The Share of Tithe Paid to Parish Priests in Sixteenth-Century Transylvania:  A Topographical Approach*

A Topographical Approach*

Géza Hegyi

Transylvanian Museum Society; HUN-REN Research Centre for the Humanities

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Hungarian Historical Review Volume 13 Issue 3 (2024): 403-430 DOI 10.38145/2024.3.403

The most important source of income for the medieval Latin Church, the tithes paid by lay people from their crops and livestock, was divided between several levels of the ecclesiastical hierarchy. The set of beneficiaries varied from one country or diocese to another, while the proportions essentially from one locality to another. In the Transylvanian diocese, the bishop (or the chapter) got the substantial part of the tithe (half to three quarters), while the archdeacon, as regional magistrate, uniformly received a quarter. Despite the canon law standards, in many cases only a fraction of the quarta remained to supply the parish priest. On the other hand, the parish priests from the deaneries of royal Saxons (i. e. German settlers) could usually keep the full tithe.

The aim of my research is to reconstruct the share of tithe of the Transylvanian parish clergy by locality, to map it and to analyze the spatial inequalities thus revealed. Due to the unilateral source endowments, we have only a few direct data on this, so I calculated indirectly the size and proportion of the priestly share, based on the data of a list from 1589, which only gives the local rents of the bishops and the archdeacons’ share of tithe. According to my results, the inhabitants of 1239 localities paid tithes in mid-sixteenth century Transylvania. For 457 settlements (mostly in the Székely Land) we do not know the share of the priest. In the known cases, the three most common distributions were when the local priest received no tithe (35%), a quarter of the tithe (36%) or the whole tithe (25%). The spatial distribution of the parishes with quarta was not uniform, but rather concentrated in some small areas due to various historical reasons. The level of priestly share correlated with secular and ecclesiastical privileges, the ethnicity of the population that paid the tithe, and the person of the landlord.

These results can provide important aspects for the interpretation of sources based on priestly income, such as the papal tithe register of 1332–1336, fundamental to the history of medieval Transylvania.

Keywords: Transylvania, tithe, parish priest, distribution, quarta, Saxons

Introduction

As any historian of feudal institutions knows, the practice of tithing is rooted in the regulations of the Old Testament.1 Early Christianity was still averse to it, but in the fourth and fifth centuries the idea of tithing began to become increasingly accepted. In Latin-rite territories, from the Carolingian period onwards, the tithe became a compulsory ecclesiastical annuity paid by all members of the fold. This was, of course, achieved with the support of the reigning secular power.2 Theoretically, the tithe should have been paid on all kinds of income, but due to the socio-economic conditions of the Middle Ages and the early modern period, it was collected primarily from the annual wine and grain harvests and secondarily from the reproduction of certain domestic animals (for instance sheep and bees).3 For this reason, the tithe records (documents, accounts, receipts, etc.) are an important source for the study of the rural history of Western and Central Europe.4

According to the Church Fathers (and to the canon law that quotes them), one of the functions of (and thus justifications of) tithing is to acknowledge God’s rule (signum dominii) and one is to provide support for the poor and others in need (tributum egentium animarum). The argument for a fitting tribute to the clergy (as a spiritual elite) emerges rather rarely and relatively late.5 Whatever the reason for this, the Church had always been considered the administrator and thus the actual holder of the tithe. Its exclusive right to this income was confirmed by several papal decrees and synods of the eleventh–thirteenth centuries against secular bodies of power.6 Not without reason: the tithe was by far the most important source of revenues for the Church, accounting for up to three quarters of a bishop’s income.7

The income from the tithe was divided among different actors in the ecclesiastical hierarchy. As the bishoprics were the first rank to be established in the early church and in the newly Christianized areas, the bishops themselves usually received the greater part of the tithes. Over time, tithing rights were granted to the chapters and their members, monastic convents, altar foundations, etc.8 From the outset, however, it was clear that the local priests were also entitled to a share (pars condigna) of the tithe from their parishes. The most commonly used principle in this respect was laid down by Pope Gelasius I (492–496), whose provisions were applied to the matter of tithing from the eighth century onwards. According to him, church revenues were to be divided into four parts, one of which (a quarta) was to go to the diocesan bishop, another to the parish priest, a third to the maintenance of the church (fabrica), and a fourth to charity.9 In practice, however, the set of beneficiaries varied from one diocese to another, and the proportions differed essentially from one locality to another. For example, in the areas that converted to Christianity between the eighth and eleventh centuries, the bishops generally received a much larger slice, and the local clergy received little more than metaphorical crumbs.10 However, the higher magistrates, such as the archbishop or the pope, usually did not receive a share of the tithes of other bishops’ dioceses (only from their own dioceses). The so-called “papal tithe,” which was decreed by the Second Council of Lyon (1274) and then by the Council of Vienne (1311–1312), was a different kind of tax. It obliged all ecclesiastics to pay a tithe of their income to the papal court for six years.11

In order to interpret the sources regarding the tithing, it is essential to map the local distribution of this income among the different ecclesiastical actors, since individual tithe data usually refer only to the share of one of the beneficiaries. A demographic or economic-historical evaluation12 of the papal tithe registers of 1332–1337,13 crucial to any overview of the topography and incomes of the Hungarian Church, is only possible if we know the multipliers that can be applied to the amounts paid by a priest, as this information is essential if we seek to use these amounts to calculate the total production of his parish in a given year. I have recently completed this work on parishes in mid-sixteenth century Transylvania, and I present my findings below. Essentially, I seek to identify the external factors that shaped the observed regional differences.

The Structural Framework of Tithing in Transylvania

Historical Transylvania was the eastern province of the Hungarian Kingdom in the Middle Ages, but in the mid-sixteenth century, it became the core territory of an independent principality. In terms of secular administration, it was divided into three major parts. First, there were the seven counties covering the western, northern, and central areas, which were inhabited by serfs and nobles. The feudal system in these regions differed from the average Hungarian system only in minor details. The so-called King’s Land (Königsboden, Fundus Regius), which was inhabited by privileged Saxons (i.e. German settlers), was the second area, and the Székely Land in the east was the third. The Saxons formed a comparatively urban, literate society, while the Székelys were a closed ethnic group governed by oral tradition. The Romanian population, which for the most part followed the Orthodox rite, did not have its own administrative units and lived largely in the mountainous parts of the counties and the Saxon territories.14

From the ecclesiastical point of view, most of Transylvania fell under the jurisdiction of the bishop of Transylvania, who had his seat in Gyulafehérvár (Alba Iulia/Weissenburg)15 and whose authority extended north-westwards beyond the Meszes (Meseş) Mountains, and up to the Tisza River.16 The southern part of the King’s Land (the area around Szeben [Sibiu/Hermannstadt] and Brassó [Braşov/Kronstadt]) was under the direct jurisdiction of the archbishop of Esztergom. A small region, the so-called Kalotaszeg, which is roughly the area surrounding the headwaters of the Sebes-Körös [Crişul Repede] River), belonged to the diocese of Várad (Oradea), while the region of the Lápos Basin (Ţara Lăpuşului) formed a part of the diocese of Eger.17

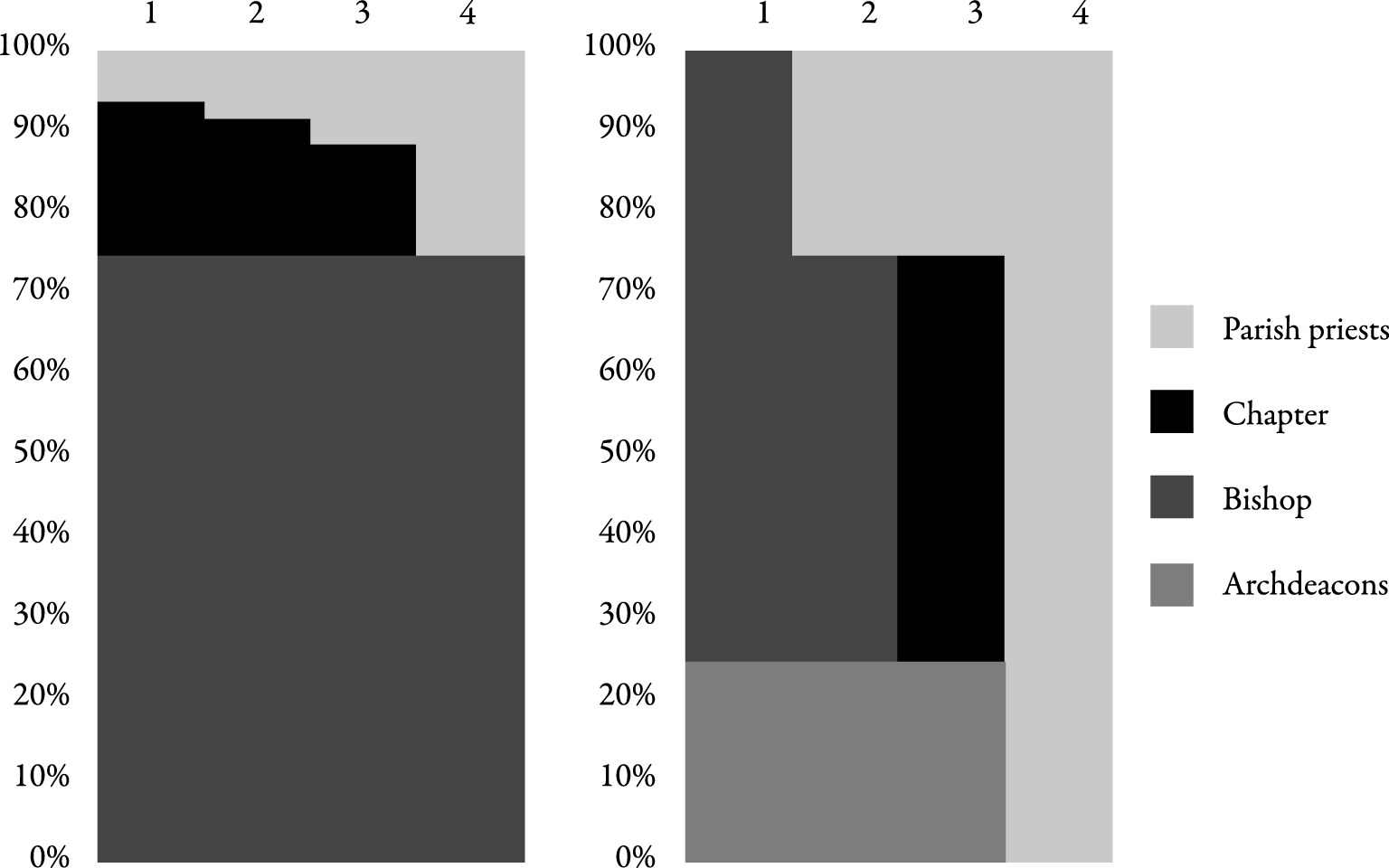

Figure 1. The old (Veszprém) and the new (Transylvania) model of distribution of the tithe.

On the question of the distribution of the tithes among the holders in Hungary, the secondary literature is unanimous in stating that three quarters of the tithe went to the diocesan bishop in each settlement, while the remaining quarter (quarta) was shared in various proportions between the cathedral chapter and the local parish priest. The latter’s share is usually estimated at a quarter of a quarta, i.e. one sixteenth of the tithe.18

The model above (see Fig. 1), however, is based solely on a few thirteenth-century papal and royal documents concerning the distribution of the tithe, as well as on a detailed examination of the tithing system of the diocese of Veszprém.19 Although it does seem to be valid for some other dioceses, too (e.g. Győr, and Várad), I believe that the general application of this model to the whole kingdom was done rather hastily in the earlier secondary literature. Based on my study of primary sources, a different system seems to have prevailed in Transylvania and in the dioceses of Eger and Zágráb. In these territories, the bishop (or the chapter) was entitled to the major share of the local tithe, which varied between half and three quarters, depending on the parish priest’s share. The archdeacon, as regional magistrate, uniformly received one quarter in his own district.20 In conclusion, the crucial difference between the previous model and the present one is that here the parish priest did not share a quarter of the tithe with the canons. Rather, he shared three quarters of the tithe with the bishop or with the chapter or, sometimes, with other beneficiaries (such as the abbot of the Kolozsmonostor Convent, altar directors, etc.).21 On the other hand, the parish priests of Saxon deaneries on the so-called King’s Land could usually keep the full tithe (libera decima).22

Sources and Methods

The 447 surviving sources of which I am currently aware on the medieval history of the tithe in Transylvania (up to 1556)23 relate mostly to the tithing affairs of the bishop and the chapter, as well as of the Saxon clergy. There is, at the same time, disappointingly little data on the tithing income of Hungarian priests in the counties.24 With these data alone, it would be impossible to reconstruct the topography of the clergy’s tithe share.

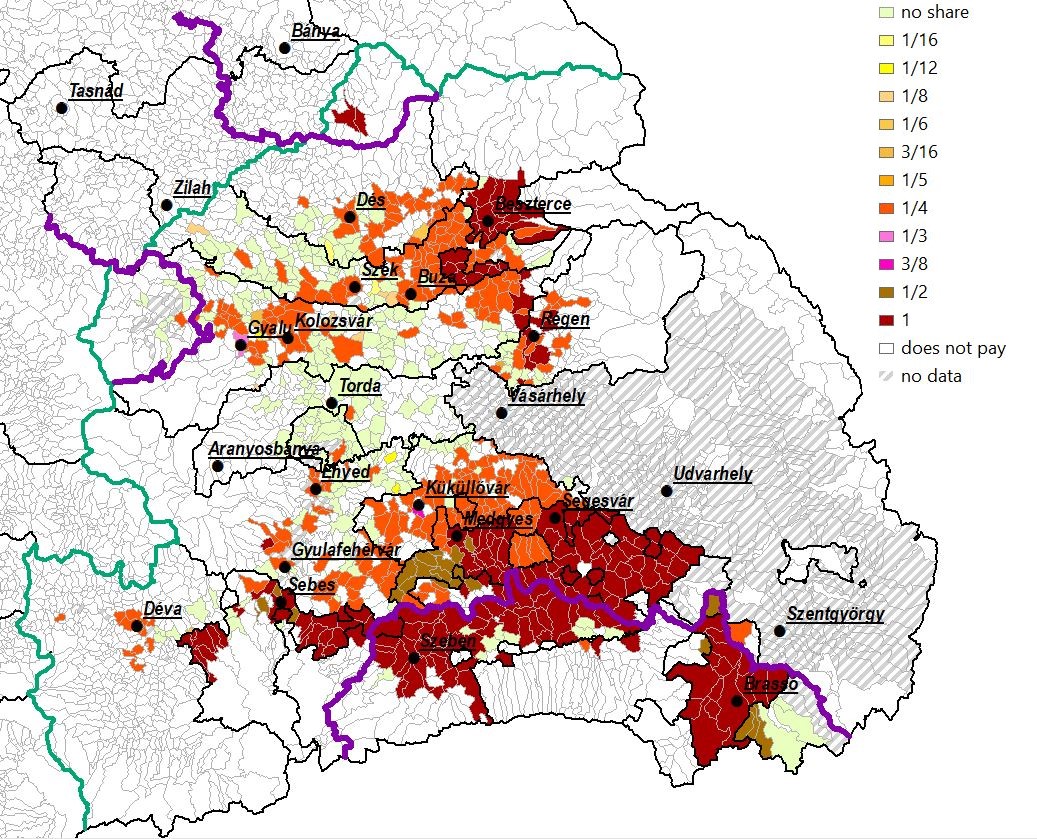

Figure 2. Transylvanian dioceses with the share of priests

However, a somewhat later but comprehensive document allows us to arrive at this reconstruction through an indirect procedure. An inventory from 1589 shows the price for which the episcopal (E) and the archdeaconal (A) tithes were rented out to local landlords in each tithe-paying settlement of the seven counties.25 These parts of the tithes were secularized in 1556, that is, confiscated to provide the material basis for the nascent principality, and from then on, they were administered by the princely treasury.26 We are not so much interested in the specific amounts as in their relative proportions, which remained largely unchanged for decades (if not centuries). A fragment of a similarly structured list from 1563 covering some parts of Küküllő and Fehér Counties, can be used as a reference, and its data are in most cases identical to those from 1589.27

As mentioned above, these two lists do not include the precise wages corresponding to the tithe of the priest (P). We have seen, however, that in most places the archdeacon’s share (A) was a quarter of the total tithe (T), so we can calculate the priest’s share, too, as follows:

T = 4A

P = T–E–A = 4A–E–A = 3A–E

And the share itself is: p = P/T

It is true that, in some cases, this method does not lead to meaningful results, for example because the share of the archdeaconry is missing28 or its quadruple does not reach the sum of the rents.29 But we cannot expect structural regularities to be applied mechanically, especially not in the medieval world. In such cases, other, individual approaches or estimates yield results. Nevertheless, the method outlined above produces acceptable proportions in the vast majority of cases, and this indirectly supports its validity. When the value of the quarta30 is also explicitly referred to in any of the registers of 1563 and 1589 (for 104 localities), there is a direct way of checking the correctness of our calculations, and the result is generally reassuring (see Table 1).

Where possible, I have also used early modern urbaria and ecclesiastical sources, which usually confirm the data of the 1589 register.31

Evaluation of the Findings

I have identified a total of 1239 tithe-paying settlements in the territory of historical Transylvania, where a total of approximately 2150 settlements existed in the mid-sixteenth century. It can therefore be concluded that about 900 settlements did not pay tithes. Typically, these were settlements where the population for a long time (often from the moment they had been founded) had been predominantly Orthodox Romanians. Tithing as a compulsory ecclesiastical tax did not exist in Eastern Christianity, and this custom was respected by the Hungarian ecclesiastical and secular authorities.32 Settlements which had been inhabited by Catholics who were later replaced by Romanians were, in principle, treated differently. In 1408, a decree stipulated that these settlements were still obliged to pay the tithe to the Catholic Church.33 However, despite its repeated renewal, in many cases the decree was not enforced,34 which explains why among the 900 villages without tithe there were several, especially in the Székás area (Podişul Secaş) of Fehér County, that lost their former Catholic Saxon population only after the Turkish invasions of the fifteenth century35 and later became Romanian.36

In addition to the Romanian villages, a few other localities were exempted from tithing. Three of these localities were mining towns in the mountains, which had predominantly Saxon (and partly Hungarian) populations,37 presumably with infertile lands, where grains and grapes, the main base for tithes, were not grown. Some Hungarian villages with Catholic parishes in Hunyad County38 also did not pay the tithe, presumably because their inhabitants were all minor nobles and were not obliged to pay taxes.

For more than a third (457) of the 1239 settlements that did pay the tithe it is not possible to determine (or even to estimate) the amount of the priestly tithe. The vast majority of these settlements (417) were found in the Székely Land, because for this territory (except for the Aranyos Seat), as a consequence of low literacy rates, we have no usable medieval or early modern data on the tithe incomes of the clergy, not only from the Middle Ages but also from the early modern period. There is only some general evidence that this privileged but poor, partly mountain dwelling population did pay the tithe.39 In the case of Kalotaszeg and the Maros (Mureş) Valley between Nagyenyed (Aiud/Engeten) and Gyulafehérvár, the scarcity or even complete lack of sources is also to blame for the holes in our knowledge.40

However, the 771 known cases are still representative of the situation in the counties and the Fundus Regius. The three most common types of distribution were when the local parish priest received no tithe (269.541); a quarter of the tithe (278.5), or the whole tithe (189).

As I have already mentioned, the latter option, which accounts for almost a quarter of all known cases, was almost exclusively linked to the Saxon parishes. However, it was not specific to all Saxon settlements, but only, with a few exceptions, to privileged areas on royal land.42 It was therefore determined primarily (though only in broad terms) by the existence of secular self-government and only secondarily, in the details, by the ecclesiastical administration. The priests of the deaneries of Szeben and Brassó, which were directly under Esztergom’s jurisdiction, enjoyed the same rights in this regard as the free Saxon deaneries under the jurisdiction of the bishop of Transylvania. The main reason for this was that the cornerstone of the Saxon privileges, the Andreanum of 1224, had already guaranteed the priestly libera decima.43 However, this happened at the expense of the former tithe-holders (the bishop and the chapter of Transylvania), and it was necessary to obtain their consent, which always involved the payment of a symbolic annuity (census). Only some of these agreements have survived: those of the Transylvanian chapter with the deaneries of Medgyes (1283, 1289) and Sebes (1303, 1330), and that of the bishop with the deanery of Kozd (c. 1330).44 However, similar arrangements must have been made for all of the deaneries established on the territory of the free (royal) Saxons, i.e. Szászváros (Broos), Kézd, Királya, and Beszterce.

Those parishes of the aforementioned deaneries, which were located on the territory of the counties, also enjoyed the right of “free tithing,” at least until around 1580.45 This was probably because they were originally royal estates, too, and their situation was little different from that of their fellows who later moved on to self-government. Exceptionally, the Saxon parishes of the deanery of Régen, which were entirely on the territory of the counties, were also in possession of the full tithe46 for reasons that are not yet known. Another special case in the western part of the King’s Land were the Romanian villages which were settled in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries in the neighborhood of certain Saxon villages 47 and paid the full tithe to the parish priests.48 However, two Saxon villages (Petres [Petriş/Petersdorf] from the deanery of Királya and Buzd [Buzd/Bussd] from the deanery of Medgyes) as well as the entire deanery of Selyk (Şeica/Schelk), which also belonged to the King’s Land but probably joined it with a delay, were excluded from the circle of those who kept the whole tithe. I touch on them in the discussion below.

In terms of the distribution of tithes, we find a particular diversity in the ten Hungarian serf villages under the jurisdiction of the deanery of Brassó at the end of the Middle Ages. Those which had previously been in royal hands for a long time as part of the domains of Höltövény (Hălchiu/Heltesdorf) and Törcsvár (Bran/Törzburg) castles, were allowed to retain the full tithe in the fifteenth century (or at least claimed it, as the Saxon clergy did), but later most of them were forced to cede half of it to the castellans for the maintenance of the castle.49 Only Újfalu (Satu Nou/Neudorf), which seceded from the royal estates in 1404 and later became the property of the city of Brassó (1462), was able to preserve successfully the libera decima.50 In contrast, the priests of villages permanently owned by private landlords did not receive any tithe at all.51 This state of affairs was not changed by the fact that they all ended up in the same position in secular terms, becoming parts of the domain of Törcsvár pledged to the city of Brassó in 1498.52

Compared to the three large groups referred to above, the number of parishes where the parish priest received half the tithe is small but significant (23). These parishes were also located in the King’s Land. Apart from Buzd and the abovementioned villages around Brassó, the 13 parishes of the deanery of Selyk belonged here, the Saxon population of which must have arrived sometime around 1300 and which only belatedly became part of the King’s Land, being formerly a noble estate.53 Although between 1322 and 1504 they had continued a lawsuit against the bishop for the same privileges as the other free Saxons, they did not succeed in obtaining the full tithe. They were granted only half of it by acquiring after 1357, in addition to their original quarta, the archdeaconal share of tithe.54 Three villages from the deanery of Sebes55 took a different path. During the Turkish invasions from 1438 and 1442, their populations had shrunk dramatically, and the Transylvanian chapter had gotten its hands on their tithes. When these localities were repopulated by Saxons, the chapter returned only half of the tithes to the parish priests.56

There were only two settlements in which the priest received between half and a quarter of the tithe: in Küküllővár, he received three eighths of the tithe and in Gyalu he received a third.57 None of this was merely a matter of chance. Küküllővár was in royal hands for a long time and functioned as a sub-residence of the voivodes and vice-voivodes, and Gyalu was a sub-residence of bishops.58

The set of localities with a priestly quarta was the most numerous and also the most heterogeneous. Their most significant subgroup (114) was that of Saxon deaneries falling wholly or largely within the territory of the counties, i.e. Sajó, Teke, Székás, Négyfalu (Vierdörfer), Hidegvíz, Lower and Upper Küküllő, and Szentlászló. These deaneries, which had attained only a lower degree of ecclesiastical self-government, also secured a quarter of the tithe from their ecclesiastical and secular superiors.59 Here we have to take into account the aforementioned Saxon village of Petres too, which became a member of the deanery and of the seat of Beszterce after having been a noble estate at the beginning of the fourteenth century.60

The ecclesiastical landowners (the bishop and chapter of Transylvania and the abbot of Kolozsmonostor) also consistently gave the local parish priests the canonically prescribed quarta of their own estates (for the domains of Gyalu, Enyed, and Gyulafehérvár),61 except when the identity of the ecclesiastical landlord and the tithe-holder differed.62 The monarch also set an example by granting a quarter of the tithe to the parish priests of the royal cities, salt-mining towns, and domains.63 He or the later baronial owners were responsible for the priestly quarta of the Hungarian parishes of other domains (Bálványos [Unguraş], and Csicsó [Ciceu]) and estates (Bonchida [Bonţida], and Búza [Buza], as well as the villages of the Bánfi and Dezsőfi families in Upper Valley of the Maros River).64 Some families of the middle nobility (Apafi, Bethleni, Erdélyi de Somkerék) also granted the quarter of the tithe to the priests of their Catholic estates, others only to the parish priest of the central settlement of their estate.65 The remaining dozen or so villages could receive the quarta by occasional donations, for which some documents have survived.66

Contrary to what is widely stated in the secondary literature, the number of clerical benefices, which represented a fraction of a quarter of a tithe, was extremely small in Transylvania. It is even possible that some of them are in fact the result of a calculation error, because the contemporaries rounded off the numbers for the sake of simplicity, and thus these numbers do not accurately reflect the smaller ratios. Mostly, the centers of some manors or estates can be included here (with one sixth or one eighth as the priestly share),67 as well as the Hungarian villages of the Zsuki family, where the priests uniformly received half of the quarta (i.e. one eighth of the tithe).68 The one-sixteenth share, which is considered common in the literature, occurs marginally, only five times, and exclusively in the northern part of the province.69

Almost as numerous as the places with quarta were the tithing villages where the parish priest received nothing from the tithe (more than a third of the known cases). For the most part, these settlements were the Hungarian villages of the small and middle nobles from the western bank of the Kis-Szamos (Şomeşul Mic) River, the Mezőség (Câmpia Transilvaniei), and between the Maros and Kis-Küküllő (Târnava Mică) Rivers, as well as the settlements of the Aranyos Seat (with the exception of Felvinc [Unirea]).70 Their landlords may not have had sufficient lobbying power, or more likely, they would not have looked kindly on the local priest having an income that exceeded their own.

In the late Middle Ages, demographic changes often led to changes in the structure of the local tithe. Exceptions were those villages of the Szászváros Seat, which were formerly inhabited by Saxons and then by Romanians. These villages continued to pay tithes to the parish priest of Szászváros.71 Usually, when a Catholic community in the King’s Land died out and the village was left deserted72 or was repopulated by Romanians,73 the priest’s share ceased to exist, and the full tithe was collected by the secular Saxon authorities or (in the deanery of Sebes) the chapter of Transylvania. The same processes led to similar results on Church estates, too.74 On the other hand, if the Catholic population disappeared in one of the villages lying on the territory of nobles, the result was ambiguous, depending on the attitude of the landlord and the time of the change. In some cases, the tithe continued to be paid (without the priestly part, of course),75 but in most cases, the tithe was completely abolished.76

As a result of the Reformation and the secularization of Church estates and revenues, the medieval ecclesiastical framework was shaken and ecclesiastical immunity and privileges were weakened. Under these circumstances, many communities were not able to resist the increasing pressure of secular elites to expropriate more and more of the tithes, even if their populations remained adherents of Western denominations. From 1580 onwards, the parish priests in the King’s Land had to be content with three-quarters of the tithe, as the princely power expropriated a quarta for the benefit of the treasury, first for a fee, and then from 1612 on, without payment.77 Encouraged by this, the Diet passed a resolution in 1588 stating that if there were places in the counties where the libera decima existed, the priestly share should be reduced to quarta.78 The primary victims of this provision were the parishes of the deanery of Régen, which lost a significant part (even if not always three quarters) of their tithe income from the following year onwards.79 Even more vulnerable were the settlements in which the Saxons had been replaced by Hungarians, and the parish was therefore cut off from the protective framework of the Saxon deaneries.80 Some settlements fared even worse. Some Hungarian villages between the two Küküllő Rivers81 lost the priestly quarta altogether sometime between 1563 and 1589.82

Conclusions

In conclusion, parishes which had the same share of the tithe as their incomes were geographically concentrated. The settlements which retained all or half of the tithe for their priests covered roughly the large southern and small northeastern blocs of the King’s Land. These areas were surrounded to the north, respectively to the west, and south by a wide band of settlements in which the parish had a quarter of the tithe, with addition of the wider area around Kolozsvár and, presumably, the Fehér County section of the right bank of the Maros River. In most of the rest of Catholic villages, the local priest received none of the tithes.

Another important observation is that the level of tithe sharing correlated with secular and ecclesiastical privileges, the ethnicity of the population that paid the tithe, and the person of the landlord. A high level of self-government, the existence of a deanery, the presence of a Saxon population, and ecclesiastical or royal possession were all advantages for the local priest in terms of the degree of his share from the tithe, while Hungarian villages with serf populations, owned by the petty nobility, and in particular villages which had been deserted and then repopulated by Romanian serfs were the least likely for him to enjoy any revenue from this ecclesiastical tax.

Table 1. The priest’s share of tithe in the settlements where the value of the quarta is known83

|

Name of settlement |

Page |

E |

A |

q |

T |

P |

p |

|

Fehér County |

|||||||

|

Nagylak (Noşlac) and Káptalan (Căptălan) |

21 |

[60] |

20 |

20 |

80 |

0 |

0 |

|

Szentkirály (Sâncrai) |

(f. 1r) 21 |

(36) 40.50 |

(14) 13.50 |

13.50 |

54 |

0 |

0 |

|

Bagó (Băgău) |

21 |

20 |

8 |

7 |

28 |

0 |

0 |

|

Lapád (Lopadea Nouă) |

(f. 1r) 21 |

(36) [40] |

(12) 8 |

12 |

48 |

0 |

0 |

|

Háporton (Hopârta) and Ispánlaka (Şpălnaca) |

(f. 1r) 21–22 |

8 |

(4) [4] |

(4) [3] |

(16) 12 |

(4) 0 |

(1/4) 0 |

|

Ózd (Ozd) |

(f. 1r) 22 |

30 |

10 |

(10) |

40 |

0 |

0 |

|

Herepe (Herepea) |

(f. 1r) 22 |

36 |

12 |

12 |

48 |

0 |

0 |

|

Csekelaka (Cecălaca) |

22 |

16 |

6 |

6 |

24 |

2 |

1/12 |

|

Lőrincréve (Leorinţ) |

23 |

4 |

2 |

[2] |

[8] |

q |

1/4 |

|

Forró (Fărău) |

(f. 1v) 23 |

36 |

12 |

12 |

48 |

0 |

0 |

|

Szentbenedek (Sânbenedic) |

(f. 1v) 23 |

36 |

12 |

12 |

48 |

0 |

0 |

|

Hunyad County |

|||||||

|

Rápolt (Rapoltu Mare) |

24 |

40 |

10 |

12.[50] |

50 |

0 |

0 |

|

Arany (Uroi) |

26 |

6 |

3 |

2.25 |

9 |

0 |

0 |

|

Küküllő County |

|||||||

|

Hosszúaszó (Valea Lungă) |

(f. 2v) 27 |

50 |

25 |

(25) |

100 |

25 |

1/4 |

|

Nagyekemező (Târnava) and Kisekemező (Târnăvioara) |

27 |

120 |

60 |

60 |

240 |

60 |

1/4 |

|

Bogács (Băgaciu) |

27 |

124 |

62 |

62 |

248 |

62 |

1/4 |

|

Nagykőrös (Curciu) |

27 |

72 |

36 |

36 |

144 |

36 |

1/4 |

|

Felsőbajom (Bazna) |

27 |

100 |

50 |

50 |

200 |

50 |

1/4 |

|

Szénaverős (Senereuş) |

(f. 2v) 28 |

64 |

32 |

32 |

128 |

32 |

1/4 |

|

Szentiván (Sântioana) |

29 |

32 |

16 |

16 |

64 |

16 |

1/4 |

|

Balázstelke (Blăjel) |

(f. 2v) 30 |

44 |

22 |

22 |

88 |

22 |

1/4 |

|

Ádámos (Adămuş) |

(f. 3r) 30 |

18 |

9 |

(9) |

36 |

9 |

1/4 |

|

Dombó (Dâmbău) |

(f. 3r) 30–31 |

16 |

8 |

8 |

32 |

8 |

1/4 |

|

Fületelke (Filitelnic) |

(f. 3r) 31 |

28 |

14 |

14 |

56 |

14 |

1/4 |

|

Domáld (Viişoara) |

(f. 3r) 31 |

16 |

8 |

8 |

32 |

8 |

1/4 |

|

Királyfalva (Crăieşti) |

(f. 3r) 31 |

32 |

16 |

(16) |

64 |

16 |

1/4 |

|

Ernye (Ernea) |

(f. 3v) 32 |

14 |

7 |

(7) |

28 |

7 |

1/4 |

|

Mikeszásza (Micăsasa) |

(f. 3v) 32 |

(13.33) 12 |

(6.67) 8* |

6.67 |

26.67 |

6.67 |

1/4 |

|

Désfalva (Deaj) |

(f. 4r) 33 |

14 |

7 |

7 |

28 |

7 |

1/4 |

|

Sárd (Şoard) |

34 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

4 |

1 |

1/4 |

|

Gálfalva (Găneşti) |

(f. 4r) 34 |

(20) 30 |

10 |

10 |

40 |

(10) 0 |

(1/4) 0 |

|

Kissáros (Delenii) |

34 |

36 |

12 |

12 |

48 |

0 |

0 |

|

Péterfalva (Petrisat) and Pettend (deserted) |

35 |

28 |

8 |

9 |

36 |

0 |

0 |

|

Kóródszentmárton (Coroisânmartin) |

(f. 4r) 35 |

(10) 15 |

5 |

(5*) |

20 |

(5) 0 |

(1/4) 0 |

|

Besenyő (Valea Izvoarelor) |

(f. 4r) 35 |

(16) 24 |

8 |

8 |

32 |

(8) 0 |

(1/4) 0 |

|

Harangláb (Hărănglab) |

(f. 4v) 35 |

(24) 36 |

12 |

12 |

48 |

(12) 0 |

(1/4) 0 |

|

Csapó (Cipău) and Kisfalud (deserted) |

35 |

18 |

6 |

6 |

24 |

0 |

0 |

|

Kisszőllős (Seleuş) |

(f. 4v) 36 |

(–) 36 |

18 |

(18*) 18 |

72 |

18 |

1/4 |

|

Kiskend (Chendu Mic), Nagykend (Chendu Mare) and Balavásár (Bălăuşeri) |

36 |

10 |

5 |

5 |

20 |

5 |

1/4 |

|

Szancsal (Sâncel) |

36 |

16 |

8 |

6 |

24 |

0 |

0 |

|

Doboka County |

|||||||

|

Bádok (Bădeşti) |

37 |

6 |

2 |

2 |

8 |

0 |

0 |

|

Magyarújfalu (Vultureni) |

37 |

16 |

8 |

8 |

32 |

8 |

1/4 |

|

Csomafája (Ciumăfaia) |

37 |

6 |

2 |

2 |

8 |

0 |

0 |

|

Báboc (Băbuţiu) |

38 |

6 |

2 |

2 |

8 |

0 |

0 |

|

Fodorháza (Fodora) |

38 |

6 |

2 |

2 |

8 |

0 |

0 |

|

Vajdaháza (Voivodeni) |

39 |

25 |

8.33 |

8.33 |

33.33 |

0 |

0 |

|

Hídalmás (Hida) |

39 |

20 |

4 |

6 |

24 |

0 |

0 |

|

Récsekeresztúr (Recea-Cristur) |

39 |

13 |

4.34 |

4.34 |

17.34 |

0 |

0 |

|

Páncélcseh (Panticeu) |

40 |

12 |

4 |

4 |

16 |

0 |

0 |

|

Köblös (Cubleşu Someşan) |

40 |

18 |

5.50 |

6 |

24 |

0.50 |

0 |

|

Derzse (Dârja) |

40 |

13 |

4.33 |

4.33 |

17.33 |

0 |

0 |

|

Felsőtők (Tiocu de Sus) |

40 |

20 |

6 |

6.50 |

26 |

0 |

0 |

|

Alsótők (Tiocu de Jos) |

40 |

6 |

2 |

2 |

8 |

0 |

0 |

|

Kecsetszilvás (Pruneni) |

40 |

14 |

4.66 |

4.67 |

18.66 |

0 |

0 |

|

Szava (Sava) |

42 |

16 |

5 |

5.25 |

21 |

0 |

0 |

|

Cegőtelke (Ţigău) |

42 |

16 |

8 |

8 |

32 |

8 |

1/4 |

|

Nagydevecser (Diviciorii Mari), Kisdevecser (Diviciorii Mici) |

42–43 |

26 |

13 |

13 |

52 |

13 |

1/4 |

|

Veresegyház (Strugureni) |

43 |

10 |

5 |

5 |

20 |

5 |

1/4 |

|

Szentandrás (Şieu-Sfântu) and Kajla (Caila) |

44 |

18 |

9 |

9 |

36 |

9 |

1/4 |

|

Kisbudak (Buduş) |

45 |

15 |

– |

5 |

20 |

5 |

1/4 |

|

Várhely (Orheiu Bistriţei) |

45 |

6 |

– |

1.50 |

6 |

0 |

0 |

|

Móric (Moruţ) |

46 |

40 |

20 |

20 |

80 |

20 |

1/4 |

|

Inner Szolnok County |

|||||||

|

Dés (Dej) |

47 |

12 |

6 |

6 |

24 |

6 |

1/4 |

|

Szentmargita (Sânmărghita) |

47 |

20 |

10 |

7.50 |

30 |

0 |

0 |

|

Somkerék (Şintereag) |

48 |

6 |

– |

[2] |

8 |

q |

1/4 |

|

Dengeleg (Livada) |

49 |

33 |

11 |

11 |

44 |

0 |

0 |

|

Iklódszentivány (deserted) |

50 |

6 |

2 |

2 |

8 |

0 |

0 |

|

Zápróc (Băbdiu) |

50 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

|

Kozárvár (Cuzdrioara) |

51 |

15 |

5 |

5* |

20 |

0 |

0 |

|

Péntek (Pintic) |

51 |

12 |

4 |

4 |

16 |

0 |

0 |

|

Girolt (Ghirolt) |

52 |

17 |

5.75 |

6.08 |

24.32 |

1.57 |

1/16 |

|

Kolozs County |

|||||||

|

Kolozsvár (Cluj-Napoca) |

53 |

500 |

250 |

250 |

1000 |

250 |

1/4 |

|

Gyeke (Geaca) |

53 |

12 |

4 |

4 |

16 |

0 |

0 |

|

Novaj (Năoiu) |

53 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

|

Légen (Legii) |

54 |

8 |

4 |

3 |

12 |

0 |

0 |

|

Zutor (Sutoru) |

54 |

6 |

2 |

2.67 |

10.67 |

2.67 |

1/4 |

|

Vásárhely (Dumbrava), Inaktelke (Inucu), Sztána (Stana) and Kiskapus (Căpuşu Mic) |

55 |

18 |

6 |

6 |

24 |

0 |

0 |

|

Tamásfalva (Tămaşa) |

55 |

13 |

5 |

4.50 |

18 |

0 |

0 |

|

Mócs (Mociu) |

55 |

10 |

3.34 |

3.34 |

13.34 |

0 |

0 |

|

Palatka (Pălatca) |

56 |

25 |

9 |

8.50 |

34 |

0 |

0 |

|

Fejérd (Feiurdeni) |

57 |

40 |

20 |

20 |

80 |

20 |

1/4 |

|

Méhes (Miheşu de Câmpie) |

58 |

16 |

6 |

5.50 |

22 |

0 |

0 |

|

Középlak (Cuzăplac) |

59 |

20 |

– |

5 |

20 |

0 |

0 |

|

Fűzkút (Sălcuţa) |

59 |

16 |

8 |

8 |

32 |

8 |

1/4 |

|

Vajola (Uila) |

60 |

12 |

6 |

6 |

24 |

6 |

1/4 |

|

Torda County |

|||||||

|

Szind (Sănduleşti) |

65 |

22 |

7.34 |

7.34 |

29.34 |

0 |

0 |

|

Boldoc (Bolduţ) |

65 |

8.50 |

2.48 |

2.75 |

11 |

0 |

0 |

|

Egerbegy (Viişoara) |

65 |

18.50 |

6.68 |

6.68 |

25.18 |

0 |

0 |

|

Gerend (Luncani) and |

66 |

26 |

8.68 |

8.68 |

34.68 |

0 |

0 |

|

Csanád (Pădureni) |

67 |

12 |

4 |

4 |

16 |

0 |

0 |

|

Jára (Iara de Mureş) |

69 |

12 |

4 |

4 |

16 |

0 |

0 |

Archival Sources

Archivio Apostolico Vaticano, Vatican City (AAV)

Registra Lateranensia (RegLat)

Registra Supplicationum (RegSuppl)

Registra Vaticana (RegVat)

Arhivele Naţionale ale României, Serviciul Judeţean Cluj [Romanian National Archives, Cluj County Branch], Cluj-Napoca (SJAN-CJ)

Fond familial Kornis (Fond 378) [Archive of the Kornis Family, in the Archives of the Transylvanian National Museum] (F 378)

Arhivele Naţionale ale României, Serviciul Judeţean Covasna [Romanian National Archives, Covasna County Branch], Sfântu Gheorghe (SJAN-CV)

Fond familial Gyulay [Archive of the Gyulay Family, in the Collection of the Székely National Muzeum] (F 65, 2-4)

Arhivele Naţionale ale României, Serviciul Judeţean Sibiu [Romanian National Archives, Sibiu County Branch], Sibiu (SJAN-SB)

Episcopia Bisericii Evanghelice C. A. din Transilvania (Fond 3) [Archive of the Saxon Lutheran Bishopric of Transylvania] (F 3)

Magistratul oraşului şi scanului Sibiu (Fond 1) [Archive of Saxon Nation and of City of Sibiu] (F 1)

Biblioteca Naţională a României, Biblioteca Batthyaneum [Romanian National Library, Batthyaneum Library], Alba Iulia (Batthyaneum)

Arhiva Capitlului din Transilvania [Private Archives of the Chapter of Transylvania] (ACT)

Erdélyi Református Egyházkerület Levéltára, Kolozsvári Gyűjtőlevéltár [Archives of the Reformed Church of Transylvania, Cluj Branch] (EREK, KvGylt)

Széki Egyházmegye Levéltára [Archives of the Deanery of Sic] (B 2)

Magyar Nemzeti Levéltár Országos Levéltára [National Archives of Hungary], Budapest (MNL OL)

Diplomatikai Fényképgyűjtemény [Diplomatic Photograph Collection] (DF)

Diplomatikai Levéltár [Diplomatic Archive] (DL)

Erdélyi Fejedelmi Kancellária [Chancellery of the Transylvanian Princes] (F 1)

Gyulafehérvári Káptalan Országos Levéltára [Public Archives of the Chapter of Transylvania], Cista comitatuum (F 4)

Hunyad megyei gyűjtemény [Collection from Hunyad County] (R 391)

Sombory család levéltára [Archive of the Sombory Family] (P 1912)

Udvarhelyi Református Egyházmegye Levéltára [Archives of the Reformed Deanery of Odorheiu Secuiesc] (UhEmLt)

Héjjasfalvi egyházközség iratai [Documents of the Parish of Vânători] (B 10)

Mohai egyházközség iratai [Documents of the Parish of Grânari] (B 15)

Bibliography

Printed sources

Barabás, Samu. “Erdélyi káptalani tizedlajstromok” [Tithe registers of the Chapter of Transylvania]. Történelmi Tár [34] (1911): 401–42.

Buzogány, Dezső, Sándor Előd Ősz, and Levente Tóth, eds. A történelmi Küküllői Református Egyházmegye egyházközségeinek történeti katasztere (1648–1800) [Historical cadaster of the parishes of the old Reformed Deanery of Küküllő]. 4 vols. Fontes Rerum Ecclesiasticarum in Transylvania 1/1–4. Kolozsvár: Koinonia, 2008–2012.

CDTrans = Jakó, Zsigmond, Géza Hegyi, András W. Kovács, eds. Codex diplomaticus Transsylvaniae. Diplomata, epistolae et alia instrumenta litteraria res Transsylvanas illustrantia. Erdélyi okmánytár. Oklevelek, levelek és más írásos emlékek Erdély történetéhez. 5 vols. Publicationes Archivi Hungariae Nationalis 2: Fontes 26, 40, 47, 53, 60. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó–MNL OL–MTA BTK TTI, 1997–2021.

CIC = Friedberg,Aemilius, ed., Corpus Iuris Canonici. 2 vols. Lipsiae: B. Tauchnitz, 1879.

Diaconescu, Marius, ed. Izvoare de antroponimie şi demografie istorică: Conscripţiile cetăţii Sătmar din 1569–1570 [Sources of anthroponymy and historical demography: The Satmar Conscriptions of 1569–1570]. Cluj-Napoca: Mega, 2012.

DocRomHist C = Sabin Belu, Ioan Dani, Aurel Răduţiu, Viorica Pervain, Konrad G. Gündisch, Marionela Wolf, Adrian Rusu, Susana Andea, Lidia Gross, Adinel Dincă, eds. Documenta Romaniae Historica. C. Transilvania. 8 vols. Bucureşti: Editura Academiei, 1977–2020.

EgyhtEml = Bunyitay, V[ince], R[ajmond] Rapaics, J[ános] Karácsonyi, F[erenc] Kollányi, J[ózsef] Lukcsics, eds. Egyháztörténelmi emlékek a magyarországi hitújítás korából [Monuments of church history from the era of Reformation in Hungary]. 5 vols. Budapest: Sectio Scient. et Litt. Societatis S. Stephani, 1902–1912.

EOE = Szilágyi, Sándor, ed. Erdélyi országgyűlési emlékek: Monumenta comitialia regni Transylvaniae. 21 vols. Monumenta Hungariae Historica 3. Budapest: MTA, 1875–1898.

ErdKirKv = Fejér, Tamás, Etelka Rácz, Anikó Szász, eds. Az erdélyi fejedelmek Királyi Könyvei [Royal books of the Transylvanian princes]. 3 vols. Erdélyi Történelmi Adatok 7: 1–3. Kolozsvár: Erdélyi Múzeum-Egyesület, 2003–2005.

Jakó, Zsigmond, ed. Adatok a dézsma fejedelemségkori adminisztrációjához. Erdélyi történelmi adatok 5/2. Kolozsvár: Erdélyi Múzeum Egyesület, 1945.

Jakó, Zsigmond, ed. A gyalui vártartomány urbáriumai. Monumenta Transsilvanica. Kolozsvár: Erdélyi Tudományos Intézet, 1944.

KmJkv = Jakó, Zsigmond, ed. A kolozsmonostori konvent jegyzőkönyvei (1289–1556) [Record books of the Kolozsmonostor Convent]. 2 vols. Publicationes Archivi Hungariae Nationalis 2: Fontes 17. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, 1990.

KvOkl = Jakab, Elek, ed. Oklevéltár Kolozsvár történetéhez [Document archive for the fistory of Kolozsvár]. 2 vols. Buda–Budapest, 1870–1888.

MonAntHung = Lukács, Ladislaus, ed. Monumenta Antiquae Hungariae. 4 vols. Monumenta Historica Socetatis Iesu 101, 112, 121, 131. Romae: Institutum Historicum Societatis Iesu, 1969–1987.

RatColl = Rationes collectorum pontificorum in Hungaria. Pápai tized-szedők számadásai. 1281–1375. Monumenta Vaticana historiam regni Hungariae illustrantia 1/1. Budapest, 1887.

RechnKrsdt = Rechnungen aus dem Archiv der Stadt Kronstadt. 3 vols. Quellen zur Geschichte der Stadt Kronstadt 1–3. Kronstadt: Römer & Kramner–T. Alexi, 1886–1896.

SzOkl = Szabó, Károly, Lajos Szádeczky, and Samu Barabás, eds. Székely oklevéltár [Document archive of the Székelys]. 8 vols. Kolozsvár–Budapest: Székely Történelmi Pályadíj-alap–MTA, 1872–1934.

Ub = Zimmermann, Franz, Carl Werner, Georg Müller, Gustav Gündisch, Herta Gündisch, Konrad G. Gündisch, and Gernot Nussbächer, eds. Urkundenbuch zur Geschichte der Deutschen in Siebenbürgen. 7 vols. Hermannstadt–Bucharest: Verein für Siebenbürgische Landeskunde–Editura Academiei, 1892–1991.

Ursuţiu, Liviu, ed. Domeniul Gurghiu (1652–1706): Urbarii, inventare şi socoteli economice. Documente, istorie, mărturii. Cluj-Napoca: Argonaut, 2007.

ZsOkl = Mályusz, Elemér, Iván Borsa, Norbert C. Tóth, Tibor Neumann, Bálint Lakatos, and Gábor Mikó, eds. Zsigmondkori oklevéltár [Document archive from the era of King Sigismund]. 16 vols. Publicationes Archivi Hungariae Nationalis 2: Fontes 1, 3–4, 22, 25, 27, 32, 37, 39, 41, 43, 49, 52, 55, 59, 61. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó–MNL OL, 1951–2022.

Secondary literature

Barcsay Mihály. “A bárcai magyarságnak rövid történeti rajza” [A short history of the Hungarian population in Burzenland]. Protestáns Egyházi és Iskolai Lap 5 (1862): 1303–10, 1335–43.

Bod, Petrus. Historia Hungarorum ecclesiastica. 2 vols. Edited by L. W. E. Rauwenhoff, in collaboration with Car. Szalay. Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1888–1890.

Boyd, Catherine E. Tithes and Parishes in Medieval Italy. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1952.

Chaline, Olivier, and Marie Francoise Saudraix-Vajda. “Introduction.” Histoire, Économie et Société 42, no. 2 (2023): 4–27. doi: 10.3917/hes.232.0004.

Constable, Giles. Monastic Tithes: From Their Origins to the Twelfth Century. Cambridge: University Press, 1964.

Csizmadia, Andor. “Die rechtliche Entwicklung des Zehnten (Decima) in Ungarn.” Zeitschrift der Savigny-Stiftung für Rechtsgeschichte. Kanonistische Abteilung 61 (1975): 228–257.

Dodds, Benn. Peasants and Production in the Medieval North-East: The Evidence from Tithes, 1270–1526. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2007.

Dudziak, Jan. Dziesięcina papieska w Polsce średniowiecznej: Studium historyczno-prawne [Papal tithes in medieval Poland: A historical and legal study]. Lublin: Wydawnictwo Towarzystwa Naukowego Katolickiego Uniwersytetu Lubelskiego, 1974.

Eissfeldt, Otto, Werner Schmidt, and Adalbert Erler. “Zehnten.” In Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart, vol. 6, edited by Kurt Galling, 1877–80. Tübingen: J. C. B. Mohr, 1962.

Engel, Pál. “Probleme der historischen Demographie Ungarns in der Anjou- und Sigismundszeit.” In Historische Demographie Ungarns (896–1996), edited by Tibor Schäfer, 57–65. Studien zur Geschichte Ungarns 11. Herne: G. Schäfer, 2007.

F. Romhányi, Beatrix. “A középkori magyar plébániák és a 14. századi pápai tizedjegyzék” [The medieval Hungarian parishes and the fourteenth-century papal tithe registers]. Történelmi Szemle 61 (2019): 339–60.

F. Romhányi, Beatrix. “Plébániák és adóporták – A Magyar Királyság változásai a 13–14. század fordulóján” [Parishes and hides: The transformation of the Kingdom of Hungary around 1300]. Századok 156 (2022): 909–41.

F. Romhányi, Beatrix, Zsolt Szilágyi, and Gábor Demeter. “A Magyar Királyság regionális különbségei a pápai tizedjegyzék keletkezése idején” [Regional differences of the Kingdom of Hungary in the era of the papal tithe registers]. Magyar Gazdaságtörténeti Évkönyv 6 (2022): 17–51.

Fejérpataky, Ladislaus. “Prolegomena ad rationes collectorum pontificiorum in Hungaria.” In Rationes collectorum pontificorum in Hungaria. Pápai tized-szedők számadásai. 1281–1375, xvii–xlvii. Monumenta Vaticana historiam regni Hungariae illustrantia 1/1. Budapest, 1887.

Fügedi, Erik. A középkori Magyarország történeti demográfiája [Historical demography of medieval Hungary]. A Központi Statisztikai Hivatal Népességtudományi Kutató Intézetének történeti demográfiai füzetei. Budapest: KSH Népességtudományi Kutató Intézet, 1992.

Fügedi, Erik. “Die Wirtschaft des Erzbistums von Gran am Ende des 15. Jahrhunderts.” Acta Historica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 7 (1960): 253–95.

Gudor, Kund Botond. Az eltűnt Gyulafehérvári Református Egyházmegye és egyházi közösségei. Inquisitoria Dioceseos Alba-Carolinensis Reformatae Relatoria (1754) [The disappeared Reformed deanery of Gyulafehérvár and its parishes]. Erdélyi Egyháztörténeti Könyvek 1. Kolozsvár–Barót: Kriterion–Tortoma, 2012.

Gündisch, Gustav. “Siebenbürgen in der Türkenabwehr, 1395–1526.” Revue Roumaine d‘Histoie 13 (1974): 415–43.

Györffy, György. “Zur Frage der demographischen Wertung der päpstlichen Zehntlisten.” In Études historiques hongroises, publiées à l’occasion du XVe Congrès International des Sciences Historiques par la Commission Nationale des Historiens Hongrois, vol. 1, 61–85. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, 1980.

Györffy, György. Einwohnerzahl und Bevölkerungsdichte in Ungarn bis zum Anfang des XIV. Jahrhunderts. Studia historica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 42. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, 1960.

Hegyi, Géza. “A ‘keresztény földre’ telepedett románok tizedfizetése: az elmélettől a gyakorlatig” [The tithe paid by the Romanians settled on “Terrae Christianorum”: from theory to praxis]. Erdélyi Múzeum 82, no. 1 (2020): 24–46.

Hegyi, Géza. “A középkori erdélyi egyházmegye esperességeiről” [Deaneries of the medieval Transylvanian diocese]. In Arhitectura religioasă medievală din Transilvania. Középkori egyházi építészet Erdélyben. Medieval Ecclesiastical Architecture in Transylvania, vol. 6, edited by Péter Levente Szőcs, 355–67. Satu Mare/Szatmárnémeti: Editura Muzeului Sătmărean, 2020.

Hegyi, Géza. “A plébánia fogalma a 14. századi Erdélyben” [The term “Plebanus” in Transylvania in the 14th century]. Erdélyi Múzeum 80, no. 1 (2018): 1–29.

Hegyi, Géza. “Az egyházi tized intézményrendszerének változásai a középkori erdélyi egyházmegyében” [Changes of the system of tithing in the medieval Transylvanian diocese]. In Határon innen és túl: Gazdaságtörténeti tanulmányok a magyar középkorról, edited by István Kádas, and Boglárka Weisz, 185–229. Budapest: BTK TTI, 2021.

Hegyi, Géza. “Did Romanians Living on Church Estates in Medieval Transylvania Pay the Tithe?” Hungarian Historical Review 7 (2018): 694–717.

Hegyi, Géza. “Egyházigazgatási határok a középkori Erdélyben (I. közlemény)” [Borders of ecclesiastical administration in the medieval Transylvania. Part 1]. Erdélyi Múzeum 72, no. 3–4 (2010): 1–32.

Hegyi, Géza. “Terrae Christianorum. A ‘keresztény földre’ telepedett románok dézsmáltatásának kezdetei” [The beginning of tithing among the Romanians moved to “Terrae Christianorum” in Transylvania]. Erdélyi Múzeum 79, no. 1 (2017): 61–75.

Hegyi, Géza. “The Relation of Sălaj with Transylvania in the Middle Ages.” Annales Universitatis Apulensis. Series Historica 16, no. 2 (2012): 59–86.

Hegyi, Géza. “Transylvanie”. In Démystifier l’Europe centrale: Bohême, Hongrie et Pologne du VIIe au XVIe siècle, edited by Marie-Madeleine de Cevins, 816–20. Paris: Passés composés, 2021.

Hennig, Ernst. Die päpstlichen Zehnten aus Deutschland im Zeitalter der avignonesischen Papstums und während des Grossen Schismas. Halle: Max Niemeyer, 1909.

Holub, József. Zala megye története a középkorban [The history of Zala County in the Middle Ages]. Vol. 1. Pécs, 1929.

Jagersma, Hendrik. “The Tithes in the Old Testament.” In Remembering all the Way… A Collection of Old Testament Studies Published on the Occasion of the Fortieth Anniversary of the Oudtestamentisch Werkgezelschap in Nederland, edited by A. S. van der Woude, 116–28. Oudtestamentische Studien 21. Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1981.

Kemény, Joseph. “Bruchstück aus der Geschichte der vaterländischen geistlichen Zehnten mit besonderer Bezugnahme auf unsere Walachen.” Magazin für Geschichte, Literatur und alle Denk- und Merkwürdigkeiten Siebenbürgens 2 (1847): 381–97.

Körting, Corinna. “Zehnt. I. Altes und Neues Testament.” In Theologische Realenzyklopädie, vol. 36, edited by Gerhard Müller, Horst Balz, Gerhard Krause, 488–90. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2004.

Kristó, Gyula. A vármegyék kialakulása Magyarországon [The formation of counties in Hungary]. Nemzet és emlékezet. Budapest: Magvető, 1988.

Kristó, Gyula. Early Transylvania (895–1324). Budapest: Lucidus, 2003.

Kuujo, Erkki Olavi. Das Zehntwesen in der Erzdiözese Hamburg-Bremen bis zu seiner Privatisierung. Annales Academiae Scientiarum Fennicae. Ser. B, tom. 62, 1. Helsinki: Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia, 1949.

Lepointe, G[abriel]. “Dîme.” In Dictionnaire de Droit Canonique, vol. 4, edited by R. Naz, 1231–44. Paris-VI: Librairie Letouzey et Ané, 1949.

Le Roy Ladurie, Emmanuel, and Joseph Goy. Tithe and Agrarian History from the Fourteenth to the Nineteenth Century: An Essay in Comparative History. Cambridge University Press, 1982.

Lindner, Dominikus. “Vom mitteralterlichen Zehntwesen in der Salzburger Kirchenprovinz.” Zeitschrift der Savigny-Stiftung für Rechtsgeschichte. Kanonistische Abteilung 46 (1960): 277–302.

Loy, Georg. Der kirchliche Zehnt im Bistum Lübeck von den ersten Anfängen bis zum Jahre 1340. Preetz: J. M. Hansen, 1909.

Mályusz, Elemér. “Az egyházi tizedkizsákmányolás” [Ecclesiastical exploitation by tithe]. In Tanulmányok a parasztság történetéhez Magyarországon a 14. században, edited by György Székely, 320–33. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, 1953.

Müller, Georg. Die deutschen Landkapitel in Siebenbürgen und ihre Dechanten 1192–1848. Ein rechtsgeschichtlicher Beitrag zur Geschichte der deutschen Landeskirche in Siebenbürgen. Archiv des Vereins für Siebenbürgische Landeskunde 48. 3 vols. Hermannstadt: Verein für Siebenbürgische Landeskunde, 1934–1936.

Müller, Georg. “Die ursprüngliche Rechtslage der Rumänen im Siebenbürger Sachsenlande.” Archiv des Vereins für Siebenbürgische Landeskunde 38 (1912): 85–314.

Plöchl, Willibald. Das kirchliche Zehntwesen in Niederösterreich. Forschungen zur Landeskunde von Niederösterreich 5. Vienna: Verein für Landeskunde und Heimatschutz von Niederösterreich und Wien, 1935.

Prodan, David. Iobăgia în Transilvania în secolul al XVI-lea [Serfdom in Transylvania in the sixteenth century]. 3 vols. Bucureşti: Editura Academiei, 1967–1968.

Puza, Richard. “Zehnt. I. Allgemeine Darstellung des Kirchenzehnten.” In Lexikon des Mittelalters, vol. 9, edited by Henri Bautier, Gloria Avella-Widhalm, and Robert Auty,499–502. Munich: LexMA, 1998.

Rácz, György. “A magyarországi káptalanok és monostorok magisztrátus-joga a 13–14. században” [The magisterial right of Hungarian chapters and monasteries in the 13th–14th centuries]. Századok 134 (2000): 147–210.

Roth, Harald. Kleine Geschichte Siebenbürgens. Cologne–Weimar–Vienna: Böhlau, 1996.

Samaran, Charles, and Guillaume Mollat. La fiscalité pontificale en France au XIVe siécle (période d’Avignon et Grand Schisme d’Occident). Bibliothèque des Écoles Françaises d’Athènes et de Rome 96. Paris: Albert Fontemoing, 1905.

Solymosi, László. “Das kirchliche Mortuarium im mittelalterlichen Ungarn.” In Forschungen über Siebenbürgen und seine Nachbarn: Festschrift für Attila T. Szabó und Zsigmond Jakó, edited by Kálmán Benda, Thomas von Bogyay, Horst Glassl, and Zsolt K. Lengyel, 51–65. Studia Hungarica 31, vol. 1. Munich: R. Trofenik, 1987.

Solymosi, László. “Tized” [Tithe]. In Magyar Művelődéstörténeti Lexikon, edited by Péter Kőszeghy, vol. 12, 65–67. Budapest: Balassi, 2011.

Teutsch, Georg Daniel. Das Zehntrecht der evangelischen Landeskirche A.B. in Siebenbürgen. Schässburg: C. J. Habersang, 1858.

Vekov Károly. “A gyulafehérvári káptalan hiteleshelyi tevékenysége és 16. századi szekularizációja” [The authentication activity and the sixteenth-century secularization of the Chapter of Transylvania]. In Loca credibilia. Hiteleshelyek a középkori Magyarországon. Egyháztörténeti Tanulmányok a Pécsi Egyházmegye Történetéből 4, edited by, Tamás Fedeles, Irén Bilkei,131–41. Pécs: Fény Kft., 2009.

Viard, Paul. Histoire de la dîme ecclésiastique, principalement en France, jusqu’au décret de Gratien. Dijon: Jobard, 1909.

Vischer, Lukas. “Die Zehntforderung in der alten Kirche.” Zeitschrift für Kirchengeschichte 70 (1959): 201–17.

W. Kovács, András. “The Participation of the Medieval Transylvanian Counties in Tax Collection.” Hungarian Historical Review 7 (2018): 671–93.

Zimmermann, Gunter. “Zehnt. III. Kirchengeschichtlich.” In Theologische Realenzyklopädie, edited by Gerhard Müller, Horst Balz, and Gerhard Krause, vol. 36, 496–504. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2004.

-

1 Körting, “Zehnt”; Jagersma, “Tithes in OT”; Eissfeldt et al., “Zehnten,” 1878–79. Cf. Gen. 14:20, 28:22; Lev. 27:30–33; Num. 18:21.24–28; Deut. 12:6.11.17, 14:22–29, 26:12–26; 2 Chron. 31:5–12; Neh. 10:38–40, 12:44, 13:5.12–13; Mal. 3:8–10; Tob. 1:6–8; Matt. 23:23; Luke 11:42.

-

2 Zimmermann, “Zehnt,” 495–98; Puza, “Zehnt,” 499–500; Constable, Monastic Tithes, 13–56; Eissfeldt et al., “Zehnten,” 1879; Vischer, “Zehntforderung”; Boyd, Tithes and Parishes, 26–46; Lepointe, “Dîme,” 1231–32; Viard, Dîme, 17–148.

-

3 Zimmermann, “Zehnt,” 499–500; Puza, “Zehnt,” 500–501; Constable, Monastic Tithes, 16–19, 34–35; Eissfeldt et al., “Zehnten,” 1879; Lepointe, “Dîme,” 1232–33; Viard, Dîme, 101–5, 150–60.

-

4 Dodds, Peasants and Production; Le Roy Ladurie and Goy, Tithe and Agrarian History.

-

5 CIC, vol. 1, 784 (C. 16, q. 1, c. 66); ibid., vol. 2, 563–65, 568 (X 3.30, c. 22, 26, 33). Cf. Constable, Monastic Tithes, 10–13, 36, 43–44, 47–52; Vischer, “Zehntforderung,” 210–11, 214–16; Lepointe, “Dîme,” 1236–39; Viard, Dîme, 89–91.

-

6 CIC, vol. 1, 417–18 (C. 1, q. 3, c. 13–14), 801 (C. 16, q. 7, c. 3.); ibid., vol. 2, 561–62 (X 3.30, c. 15, 17, 19.), 1048–50 (VI 3.13, c. 2), 1062–64 (VI 3.23, c. 13). Cf. Zimmermann, “Zehnt,” 497, 498; Puza, “Zehnt,” 500; Eissfeldt et al., “Zehnten,” 1879; Lepointe, “Dîme,” 1234–35; Viard, Dîme, 205–17.

-

7 Puza, “Zehnt,” 501; Fügedi, “Wirtschaft des Erzbistums,” 258.

-

8 Constable, Monastic Tithes, 57–197; Lepointe, “Dîme,” 1234; Kuujo, “Zehentwesen in Hamburg–Bremen,” 218–41; Plöchl, “Zehentwesen in Niederösterreich,” 49–54, 89–92; Viard, Dîme, 173–75, 181–204; Loy, “Zehnt im Bistum Lübeck,” 5–9, 52–54.

-

9 Zimmermann, “Zehnt,” 497; Puza, “Zehnt,” 500; Constable, Monastic Tithes, 27–28, 35–42, 49–56; Eissfeldt et al., “Zehnten,” 1879; Boyd, Tithes and Parishes, 75–79; Lepointe, “Dîme,” 1234; Viard, Dîme, 112–24, 175–80.

-

10 Zimmermann, “Zehnt,” 497–98; Lindner, “Zehntwesen in Salzburg”; Boyd, Tithes and Parishes, 79–153, 233–34; Kuujo, “Zehentwesen in Hamburg–Bremen,” 168–91; Plöchl, “Zehentwesen in Niederösterreich,” 55–56, 84–89.

-

11 Hegyi, “Egyházigazgatási határok,” 9–17; Dudziak, Dziesięcina papieska, 56–100, 180–203; Hennig, Päpstliche Zehnten, 7–26; Samaran and Mollat, Fiscalité pontificale, 12–22; Fejérpataky, “Prolegomena,” xx–xxii, xxv–xlvii.

-

12 Cf. F. Romhányi et al., “Regionális különbségek”; F. Romhányi, “Plébániák és adóporták,” 916–27; F. Romhányi,“Középkori magyar plébániák,” 348–51; Engel, “Probleme,” 57–63; Fügedi, “Történeti demográfia,” 25–28; Györffy, “Päpstliche Zehntlisten”; Györffy, Einwohnerzahl, 29–30.

-

13 Edited in RatColl, 41–409.

-

14 Cf. Chaline and Saudraix-Vajda, “Introduction”; Hegyi, “Transylvanie”; Roth, Kleine Geschichte.

-

15 The names of the Transylvanian localities are used in their Hungarian form, as these are the names that appear in the sources. However, in the first occurrence of the place name, the current, official (Romanian) form, and, where appropriate, the historical German variants of the name are given, too, in brackets.

-

16 In the discussion below, I ignore this part of the diocese due to the lack of sources and limit my investigation to Transylvania in the secular sense.

-

17 Hegyi, “Esperességek,” 359–63; Hegyi, “Relation of Sălaj,” 62–65; Kristó, Early Transylvania, 79–84; Kristó, Vármegyék kialakulása, 426–27, 478, 482–512. Cf. RelColl 49–50, 54, 70, 76, 84, 89, 91–144, 327, 330, 355–56.

-

18 F. Romhányi, “Plébániák és adóporták,” 918 (see note 27, too); Solymosi, “Tized,” 66; Rácz, “Magisztrátus-jog,” 151, 159–60; Györffy, “Päpstliche Zehntlisten,” 64; Csizmadia, “Rechtliche Entwicklung,” 230–31; Mályusz, “Tizedkizsákmányolás,” 322.

-

19 Solymosi, “Kirchliche Mortuarium,” 52–54; Holub, Zala, vol. 1, 383–404.

-

20 1298: Ub, vol. 1, 210; 1334: ibid., vol. 1, 465; 1357: ibid., vol. 2, 146–47; 1367: DocRomHist C, vol. 13: 332; 1380: Ub, vol. 2, 528; 1394: ibid., vol. 3, 75; 1428: ibid., vol. 4, 327; 1439: AAV, RegSuppl, 357: 26r and RegLat, 367: 142v; 1451: DL 39579; 1505: DL 65194; 1509: DF 253542; 1510: SJAN-SB, F 1, 1-U5-1226; 1517: DL 82485; 1518: DF 277755; 1526: DF 253624; 1536: EgyhtEml, vol. 3, 75; 1538: ibid., vol. 3, 313; 1541: Batthyaneum, ACT, 5-41; 1550: MNL OL, P 1912, 36-1; 1552: SJAN-CJ, F 378, 1-64; 1554: Batthyaneum, ACT, 5-98.

-

21 Hegyi, “Tized intézményrendszere,” 189–94, 197–200.

-

22 Ibid., 195–97; Hegyi, “Plébánia fogalma,” 16–19; Müller, Landkapitel, 122–83; Teutsch, Zehntrecht, 18–47.

-

23 Cf. Hegyi, “Tized intézményrendszere,” 185–87.

-

24 1322: Ub, vol. 1, 368; 1398: DF 257485; 1414: ZsOkl, vol. 4, no. 1632; 1444: KmJkv, 1: no. 522; 1521: KvOkl, vol. 1, 353; 1541: Batthyaneum, ACT, 5-41. Cf. Hegyi, “Tized intézményrendszere,” 194–95; Hegyi, “Plébánia fogalma,” 14.

-

25 Edited in Jakó, Dézsma, 20–75.

-

26 EOE, vol. 2, 64–65, 74–75, 82, 97; ErdKirKv, vol. 1/1, no. 79, 138; ibid., vol. ½, no. 24, 72; ibid., vol. 1/3, no. 363, 1137. Cf. Vekov, “Hiteleshely és szekularizáció,” 135–37.

-

27 SJAN-SB, F 3, 1-173. (I am grateful to Emőke Gálfi for drawing my attention to the document.) The dating of the source is justified by the fact that it mentions the widow of Nikola Cherepovich (who died in June 1562) and notes that Gergely Apafi (who died before September 1563) was still paying the rent for the tithe in person.

-

28 FH: Bece (Beţa), Feldiód (Stremţ); KÜ: Boldogfalva (Sântămărie); DO: Kisbudak (Buduş/Budesdorf), Várhely (Orheiu Bistriţei/Burghalle); BSZ: Somkerék (Şintereag); KL: Gyalu (Gilău), Gesztrágy (Straja), Középlak (Cuzăplac). Cf. Jakó, Dézsma, 23, 29, 45, 48, 53, 58, 59. For ease of identification, I have also included the county code before each group of settlements (BSZ = Belső-Szolnok, DO = Doboka, FH = Fehér, HD = Hunyad, KL = Kolozs, KÜ = Küküllő, TD = Torda).

-

29 FH: Lapád (Lopadea Nouă); HD: Rápolt (Rapoltu Mare); KÜ: Küküllővár (Cetatea de Baltă/Kokelburg); DO: Kisesküllő (Aşchileu Mic), Mikó (disappeared), Hídalmás (Hida), Esztény (Stoiana), Olnok (Bârlea); BSZ: Monostorszeg (Mănăşturel); TD: Décse (Decea), Szengyel (Sângeru de Pădure). Cf. Jakó, Dézsma, 21, 24, 29, 38–41, 49, 67, 68.

-

30 In the register of 1589, the term quarta is always used in the absolute sense, i.e. it refers to a quarter of the total tithe. By contrast, the adjectives integra or medium referred to the portion rented (E+A).

-

31 Prodan, Iobăgia, vol. 1, 255–56, vol. 2, 568, 630; Jakó, Gyalui urbárium, 52, 53, 57, 69, 97, 100, 109, 127, 143, etc.; Ursuţiu, Gurghiu, 39, 63, 66, 76, 82–83, 103, etc. – MonAntHung, vol. 2: 99, 101, 249; 4: 284, 290; EREK, KvGylt, B 2, Prot. 1/1, p. 1–14, 519–664; Buzogány et al., Küküllői Egyházmegye, passim; Gudor, Gyulafehérvári Egyházmegye, 369–425.

-

32 Hegyi, “Did Romanians,” 694–97, 707–10.

-

33 Hegyi, “Terrae Christianorum.”

-

34 Hegyi, “Románok tizedfizetése,” 25–29, 31–32, 35–36.

-

35 Cf. Gündisch, “Türkenabwehr.”

-

36 E.g. Drassó (Draşov/Troschen), Birbó (Ghirbom/Birnbaum), Alamor (Alămor/Mildenburg). Cf. Hegyi, “Románok tizedfizetése,” 26–27, 30–31, 35.

-

37 FH: Abrudbánya (Abrud/Grossschlatten); TD: Offenbánya (Baia de Arieş/Offenberg); BSZ: Radna (Rodna/Rodenau).

-

38 Hosdát (Hăşdat), Rákosd (Răcăştia), Lozsád (Jeledinţi). For their Catholic parishes, see: 1503: DL 46764; 1524: DL 47548; 1533: MNL OL, R 391, 1-8-4.

-

39 1462: SzOkl, vol. 1,192; 1466: ibid., vol. 8, 115; 1496: Barabás, “Tizedlajstromok,” 427; 1503: SzOkl, vol. 3, 155; 1522: ibid., vol. 2, 10; 1535: SJAN-CV, F 65, 2-4-1(6).

-

40 The villages of Kalotaszeg district are listed in the tithe register of 1589, but since they were previously part of the bishopric of Várad, the distribution of the tithe was different from that of Transylvania, and therefore the share of the priests cannot be calculated in the same way as described above (cf. Jakó, Dézsma, 61–64). On the tithe-paying settlements from the valley of the Maros River: 1477: Barabás, “Tizedlajstromok,” 417; 1496: ibid., 421, 428–29; 1504: DF 277689, fol. 2v–3r, 7v–8r.

-

41 The fractional numbers appear due to the fact that the territory of some settlements was divided between two ecclesiastical units, and this might result in differences regarding the distribution of the tithe. The settlements in question are Balázsfalva (Blaj), Medgyes (Mediaş/Medwisch), Segesvár (Sighişoara/Schässburg), Kecset (Aluniş), Gyeke (Geaca), Gyerővásárhely (Dumbrava), Sztána (Stana), Almás (Almaşu), Kispetri (Petrinzel), and Bábony (Băbiu).

-

42 Hegyi, “Tized intézményrendszere,” 195–96; Hegyi, “Plébánia fogalma,” 19; Müller, Landkapitel, 123–127.

-

43 Ub, vol. 1, 34 = CDTrans, vol. 1, no. 132.

-

44 1283: Ub, vol. 1, 145 = CDTrans, vol. 1, no. 399; 1289: Ub, vol. 1, 160 = CDTrans, vol. 1, no. 445; 1303: Ub, vol. 1, 226–27 = CDTrans, vol. 2, no. 21; 1330: Ub, vol. 1, 421–26, 433–36 = CDTrans, vol. 2, nos. 618, 676–77; [c. 1330]: Ub, vol. 1, 440 = CDTrans, vol. 2, no. 688.

-

45 1543: Batthyaneum, ACT, 5-59 (Igen [Ighiu/Krapundorf]); 1560: MNL OL, F 4, Alba, 1-5-13 (Kisenyed [Sângătin/Klein-Enyed]); 1614: MNL OL, F 1, 10, p. 154 (Fogaras [Făgăraş]. I am grateful to Tamás Fejér for sending me the transcription of the source.); 1622: Kemény, “Bruchstück,” 394 (Kövesd [Coveş/Käbisch]); 1627, 1637: UhEmLt, 2/15 (Moha [Grânari/Muckendorf]); 1640: ibid., B 10, 10 (Héjjasfalva [Vânători/Diewaldsdorf]); 1642: Bod, Historia ecclesiastica, vol. 1, 280 (Bürkös [Bârghiş/Bürgisch]);1648: Kemény, “Bruchstück,” 396–97 (Réten [Retiş/Rittersdorf]). Cf. Müller, Landkapitel, 125–26, 174–75.

-

46 Jakó, Dézsma, 71–72; Müller, Landkapitel, 165–67.

-

47 Vajdej (Vaidei), Dál (Deal), Kerpenyes (Cărpiniş), Poján (Poiana Sibiului), Ród (Rod/Rodt), Guraró (Gura Râului/Auendorf).

-

48 Müller, “Rechtslage der Rumänen,” 110, 154, 156, 167–68.

-

49 Apáca (Apaţa), Krizba (Crizbav), Csernátfalu (Cernatu), perhaps even Bácsfalu (Baciu) and Türkös (Turcheş). See: 1456: Ub, vol. 5, 527, 529–30; 1506: RechnKrsdt, vol. 1, 104; 1544: Brandsch, “Dorfschulen,” 503; 1554: RechnKrsdt, vol. 3, 469. Cf. Barcsay, “Bárcai magyarság,” 1310, 1337. – Previous attempts by the castellans to expropriate a part of the tithe: 1351: CDTrans, vol. 3, nos. 618–620; 1352: ibid., vol. 3, no. 660; 1354: ibid., vol. 3, no. 772; 1355: ibid., vol. 3, no. 800; 1361: ibid., vol. 4, no. 95–96. – On the history of land tenure: 1366: DocRomHist C, vol. 13, 101–2; 1444: DL 29252; 1460: Ub, vol. 6, 85; 1476: Ub, vol. 7, 115–16; 1484: Ub, vol. 7, 369–70.

-

50 1404: Ub, vol. 3, 333; 1456: Ub, vol. 5, 528; 1462: Ub, vol. 6, 127–29, 142–43; 1471: Ub, vol. 6, 489, 493–94. Cf. Müller, Landkapitel, 137–38; Barcsay, “Bárcai magyarság,” 1341.

-

51 Hosszúfalu (Satulung), Tatrang (Tărlungeni), Zajzon (Zizin), Pürkerec (Purcăreni). See: 1367: DocRomHist C, vol. 13, 299–301; 1373: ibid., vol. 14, 398–401; 1544: Brandsch, “Dorfschulen,” 503–4. Cf. Müller, Landkapitel, 137–38; Barcsay, “Bárcai magyarság,” 1335, 1337–38.

-

52 1500: DF 247090; 1548–1555: RechnKrsdt, vol. 3, 469. Cf. W. Kovács, “Participation of the Counties,” 685–86.

-

53 In 1305, some of the villages here (Baromlak [Valea Viilor/Wurmloch], Ivánfalva [Ighişu Nou/Eibesdorf]) were still in the hands of private landlords (Ub, vol. 1, 229–30 = CDTrans, vol. 2, no. 44), and in 1322 the area is described as a “novella plantatio” (Ub, vol. 1, 369).

-

54 1322: Ub, vol. 1, 369 = CDTrans, vol. 2, no. 444; 1323: Ub, vol. 1, 376 = CDTrans, vol. 2, no. 465; 1357: Ub, vol. 2, 146–47 = CDTrans, vol. 3, no. 959; 1364: AAV, RegVat, 251: 347r-v; 1369: Ub, vol. 2, 323 = CDTrans, 4: no. 732; 1414: Ub, vol. 3, 591–92, 596–97, 600–1; 1415: Ub, vol. 3, 644–51, 662–63; 1416: ZsOkl, vol. 5, no. 1618; 1454: KmJkv, vol. 1, no. 1147; 1504: Teutsch, Zehntrecht, 132–36, DF 246275, SJAN-SB, F 1, 1-U5-1882. Cf. Müller, Landkapitel, 168–70; Teutsch, Zehntrecht, 35–38.

-

55 Szászpián (Pianu de Jos/Deutschpien) with Oláhpián (Pianu de Sus/Walachischpien), Lámkerék (Lancrăm/Langendorf), Rehó (Răhău/Reichenau).

-

56 1494: DF 245206; 1477: Barabás, “Tizedlajstromok,” 418; 1496: ibid., 420–21, 433; 1504: DF 277689, fol. 2v, 10v; 1513: DF 277731/b, fol. 1v. Cf. Müller, Landkapitel, 160–61.

-

57 1589: Jakó, Dézsma, 29 (Küküllővár); 1640: Jakó, Gyalui urbáriumok, 57; 1666: ibid., 148; 1679: ibid., 205 (Gyalu).

-

58 The bishops also provided generously for the local priests of their estates beyond Meszes Mountain: they received half the tithe in Zilah (Zalău) and a third in Tasnád (Tăşnad) (Diaconescu, Izvoare, 37, 117). In contrast, the cathedral city of Gyulafehérvár had only a parish with quarta (1754: Gudor, Gyulafehérvári Egyházmegye, 399).

-

59 Hegyi, “Plébánia fogalma,” 19; Müller, Landkapitel, 131–32, 134, 145, 151–52, 178–80; Teutsch, Zehntrecht, 32–34.

-

60 Cf. [1314?]: Ub, vol. 1, 300 = CDTrans, vol. 2, no. 218.

-

61 1414: ZsOkl, vol. 4, no. 1632; 1444: KmJkv, vol. 1, no. 522; 1580: MonAntHung, vol. 2, 99, 101 (estates of the Kolozsmonostor Convent); 1589: Jakó, Dézsma, 52–53 (bishop’s domain of Gyalu). On the chapter estates, the priests’ share of tithes can be more or less deduced from the quartas of the provost and the canons (1477: Barabás, “Tizedlajstromok,” 417–18).

-

62 E.g. FH: Kutyfalva (Cuci), Koppánd (Copand), and Nagylak (Noşlac) (cf. Jakó, Dézsma, 21–23). They were the estates of the chapter, but their tithe belonged to the bishop.

-

63 Royal city: Kolozsvár (Cluj/Klausenburg). Salt-mining towns: Dés (Dej), Désakna (Ocna Dejului), Szék (Sic), Kolozsakna (Cojocna). Torda (Turda) seems to be an exception in this respect, as the priest here received little or no tithe (cf. Hegyi, “Plébánia fogalma,” 15–16). Royal castles with their domains: Déva (Deva), Küküllővár, Görgény (Gurghiu).

-

64 On estates and their landlords see Pál Engel’s digital map of medieval Hungary (available for download here: https://abtk.hu/hirek/1713-megujult-engel-pal-adatbazisa-a-kozepkori-magyarorszag-digitalis-atlasza).

-

65 FH: Tövis (Teiuş); TD: Felvinc (Unirea), Gyéres (Câmpia Turzii), Vajdaszentivány (Voivodeni); KL: Szamosfalva (Someşeni), Fejérd (Feiurdeni); DO: Drág (Dragu), Doboka (Dăbâca).

-

66 1398: DF 257485 (Szengyel [Sângeru de Pădure, TD]); 1541: Batthyaneum, ACT, 5-41 (Solymos [Şoimuş, HD]).

-

67 One sixth: Apanagyfalu (Nuşeni, BSZ). One eighth: Léta (Liteni, KL); Magyaregregy (Românaşi, DO).

-

68 KL: Alsózsuk (Jucu de Jos), Felsőzsuk (Jucu de Sus), Kályán (Căianu).

-

69 DO: Kisesküllő (Aşchileu Mic), Esztény (Stoiana),Szentegyed (Sântejude); BSZ: Girolt (Ghirolt), Monostorszeg (Mănăşturel). In contrast, it appears that beyond the Meszes the p = 1/16 share was much more common (Diaconescu, Izvoare, 13, 15, 17, 19, 106, 189, 191).

-

70 If it were more documentable, we would probably find it in most parts of the Székely Land, too.

-

71 Szarkad (Sereca), Berény (Beriu), Kasztó (Căstău), Perkász (Pricaz). Cf. Müller, Landkapitel, 133; Müller, “Rechtslage der Rumänen,” 195, 235.

-

72 Szászárkos (near Balomir), Giesshübel (near Szászsebes [Sebeş/Mühlbach]), Fehéregyháza (near Szerdahely [Miercurea Sibiului/Reussmarkt]), Underten (between Alcina [Alţina/Alzen] and Kürpöd [Chirpăr/Kirchberg]). Cf. Jakó, Dézsma, 25; Müller, Landkapitel, 161.

-

73 Alkenyér (Şibot/Unterbrotsdorf), Felkenyér (Vinerea/Oberbrotsdorf), Cikendál (Ţichindeal/Ziegenthal), Glimboka (Glâmboaca/Hühnerbach), Hóföld (Fofeldea/Hochfeld), Illenbák (Ilimbav/Eulenbach), Szászaház (Săsăuş/Sachsenhausen), Kálbor (Calbor/Kaltbrunnen), Boholc (Boholţ/Buchholz), Sona (Şona/Schönau). Cf. Müller, “Rechtslage der Rumänen,” 192, 212, 217, 224–25, 234–37, 240.

-

74 FH: Poklos (Pâclişa), Sóspatak (Şeuşa), Táté (Totoi). Cf. Hegyi, “Románok tizedfizetése,” 28, 30–31; Hegyi, “Did Romanians,” 710 (note 73).

-

75 E.g. FH: Veresegyháza (Roşia de Secaş/Rothkirch), Meggykerék (Meşcreac); DO: Sajósebes (Ruştior/Niederschebesch), Solymos (Şoimuş/Almesch), Radla (Ragla/Radelsdorf), Alsóbalázsfalva (Blăjenii de Jos/Unterblasendorf), Fata (near Nagydemeter [Dumitra/Mettersdorf]). Cf. Jakó, Dézsma, 20, 23, 45, 47.

-

76 FH: Váralja (Orlat/Winsberg), Feketevíz (Săcel/Schwarzwasser), Alamor, Hosszútelke (Doştat/Thorstadt), Drassó, Dálya, Kútfalva, Birbó, Henningfalva (Henig). Cf. Hegyi, “Románok tizedfizetése,” 26–28, 30, 34.

-

77 1580: EOE, vol. 3, 149–51; Teutsch, Zehntrecht, 164–68; 1612: EOE, vol. 6, 254–55; Teutsch, Zehntrecht, 191–95. Cf. ibid., 55–67.

-

78 EOE, vol. 3, 244.

-

79 Teutsch, Zehntrecht, 185–86, 188–89. Cf. Müller, Landkapitel, 166.

-

80 E.g. 1664: Gudor, Gyulafehérvári Egyházmegye, 378 (Krakkó [Cricău/Krakau], FH), 406–7 (Alvinc [Vinţu de Jos/Winz], FH).

-

81 KÜ: Gálfalva (Găneşti), Pócsfalva (Păucişoara), Kissáros (Delenii), Kóródszentmárton (Coroisânmartin), Besenyő (Valea Izvoarelor), Mikefalva (Mica), Kápolna (Căpâlna de Sus), Héderfája (Idrifaia), Harangláb (Hărănglab), and probably also Szőkefalva (Seuca).

-

82 These findings are based on a comparison of the registers from 1563 and 1589 (SJAN-SB, F 3, 1-173, fol. 4r-v; Jakó, Dézsma, 34, 35, cf. Table 1, too).

-

83 Source of data: SJAN-SB, F 3, 1–173 (the values in brackets), Jakó, Dézsma, 20–71 (page numbers refer to this). Abbreviations: E = episcopal share of tithe, A= archdeaconal share of tithe, q = quarta, T = the whole tithe, P = priest’s share of tithe (for all these, the amount of the corresponding wage is indicated in florins), p = the rate of the priestly tithe. The first three are taken directly from the source, the others are calculated using the formulae: T = 4q; P = T – (E+A); p = P/T.

* The research on which this article is based was done with the financial support of the HTMKNP FAEK MTA National Program and of the K 145924 funding schemes of the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund of Hungary.