 The economic scope of consortium agreements in interwar Czechoslovakia, especially from the 1930s onwards, grew to such an extent that it can be said to have been an important market instrument which regulated and sometimes even monopolized entire industries. Each individual consortium agreement was to a large extent specific in its motivations, parameters, and consequences and must therefore be examined on its own. There can be no doubt, however, that the significance of bank consortium agreements cannot be measured by their statistical share in the transactions of each bank alone but rather must be assessed in the context of the growth of its influence in the cartelized sectors of the economy, the increase in trade guarantees, the increase in the volume of transactions, the tighter binding of companies, etc. Consortium transactions were an expression of the gradual modernization of the capital market, including its concentration, unification, and tendencies towards monopolization.

Archival Sources

Archiv České národní banky [Archive of Czech National Bank] Prague (AČNB)

Fund Živnostenská banka [Trades Bank] (ŽB)

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Československé banky v roce 1922. Statistika ministerstva financí o obchodní činnosti bank podle účetních zpráv k 31. prosinci 1922 [Czechoslovak banks in 1922. Statistics of the Ministry of Finance on the business activity of banks according to accounting reports as of December 31, 1922]. Prague: Ministerstvo financí, 1924.

Compass. Finanzielles Jahrbuch Tschechoslowakei. Vols. 1922–1940.

Ottův slovník naučný [Otto’s encyclopedia]. 24 vols. Prague: Jan Otto, 1906.

Statistická příručka republiky Československé [Statistical handbook of the Czechoslovak Republic]. Vol. 4. Prague: Státní úřad statistický 1932.

Všeobecný zákonník obchodní ze dne 17. prosince 1862 se zákonem úvodním doplněn všemi zákony a nařízeními naň se vztahujícími: ku potřebě obchodníků a obchodních škol [The General Commercial Code of December 17, 1862, with the Introductory Act, supplemented by all the laws and regulations relating thereto: for the use of traders and commercial schools]. Písek: Jaroslav Burian, 1900.

Secondary Literature

Balcar, Jaromír. Tanky pro Hitlera, traktory pro Stalina: Velké podniky v Čechách a na Moravě 1938–1950 [Tanks for Hitler, tractors for Stalin: Large enterprises in Bohemia and Moravia 1938–1950].Prague: Academia, 2022.

Bull, John. “O slávě bankéřské” [On the glory of bankers]. Přítomnost 22, no. 1 (1925): 28–30.

Eichlerová, Kateřina. “Konsorcium – základní vymezení” [Consortium – basic definition]. In Rekodifikace obchodního práva – pět let poté: Pocta Ireně Pelikánové [Recodification of commercial law – five years on: Tribute to Irena Pelikánová], vol. 2, 461–66. Prague: Wolters Kluwer, 2019.

Fousek, František. Příručka ku čtení bursovních a obchodních zpráv v denním tisku [A guide to reading stock exchange and business news in the daily press]. Prague: Pražská akciová tiskárna, 1922.

Gruber, Josef. Hospodářská organisace úvěru [Economic organization of credit]. [Prague]: Všehrd, 1920.

Heyd, Oskar Ferdinand. Repetitorium obchodních bank: Nauka o podniku, obchodní nauka, kupecká aritmetika, účetnictví, obchodní korespondence [Repetitorium of commercial banks: The science of business, business science, merchant arithmetic, accounting, business correspondence]. Prague: Československá grafická unie a.s., 1936.

Jančík, Drahomír, and Eduard Kubů, eds. Nacionalismus zvaný hospodářský: střety a zápasy o nacionální emancipaci/převahu v českých zemích (1859–1945) [Nationalism called economic: conflicts and struggles for national emancipation/superiority in the Bohemian lands, 1859–1945]. Prague: Dokořán, 2011.

Karásek, Karel et al. Obchodník ve styku s bankou čili Výhody a služby, jež poskytuje banka obchodu a průmyslu a všem činitelům národohospodářsky činným [Businessman in dealings with the bank or benefits and services provided by the bank to trade and industry and to all the agents of the national economy]. Prague: Merkur, 1925.

Klier, Čeněk. Veřejné peněžnictví [Public money system]. Prague: Česká grafická unie, 1925.

Koloušek, Jan. Národní hospodářství [National economy]. Vol. 3. Prague: Česká matice technická, 1921.

Kubů, Eduard. “Za sjednocenou nacionálně českou bankovní frontu: Založení Svazu českých bank a jeho činnost v období rakousko-uherské monarchie” [For a united national Czech banking front: Founding of the Association of Czech Banks and its activities during the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy]. Z dějin českého bankovnictví v 19. a 20. století [From the history of Czech banking in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries]. Acta Universitatis Carolinae. Philosophica et historica. Studia historica XLVII, no. 5 (1997): 139–61.

Kubů, Eduard, and Jiří Šouša. “Die Nostrifizierung von Industrie- und Handelsfirmen in der Zwischenkriegs-Tschechoslowakei: Nationale Dimension und langfristige Auswirkungen.” In Eigentumsregime und Eigentumskonflikte im 20. Jahrhundert, edited by Dieter Gosewinkel, Roman Holec, and Miloš Řezník, 45–77. Essen: Klartext Verlag, 2018.

Kunert, Jakub. “Cesta ke koruně – Půjčka národní svobody.” Parlamentní listy [Parliamentary Papers]. December 4, 2018. Last accessed on December 29, 2023. https://www.parlamentnilisty.cz/arena/nazory-a-petice/Jakub-Kunert-Cesta-ke-korune-Pujcka-Narodni-svobody-561892

Kunert, Jakub. “Průmysl a banky: Archiv České národní banky jako fundament pro výzkum historie českého a československého průmyslu 19. a 20. století” [Industry and banks: Czech National Bank Archives as a foundation for research on the history of Czech and Czechoslovak industry in the 19th and 20th centuries]. In Průmysl – město – archiv. Archivy a dokumentace průmyslového dědictví [Industry – city – archive. Archives and documentation of industrial heritage], 125–50. Prague: Česká archivní společnost, 2013.

Nečas, Ctibor. “Organizační síť a obchodní činnost českých bank v jihovýchodní Evropě (ve čtvrtstoletí před rokem 1918)” [Organisational network and business activities of Czech banks in South-Eastern Europe (in the quarter century before 1918)]. Sborník prací Filozofické fakulty brněnské university. Studia minora Facultatis Philosophicae Universitatis Brunensis 48, no. C46 (1999): 97–112.

Novotný, Jiří and Jiří Šouša. “Změny v bankovním systému v letech 1923–1938” [Changes in the banking system in 1923–1938]. In Dějiny bankovnictví v českých zemích [History of banking in the Bohemian Lands], edited by František Vencovský et al., 238–54. Prague: Bankovní institute, 1999.

Novotný, Jiří et al. “Úsilí českého finančního kapitálu o repatriaci akcií a monopolizace v lihovarském průmyslu v letech 1932–38” [Efforts of Czech finance capital to repatriate shares and monopolize the distillery industry in 1932–38]. Slezský sborník 76, no. 3 (1978): 201–10.

Pátek, Jaroslav. “Československo-rakouské kapitálové a kartelové vztahy v letech 1918–1938” [Czechoslovak-Austrian capital and cartel relations in 1918–1938]. Acta Universitatis Carolinae. Philosophica et Historica. Studia historica XL, no. 3 (1994): 127–52.

Pimper, Antonín. České obchodní banky za války a po válce: nástin vývoje z let 1914–1928 [Czech commercial banks during the war and after the war: an outline of the development from 1914 to 1928]. Prague: Zemědělské knihkupectví A. Neubert, 1929.

Pospíšil, Petr. “Emisní obchody bank” [Emission transactions of banks]. In Obchodník ve styku s bankou čili Výhody a služby, jež poskytuje banka obchodu a průmyslu a všem činitelům národohospodářsky činným [Businessman in dealings with the bank or Benefits and services provided by the bank to trade and industry and to all the agents of the national economy], edited by Karel Karásek et al., 50–54. Prague: Merkur, 1925.

Preiss, Jaroslav. Průmysl a banky: z cyklu průmyslových přednášek, ve dnech 22. až 27. dubna 1912 [Industry and banks: from a series of lectures on industry, April 22–27, 1912]. Prague: Ústav ku podpoře průmyslu, 1912.

Rosík, Bohumil. Bankovní účetnictví [Bank accounting].Prague: Otakar Janáček, 1927.

Růžička, Otakar. Organisace bank [Organization of banks]. Prague: Růžička, 1925.

Šikýř, Karel. Bankovní účetnictví [Bank accounting]. Prague: Sdružení českoslovanského úřednictva ústavů peněžních, 1913.

Slovník obchodně-technický, účetní a daňový [Business-technical, accounting and tax dictionary]. Edited by Josef Fuksa. Vol. 9. Prague: Tiskové podniky Ústředního svazu československých průmyslníků v Praze, 1937.

Špička, František. Organisace bank a technika bankovních obchodů [The organisation of banks and the technique of banking transactions]. Prague: Spolek posluchačů komerčního inženýrství, 1926.

Teichová, Alice. Mezinárodní kapitál a Československo v letech 1918–1938 [International capital and Czechoslovakia in 1918–1938]. Prague: Karolinum, 1994.

Tóth, Andrej. “K počátkům a vývoji cukrovarnického průmyslu v Uherském království do rozpadu habsburské monarchie” [On the origins and development of the sugar industry in the Kingdom of Hungary until the dissolution of the Habsburg Monarchy]. Listy cukrovarnické a řepařské 134, no. 12 (2018): 424–27.

-

1 Jančík and Kubů, Nacionalismus zvaný hospodářský, continuously in the text.

2 The so-called Nostrification Act No. 12/1920 of the Sbírka zákonů a nařízení republiky Československé [Collection of Laws and Regulations of the Czechoslovak Republic] authorized the Ministry of Industry and Trades to order companies with production plants in the Czechoslovak Republic but with their seats outside the Czechoslovak Republic to transfer their seats to the territory of the new republic. The main objective was to avoid tax losses (companies officially registered outside Czechoslovakia paid a share of their taxes to the countries in which they had their seats). However, other motives were also important. First and foremost, the act was intended to ensure the state’s influence on strategic enterprises. Nostrification was seen as one of the means of strengthening the economic independence of the new state. The nostrification process became a welcome opportunity to increase the economic influence of Czechoslovak banks, especially the national Czech banks, which took over the lending of nostrified companies. In total, over 200 large companies were nostrified with state assistance.

3 Kubů and Šouša, “Die Nostrifizierung von Industrie- und Handelsfirmen.”

4 Kubů, “Za sjednocenou nacionálně českou bankovní frontu.”

5 Všeobecný zákonník obchodní, 117–18.

6 Ottův obchodní slovník, vol. 2, 1045; Slovník obchodně-technický, účetní a daňový, vol. 9, 1402–4; Heyd, Repetitorium obchodních bank, 16–17, 127. See also Eichlerová, “Konsorcium.”

7 Pospíšil, “Emisní obchody bank,” 50–51; Růžička, Organisace bank, 100.

8 Ottův slovník naučný, vol. 24, 25.

9 Koloušek, Národní hospodářství, vol. 3, 40.

10 Kunert, “Průmysl a banky,” 137–44.

11 Rosík, Bankovní účetnictví, 248–69. For variations of accounting methods, see in detail Slovník obchodně-technický, účetní a daňový, vol. 9, 522–64.

12 Rosík, Bankovní účetnictví, 183.

13 Novotný and Šouša, “Změny v bankovním systému,” 245–46.

14 On consortia in the context of banks’ emission operations, see Pospíšil, “Emisní obchody bank,” 50–54; Rosík, Bankovní účetnictví, 263–68; Gruber, Hospodářská organisace úvěru, 26; Fousek, Příručka ku čtení bursovních a obchodních zpráv v denním tisku, 27.

15 Šikýř, Bankovní účetnictví, 58–59.

16 Ibid.

17 Nečas, “Organizační síť a obchodní činnost českých bank”; Tóth, “K počátkům a vývoji cukrovarnického průmyslu.”

18 AČNB, fund ŽB, sign. ŽB/154/1, Sale consortium of Solo shares, contract dated October 25.

19 Rosík, Bankovní účetnictví, 263–68; Slovník obchodně-technický, účetní a daňový, vol. 9, 554–64.

20 Kunert, “Cesta ke koruně.”

21 When the consortium agreement was signed, Bedřich Fuchs was the owner of a private banking house and a speculator who had significant influence in the informal background of the Prague Stock Exchange (trading also in less frequently traded stocks), and from this point of view, he was a welcome partner who could help influence the exchange rate. The press of the time referred to him as “the master of the Prague Stock Exchange.” Bull, “O slávě bankéřské.”

22 These included shares in Škoda Works, Česká společnost pro průmysl cukerní (Bohemian Sugar Industry Company), Česká obchodní společnost (Bohemian Trading Company), Rakovnické a poštorenské keramické závody a.s. (ceramic factories in Rakovník and Unter-Themenau, Ltd.), Západočeské továrny kaolinové a šamotové a.s. (West-Bohemian Kaolin and Chamotte Factories, Co. Ltd.), Breitfeld-Daněk (engineering works Breitfeld-Daněk), Českomoravské elektrotechnické závody Fr. Křižík, a. s. (Bohemian-Moravian Electrotechnical Works), Spojené továrny hospodářských strojů Fr. Melichar-Umrath a spol., a.s. (United Factories of Agricultural Machinery Fr. Melichar-Umrath and Co., Ltd.), etc. For detailed documentation on the consortium, see AČNB, fund ŽB, sign. ŽB/183/2, folder Syndicate “B”.

23 Špička, Organisace bank, 377–79.

24 Karásek et al., Obchodník ve styku s bankou, 89–90; Špička, Organisace bank, 377–78; Preiss, Průmysl a banky, 9–10.

25 AČNB, fund ŽB, sign. ŽB/178/1, convolut of documents – Radlická mlékárna syndicate.

26 Ibid., syndicate agreement of June 28, 1935.

27 Ibid.

28 Balcar, Tanky pro Hitlera, 38–39; Teichová, Mezinárodní kapitál a Československo, 89.

29 AČNB, fund ŽB, sign. ŽB/ 49-10, convolut of documents (Philips syndicate).

30 Ibid., Gedenkprotokoll aufgenommen am 3. Februar 1937 in den Lokalitäten der Živnostenská Banka in Prag über den Abschluss eines Syndikatsvertrages.

31 Ibid.

32 For a transcript of the agreement, see AČNB, fund ŽB, sign. ŽB/665/2, syndicate agreement “Czech Distillery Syndicate” of December 15, 1932 with amendments of October 23, 1936.

33 Pátek, “Československo-rakouské kapitálové a kartelové vztahy,” 137–40; Novotný et al., “Úsilí českého finančního kapitálu.”

34 For a collection of documents on the activities of the distillery consortium, see AČNB, fund ŽB, sign. ŽB/32/1, Rules of Procedure for Companies Included in the Action Distillery Syndicate; Organizational Rules for Companies Controlled by the Action Distillery Syndicate.

35 In the case of the aforementioned Radlice consortium, previously concluded parameters regarding the business and credit connections were addressed in the agreement. AČNB, fund ŽB, sign. ŽB/178/1, syndicate agreement of June 28, 1935.

36 AČNB, fund ŽB, sign. ŽB/150/1, draft agreement (1937).

37 Ibid., sign. ŽB/3959/1, list of consortium companies (undated).

38 Ibid., sign. ŽB/398/1, undated scheme of the structure of Živnostenská Banka.

39 For a detailed explanation, see ibid., sign. ŽB/3959/1, Technique of conducting consortium transactions (undated typescript).

40 Ibid., list of consortium companies (undated).

41 AČNB, fund ŽB, sign. ŽB/103/1, minutes of the meeting on November 7, 1919.

42 For a detailed overview of the participation key, see Novotný and Šouša, “Změny v bankovním systému,” 248.

43 Rosík, Bankovní účetnictví, 206–9, 213, 218.

44 Klier, Veřejné peněžnictví, 218–19.

45 Československé banky v roce 1922, 94.

46 Statistická příručka republiky Československé, vol. 4, 260.

47 Pimper, České obchodní banky, 459–60.

48 Ibid., 460.

49 Novotný and Šouša, “Změny v bankovním systému,” 245–46.

* The study was carried out under the Cooperatio program, provided by Charles University, History, at the Faculty of Arts. The text is a revised version of the chapter “V napětí konkurence a spolupráce. Bankovní konsorcia/syndikáty v meziválečném Československu (angažmá Živnostenské banky)” [In the tension of competition and cooperation. Banking consortia/syndicates in interwar Czechoslovakia (Engagement of Živnostenská Banka)] published in the collective monograph Miloš Hořejš, Eduard Kubů, Barbora Štolleová, eds., Podnikatel versus kapitál – kapitál versus podnikatel. Dvě tváře jednoho vztahu ve střední Evropě 19. a 20. století [Entrepreneur versus capital – Capital versus entrepreneur. In the tensions of competition and cooperation], Prague: NTM, 2023, 100–14.